Proof that π is irrational

| Part of a series of articles on the |

| mathematical constant π |

|---|

|

| Uses |

| Properties |

| Value |

| People |

| History |

| In culture |

| Related topics |

The number π (pi) has been studied since ancient times, and so has the concept of irrational numbers. An irrational number is any real number that cannot be expressed as a fraction a/b, where a is an integer and b is a non-zero integer.

It was not until the 18th century that Johann Heinrich Lambert proved that π is irrational. In the 19th century, Charles Hermite found a proof that requires no prerequisite knowledge beyond basic calculus. A simplification of Hermite's proof is due to Mary Cartwright. Two other such proofs are due to Ivan Niven and to Miklós Laczkovich.

In 1882, Ferdinand von Lindemann proved that π is not just irrational, but transcendental as well.[1]

Lambert's proof

In 1761, Lambert proved that π is irrational by first showing that this continued fraction expansion holds:

Then Lambert proved that if x is non-zero and rational then this expression must be irrational. Since tan(π/4) = 1, it follows that π/4 is irrational and therefore that π is irrational.[2] A simplification of Lambert's proof is given below. This result can also be proved using even more basic tools of calculus (integrals instead of series).[3][4]

Hermite's proof

This proof uses the characterization of π as the smallest positive number whose half is a zero of the cosine function and it actually proves that π2 is irrational.[5][6] As in many proofs of irrationality, the argument proceeds by reductio ad absurdum.

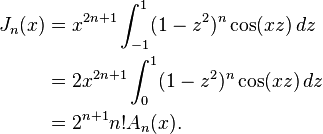

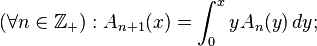

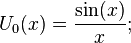

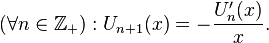

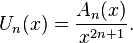

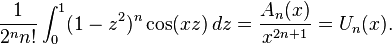

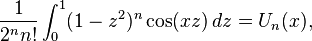

Consider the sequences (An)n ≥ 0 and (Un)n ≥ 0 of functions from R into R thus defined:

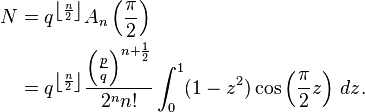

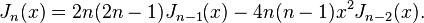

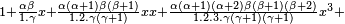

It can be proven by induction that

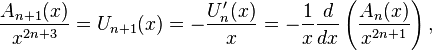

and that

and therefore that

So

which is equivalent to

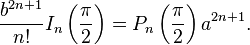

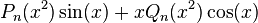

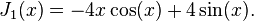

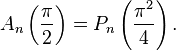

It follows by induction from this, together with the fact that A0(x) = sin(x) and that A1(x) = −x cos(x) + sin(x), that An(x) can be written as  , where Pn and Qn are polynomial functions with integer coefficients and where the degree of Pn is smaller than or equal to ⌊n⁄2⌋. In particular,

, where Pn and Qn are polynomial functions with integer coefficients and where the degree of Pn is smaller than or equal to ⌊n⁄2⌋. In particular,

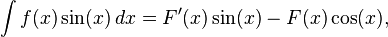

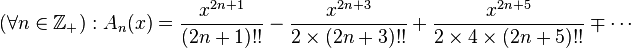

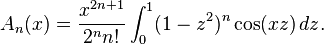

Hermite also gave a closed expression for the function  , namely

, namely

He did not justify this assertion, but it can be proved easily. First of all, this assertion is equivalent to

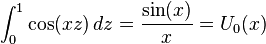

Proceeding by induction, take n = 0.

and, for the inductive step, consider any n ∈ Z+. If

then, using integration by parts and Leibniz's rule, one gets

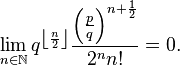

If π2/4 = p/q, with p and q in N, then, since the coefficients of Pn are integers and its degree is smaller than or equal to ⌊n⁄2⌋, q⌊n/2⌋Pn(π2/4) is some integer N. In other words,

But this number is clearly greater than 0; therefore, N ∈ N. On the other hand, the integral that appears here is not greater than 1 and

So, if n is large enough, N < 1. Thereby, a contradiction is reached.

Hermite did not present his proof as an end in itself but as an afterthought within his search for a proof of the transcendence of π. He discussed the differential-recurrent relations to motivate and to obtain the convenient integral representation. Once the integral is obtained, there are various ways to present a succinct and self-contained proof starting from the integral (as in Cartwright's or Niven's presentations), which Hermite could easily see (as he did in his proof of the transcendence of e[7]).

Moreover, Hermite's proof is closer to Lambert's proof than it seems. In fact, An(x) is the "residue" (or "remainder") of Lambert's continued fraction for tan(x).[4]

Cartwright's proof

Harold Jeffreys wrote that this proof was set as an example in an exam at Cambridge University in 1945 by Mary Cartwright, but that she had not traced its origin.[8]

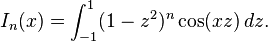

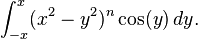

Consider the integrals

Two integrations by parts give the recurrence relation

If

then this becomes

Also

and

and

Hence for all n ∈ Z+,

where Pn(x) and Qn(x) are polynomials of degree ≤ 2n, and with integer coefficients (depending on n).

Take x = π⁄2, and suppose if possible that π⁄2 = b⁄a, where a and b are natural numbers (i.e., assume that π is rational). Then

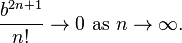

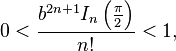

The right side is an integer. But 0 < In(π⁄2) < 2 since the interval [−1, 1] has length 2 and the function which is being integrated takes only values between 0 and 1. On the other hand,

Hence for sufficiently large n

that is, we could find an integer between 0 and 1. That is the contradiction that follows from the assumption that π is rational.

This proof is similar to Hermite's proof. Indeed,

However, it is clearly simpler. This is achieved bypassing the inductive definition of the functions An and taking as a starting point their expression as an integral.

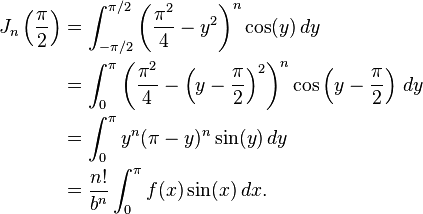

Niven's proof

This proof uses the characterization of π as the smallest positive zero of the sine function.[9]

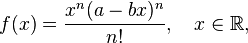

Preparation: Suppose that π is rational, i.e. π = a /b for some integers a and b ≠ 0, which may be taken without loss of generality to be positive. Given any positive integer n, we define the polynomial function

and denote by

the alternating sum of f and its first n even derivatives.

Claim 1: F(0) + F(π) is an integer.

Proof: Expanding f as a sum of monomials, the coefficient of xk is a number of the form ck /n! where ck is an integer, which is 0 if k < n. Therefore, f (k)(0) is 0 when k < n and it is equal to (k! /n!) ck if n ≤ k ≤ 2n; in each case, f (k)(0) is an integer and therefore F(0) is an integer.

On the other hand, f(π – x) = f(x) and so (–1)kf (k)(π – x) = f (k)(x) for each non-negative integer k. In particular, (–1)kf (k)(π) = f (k)(0). Therefore, f (k)(π) is also an integer and so F(π) is an integer (in fact, it is easy to see that F(π) = F(0), but that is not relevant to the proof). Since F(0) and F(π) are integers, so is their sum.

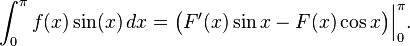

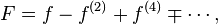

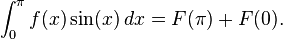

Claim 2:

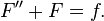

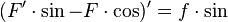

Proof: Since f (2n + 2) is the zero polynomial, we have

The derivatives of the sine and cosine function are given by sin' = cos and cos' = −sin. Hence the product rule implies

By the fundamental theorem of calculus

Since sin 0 = sin π = 0 and cos 0 = – cos π = 1 (here we use the above mentioned characterization of π as a zero of the sine function), Claim 2 follows.

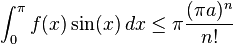

Conclusion: Since f(x) > 0 and sin x > 0 for 0 < x < π (because π is the smallest positive zero of the sine function), Claims 1 and 2 show that F(0) + F(π) is a positive integer. Since 0 ≤ x(a – bx) ≤ πa and 0 ≤ sin x ≤ 1 for 0 ≤ x ≤ π, we have, by the original definition of f,

which is smaller than 1 for large n, hence F(0) + F(π) < 1 for these n, by Claim 2. This is impossible for the positive integer F(0) + F(π).

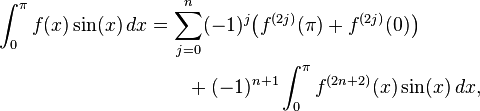

The above proof is a polished version, which is kept as simple as possible concerning the prerequisites, of an analysis of the formula

which is obtained by 2n + 2 integrations by parts. Claim 2 essentially establishes this formula, where the use of F hides the iterated integration by parts. The last integral vanishes because f (2n + 2) is the zero polynomial. Claim 1 shows that the remaining sum is an integer.

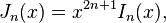

Niven's proof is closer to Cartwright's (and therefore Hermite's) proof than it appears at first sight.[4] In fact,

Therefore, the substitution xz = y turns this integral into

In particular,

Another connection between the proofs lies in the fact that Hermite already mentions[5] that if f is a polynomial function and

then

from which it follows that

Laczkovich's proof

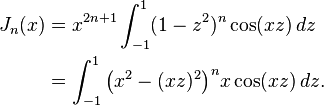

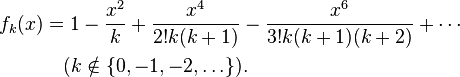

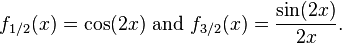

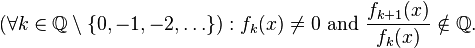

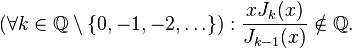

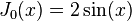

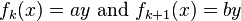

Miklós Laczkovich's proof is a simplification of Lambert's original proof.[10] He considers the functions

These functions are clearly defined for all x ∈ R. Besides

Claim 1: The following recurrence relation holds:

Proof: This can be proved by comparing the coefficients of the powers of x.

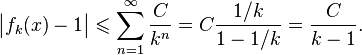

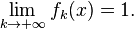

Claim 2: For each x ∈ R,

Proof: In fact, the sequence x2n/n! is bounded (since it converges to 0) and if C is an upper bound and if k > 1, then

Claim 3: If x ≠ 0 and if x2 is rational, then

Proof: Otherwise, there would be a number y ≠ 0 and integers a and b such that  . In order to see why, take y = fk + 1(x), a = 0 and b = 1 if fk(x) = 0; otherwise, choose integers a and b such that fk + 1(x)/fk(x) = b/a and define y = fk(x)/a = fk + 1(x)/b. In each case, y cannot be 0, because otherwise it would follow from claim 1 that each fk + n(x) (n ∈ N) would be 0, which would contradict claim 2. Now, take a natural number c such that all three numbers bc/k, ck/x2 and c/x2 are integers and consider the sequence

. In order to see why, take y = fk + 1(x), a = 0 and b = 1 if fk(x) = 0; otherwise, choose integers a and b such that fk + 1(x)/fk(x) = b/a and define y = fk(x)/a = fk + 1(x)/b. In each case, y cannot be 0, because otherwise it would follow from claim 1 that each fk + n(x) (n ∈ N) would be 0, which would contradict claim 2. Now, take a natural number c such that all three numbers bc/k, ck/x2 and c/x2 are integers and consider the sequence

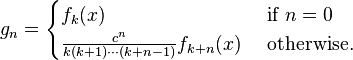

Then

On the other hand, it follows from claim 1 that

which is a linear combination of  and

and  with integer coefficients. Therefore, each

with integer coefficients. Therefore, each  is an integer multiple of y. Besides, it follows from claim 2 that each

is an integer multiple of y. Besides, it follows from claim 2 that each  (and therefore that gn ≥

(and therefore that gn ≥  ) if n is large enough and that the sequence of all

) if n is large enough and that the sequence of all  's converges to 0. But a sequence of numbers greater than or equal to

's converges to 0. But a sequence of numbers greater than or equal to  cannot converge to 0.

cannot converge to 0.

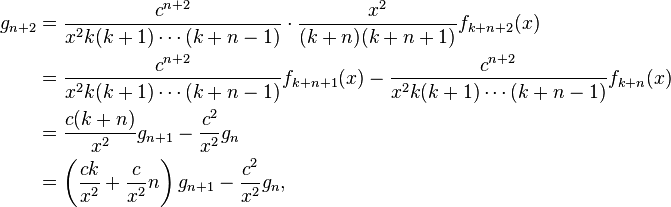

Since f1/2(π⁄4) = cos(π⁄2) = 0, it follows from claim 3 that π2/16 is irrational and therefore π is irrational.

On the other hand, since

another consequence of claim 3 is that, if x ∈ Q\{0}, then tan x is irrational.

Laczkovich's proof is really about the hypergeometric function. In fact, fk(x) = 0F1(k; −x2) and Gauss found a continued fraction expansion of the hypergeometric function using its functional equation.[11] This allowed Laczkovich to find a new and simpler proof of the fact that the tangent function has the continued fraction expansion that Lambert had discovered.

Laczkovich's result can also be expressed in Bessel functions of the first kind  . In fact, Γ(k)Jk − 1(2x) = xk − 1fk(x). So Laczkovich's result is equivalent to: If x ≠ 0 and if x2 is rational, then

. In fact, Γ(k)Jk − 1(2x) = xk − 1fk(x). So Laczkovich's result is equivalent to: If x ≠ 0 and if x2 is rational, then

See also

- Proof that e is irrational

- Proof that π is transcendental

- A short proof from Bourbaki

References

- ↑ Lindemann, Ferdinand von (2004) [1882], "Ueber die Zahl π", in Berggren, Lennart; Borwein, Jonathan M.; Borwein, Peter B., Pi, a source book (3rd ed.), New York: Springer-Verlag, pp. 194–225, ISBN 0-387-20571-3

- ↑ Lambert, Johann Heinrich (2004) [1768], "Mémoire sur quelques propriétés remarquables des quantités transcendantes circulaires et logarithmiques", in Berggren, Lennart; Borwein, Jonathan M.; Borwein, Peter B., Pi, a source book (3rd ed.), New York: Springer-Verlag, pp. 129–140, ISBN 0-387-20571-3

- ↑ Zhou, Li; Markov, Lubomir (2010), "Recurrent Proofs of the Irrationality of Certain Trigonometric Values", American Mathematical Monthly 117 (4): 360–362, arXiv:0911.1933, doi:10.4169/000298910x480838

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Zhou, Li (2011), "Irrationality proofs a la Hermite", Math. Gazette (November), arXiv:0911.1929

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Hermite, Charles (1873), "Extrait d'une lettre de Monsieur Ch. Hermite à Monsieur Paul Gordan", Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik (in French) 76: 303–311

- ↑ Hermite, Charles (1873), "Extrait d'une lettre de Mr. Ch. Hermite à Mr. Carl Borchardt", Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik (in French) 76: 342–344

- ↑ Hermite, Charles (1912) [1873], "Sur la fonction exponentielle", in Picard, Émile, Œuvres de Charles Hermite (in French) III, Gauthier-Villars, pp. 150–181

- ↑ Jeffreys, Harold (1973), Scientific Inference (3rd ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 268, ISBN 0-521-08446-6

- ↑ Niven, Ivan (1947), "A simple proof that π is irrational" (PDF), Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 53 (6): 509

- ↑ Laczkovich, Miklós (1997), "On Lambert's proof of the irrationality of π", American Mathematical Monthly 104 (5): 439–443, JSTOR 2974737

- ↑ Gauss, Carl Friedrich (1811–1813), "Disquisitiones generales circa seriem infinitam

etc", Commentationes Societatis Regiae Scientiarum Gottingensis recentiores (in Latin) 2

etc", Commentationes Societatis Regiae Scientiarum Gottingensis recentiores (in Latin) 2

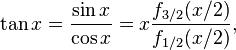

![\begin{align}

& {}\quad \frac{1}{2^{n+1}(n+1)!}\int_0^1(1-z^2)^{n+1}\cos(xz)\,dz \\

& =\frac{1}{2^{n+1}(n+1)!}\Biggl(\overbrace{\left.(1-z^2)^{n+1}\frac{\sin(xz)}x\right|_{z=0}^{z=1}}^{=\,0} + \int_0^12(n+1)(1-z^2)^nz\frac{\sin(xz)}x\,dz\Biggr)\\[8pt]

&=\frac1x\cdot\frac1{2^nn!}\int_0^1(1-z^2)^nz\sin(xz)\,dz\\[8pt]

&=-\frac1x\cdot\frac d{dx}\left(\frac1{2^nn!}\int_0^1(1-z^2)^n\cos(xz)\,dz\right) \\[8pt]

& =-\frac{U_n'(x)}x = U_{n+1}(x).

\end{align}](../I/m/b8a2cec1bcc886897734481fec6a5bba.png)