Principality of Catalonia

| Principality of Catalonia | |||||

| Principat de Catalunya (Catalan) | |||||

| Principality of the Crown of Aragon (1162-1641, 1652-1714) Principality of the Monarchy of Spain (1516-1641, 1652-1714) Principality of the Kingdom of France (1641-1652) | |||||

| |||||

Territory of the Principality of Catalonia until 1659. | |||||

| Capital | Barcelona | ||||

| Languages | Catalan, Latin | ||||

| Religion | Catholic | ||||

| Government | Limited monarchy | ||||

| King | |||||

| - | 1162–1196 | Alfons I (first) | |||

| - | 1706–1714 | Charles III (last) | |||

| President of the Generalitat | |||||

| - | 1359–1562 | Berenguer de Cruïlles (first) | |||

| - | 1713–1714 | Josep de Vilamala (last) | |||

| Legislature | General Court of Catalonia | ||||

| Historical era | Medieval / Early Modern | ||||

| - | Marriage of Ramon Berenguer IV and Petronila | 1137 | |||

| - | Reign of Alfons I | 1162 | |||

| - | First Catalan Courts | 1283 | |||

| - | Reign of Charles V | 1516 | |||

| - | Catalan Revolt | 1640-1652 | |||

| - | Treaty of the Pyrenees | 1659 | |||

| - | War of Spanish Succession | 1701- 1714 | |||

| Currency | Croat, Lliura barcelonina | ||||

| Today part of | | ||||

The Principality of Catalonia (Catalan: Principat de Catalunya, Occitan: Principautat de Catalonha, Latin: Principatus Cathaloniæ), is a historic territory in the northeastern Iberian Peninsula, mostly in Spain and with an adjoining portion in southern France.

The first reference to Catalonia and the Catalans appears in the Liber maiolichinus de gestis Pisanorum illustribus, a Pisan chronicle (written between 1117 and 1125) of the conquest of Minorca by a joint force of Italians, Catalans, and Occitans. At the time, Catalonia did not yet exist as a political entity, though the use of this term seems to acknowledge Catalonia as a cultural or geographical entity.

The counties that would eventually make up the Principality of Catalonia were gradually unified under the rule of the Count of Barcelona. In 1137, both the County of Barcelona and the Kingdom of Aragon were unified dinastically, creating the Crown of Aragon, but Aragon and Catalonia retained their own political structure and legal traditions. Because of these legal differences and their use of different language —Aragonese and Catalan— an official recognition of the Catalan Counties as a distinct political entity became necessary.

Under Alfons the Troubador, Catalonia was first used legally.[1] Still, the term Principality of Catalonia was not used legally until the 14th century, when it was applied to the territories ruled by the Court of Catalonia.

The term "Principality of Catalonia" remained in use until the Second Spanish Republic, when its use declined because of its historical relation to the monarchy. Today, the term is used primarily by Catalan nationalists and independentists to refer collectively to the French and Spanish-administered parts of Catalonia.

History of Catalonia

Like much of the Mediterranean coast of the Iberian Peninsula, it was colonized by Ancient Greeks, which chose Roses to settle in. Both Greeks and Carthaginians interacted with the main Iberian population. After the Carthaginian defeat, it became, along with the rest of Hispania, a part of the Roman Empire, Tarraco being one of the main Roman posts in the Iberian Peninsula.

The Visigoths ruled briefly after the Roman Empire's collapse, but Moorish Al-Andalus gained control in the 8th century. After the defeat of Emir Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqiwas's troops at Tours in 732, the Franks conquered the former Visigoth territories which had been captured by the Muslims or had become allied with them, in what today is the northernmost part of Catalonia. In 795, Charlemagne created what came to be known as the Marca Hispanica, a buffer zone beyond the province of Septimania made up of locally administered separate petty kingdoms which served as a defensive barrier between the Umayyad Moors of Al-Andalus and the Frankish Kingdom.

Distinctive Catalan culture started to develop in the Middle Ages stemming from a number of these petty kingdoms organized as small counties throughout the northernmost part of Catalonia. The counts of Barcelona were Frankish vassals nominated by the Carolingian emperor then the king of the Franks, to whom they were feudatories (801-987).

In 987 the count of Barcelona did not recognise Frankish king Hugh Capet and his new dynasty which put it effectively out of the Frankish rule. Then, in 1137 Ramon Berenguer IV, Count of Barcelona married Petronilla of Aragon establishing the dynastic union of the County of Barcelona and its dominions with the Kingdom of Aragon which was to create the Crown of Aragon.

It was not until 1258, by the Treaty of Corbeil, that the king of France as heir of Charlemagne and the ancient Frankish Empire did formally relinquish his feudal overlordship over the counties of the Principality of Catalonia to the king of Aragon James I, descendant of Ramon Berenguer IV and heir of the House of Barcelona. This Treaty turned the de facto independence into a full de jure recognition of the Catalan counties as constituent members of the Crown of Aragon, whereas the king of Aragon and count of Barcelona also relinquished any claim over territories in southern France (except the counties of the Roussillon-Vallespir, Capcir and Conflent that were and remained part of the geographical area known as Catalonie or Cathalania). The treaty solved a historical incongruence, as the counties had been ruled independently for more than two centuries. As a coastal territory within the Crown of Aragon and the increasing importance of the port of Barcelona, Catalonia became the centre of the Crown's maritime power, helping to expand its influence and power by conquest and trade into Valencia, the Balearic Islands, Sardinia and Sicily.

Catalan Constitutions (1283)

The first Catalan Constitutions are of the ones from the Corts of Barcelona from 1283. The last ones were promulgated by the court of 1702. The compilations of the constitutions and other rights of Catalonia followed the Roman tradition of the Codex. The Parliament of Catalonia, dating from the 11th century, is one of the first parliaments in continental Europe.

Catalonia after the Middle Ages

The marriage of Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon (1469) unified two of the three major Christian kingdoms in the Iberian peninsula, while the Kingdom of Navarre was incorporated later following Ferdinand II's 1512 invasion of the Basque kingdom. This resulted in the reinforcement of the concept of Spain, which was already present in the mind of the these kings,[2] made up by the former Crown of Aragon, Castile, and a Navarre annexed to Castile (1515). In 1492, the last remaining portion of Al-Andalus around Granada was conquered and the Spanish conquest of the Americas began. Political power began to shift away from Aragon toward Castile and, subsequently, from Castile to the Spanish Empire, which engaged in frequent warfare in Europe striving for world domination.

For an extended period, Catalonia, as part of the late Crown of Aragon, continued to retain its own laws and constitutions but these gradually eroded in the course of the transition from a feudal territory to a modern one and the king's struggle to get from the territories as much of the power as possible until they were finally suppressed as a result of the War of the Spanish Succession defeat. Over the next few centuries, Catalonia was generally on the losing side of a series of wars that led steadily to more centralization of power in Spain.

In 1659, after the Treaty of the Pyrenees signed by Philip IV of Spain, the comarques (counties) of Roussillon, Conflent, Vallespir and part of la Cerdanya, now known as French Cerdagne were ceded to France. In recent times, this area has come to be known in Catalonia, as Northern Catalonia (Roussillon in French).

Catalan institutions were suppressed in this part of the territory and public use of Catalan language was prohibited. Currently, this region is administratively part of French Départment of Pyrénées-Orientales.

At the end of the War of the Spanish Succession (in which the Catalans supported the unsuccessful claim of the Archduke Charles of Austria) the victorious Bourbon Duke of Anjou, now Philip V, signed the Nueva Planta decrees, which abolished the Crown of Aragon and all remaining Catalan institutions and prohibited the administrative use of Catalan language.

So late as in the 18th and 19th centuries, Spanish Catalonia benefited from the beginning of open commerce to America and protectionist policies enacted by the Spanish government, becoming a center of Spain's industrialization; to this day it remains one of the most industrialized parts of Spain, along with Madrid and the Basque Country. On several occasions during the first third of the 20th century, Spanish Catalonia gained and lost varying degrees of autonomy, but as in most regions of Spain, Catalan autonomy and culture were crushed to an unprecedented degree after the defeat of the Second Spanish Republic (founded 1931) in the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) which brought Francisco Franco to power. Public use of the Catalan language was again banned after a brief period of general recuperation.

The Franco era ended with Franco's death in 1975; in the subsequent Spanish transition to democracy, Catalonia recovered political and cultural autonomy. It became one of the autonomous communities of Spain. In comparison, "Northern Catalonia" in France has no autonomy.

The term Principality

The counts of Barcelona were commonly considered the princeps or primus inter pares ("the first among equals") by the other counts of the Spanish March, both because of their military and economic power, and the supremacy of Barcelona over other cities.

Thus, the count of Barcelona, Ramon Berenguer I, is called "Prince of Barcelona, Count of Gerona and Marchis of Ausona" (princeps Barchinonensis, comes Gerundensis, marchio Ausonensis) in the Act of Consecration of the Cathedral of Barcelona (1058). There are also several references to the Prince in different sections of the Usages of Barcelona, the collection of laws that ruled the county since the early 11th century. Usage #64 calls principatus the group of counties of Barcelona, Gerona, and Ausona, all of them under the authority of the count of Barcelona.[3]

The first reference to the Principatus Cathaloniae is found in the convocation of Courts in Perpignan in 1350, presided by the king Peter IV of Aragon and III of Barcelona. It was intended to indicate that the territory under the laws produced by those Courts was not a kingdom, but the enlargement of the territory under the authority of the Count of Barcelona, who was also the king of Aragon, as seen in the "Actas de las cortes generales de la Corona de Aragón 1362-1363".[4] However, there seems to be an older reference, in a more informal context, in Ramon Muntaner's chronicles.

As the Count of Barcelona and the Courts added more counties under his jurisdiction, such as the County of Urgell, the name of "Catalonia", which comprised several counties of different names including the County of Barcelona, was used for the whole. The terms Catalonia and catalans were commonly used to refer to the territory in Northeastern Spain and western Mediterranean France, as well as its inhabitants, and not just the county of Barcelona, at least since the beginnings of the 12th century, as shown in the earliest recordings of these names in the Liber Maiolichinus (around 1117-1125).

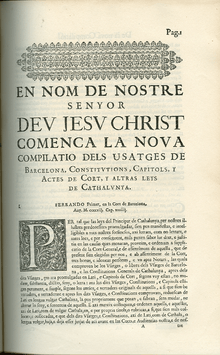

The term Principatus Cathaloniae or simply Principatus never achieved official status as the various covers of Catalan constitutions prove,[5][6] until Philip V of Spain used it to describe the Catalan territories in the Nueva Planta decrees.[7] In 1931, Republican movements favoured its abandonment because it is historically related to the monarchy.

Neither the Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia, Spanish Constitution nor French Constitution, mention this denomination, but, despite most of them being republican, it is moderately popular among Catalan nationalists and independentists.

Language

Catalonia constitutes the original nucleus where Catalan is spoken. The Catalan language shares common traits with the Romance languages of Iberia and Gallo-Romance languages of southern France, it is regarded by some linguists as being an Ibero-Romance language (the group that includes Spanish), and by a majority as a Gallo-Romance language, such as French or Occitan from which Catalan diverged between 11th and 14th centuries.[8]

Catalan is one of the three official languages of autonomous community of Catalonia, as stated in the Catalan Statute of Autonomy; the other two are Spanish, and Occitan in its Aranese variety. Catalan has not official recognition in "Northern Catalonia".

Catalan has official status alongside Spanish in the Balearic Islands and in the Land of Valencia (where it is called Valencian), as well as Algherese Catalan alongside Italian in the city of Alghero.

Culture

- Traditions of Catalonia

- Category:Catalan culture

- Category:Catalan literature

- Category:Catalan art

See also

- Catalan constitutions, from 1283

- Catalan Countries

- Cuisine of Catalonia

- Famous Catalan people

- Catalan nationalism

- Generalitat de Catalunya

References

- ↑ Sesma Muñoz, José Angel. La Corona de Aragón. Una introducción crítica. Zaragoza: Caja de la Inmaculada, 2000 (Colección Mariano de Pano y Ruata - Dir. Guillermo Fatás Cabeza). ISBN 84-95306-80-8.

- ↑ José Manuel Nieto Soria (2007). "Conceptos de España en tiempos de los Reyes Catolicos". Norba. Nueva Revista de Historia (Universidad de Extremadura) 19: 105–123. ISSN 0213-375X.

- ↑ See Fita Colomé, Fidel, El principado de Cataluña. Razón de este nombre., Boletín de la Real Academia de la Historia, Vol. 40 (1902), p. 261. (In Spanish)

- ↑ BITECA Manid 2045: Barcelona: Arxiu Corona Aragó, vol. 948

- ↑ Image:Usatges.png

- ↑ Image:ConstCATMonso1535.png

- ↑ Image:DecretNovaPlanta.png

- ↑ Riquer, Martí de, Història de la Literatura Catalana, vol. 1. Barcelona: Edicions Ariel, 1964

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||