Probabilistic automaton

In mathematics and computer science, the probabilistic automaton (PA) is a generalization of the non-deterministic finite automaton; it includes the probability of a given transition into the transition function, turning it into a transition matrix or stochastic matrix. Thus, the probabilistic automaton generalizes the concept of a Markov chain or subshift of finite type. The languages recognized by probabilistic automata are called stochastic languages; these include the regular languages as a subset. The number of stochastic languages is uncountable.

The concept was introduced by Michael O. Rabin in 1963;[1] a certain special case is sometimes known as the Rabin automaton. In recent years, a variant has been formulated in terms of quantum probabilities, the quantum finite automaton.

Definition

The probabilistic automaton may be defined as an extension of a non-deterministic finite automaton  , together with two probabilities: the probability

, together with two probabilities: the probability  of a particular state transition taking place, and with the initial state

of a particular state transition taking place, and with the initial state  replaced by a stochastic vector giving the probability of the automaton being in a given initial state.

replaced by a stochastic vector giving the probability of the automaton being in a given initial state.

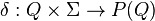

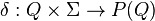

For the ordinary non-deterministic finite automaton, one has

- a finite set of states

- a finite set of input symbols

- a transition function

- a set of states

distinguished as accepting (or final) states

distinguished as accepting (or final) states  .

.

Here,  denotes the power set of

denotes the power set of  .

.

By use of currying, the transition function  of a non-deterministic finite automaton can be written as a membership function

of a non-deterministic finite automaton can be written as a membership function

so that  if

if  and

and  if

if  . The curried transition function can be understood to be a matrix with matrix entries

. The curried transition function can be understood to be a matrix with matrix entries

The matrix  is then a square matrix, whose entries are zero or one, indicating whether a transition

is then a square matrix, whose entries are zero or one, indicating whether a transition  is allowed by the NFA. Such a transition matrix is always defined for a non-deterministic finite automaton.

is allowed by the NFA. Such a transition matrix is always defined for a non-deterministic finite automaton.

The probabilistic automaton replaces this matrix by a stochastic matrix  , so that the probability of a transition is given by

, so that the probability of a transition is given by

A state change from some state to any state must occur with probability one, of course, and so one must have

for all input letters  and internal states

and internal states  . The initial state of a probabilistic automaton is given by a row vector

. The initial state of a probabilistic automaton is given by a row vector  , whose components add to unity:

, whose components add to unity:

The transition matrix acts on the right, so that the state of the probabilistic automaton, after consuming the input string  , would be

, would be

In particular, the state of a probabilistic automaton is always a stochastic vector, since the product of any two stochastic matrices is a stochastic matrix, and the product of a stochastic vector and a stochastic matrix is again a stochastic vector. This vector is sometimes called the distribution of states, emphasizing that it is a discrete probability distribution.

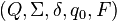

Formally, the definition of a probabilistic automaton does not require the mechanics of the non-deterministic automaton, which may be dispensed with. Formally, a probabilistic automaton PA is defined as the tuple  . A Rabin automaton is one for which the initial distribution

. A Rabin automaton is one for which the initial distribution  is a coordinate vector; that is, has zero for all but one entries, and the remaining entry being one.

is a coordinate vector; that is, has zero for all but one entries, and the remaining entry being one.

Stochastic languages

The set of languages recognized by probabilistic automata are called stochastic languages. They include the regular languages as a subset.

Let  be the set of "accepting" or "final" states of the automaton. By abuse of notation,

be the set of "accepting" or "final" states of the automaton. By abuse of notation,  can also be understood to be the column vector that is the membership function for

can also be understood to be the column vector that is the membership function for  ; that is, it has a 1 at the places corresponding to elements in

; that is, it has a 1 at the places corresponding to elements in  , and a zero otherwise. This vector may be contracted with the internal state probability, to form a scalar. The language recognized by a specific automaton is then defined as

, and a zero otherwise. This vector may be contracted with the internal state probability, to form a scalar. The language recognized by a specific automaton is then defined as

where  is the set of all strings in the alphabet

is the set of all strings in the alphabet  (so that * is the Kleene star). The language depends on the value of the cut-point

(so that * is the Kleene star). The language depends on the value of the cut-point  , normally taken to be in the range

, normally taken to be in the range  .

.

A language is called η-stochastic if and only if there exists some PA that recognizes the language, for fixed  . A language is called stochastic if and only if there is some

. A language is called stochastic if and only if there is some  for which

for which  is η-stochastic.

is η-stochastic.

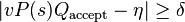

A cut-point is said to be an isolated cut-point if and only if there exists a  such that

such that

for all

Properties

Every regular language is stochastic, and more strongly, every regular language is η-stochastic. A weak converse is that every 0-stochastic language is regular; however, the general converse does not hold: there are stochastic languages that are not regular.

Every η-stochastic language is stochastic, for some  .

.

Every stochastic language is representable by a Rabin automaton.

If  is an isolated cut-point, then

is an isolated cut-point, then  is a regular language.

is a regular language.

p-adic languages

The p-adic languages provide an example of a stochastic language that is not regular, and also show that the number of stochastic languages is uncountable. A p-adic language is defined as the set of strings in the letters  such that

such that

That is, a p-adic language is merely the set of real numbers, written in base-p, such that they are greater than  . It is straightforward to show that all p-adic languages are stochastic. However, a p-adic language is regular if and only if

. It is straightforward to show that all p-adic languages are stochastic. However, a p-adic language is regular if and only if  is rational. In particular, this implies that the number of stochastic languages is uncountable.

is rational. In particular, this implies that the number of stochastic languages is uncountable.

Generalizations

The probabilistic automaton has a geometric interpretation: the state vector can be understood to be a point that lives on the face of the standard simplex, opposite to the orthogonal corner. The transition matrices form a monoid, acting on the point. This may be generalized by having the point be from some general topological space, while the transition matrices are chosen from a collection of operators acting on the topological space, thus forming a semiautomaton. When the cut-point is suitably generalized, one has a topological automaton.

An example of such a generalization is the quantum finite automaton; here, the automaton state is represented by a point in complex projective space, while the transition matrices are a fixed set chosen from the unitary group. The cut-point is understood as a limit on the maximum value of the quantum angle.

References

- ↑ Michael O. Rabin (1963). "Probabilistic Automata". Information and Control 6 (3): 230–245. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- Arto Salomaa, Theory of Automata (1969) Pergamon Press, Oxford (See chapter 2).

![\left[\theta_a\right]_{qq^\prime}=\delta(q,a,q^\prime)](../I/m/d045444687ba4a28f85c9f962f4f27e6.png)

![\left[P_a\right]_{qq^\prime}](../I/m/347be564fd357cdb7d5dfc9dc5c04108.png)

![\sum_{q^\prime}\left[P_a\right]_{qq^\prime}=1](../I/m/29993e12567a6afab4c03477340ce793.png)

![\sum_{q}\left[v\right]_{q}=1](../I/m/468a918bc80ff5cbe446228c4cb13a59.png)