Propellant mass fraction

| Astrodynamics |

|---|

|

| Orbital mechanics |

|

Efficiency measures |

In aerospace engineering, the propellant mass fraction is the portion of a vehicle's mass which does not reach the destination, usually used as a measure of the vehicle's performance. In other words, the propellant mass fraction is the ratio between the propellant mass and the initial mass of the vehicle. In a spacecraft, the destination is usually an orbit, while for aircraft it is their landing location. A higher mass fraction represents less weight in a design. Another related measure is the payload fraction, which is the fraction of initial weight that is payload.

Formulation

The propellant mass fraction is given by:

And because,

it follows that:

Where:

is the propellant mass fraction

is the propellant mass fraction is the propellant mass

is the propellant mass is the initial mass of the vehicle

is the initial mass of the vehicle is the final mass of the vehicle

is the final mass of the vehicle

Significance

In rockets for a given target orbit, a rocket's mass fraction is the portion of the rocket's pre-launch mass (fully fueled) that does not reach orbit. The propellant mass fraction is the ratio of just the propellant to the entire mass of the vehicle at takeoff (propellant plus dry mass). In the cases of a single stage to orbit (SSTO) vehicle or suborbital vehicle, the mass fraction equals the propellant mass fraction; simply the fuel mass divided by the mass of the full spaceship. A rocket employing staging, which are the only designs to have reached orbit, has a mass fraction higher than the propellant mass fraction because parts of the rocket itself are dropped off en route. Propellant mass fractions are typically around 0.8 to 0.9.

In aircraft, mass fraction is related to range, an aircraft with a higher mass fraction can go farther. Aircraft mass fractions are typically around 0.5.

When applied to a rocket as a whole, a low mass fraction is desirable, since it indicates a greater capability for the rocket to deliver payload to orbit for a given amount of fuel. Conversely, when applied to a single stage, where the propellant mass fraction calculation doesn't include the payload, a higher propellant mass fraction corresponds to a more efficient design, since there is less non-propellant mass. Without the benefit of staging, SSTO designs are typically designed for mass fractions around 0.9. Staging increases the payload fraction, which is one of the reasons SSTO's appear difficult to build.

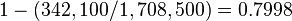

For example, the complete Space Shuttle system has:[1]

- fueled weight at liftoff: 1,708,500 kg

- dry weight at liftoff: 342,100 kg

Given these numbers, the propellant mass fraction is  .

.

The mass fraction plays an important role in the rocket equation:

Where  is the ratio of final mass to initial mass (i.e., one minus the mass fraction),

is the ratio of final mass to initial mass (i.e., one minus the mass fraction),  is the change in the vehicle's velocity as a result of the fuel burn and

is the change in the vehicle's velocity as a result of the fuel burn and  is the effective exhaust velocity (see below).

is the effective exhaust velocity (see below).

The term effective exhaust velocity is defined as:

where Isp is the fuel's specific impulse in seconds and gn is the standard acceleration of gravity (note that this is not the local acceleration of gravity).

To make a powered landing from orbit on a celestial body without an atmosphere requires the same mass reduction as reaching orbit from its surface, if the speed at which the surface is reached is zero.