Prince étranger

Prince étranger (English: foreign prince) was a high, though somewhat ambiguous, rank at the French royal court of the ancien régime.

Terminology

In medieval Europe, a nobleman bore the title of prince as an indication of sovereignty, either actual or potential. Aside from those who were or claimed to be monarchs, it belonged to those who were in line to succeed to a royal or independent throne.[1] France had several categories of prince in the post-medieval era. They frequently quarrelled, and sometimes sued each other and members of the nobility, over precedence and distinctions.

The foreign princes ranked in France above "titular princes" (princes de titre, holders of a legal but foreign title of prince with no association to an hereditary realm), and above most titled nobles, including the highest among these, dukes. They ranked below acknowledged members of the House of Capet, France's ruling dynasty since the tenth century. Included in that royal category (in ascending order) were the so-called princes légitimés (the legitimised natural children, and their male-line descendants, of French kings, e.g. Orleans-Longueville, Bourbon-Vendôme and Bourbon-Penthièvre); the princes du sang (legitimate male-line great-grandchildren, and their male-line descendants, of French kings, e.g. House of Conde, House of Conti, House of Montpensier); and the immediate royal family or famille du roi, consisting of the sovereign, his consort, any queens dowager, and the legitimate children (enfants de France) and male-line grandchildren (petits-enfants de France) of a French king or dauphin). This hierarchy in France evolved slowly at the king's court, barely taking into account any more exalted status a foreign prince might enjoy in his dynasty's realm. It was not clear, outside the halls of the Parlement of Paris, whether foreign princes ranked above, below, or with the holder of a French peerage.

Foreign princes were of three kinds:[2]

- those domiciled in France but recognized by the current king as junior members of dynasties that reigned abroad (e.g., the Guise cadets of the House of Lorraine; the Nevers cadets of Mantua's House of Gonzaga; the Nemours cadets of the Dukes of Savoy). Above them were actual deposed rulers and their consorts (e.g. King James II of England, Queen Christina of Sweden, Duchess Suzanne-Henriette of Mantua, etc.), who were usually accorded full protocolar courtesies at court, for as long as they remained welcome in France.

- rulers of petty principalities who habitually sojourned at the French court (e.g. Princes of Monaco, Dukes of Bouillon).

- French nobles who claimed membership in a formerly sovereign dynasty, either in the male line (e.g. Rohan) or who pretended to a foreign throne as heirs in the female line (e.g. La Trémoïlle).

Status

Like knights-errant of chivalric folklore, whether in exile or in search of royal patronage, to win renown at arms, international influence, or a private fortune, foreign princelings often migrated to the French court, regarded as both the most magnificent and munificent in Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Some ruled small border realms (e.g., the principalities of Dombes, Orange, Neuchâtel, Sedan), while others inherited or were granted large properties in France (e.g., Guise, Rohan, La Tour d'Auvergne). Still others came to France as relatively destitute refugees (e.g. ex-Queen Catherine of England, the Prince Palatine Eduard). Most found that, with assiduity and patience, they were well received by France's kings as living adornments to his majesty and, if they remained in attendance at court, were often gifted with military commands, estates, governorships, embassies, church sinecures, titles and, sometimes, splendid dowries as the consorts of royal princesses (e.g. Louis Joseph de Lorraine, Duke of Guise).

But they were often also disruptive at court and occasionally proved threatening to the king. Their high birth not only attracted the king's attention, but sometimes drew the allegiance of French nobles, frustrated courtiers, soldiers-of-fortune and henchmen, ambitious bourgeoisie, scurrilous malcontents and even provinces in search of a protector (e.g., the Neapolitan Republic)-- often against or in rivalry with the French Crown itself.[2] Deeming themselves to belong to the same class as the king, they tended to be proud, and some schemed for ever-higher rank and power, or challenged the king's or parliament's authority. Sometimes they defied the royal will and barricaded themselves in their provincial castles (e.g., Philippe Emmanuel of Lorraine, duc de Mercœur), occasionally waging open war on the king (e.g., the La Tour d'Auvergne dukes of Bouillon), or intriguing against him with other French princes (e.g., during the Frondes) or with foreign powers (e.g., Marie de Rohan-Montbazon, duchesse de Chevreuse).

Rivalry with peers

Although during formal receptions at court (the so-called Honneurs de la Cour) their sovereign origins were acknowledged in deferential prose, foreign princes were not members by hereditary right of the nation's main judicial and deliberative body, the Parlement of Paris, unless they also held a peerage; in which case, legal precedence derived from its date of registration in that body. Their notorious disputes with ducal peers of the realm, remembered thanks to the memoirs of the duc de Saint-Simon, were due to the princes' lack of rank per se in the Parlement, where peers (the highest tier of French nobility, mostly dukes) held precedence immediately after the princes du sang or, from 4 May 1610, after the legitimised princes.[2] Whereas at the king's table and in society generally, the prestige of the princes étrangers exceeded that of the ordinary peer, the dukes denied this pre-eminence, both in the Montmorency-Luxembourg lawsuit and in the Parlement, regardless of the king's commands.[2]

They also clashed with the upstarts at court favored by Henry III, who raised to peerage, fortune, and singular honor a number of fashionable young men of the minor nobility. These so-called mignons were disdained and resisted by France's princes initially. Later, endowed with hereditary wealth and honors, their families were absorbed into the peerage, and their daughters' dowries were sought by the princely class (e.g., the ducal heiress of Joyeuse married both a duc de Montpensier and a duc de Guise).

More frequently, they vied for place and prestige with each other, with the princes légitimés, and sometimes even with the princes du sang of the House of Bourbon.

Noted Foreign Princes[2]

During the reign of Louis XIV, the families which held the status of prince étranger were:

- Savoy Carignan, cadets of the sovereign Dukes of Savoy

- Guise, cadets of the reigning Dukes of Lorraine

- Rohan, descendants of the extinct Dukes of Brittany

- La Tour d'Auvergne, reigning Dukes of Bouillon

- Grimaldi, ruling Princes of Monaco

- La Trémoïlle, heirs of the body of the deposed Trastámara Kings of Naples (who were also nominal pretenders to the kingdoms of Jerusalem, Cyprus, and Armenia).

Most renowned among the foreign princes was the devoutly Roman Catholic House of Guise which,[2] as the Valois kings approached extinction and the Huguenots aggrandized in defense of Protestantism, cast ambitious eyes upon the throne itself, hoping to occupy it but determined to dominate it. So great was their pride that François, Duke of Guise, although merely a subject, dared to openly court Margaret of Valois, the daughter of Henri II. He was obliged to hastily wed a princesse étrangère (Catherine of Cleves), to avoid bodily harm from Margaret's offended brothers (each of whom eventually succeeded to the crown as, respectively, Francis II, Charles IX and Henry III).[3] After the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre the Guises, triumphant in a kingdom purged of Protestant rivals, proved overbearing toward the king, driving Henry III to have the duke assassinated in his presence.

The status of foreign prince was not automatic: it required the king's acknowledgement and authorization of each of the privileges associated with the status. Some individuals and families claimed entitlement to the rank but never received it. Most infamous among these was Prince Eugene of Savoy, whose cold reception at the court of his mother's family drove him into the arms of the Holy Roman Emperor, where he became the martial scourge of France for a generation.[2][4]

Titles

Most foreign princes did not initially use "prince" as a personal title. Since the families which held that rank were famous and few in the ancien régime, a title carried less distinction than the family surname. Thus noble titles, even chevalier, were commonly and indifferently borne by foreign princes in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries without any implication that their precedence was limited to the rank normally associated with that title. For instance, the title vicomte de Turenne, made famous by the renowned French marshal, merely reflected family tradition. But he ranked as a prince étranger rather than as a viscount, being a cadet of the House of La Tour d'Auvergne, which reigned over the mini-duchy of Bouillon until the French Revolution.

In France, some important seigneuries (lordships) were styled principalities since the late Middle Ages. Their lords had no specific rank, and were always subordinate to dukes and foreign princes. Beginning in the late sixteenth century, some of France's leading families, denied the rank of prince at court, assumed the title of prince (often one held as a subsidiary title, but some did not refrain from inventing titles outright). Often it was claimed on behalf of their eldest sons, subtly reminding the court that the princely title was subordinate — at least in the law — to that of peer, while minimising the risk that the princely style, used as a mere courtesy title, would be challenged or forbidden. Typical were the ducs de La Rochefoucauld: Their claim to descend from the sovereign duke Guillaume IV of Guyenne and their inter-marriages with the sovereign dukes of Mirandola failed to procure for them royal recognition as foreign princes.[5][2] Yet the ducal heir was and is known as the "prince de Marcillac", although no such principality ever existed, within or without France.

In the eighteenth century, as dukes and lesser noblemen arrogated to themselves the title "prince de X", more of the foreign princes began to do likewise. Like the princes du sang (e.g. Condé, La Roche-sur-Yon), it was one of their de facto prerogatives to unilaterally assume a princely titre de courtoisie attached to the name of a seigneurie (e.g., prince d'Harcourt and prince de Lambesc in the House of Lorraine-Guise; prince d'Auvergne and prince de Turenne in the House of La Tour d'Auvergne; prince de Montauban and prince de Rochefort in the House of Rohan; prince de Talmond in the House of La Trémoïlle), even when the eponymous property was no longer held by the family. These titles were then passed down within families as if they were hereditary peerages.[1]

Moreover, some noble titles of prince conferred on Frenchmen by the Holy Roman Empire, the Papacy or Spain were eventually accepted at the French court (e.g., Prince de Broglie, Prince de Beauveau, Prince de Bauffremont) became more common in the eighteenth century. But they carried no official rank, and their social status was not equal to that of either peers or foreign princes.[1]

Unsurprisingly, foreign princes began adopting a custom increasingly common outside of France; prefixing their Christian names with "le prince". The genealogist par excellence of the French nobility, Père Anselme, initially deprecated such neologistic practice with insertion of a "dit" ("styled" or "so-called") in his biographical entries, but after the reign of Louis XIV he records the usage among princes étrangers without qualification.

Privileges

Foreign princes were entitled to the style "haut et puissant prince" ("high and mighty Prince") in French etiquette, were called "cousin" by the king, and claimed the right to be addressed as votre altesse (Your Highness).

Although Saint-Simon and other peers were loath to concede these prerogatives to the princes étrangers, they were even more jealous of two other privileges, the so-called pour ("for") and the tabouret ("stool"). The former referred to the rooms assigned at the palace of Versailles to allow members of the royal dynasty, high-ranking officers of the royal household, senior peers and favored courtiers the honor of living under the same roof as the king. These rooms were neither well-appointed nor well-situated relative to those of the royal family, usually being small and remote. Nonetheless, les pours distinguished the court's inner circle from its hangers-on.

The tabouret was even more highly valued. It consisted of the right to sit on a stool or ployant (folding seat), in the presence of the king or queen. Whereas the queen had her throne, the filles de France and petite-filles their armchairs, and princesses du sang were entitled to cushioned seats with hard backs, duchesses whose husbands were peers sat, gowned and bejewelled, in a semicircle around the queen and lesser royalties, on low, unsteady stools without any back support — and reckoned themselves fortunate among the women of France.

Whereas the wife of a duke-and-peer could use a ployant, other duchesses, domestic or foreign, lacked the prerogative. Not only could the wife of any prince étranger claim a tabouret, but so could his daughters and sisters. This extended privilege was based on the fact that a peer was, legally, an officer of the Parlement of Paris, whereas the rank held by a prince derived from a dignity rooted in his blood line rather than in his function. Thus a duchess-peeress shares in her husband's de jure rank as an official, but that privilege is extended to no other of his family. Yet all daughters and sisters in the legitimate male line of a prince share his blood, and thus his status, as do his wife and the wives of his patrilineage.[2]

List

| Name | Date of recognition | Extinction | Arms | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| House of Lorraine, Dukes of Mercœur | 1569 | 1602 |  |

|

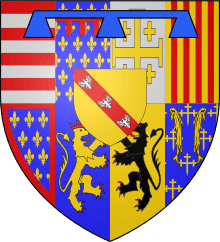

| House of Lorraine, Dukes of Guise | 1528 | 1675 (main line of Guise) 1825 (junior line of Elbeuf) |

|

Cadet branches: Dukes of Mayenne (1544), Dukes of Aumale (1547), Dukes of Elbeuf (1581) |

| House of Savoy, Dukes of Nemours | 1528 | 1659 |  |

|

| House of Savoy, Princes of Carignan | 1642 | extant |  |

|

| House of Cleves, Dukes of Nevers | 1538 | 1565 |  |

|

| House of Gonzaga, Dukes of Nevers | 1566 | 1627 |  |

The Duke of Nevers inherited the Duchy of Mantua and left the French Court in 1627 |

| House of Grimaldi, Princes of Monaco | 1641 | 1731 |  |

The Princes of Monaco were also Dukes of Valentinois in the French Peerage |

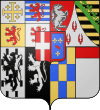

| House of La Tour d'Auvergne, Dukes of Bouillon | 1651 | 1802 |  |

The Dukes of Bouillon were also Dukes of Albret and Château-Thierry in the French Peerage |

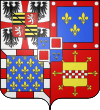

| House of Rohan, Dukes of Montbazon | 1651 | extant |  |

The House of Rohan-Chabot, female-line heirs of the body of the elder branch of the House of Rohan, is extant, bearing the title Duke of Rohan, but was never acknowledged to be of princely rank. |

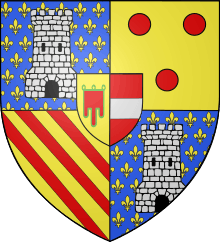

| House of La Trémoille, Dukes of Thouars | 1651 | 1933 |  |

Female-line heirs-in-exile of the Kings of Naples of the House of Trastámara. |

Further reading

- François Velde, a chapter on princes étrangers at Heraldica

- Jean-Pierre Labatut, Les ducs et pairs de France au XVIIe siècle, (Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 1972), pp. 351–71

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Velde, François. "The Rank/Title of Prince in France". Heraldica.org. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 Spanheim, Ézéchiel (1973). ed. Emile Bourgeois, ed. Relation de la Cour de France. le Temps retrouvé (in French). Paris: Mercure de France. p. 104-105, 106-120, 134, 291, 327, 330.

- ↑ "Guise, House of". Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition. Retrieved 2008-05-10.date = 1911|

- ↑ Tourtchine, Jean-Fred. “Le Royaume d’Italie”, Volume II. Cercle d’Etudes des Dynasties Royales Européennes (C.E.D.R.E.), Paris, 1993, p. 64-65. ISSN=0993-3964.

- ↑ University of Chicago, ed. (1990). "La Rochefoucauld Family". New Encyclopædia Britannica - Micropædia. Volume 7 (15th ed.). Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. pp. page 72. ISBN 0-85229-511-1.

The family's claim to princely privileges in France was urged without success in the mid-17th century...