Proposals for a Jewish state

| Part of a series on | ||||||||||||||

| Jews and Judaism | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

There were several proposals for a Jewish state in the course of Jewish history between the destruction of ancient Israel and the founding of the modern State of Israel. While some of those have come into existence, others were never implemented. The Jewish national homeland usually refers to the State of Israel[1] or the Land of Israel,[2] depending on political and religious beliefs. Jews and their supporters, as well as their detractors and anti-Semites have put forth plans for Jewish states.

Andinia Plan

Andinia Plan (Spanish: plan Andinia) refers to both former ideas (dating to the 19th century) to establish a Jewish state in parts of Argentina and to an alleged contemporary plan. The 19th century plan stems from Theodore Herzl in his 1896 publication, Der Judenstaat, in which both Argentina and Palestine were proposed as potential sites for the Jewish homeland. The name and contents of the contemporary plan have wide currency in Argentine and Chilean extreme right-wing circles, but no evidence of its actual existence has ever been brought up, making it an example of a conspiracy theory.[3] Besides this, Argentina is home to one of the largest Jewish communities in the world.

Ararat city

In 1820, in a precursor to modern Zionism, Mordecai Manuel Noah tried to found a Jewish homeland at Grand Island in the Niagara River, to be called "Ararat," after Mount Ararat, the Biblical resting place of Noah's Ark. He erected a monument at the island which read "Ararat, a City of Refuge for the Jews, founded by Mordecai M. Noah in the Month of Tishri, 5586 (September, 1825) and in the Fiftieth Year of American Independence." Some have speculated whether Noah's utopian ideas may have influenced Joseph Smith, who founded the Latter Day Saint movement in Upstate New York a few years later. In his Discourse on the Restoration of the Jews Noah proclaimed his faith that the Jews would return and rebuild their ancient homeland. Noah called on America to take the lead in this endeavor.[4]

British Uganda Program

The British Uganda Program was a plan to give a portion of British East Africa to the Jewish people as a homeland.

The offer was first made by British Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain to Theodore Herzl's Zionist group in 1903. He offered 5,000 square miles (13,000 km2) of the Mau Plateau in what is today Kenya. The offer was a response to pogroms against the Jews in Russia, and it was hoped the area could be a refuge from persecution for the Jewish people.

The idea was brought to the World Zionist Organization's Zionist Congress at its sixth meeting in 1903 in Basel. There a fierce debate ensued. The African land was described as an "ante-chamber to the Holy Land", but other groups felt that accepting the offer would make it more difficult to establish a Jewish state in Palestine. Before the vote on the matter, the Russian delegation stormed out in opposition. In the end, the motion to consider the plan passed by 295 to 177 votes.

The next year, a three-man delegation was sent to inspect the plateau. Its high elevation gave it a temperate climate, making it suitable for European settlement. However, the observers found a dangerous land filled with lions and other creatures. Moreover, it was populated by a large number of Maasai who did not seem at all amenable to an influx of Europeans.

After receiving this report, the Congress decided in 1905 to politely decline the British offer. Some Jews, who viewed this as a mistake, formed the Jewish Territorialist Organization with the aim of establishing a Jewish state anywhere.[5]

Jewish Autonomous Oblast in USSR

On March 28, 1928, the Presidium of the General Executive Committee of the USSR passed the decree "On the attaching for Komzet of free territory near the Amur River in the Far East for settlement of the working Jews." The decree meant that there was "a possibility of establishment of a Jewish administrative territorial unit on the territory of the called region".[6]

On August 20, 1930, the General Executive Committee of the Russian Soviet Republic (RSFSR) accepted the decree "On formation of the Birobidzhan national region in the structure of the Far Eastern Territory". The State Planning Committee considered the Birobidzhan national region as a separate economic unit. In 1932, the first scheduled figures of the region development were considered and authorized.[6]

On May 7, 1934, the Presidium accepted the decree on its transformation in the Jewish Autonomous Region within the Russian Republic. In 1938, with formation of the Khabarovsk Territory, the Jewish Autonomous Region (JAR) was included in its structure.[6]

According to Joseph Stalin's national policy, each of the national groups that formed the Soviet Union would receive a territory in which to pursue cultural autonomy in a socialist framework. In that sense, it was also a response to two supposed threats to the Soviet state: Judaism, which ran counter to official state policy of atheism; and Zionism, the creation of the modern State of Israel, which countered Soviet views of nationalism. The idea was to create a new "Soviet Zion", where a proletarian Jewish culture could be developed. Yiddish, rather than Hebrew, would be the national language, and a new socialist literature and arts would replace religion as the primary expression of culture.

Stalin's theory on the National Question held that a group could only be a nation if it had a territory, and since there was no Jewish territory, per se, the Jews were not a nation and did not have national rights. Jewish Communists argued that the way to solve this ideological dilemma was to create a Jewish territory, hence the ideological motivation for the Jewish Autonomous Oblast. Politically, it was also considered desirable to create a Soviet Jewish homeland as an ideological alternative to Zionism and to the theory put forward by Socialist Zionists such as Ber Borochov that the Jewish Question could be resolved by creating a Jewish territory in Palestine. Thus Birobidzhan was important for propaganda purposes as an argument against Zionism which was a rival ideology to Marxism among left-wing Jews.

Another important goal of the Birobidzhan project was to increase settlement in the remote Soviet Far East, especially along the vulnerable border with China. In 1928, there was virtually no settlement in the area, while Jews had deep roots in the western half of the Soviet Union, in Ukraine, Belarus and Russia proper. In fact, there had initially been proposals to create a Jewish Soviet Republic in the Crimea or in part of Ukraine but these were rejected because of fears of antagonizing non-Jews in those regions.

The geography and climate of Birobidzhan were harsh, the landscape largely swampland, and any new settlers would have to build their lives from scratch. Some have even claimed that Stalin was also motivated by anti-Semitism in selecting Birobidzhan; that he wanted to keep the Jews as far away from the centers of power as possible,[7] even when Jews like Lazar Kaganovich occupied significant offices during that time and when Jews were promoted to important positions in Socialist countries of Eastern Europe. On the other hand, Ukrainians and Crimeans were reluctant to have a Jewish national home carved out of their territory, even though most Soviet Jews lived there, and there were very few alternative territories without rival national claims to them.

By the 1930s, a massive propaganda campaign was underway to induce more Jewish settlers to move there. Some methods used the standard Soviet propaganda tools of the era, and included posters and Yiddish-language novels describing a socialist utopia there. Other methods bordered on the bizarre. In one instance, leaflets promoting Birobidzhan were dropped from an airplane over a Jewish neighborhood in Belarus. In another instance, a government-produced Yiddish film called Seekers of Happiness told the story of a Jewish family that fled the Depression in the United States to make a new life for itself in Birobidzhan.

As the Jewish population grew, so did the impact of Yiddish culture on the region. A Yiddish newspaper, the Birobidzhaner Shtern ("Star of Birobidzhan"), was established; a theater troupe was created; and streets being built in the new city were named after prominent Yiddish authors such as Sholom Aleichem and Y. L. Peretz. The Yiddish language was deliberately bolstered as a basis for efforts to secularize the Jewish population and, despite the general curtailment of this action as described immediately below, the Birobidzhaner Shtern continues to publish a section in Yiddish.

The Birobidzhan experiment ground to a halt in the mid-1930s, during Stalin's first campaign of purges. Jewish leaders were arrested and executed, and Yiddish schools were shut down. Shortly after this, World War II brought to an abrupt end concerted efforts to bring Jews east.

There was a slight revival in the Birobidzhan idea after the war as a potential home for Jewish refugees. During that time, the Jewish population of the region peaked at almost one-third of the total. But efforts in this direction ended, with the Doctors' plot, the establishment of Israel as a Jewish state, and Stalin's second wave of purges shortly before his death. Again the Jewish leadership was arrested and efforts were made to stamp out Yiddish culture—even the Judaica collection in the local library was burned. In the ensuing years, the idea of an autonomous Jewish region in the Soviet Union was all but forgotten.

Some scholars, such as Louis Rapoport, Jonathan Brent and Vladimir Naumov, assert that Stalin had devised a plan to deport all of the Jews of the Soviet Union to Birobidzhan much as he had internally deported other national minorities such as the Crimean Tatars and Volga Germans, forcing them to move thousands of miles from their homes. The Doctors' Plot may have been the first element of this plan. If so, the plan was aborted by Stalin's death on March 5, 1953.

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union and new liberal emigration policies, most of the remaining Jewish population left for Germany and Israel. In 1991, the Jewish Autonomous Oblast was transferred from under the jurisdiction of Khabarovsk Krai to the jurisdiction of the Federation, but by then most of the Jews had left and the remaining Jews now constituted less than 2% of the local population. Nevertheless, Yiddish is again taught in the schools, a Yiddish radio station is in operation, and as noted above, the Birobidzhaner Shtern includes a section in Yiddish.

Fugu plan

Despite the little evidence to suggest that the Japanese had ever contemplated a Jewish state or a Jewish autonomous region,[8] Rabbi Marvin Tokayer and Mary Swartz published a book called The Fugu Plan in 1979. In this partly fictionalized book, Tokayer & Swartz gave the name the Fugu Plan or Fugu Plot (河豚計画 Fugu keikaku) to memoranda written in the 1930s Imperial Japan proposing settling Jewish refugees escaping Nazi-occupied Europe in Japanese territories. Tokayer and Swartz claim that the plan, which was viewed by its proponents as risky but potentially rewarding for Japan, was named after the Japanese word for puffer-fish, a delicacy which can be fatally poisonous if incorrectly prepared.[9]

Tokayer and Swartz base their claim on statements made by Captain Koreshige Inuzuka. They alleged that such a plan was first discussed in 1934 and then solidified in 1938, supported by notables such as Inuzuka, Ishiguro Shiro and Norihiro Yasue;[10] however, the signing of the Tripartite Pact in 1941 and other events prevented its full implementation. The memorandums were not called The Fugu Plan.

Ben-Ami Shillony, a professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, confirms that the statements upon which Tokayer and Swartz based their claim were taken out of context, and that the translation with which they worked was flawed. Shillony's view is further supported by Kiyoko Inuzuka.[11] In 'The Jews and the Japanese: The Successful Outsiders', he questioned whether the Japanese ever contemplated establishing a Jewish state or a Jewish autonomous region.[12][13][14]

Madagascar plan

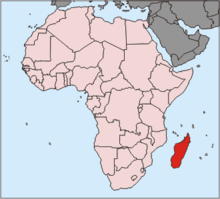

The Madagascar plan was a suggested policy of the Third Reich government of Nazi Germany to forcibly relocate the Jewish population of Europe to the island of Madagascar.[15]

Madagascar lies off the east coast of Africa |

The evacuation of European Jewry to the island of Madagascar was not a new concept. Henry Hamilton Beamish, Arnold Leese, Lord Moyne, German scholar Paul de Lagarde and the British, French, and Polish governments had all contemplated the idea.[15] Nazi Germany seized upon it, and in May 1940, in his Reflections on the Treatment of Peoples of Alien Races in the East, Heinrich Himmler declared: "I hope that the concept of Jews will be completely extinguished through the possibility of a large emigration of all Jews to Africa or some other colony."

Although some discussion of this plan had been brought forward from 1938 by other well-known Nazi ideologues, such as Julius Streicher, Hermann Göring, and Joachim von Ribbentrop, it was not until June 1940 that the plan was actually set in motion. As victory in France was imminent, it was clear that all French colonies would soon come under German control, and the Madagascar Plan could be realized. It was also felt that a potential peace treaty with Great Britain would put the British navy at Germany's disposal for use in the evacuation.

British Guiana

In March 1940, the issue of an alternative Jewish Homeland was raised and British Guiana (now Guyana) was discussed in this context. But the British Government decided that "the problem is at present too problematical to admit of the adoption of a definite policy and must be left for the decision of some future Government in years to come".[16]

Other attempts of Jewish self-governance throughout history

Ancient times

- Adiabene – an ancient kingdom in Mesopotamia with its capital at Arbil was ruled by Jewish converts during the first century.

- Anilai and Asinai – Babylonian-Jewish chieftains.

- Mahoza – During the beginning of sixth century Mar-Zutra II formed a politically independent state where he ruled from Mahoza for about 7 years.

- Nehardea – the seat of the exilarch in Babylonia.

- Khaybar – a self-governed oasis in Arabia.

- Himyar – there were many Jewish kings at this region of Yemen since 390 CE when a local chieftain named Tub'a Abu Kariba As'ad formed an Empire.

- Kingdom of Semien – a Jewish kingdom in Ethiopia

- Touat – a self-governed oasis in Algeria

Middle ages to 19th century

- The Resh Galuta or Exilarch exercised considerable authority over the Jewish community in the Persian Empire and later the Caliphate

- Khazar kingdom – during the Middle Ages Khazaria's official religion was Judaism. Jewish scholars and refugees were actively invited to settle within Khazar territory, particularly in Tmutarakan and the Crimea.

- Makhir of Narbonne and possibly his descendents were acknowledged by the Carolingian emperors as ethnarchs of western Jewry, with their seat at Narbonne

- Council of Four Lands – the central body of Jewish authority in Poland from 1580 to 1764. Seventy delegates from local kehillot met to discuss taxation and other issues important to the Jewish community. The "four lands" were Greater Poland, Little Poland, Ruthenia and Volhynia.

- Principality of Malabar from the eighth century to 1524 the Cochin Jews had an ethnarch ruling over them.

- The Mountain Jews of remote parts of Daghestan were self-ruling for much of the medieval and early modern period.

- Jarawa Berber tribe on the Maghreb in the seventh century, believed to be Jews, and resisted arabicization under the leadership of Queen Kahina.

- Jodensavanne: an attempt to establish a safe haven for Jews in Surinam

- Banou Israel: tribe of Jews of Bilad el-Sudan in Fati Lake Mali

Modern times

- In the early 20th century Cyprus and El Arish on the Sinai Peninsula in Egypt and its environs were proposed as a site for Jewish settlement by Herzl.

- Several proposals for a Jewish "republic" under Arab or Transjordanian suzerainty were put forward by the Hashemite kings of Hejaz and emirs of Transjordan; the closest these proposals came to fruition was the Faisal-Weizmann Agreement, which proved to be impossible to implement subsequent to the division of the Levant into League of Nations Mandates.

- Eastern Arabia A Russian Jewish doctor residing in France named Dr M L Rothstein proposed the establishment of a Jewish state in Al-Hasa modern day Saudi Arabia in September 1917.[17][18]

- Jewish Autonomous Oblast was a region created by the Soviet Union in the Russian Far East. It has been in existence from 1934 to the present.

- Salonika in the Ottoman Empire was populated mainly by Sephardim with Judeo-Spanish as the main language. After its incorporation to the Kingdom of Greece, it remained very Jewish until the arrival of Greek refugees from Anatolia in the 1920s.

- Albania – In 1935, British Zionist journalist Leo Elton traveled to Albania, apparently at his own initiative, to see if it would be possible to establish a Jewish national entity there. It seems the only surviving trace of his voyage is his report 10 years later to Hebrew University's first president, Judah Leib Magnes. The document rests in the Central Archive for the History of the Jewish People at the university's Givat Ram campus in Jerusalem. Elton's journey was spurred on by the increasing persecution of German Jews two years into the Nazi regime and Britain's refusal to increase the quotas on Jewish immigration to Mandatory Palestine. Elton writes that he first read of the idea in British newspapers reporting that the Albanian government welcomed Jewish immigration .

- The Kimberley Plan was a failed plan by the Freeland League, led by Isaac Nachman Steinberg, to resettle Jewish refugees from Europe in the Kimberley region in Australia before and during the Holocaust.[19]

- In 1941 Lord Moyne suggested to David Ben-Gurion that Jewish refugees could be resettled in East Prussia after Germany was defeated and the area's German inhabitants were expelled. Ben-Gurion responded that "the only way to get Jews to go [to East Prussia] would be with machine guns."[20]

- Kiryas Joel, New York – a town composed largely of Yiddish-speaking Hasidic Jews.

- Qırmızı Qəsəbə – The town is the primary settlement of Azerbaijan's population of Mountain Jews, who make up the population of approximately 4,000.

- Sitka, Alaska – a plan for Jews to settle the Sitka area in Alaska, the Slattery Report, was proposed by U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt's Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes in 1939 but turned down.:[21]

According to Ickes’s diaries, President Roosevelt wanted to move 10,000 settlers to Alaska each year for five years, but only 10 percent would be Jewish “to avoid the undoubted criticism” the program would receive if it brought too many Jews into the country. With Ickes’s support, Interior Undersecretary Harold Slattery wrote a formal proposal titled “The Problem of Alaskan Development,” which became known as the Slattery Report. It emphasized economic-development benefits rather than humanitarian relief: The Jewish refugees, Ickes reasoned, would “open up opportunities in the industrial and professional fields now closed to the Jews in Germany.”[22]

An alternate history of the proposal where Jews do settle in Sitka is the subject of author Michael Chabon's novel The Yiddish Policemen's Union.

- Vietnam – Vietnamese government officials in 2005, told Israeli officials of a plan discussed between Ho Chi Minh and Moshe Dayan to invite Jews to live in the country. No documentation of the offer and discussion has yet been made available. There is currently a small expatriate community of Jews in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, intermarrying with Vietnamese, with the first Bar Mitzvah in Vietnam held in 2004, in Hanoi.[23]

Proposals for a second Jewish state

Following the independence of the State of Israel, the goal of establishing a Jewish state was achieved. However, since then, there have been some proposals for a second Jewish state, in addition to Israel:

- Many Israeli settlers in the West Bank have mulled declaring independence as the State of Judea should Israel ever withdraw from the West Bank. The idea first surfaced following the PLO's declaration of a Palestinian state in 1988. Some settler activists feared that Israel would bow to international pressure and withdraw from the West Bank, and sought to lay the groundwork for a Halachic state in the West Bank should this come to pass. In January 1989, several hundred activists met and announced their intention to create such a state in the event of Israeli withdrawal.[24][25][26][27] The idea has been raised multiple times since.

- In May 2007, Israeli art student Ronen Eidelman, who was studying in Germany at the time, launched the "Medinat Weimar" movement, a political movement for the establishment of a second Jewish state in Thuringia, Germany, with Weimar as its capital.[28]

Anti-Zionist proposals for alternative Jewish homelands

As a prevailing strain of anti-Zionism puts forth an opposition to Israel's existence in the Middle East, a smaller wing of anti-Zionism focuses upon the circumstances of the resulting region-wide conflict which followed Israel's Jewish settlement and 1948 declaration of independence; this ideology proposes the hypothetical resettlement of the entire Jewish Israeli population in another isolated region of the world outside the Middle East.

Anti-Zionist proposals pre-1948

In 1902, Zionist Max Bodenheimer proposed the idea of the League of East European States, which would entail the establishment of a buffer state (Pufferstaat) within the Jewish Pale of Settlement of Russia, composed of the former Polish provinces annexed by Russia.[29][30]

In 1903, British Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain proposed the British Uganda Programme, and offered 5,000 square miles (13,000 km2) of the Mau Plateau in what is today Kenya and Uganda as a refuge from persecution for the Jewish people.

In 1938, leaders in Nazi Germany signed off on the Madagascar Plan, to evacuate all European Jews to the island of Madagascar.

Proposed deportation of Israelis to Central Europe

Prominent anti-Zionists including Azzam Tamimi and Helen Thomas have proposed sending the Jews in Israel to Europe or the United States.

In an English-language Palestinian-Israeli debate on Iranian TV, which aired on Press TV on January 14, 2008, Tamimi debated Israeli lecturer Yossi Mekelberg. In response to Mekelberg stating that "We need justice for everyone, and I will tell you where...", Tamimi stated that: "Justice? You go back to Germany. That's justice. You turn Germany into your state, not Palestine. Why should Palestine be a Jewish state? Why?"[31]

In January, 2006, Tamimi wrote that creation of the state of Israel "was a solution to a European problem and the Palestinians are under no obligation to be the scapegoats for Europe's failure to recognise the Jews as human beings entitled to inalienable rights. Hamas, like all Palestinians, refuses to be made to pay for the criminals who perpetrated the Holocaust. However, Israel is a reality and that is why Hamas is willing to deal with that reality in a manner that is compatible with its principles."[32]

The Middle East Media Research Institute (MEMRI) provided the following quotation from an article published by Tamimi in 1998: "If the Westerners as a whole – and the Germans in particular – are immersed in feelings of guilt because of what they have perpetrated against the Jews, isn't it a just thing that they will act together to expiate for their sins by granting the Jews a national homeland in central Europe, for instance, within one of the German states? Or, why will not the U.S., the Zionist father through adoption, grant [the Jews] one out of its more than fifty states..?"[33][34]

Helen Thomas, a Lebanese-American journalist and correspondent for United Press International, in 2010 after being asked by Rabbi David Nesenoff on camera for comments on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, suggested that Jews should "get the hell out of Palestine" and go back to Poland, Germany "And America and everywhere else. Why push people out of there who have lived there for centuries?".[35] The resulting uproar led to an initial apology and her resignation from UPI, but she defended her comments in other venues afterward.

Criticism

Such proposals to remove Jews from out of Israel/Palestine (or, at least, to claim another territory as a better homeland for the Jewish people than Israel) have been criticized as contradicting of both the corporate right to self-determination and indigenous land rights. Furthermore, suggestions or demands for Jewish people to move back to Central Europe are seen as implicitly targeting or minimizing the history of bigotry against Ashkenazi Jews in Central Europe (including, among other events, the Final Solution enacted by the German Nazi Party). Yoram Dori, an op-ed writer at The Jerusalem Post, reproached Helen Thomas for wanting to "exile us back to the inferno, as if nothing happened 65 years ago in Europe, as if our hands have not been stretched out for peace since the establishment of the state.[36]" Richard Cohen, op-ed writer for The Washington Post, described Thomas' comments as "revealing how very little she knew", citing post-WWII Polish violence against Polish Jews returning to their home villages from Displaced persons camps.[37] Finally, there are millions of Mizrahi Jews and Sephardi Jews that hail from countries other than the traditional Central European countries that the proposals believe Jews should go back to.

In his autobiographical novel A Tale of Love and Darkness, Israeli writer Amos Oz recounted his father's account of how the walls in Europe were covered in graffiti saying “Jews, go to Palestine," but when he reached Palestine, the walls were scrawled with the words “Jews, get out of Palestine.”[38]

See also

- Jewish homeland

- Proposals for a Palestinian state

- Territorialism

References

- ↑ The Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel

- ↑ The Land of Israel and Jerusalem have been embedded into Jewish national and religious consciousness since the 10th century BCE:

- "Israel was first forged into a unified nation from Jerusalem some three thousand years ago, when King David seized the crown and united the twelve tribes from this city... For a thousand years Jerusalem was the seat of Jewish sovereignty, the household site of kings, the location of its legislative councils and courts. In exile, the Jewish nation came to be identified with the city that had been the site of its ancient capital. Jews, wherever they were, prayed for its restoration." Roger Friedland, Richard D. Hecht. To Rule Jerusalem, University of California Press, 2000, p. 8. ISBN 0-520-22092-7

- "The centrality of Jerusalem to Judaism is so strong that even secular Jews express their devotion and attachment to the city and cannot conceive of a modern State of Israel without it... For Jews Jerusalem is sacred simply because it exists... Though Jerusalem's sacred character goes back three millennia...". Leslie J. Hoppe. The Holy City:Jerusalem in the theology of the Old Testament, Liturgical Press, 2000, p. 6. ISBN 0-8146-5081-3

- "Ever since King David made Jerusalem the capital of Israel 3,000 years ago, the city has played a central role in Jewish existence." Mitchell Geoffrey Bard, The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Middle East Conflict, Alpha Books, 2002, p. 330. ISBN 0-02-864410-7

- "For Jews the city has been the pre-eminent focus of their spiritual, cultural, and national life throughout three millennia." Yossi Feintuch, U.S. Policy on Jerusalem, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1987, p. 1. ISBN 0-313-25700-0

- "Jerusalem became the center of the Jewish people some 3,000 years ago" Moshe Maʻoz, Sari Nusseibeh, Jerusalem: Points of Friction – And Beyond, Brill Academic Publishers, 2000, p. 1. ISBN 90-411-8843-6

- "The Jewish people are inextricably bound to the city of Jerusalem. No other city has played such a dominant role in the history, politics, culture, religion, national life and consciousness of a people as has Jerusalem in the life of Jewry and Judaism. Since King David established the city as the capital of the Jewish state circa 1000 BCE, it has served as the symbol and most profound expression of the Jewish people's identity as a nation." Basic Facts you should know: Jerusalem, Anti-Defamation League, 2007. Accessed March 28, 2007.

- ↑ "ADL Outraged by Anti-Semitic Conspiracies Circulating in Connection with Tragic Fire in Chilean Patagonia". EDL. January 5, 2012. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- ↑ Selig Adler and Thomas E. Connolly. From Ararat to Suburbia: the History of the Jewish Community of Buffalo (Philadelphia: the Jewish Publication Society of America, 1960, Library of Congress Number 60-15834)

- ↑ Schreiber, Mordecai. The Shengold Jewish Encyclopedia, 2003. Page 291.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Establishment and Development of the JAR Jewish Autonomous Region official government website. Accessed 2007-08-30

- ↑ "Managing cultural, ethnic, religious and national identities in the Jewish autonomous region of post-Soviet Russia". University of Surrey. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- ↑ Politics and Culture in Wartime Japan by Ben-Ami Shillony. p 209

- ↑ Adam Gamble and Takesato Watanabe. A Public Betrayed: An Inside Look at Japanese Media Atrocities and Their Warnings to the West. Page 196-197.

- ↑ Shillony Ben-Ami. 'The Politics and Culture in Wartime Japan' page 170

- ↑ Inuzuka Kiyoko, Kaigun Inuzuka kikan no kiroku: Yudaya mondai to Nippon no kōsaku (Tokyo: Nihon kōgyō shimbunsha, 1982)

- ↑ Ben Ami-Shillony, The Jews and the Japanese: The Successful Outsiders (Rutland, VT: Tuttle, 1991)

- ↑ Origins of the Pacific War and the importance of 'Magic' by Keiichiro Komatsu, Palgrave Macmillan, 1999. ISBN 0-312-17385-7

- ↑ Politics and Culture in Wartime Japan by Ben-Ami Shillony. Edition: reprint, illustrated Published by Oxford University Press, 1991

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Browning, Christopher R. The Origins of the Final Solution. 2004. Page 81

- ↑ Zionist Movement And The Foundation Of Israel 1839–1972, The – Archive Editions

- ↑ Lowe, Daniel. "'The Jewish State of Eastern Arabia'". Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- ↑ Aderet, Ofer. "The proposal Balfour rejected: A Jewish state in the Persian Gulf". Haaretz.

- ↑ Steinberg, Isaac Nachman (1888–1957) by Beverley Hooper, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 16, Melbourne University Press, 2002, pp 298–299. Online Ed. published by Australian National University

- ↑ Hacohen, Dvora (1991). "Ben-Gurion and the Second World War: Plans for Mass Immigration to Palestine". In Jonathan Frankel. Jews and Messianism in the modern era: metaphor and meaning 7. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 255. ISBN 978-0-19-506690-6.

- ↑ "Novel involving Alaska Jewish colony is rooted in history," Tom Kizzia, Anchorage Daily News. http://www.adn.com/news/alaska/story/8828757p-8729539c.html

- ↑ Yerith Rosen (January–February 2012). "Alaska: That Great Big Jewish Land". Moment Magazine. Retrieved February 3, 2011.

- ↑ Reported by David Lempert, researcher in Vietnam, 1998–2006

- ↑ Kass, Ilana; O'Neill, Bard E (1997). The deadly embrace: the impact of Israeli and Palestinian rejectionism on the peace process. University Press of America. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-7618-0535-9.

- ↑ Ron, James (2003). Frontiers and ghettos: state violence in Serbia and Israel. University of California Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-520-23657-8.

- ↑ Rubinstein, Danny (22 January 2007). "The State of Judea". Haaretz.

- ↑ "Settlers seek new nation called Judea". Eugene Register-Guard. 17 January 1989. p. 3A.

- ↑ Graduate student pushes for Jewish state in Germany

- ↑ Michlic, Joanna Beata (2006). Poland's Threatening Other: The Image of the Jew from 1880 to the Present, pp. 48, 55–56. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-3240-3.

- ↑ Blobaum, Robert (2005). Anti-Semitism and Its Opponents in Modern Poland, p. 61. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-4347-4.

- ↑ "London-Based Hamas Palestinian Researcher 'Azzam Al-Tamimi: I Don't Give a Damn about a Palestinian State, or about the Jews Who Came to Israel from Europe (Clip no.1663)". Middle East Media Research Institute (MEMRI). January 14, 2008.

- ↑ Hamas will make a deal The Guardian January 30, 2006

- ↑ Institute of Islamic Political Thought, March 1998, Dr. 'Azzam Al-Tamimi, 'Reflection in Memory of the 50th Anniversary of the Ravishing of Palestine.'

- ↑ Adam Pashut (February 19, 2004). "Dr. 'Azzam Al-Tamimi: A Political-Ideological Brief (Inquiry and Analysis Series – No. 163)". Middle East Media Research Institute (MEMRI).

- ↑ "Helen Thomas Complete (original)". YouTube. Retrieved 2011-03-14.

- ↑ Yoram Dori (06-07-2010 <!- – 06:32 -->). "An open letter to Helen Thomas". The Jerusalem Post. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Richard Cohen (June 8, 2010). "What Helen Thomas missed". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Bronner, Ethan (6 March 2010). "Palestinian Sees Lesson Translating an Israeli’s Work". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

External links

- Albert Einstein on the Proposal to Create a Jewish Homeland in Peru, 1930 Shapell Manuscript Foundation