Preventive healthcare

Preventive healthcare (alternately preventive medicine or prophylaxis) consists of measures taken for disease prevention, as opposed to disease treatment.[1][2] Just as health encompasses a variety of physical and mental states, so do disease and disability, which are affected by environmental factors, genetic predisposition, disease agents, and lifestyle choices. Health, disease, and disability are dynamic processes which begin before individuals realize they are affected. Disease prevention relies on anticipatory actions that can be categorized as primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention.[2]

Each year, millions of people die preventable deaths. A 2004 study showed that about half of all deaths in the United States in 2000 were due to preventable behaviors and exposures.[3] Leading causes included cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory disease, unintentional injuries, diabetes, and certain infectious diseases.[3] This same study estimates that 400,000 people die each year in the United States due to poor diet and a sedentary lifestyle.[3] According to estimates made by the World Health Organization (WHO), about 55 million people died worldwide in 2011, two thirds of this group from non-communicable diseases, including cancer, diabetes, and chronic cardiovascular and lung diseases.[4] This is an increase from the year 2000, during which 60% of deaths were attributed to these diseases.[4] Preventive healthcare is especially important given the worldwide rise in prevalence of chronic diseases and deaths from these diseases.

There are many methods for prevention of disease. It is recommended that adults and children aim to visit their doctor for regular check-ups, even if they feel healthy, to perform disease screening, identify risk factors for disease, discuss tips for a healthy and balanced lifestyle, stay up to date with immunizations and boosters, and maintain a good relationship with a healthcare provider.[5] Some common disease screenings include checking for hypertension (high blood pressure), hyperglycemia (high blood sugar, a risk factor for diabetes mellitus), hypercholesterolemia (high blood cholesterol), screening for colon cancer, depression, HIV and other common types of sexually transmitted disease such as chlamydia, syphilis, and gonorrhea, mammography (to screen for breast cancer), colorectal cancer screening, a pap test (to check for cervical cancer), and screening for osteoporosis. Genetic testing can also be performed to screen for mutations that cause genetic disorders or predisposition to certain diseases such as breast or ovarian cancer.[5] However, these measures are not affordable for every individual and the cost effectiveness of preventive healthcare is still a topic of debate.[6][7]

Levels of prevention

Preventive healthcare strategies are typically described as taking place at the primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention levels. In the 1940s, Hugh R. Leavell and E. Gurney Clark coined the term primary prevention. They worked at the Harvard and Columbia University Schools of Public Health, respectively, and later expanded the levels to include secondary and tertiary prevention.[8] Goldston (1987) notes that these levels might be better described as "prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation"[8] though the terms primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention are still commonly in use today.

| Level | Definition |

|---|---|

| Primary prevention | Methods to avoid occurrence of disease either through eliminating disease agents or increasing resistance to disease.[1] Examples include immunization against disease, maintaining a healthy diet and exercise regimen, and avoiding smoking.[9] |

| Secondary prevention | Methods to detect and address an existing disease prior to the appearance of symptoms.[1] Examples include treatment of hypertension (a risk factor for many cardiovascular diseases), cancer screenings [9] |

| Tertiary prevention | Methods to reduce negative impact of symptomatic disease, such as disability or death, through rehabilitation and treatment.[1] Examples include surgical procedures that halt the spread or progression of disease [1] |

Primary prevention

Primary prevention consists of "health promotion" and "specific protection."[1] Health promotion activities are non-clinical life choices, for example, eating nutritious meals and exercising daily, that both prevent disease and create a sense of overall well-being. Preventing disease and creating overall well-being, prolongs our life expectancy.[1][2] Health-promotional activities do not target a specific disease or condition but rather promote health and well-being on a very general level.[2] On the other hand, specific protection targets a type or group of diseases and complements the goals of health promotion.[1] In the case of a sexually transmitted disease such as syphilis health promotion activities would include avoiding microorganisms by maintaining personal hygiene, routine check-up appointments with the doctor, general sex education, etc. whereas specific protective measures would be using prophylactics (such as condoms) during sex and avoiding sexual promiscuity.[2]

Food is very much the most basic tool in preventive health care. The 2011 National Health Interview Survey performed by the Centers for Disease Control was the first national survey to include questions about ability to pay for food. Difficulty with paying for food, medicine, or both is a problem facing 1 out of 3 Americans. If better food options were available through food banks, soup kitchens, and other resources for low-income people, obesity and the chronic conditions that come along with it would be better controlled [10] A “food desert” is an area with restricted access to healthy foods due to a lack of supermarkets within a reasonable distance. These are often low-income neighborhoods with the majority of residents lacking transportation .[11] There have been several grassroots movements in the past 20 years to encourage urban gardening, such as the GreenThumb organization in New York City. Urban gardening uses vacant lots to grow food for a neighborhood and is cultivated by the local residents.[12] Mobile fresh markets are another resource for residents in a “food desert”, which are specially outfitted buses bringing affordable fresh fruits and vegetables to low-income neighborhoods. These programs often hold educational events as well such as cooking and nutrition guidance.[13] Programs such as these are helping to provide healthy, affordable foods to the people who need them the most.

Scientific advancements in genetics have significantly contributed to the knowledge of hereditary diseases and have facilitated great progress in specific protective measures in individuals who are carriers of a disease gene or have an increased predisposition to a specific disease. Genetic testing has allowed physicians to make quicker and more accurate diagnoses and has allowed for tailored treatments or personalized medicine.[2] Similarly, specific protective measures such as water purification, sewage treatment, and the development of personal hygienic routines (such as regular hand-washing) became mainstream upon the discovery of infectious disease agents such as bacteria. These discoveries have been instrumental in decreasing the rates of communicable diseases that are often spread in unsanitary conditions.[2]

Finally, a separate category of health promotion has been propounded, based on the 'new knowledge' in molecular biology - in particular epigenetics - which points to how much physical as well as affective environments during foetal and newborn life may determine adult health.[14] This is commonly called primal prevention. It involves providing future parents with pertinent, unbiased information on primal health and supporting them during their child's primal life (i.e., "from conception to first anniversary" according to definition by the Primal Health Research Centre, London). This includes adequate parental leave - ideally for both parents - with kin caregiving and financial help if needed.

Secondary prevention

Secondary prevention deals with latent diseases and attempts to prevent an asymptomatic disease from progressing to symptomatic disease.[1] Certain diseases can be classified as primary or secondary. This depends on definitions of what constitutes a disease, though, in general, primary prevention addresses the root cause of a disease or injury[1] whereas secondary prevention aims to detect and treat a disease early on.[15] Secondary prevention consists of "early diagnosis and prompt treatment" to contain the disease and prevent its spread to other individuals, and "disability limitation" to prevent potential future complications and disabilities from the disease.[2] For example, early diagnosis and prompt treatment for a syphilis patient would include a course of antibiotics to destroy the pathogen and screening and treatment of any infants born to syphilitic mothers. Disability limitation for syphilitic patients includes continued check-ups on the heart, cerebrospinal fluid, and central nervous system of patients to curb any damaging effects such as blindness or paralysis.[2]

Tertiary prevention

Finally, tertiary prevention attempts to reduce the damage caused by symptomatic disease by focusing on mental, physical, and social rehabilitation. Unlike secondary prevention, which aims to prevent disability, the objective of tertiary prevention is to maximize the remaining capabilities and functions of an already disabled patient.[2] Goals of tertiary prevention include: preventing pain and damage, halting progression and complications from disease, and restoring the health and functions of the individuals affected by disease.[15] For syphilitic patients, rehabilitation includes measures to prevent complete disability from the disease, such as implementing work-place adjustments for the blind and paralyzed or providing counseling to restore normal daily functions to the greatest extent possible.[2]

Leading causes of preventable death

United States

The leading cause of death in the United States was tobacco. However, poor diet and lack of exercise may soon surpass tobacco as a leading cause of death. These behaviors are modifiable and public health and prevention efforts could make a difference to reduce these deaths.[3]

| Cause | Deaths caused | % of all deaths |

|---|---|---|

| Tobacco smoking | 435,000 | 18.1 |

| Poor diet and physical inactivity | 400,000 | 16.6 |

| Alcohol consumption | 85,000 | 3.5 |

| Infectious diseases | 75,000 | 3.1 |

| Toxicants | 55,000 | 2.3 |

| Traffic collisions | 43,000 | 1.8 |

| Firearm incidents | 29,000 | 1.2 |

| Sexually transmitted infections | 20,000 | 0.8 |

| Drug abuse | 17,000 | 0.7 |

Worldwide

The leading causes of preventable death worldwide share similar trends to the United States. There are a few differences between the two, such as malnutrition, pollution, and unsafe sanitation, that reflect health disparities between the developing and developed world.[16]

| Cause | Deaths caused (millions per year) |

|---|---|

| Hypertension | 7.8 |

| Smoking | 5.0 |

| High cholesterol | 3.9 |

| Malnutrition | 3.8 |

| Sexually transmitted infections | 3.0 |

| Poor diet | 2.8 |

| Overweight and obesity | 2.5 |

| Physical inactivity | 2.0 |

| Alcohol | 1.9 |

| Indoor air pollution from solid fuels | 1.8 |

| Unsafe water and poor sanitation | 1.6 |

Infant and child mortality

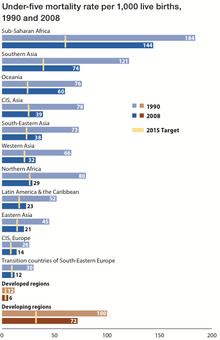

In 2010, 7.6 million children died before reaching the age of 5. While this is a decrease from 9.6 million in the year 2000,[17] it is still far from the fourth Millennium Development Goal to decrease child mortality by two-thirds by the year 2015.[18] Of these deaths, about 64% were due to infection (including diarrhea, pneumonia, and malaria).[17] About 40% of these deaths occurred in neonates (children ages 1–28 days) due to pre-term birth complications.[18] The highest number of child deaths occurred in Africa and Southeast Asia.[17] In Africa, almost no progress has been made in reducing neonatal death since 1990.[18] India, Nigeria, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Pakistan, and China contributed to almost 50% of global child deaths in 2010. Targeting efforts in these countries is essential to reducing the global child death rate.[17]

Child mortality is caused by a variety of factors including poverty, environmental hazards, and lack of maternal education.[19] The World Health Organization created a list of interventions in the following table that were judged economically and operationally "feasible," based on the healthcare resources and infrastructure in 42 nations that contribute to 90% of all infant and child deaths. The table indicates how many infant and child deaths could have been prevented in the year 2000, assuming universal healthcare coverage.[19]

| Intervention | Percent of all child deaths preventable |

|---|---|

| Breastfeeding | 13 |

| Insecticide-treated materials | 7 |

| Complementary feeding | 6 |

| Zinc | 4 |

| Clean delivery | 4 |

| Hib vaccine | 4 |

| Water, sanitation, hygiene | 3 |

| Antenatal steroids | 3 |

| Newborn temperature management | 2 |

| Vitamin A | 2 |

| Tetanus toxoid | 2 |

| Nevirapine and replacement feeding | 2 |

| Antibiotics for premature rupture of membranes | 1 |

| Measles vaccine | 1 |

| Antimalarial intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy | <1% |

Preventive methods for different diseases

Obesity

Obesity is a major risk factor for a wide variety of conditions including cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, certain cancers, and type 2 diabetes. In order to prevent obesity, it is recommended that individuals adhere to a consistent exercise regimen as well as a nutritious and balanced diet. A healthy individual should aim for acquiring 10% of their energy from proteins, 15-20% from fat, and over 50% from complex carbohydrates, while avoiding alcohol as well as foods high in fat, salt, and sugar. Sedentary adults should aim for at least half an hour of moderate-level daily physical activity and eventually increase to include at least 20 minutes of intense exercise, three times a week.[20]

Cancer

In recent years, cancer has become a global problem. Low and middle income countries share a majority of the cancer burden largely due to exposure to carcinogens resulting from industrialization and globalization.[21] However, primary prevention of cancer and knowledge of cancer risk factors can reduce over one third of all cancer cases. Primary prevention of cancer can also prevent other diseases, both communicable and non-communicable, that share common risk factors with cancer.[21]

Lung cancer

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States and Europe and is a major cause of death in other countries.[22] Tobacco is an environmental carcinogen and the major underlying cause of lung cancer.[22] Between 25% and 40% of all cancer deaths and about 90% of lung cancer cases are associated with tobacco use. Other carcinogens include asbestos and radioactive materials.[23] Both smoking and second-hand exposure from other smokers can lead to lung cancer and eventually death.[22] Therefore, prevention of tobacco use is paramount to prevention of lung cancer.

Individual, community, and state-wide interventions can prevent or cease tobacco use. 90% of adults in the US who have ever smoked did so prior to the age of 20. In-school prevention/educational programs, as well as counseling resources, can help prevent and cease adolescent smoking.[23] Other cessation techniques include group support programs, nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), hypnosis, and self-motivated behavioral change. Studies have shown long term success rates (>1 year) of 20% for hypnosis and 10%-20% for group therapy.[23]

Cancer screening programs serve as effective sources of secondary prevention. The Mayo Clinic, Johns Hopkins, and Memorial Sloan-Kettering hospitals conducted annual x-ray screenings and sputum cytology tests and found that lung cancer was detected at higher rates, earlier stages, and had more favorable treatment outcomes, which supports widespread investment in such programs.[23]

Legislation can also have an impact on smoking prevention and cessation. In 1992, Massachusetts (United States) voters passed a bill adding an extra 25 cent tax to each pack of cigarettes, despite intense lobbying and a $7.3 million spent by the tobacco industry to oppose this bill. Tax revenue goes toward tobacco education and control programs and has led to a decline of tobacco use in the state.[24]

Lung cancer and tobacco smoking are making an increasing impact worldwide, especially in China. China is responsible for about one-third of the global consumption and production of tobacco products.[25] Tobacco control policies have been ineffective as China is home to 350 million regular smokers and 750 million passive smokers and the annual death toll is over 1 million.[25] Recommended actions to reduce tobacco use include: decreasing tobacco supply, increasing tobacco taxes, widespread educational campaigns, decreasing advertising from the tobacco industry, and increasing tobacco cessation support resources.[25] In Wuhan, China, a 1998 school-based program, implemented an anti-tobacco curriculum for adolescents and reduced the number of regular smokers, though it did not significantly decrease the number of adolescents who initiated smoking. This program was therefore effective in secondary but not primary prevention and shows that school-based programs have the potential to reduce tobacco use.[26]

Skin cancer

.jpg)

Skin cancer is the most common cancer in the United States.[27] The most lethal form of skin cancer, melanoma, leads to over 50,000 annual deaths in the United States.[27] Childhood prevention is particularly important because a significant portion of ultraviolet radiation exposure from the sun occurs during childhood and adolescence and can subsequently lead to skin cancer in adulthood. Furthermore, childhood prevention can lead to the development of healthy habits that continue to prevent cancer for a lifetime.[27]

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends several primary prevention methods including: limiting sun exposure between 10 AM and 4 PM, when the sun is strongest, wearing tighter-weave natural cotton clothing, wide-brim hats, and sunglasses as protective covers, using sunscreens that protect against both UV-A and UV-B rays, and avoiding tanning salons.[27] Sunscreen should be reapplied after sweating, exposure to water (through swimming for example) or after several hours of sun exposure.[27] Since skin cancer is very preventable, the CDC recommends school-level prevention programs including preventive curricula, family involvement, participation and support from the school's health services, and partnership with community, state, and national agencies and organizations to keep children away from excessive UV radiation exposure.[27]

Most skin cancer and sun protection data comes from Australia and the United States.[28] An international study reported that Australians tended to demonstrate higher knowledge of sun protection and skin cancer knowledge, compared to other countries.[28] Of children, adolescents, and adults, sunscreen was the most commonly used skin protection. However, many adolescents purposely used sunscreen with a low sun protection factor (SPF)in order to get a tan.[28] Various Australian studies have shown that many adults failed to use sunscreen correctly; many applied sunscreen well after their initial sun exposure and/or failed to reapply when necessary.[29][30][31] A 2002 case-control study in Brazil showed that only 3% of case participants and 11% of control participants used sunscreen with SPF >15.[32]

Cervical cancer

Cervical cancer ranks among the top three most common cancers among women in Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, and parts of Asia. Cervical cytology screening aims to detect abnormal lesions in the cervix so that women can undergo treatment prior to the development of cancer. Given that high quality screening and follow-up care has been shown to reduce cervical cancer rates by up to 80%, most developed countries now encourage sexually active women to undergo a pap test every 3–5 years. Finland and Iceland have developed effective organized programs with routine monitoring and have managed to significantly reduce cervical cancer mortality while using fewer resources than unorganized, opportunistic programs such as those in the United States or Canada.[33]

In developing nations in Latin America, such as Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, and Cuba, both public and privately organized programs have offered women routine cytological screening since the 1970s. However, these efforts have not resulted in a significant change in cervical cancer incidence or mortality in these nations. This is likely due to low quality, inefficient testing. However, Puerto Rico, which has offered early screening since the 1960s, has witnessed an almost a 50% decline in cervical cancer incidence and almost a four-fold decrease in mortality between 1950 and 1990. Brazil, Peru, India, and several high-risk nations in sub-Saharan Africa which lack organized screening programs, have a high incidence of cervical cancer.[33]

Colorectal cancer

Colorectal cancer (also called bowel cancer, colon cancer, or rectal cancer) is globally the second most common cancer in women and the third-most common in men,[34] and the fourth most common cause of cancer death after lung, stomach, and liver cancer,[35] having caused 715,000 deaths in 2010.[36]

It is also highly preventable; about 80 percent[37] of colorectal cancers begin as benign growths, commonly called polyps, which can be easily detected and removed during a colonoscopy. Other methods of screening for polyps and cancers include fecal occult blood testing. Lifestyle changes that may reduce the risk of colorectal cancer include increasing consumption of whole grains, fruits and vegetables, and reducing consumption of red meat (see Colorectal cancer).

Health disparities and barriers to accessing care

Access to healthcare and preventive health services is unequal, as is the quality of care received. A study conducted by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)revealed health disparities in the United States. In the United States, elderly adults (>65 years old)received worse care and had less access to care than their younger counterparts. The same trends are seen when comparing all racial minorities (black, Hispanic, Asian) to white patients, and low-income people to high-income people.[38] Common barriers to accessing and utilizing healthcare resources included lack of income and education, language barriers, and lack of health insurance. Minorities were less likely than whites to possess health insurance, as were individuals who completed less education. These disparities made it more difficult for the disadvantaged groups to have regular access to a primary care provider, receive immunizations, or receive other types of medical care.[38] Additionally, uninsured people tend to not seek care until their diseases progress to chronic and serious states and they are also more likely to forgo necessary tests, treatments, and filling prescription medications.[39]

These sorts of disparities and barriers exist worldwide as well. Oftentimes there are decades of gaps in life expectancy between developing and developed countries. For example, Japan has an average life expectancy that is 36 years greater than that in Malawi.[40] Low-income countries also tend to have fewer physicians than high-income countries. In Nigeria and Myanmar, there are fewer than 4 physicians per 100,000 people while Norway and Switzerland have a ratio that is ten-fold higher.[40] Common barriers worldwide include lack of availability of health services and healthcare providers in the region, great physical distance between the home and health service facilities, high transportation costs, high treatment costs, and social norms and stigma toward accessing certain health services.[41]

Effectiveness

There is no general consensus as to whether or not preventive healthcare measures are cost-effective, but they increase the quality of life dramatically. There are varying views on what constitutes a "good investment." Some argue that preventive health measures should save more money than they cost, when factoring in treatment costs in the absence of such measures. Others argue in favor of "good value" or conferring significant health benefits even if the measures do not save money[6][42] Furthermore, preventive health services are often described as one entity though they comprise a myriad of different services, each of which can individually lead to net costs, savings, or neither. Greater differentiation of these services is necessary to fully understand both the financial and health impacts.[6]

A 2010 study reported that in the United States, vaccinating children, cessation of smoking, daily prophylactic use of aspirin, and screening of breast and colorectal cancers had the most potential to prevent premature death.[6] Preventive health measures that resulted in savings included vaccinating children and adults, smoking cessation, daily use of aspirin, and screening for issues with alcoholism, obesity, and vision failure.[6] These authors estimated that if usage of these services in the United States increased to 90% of the population, there would be net savings of $3.7 billion, which comprised only about -0.2% of the total 2006 United States healthcare expenditure.[6] Despite the potential for decreasing healthcare spending, utilization of healthcare resources in the United States still remains low, especially among Latinos and African-Americans.[43] Overall, preventive services are difficult to implement because healthcare providers have limited time with patients and must integrate a variety of preventive health measures from different sources.[43]

While these specific services bring about small net savings not every preventive health measure saves more than it costs. A 1970's study showed that preventing heart attacks by treating hypertension early on with drugs actually did not save money in the long run. The money saved by evading treatment from heart attack and stroke only amounted to about a quarter of the cost of the drugs.[44][45] Similarly, it was found that the cost of drugs or dietary changes to decrease high blood cholesterol exceeded the cost of subsequent heart disease treatment.[46][47] Due to these findings, some argue that rather than focusing healthcare reform efforts exclusively on preventive care, the interventions that bring about the highest level of health should be prioritized.[42]

Cohen et al. (2008) outline a few arguments made by skeptics of preventive healthcare. Many argue that preventive measures only cost less than future treatment when the proportion of the population that would become ill in the absence of prevention is fairly large.[7] The Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group conducted a 2012 study evaluating the costs and benefits (in quality-adjusted life-years or QALY's) of lifestyle changes versus taking the drug metformin. They found that neither method brought about financial savings, but were cost-effective nonetheless because they brought about an increase in QALY's.[48] In addition to scrutinizing costs, preventive healthcare skeptics also examine efficiency of interventions. They argue that while many treatments of existing diseases involve use of advanced equipment and technology, in some cases, this is a more efficient use of resources than attempts to prevent the disease.[7] Cohen et al. (2008) suggest that the preventive measures most worth exploring and investing in are those that could benefit a large portion of the population to bring about cumulative and widespread health benefits at a reasonable cost.[7]

See also

- American Board of Preventive Medicine

- American Osteopathic Board of Preventive Medicine

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- Chronic (medicine)

- Epidemiology

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC)

- Mental illness prevention

- Monitoring (medicine)

- Pre-exposure prophylaxis

- Preventive Medicine (journal)

- Primary Care

- Primary Health Care

- Screening (medicine)

- United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)

- Vaccination

- World Health Organization (WHO)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 Katz, D., & Ather, A. (2009). Preventive Medicine, Integrative Medicine & The Health of The Public. Commissioned for the IOM Summit on Integrative Medicine and the Health of the Public. Retrieved from http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Activity%20Files/Quality/IntegrativeMed/Preventive%20Medicine%20Integrative%20Medicine%20and%20the%20Health%20of%20the%20Public.pdf

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 2.10 Hugh R. Leavell and E. Gurney Clark as "the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life, and promoting physical and mental health and efficiency. Leavell, H. R., & Clark, E. G. (1979). Preventive Medicine for the Doctor in his Community (3rd ed.). Huntington, NY: Robert E. Krieger Publishing Company.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Mokdad, A. H., Marks, J. S., Stroup, D. F., & Gerberding, J. L. (2004). Actual Causes of Death in the United States, 2000. Journal of the American Medical Association,291(10), 1238-1245.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 The Top 10 Causes of Death. (n.d.). Retrieved March 16, 2014, from World Health Organization website: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs310/en/index2.html

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Vorvick, L. (2013). Preventive health care. In D. Zieve, D. R. Eltz, S. Slon, & N. Wang (Eds.), The A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/encyclopedia.html

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Michael V. Maciosek, Ashley B. Coffield, Thomas J. Flottemesch, Nichol M. Edwards and Leif I. Solberg. Greater Use Of Preventive Services In U.S. Health Care Could Save Lives At Little Or No Cost. Health Affairs, 29, no.9 (2010):1656-1660. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2008.0701.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Cohen, J. T., Neumann, P. J., & Weinstein, M. C. (2008, February 14). Does Preventive Care Save Money? Health Economics and the Presidential Candidates. The New England Journal of Medicine, 358(7), 661-663.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Goldston, S. E. (Ed.). (1987). Concepts of primary prevention: A framework for program development. Sacramento: California Department of Mental Health

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Patterson, C., & Chambers, L. W. (1995). Preventive health care. The Lancet, 345, 1611-1615.

- ↑ Marucs, Erin. "Access to Good Food as Preventive Medicine". The Atlantic. Atlantic Media Company. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- ↑ "Food Deserts". Food is Power.org. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- ↑ [. http://www.greenthumbnyc.org "GreenThumb"]. NYC Parks. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- ↑ "It's a Market on a Bus". Twin Cities Mobile Market. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- ↑ Effect of In Utero and Early-Life Conditions on Adult Health and Disease, Peter D. Gluckman et al., The New England Journal of Medicine, 359;1, 2008

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Module 13: Levels of Disease Prevention. (2007, April 24). Retrieved March 16, 2014, from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website: http://www.cdc.gov/excite/skincancer/mod13.htm

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ (May 2006). "Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data". Lancet 367 (9524): 1747–57.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Liu, L., Johnson, H. L., Cousens, S., Perin, J., Scott, S., Lawn, J. E., ... Black, R. E. (2012). Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: an updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. The Lancet, 379(9832), 2151–2161.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Countdown to 2015, decade report (2000–10)—taking stock of maternal, newborn and child survival WHO, Geneva (2010)

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Jones G, Steketee R, Black R, Bhutta Z, Morris S, and the Bellagio Child Survival Study Group* (5 July 2003). "How many child deaths can we prevent this year?". Lancet 362 (9524): 1747–57.

- ↑ Kumanyika, S., Jeffery, R. W., Morabia, A., Ritenbaugh, C., & Antipatis, V. J. (2002). Obesity prevention: the case for action. International Journal of Obesity, 26, 425-436.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Vineis, P., & Wild, C. P. (2014). Global cancer patterns: causes and prevention. The Lancet, 383(9916), 487.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Goodman, G. E. (2000). Prevention of lung cancer. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology, 33(3), 187-197.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Risser, N. L. (1996). Prevention of Lung Cancer: The Key Is to Stop Smoking . Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 12, 260-269.

- ↑ Koh, H. K. (1996). An analysis of the successful 1992 Massachusetts tobacco tax initiative. Tobacco Control, 5, 220-225.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Zhang, J., Ou, J., & Bai, C. (2011). Tobacco smoking in China: Prevalence, disease burden, challenges and future strategies. Respirology, 16(8), 1165-1172.

- ↑ Chou, C. P., Li, Y., Unger, J. B., Xia, J., Sun, P., Guo, Q., ... Johnson, C. A. (2006). A randomized intervention of smoking for adolescents in urban Wuhan, China. Preventive Medicine, 42(4), 280-285.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 27.5 MMWR. Recommendations and Reports : Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Recommendations and Reports / Centers for Disease Control [2002, 51(RR-4):1-18]

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Stanton, W. R., Janda, M., Baade, P. D., & Anderson, P. (2004). Primary prevention of skin cancer: a review of sun protection in Australia and internationally. Health Promotion International, 19(3), 369-378

- ↑ Broadstock, M. (1991) Sun protection at cricket. Medical Journal of Australia, 154, 430.

- ↑ Pincus, M. W., Rollings, P. K., Craft, A. B. and Green, B. (1991) Sunscreen use on Queenslands beaches. Australasian Journal of Dermatology, 32, 21–25.

- ↑ Hill, D., White, V., Marks, R., Theobald, T., Borland, R. and Roy, C. (1992) Melanoma prevention: behavioural and non-behavioural factors in sunburn among and Australian urban population. Preventive Medicine, 21, 654–669.

- ↑ Bakos, L., Wagner, M., Bakos, R. M., Leite, C. S. M., Sperhacke, C. L., Dzekaniak, K. S. et al. (2002) Sunburn, sunscreens, and phenotypes: some risk factors for cutaneous melanoma in southern Brazil. International Journal of Dermatology, 41, 557–562.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Sankaranarayanan, R., Budukh, A. M., & Rajkumar, R. (2001). Effective screening programmes for cervical cancer in low- and middle-income developing countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 79(10), 954-962.

- ↑ World Cancer Report 2014. International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization. 2014. ISBN 978-92-832-0432-9.

- ↑ "Cancer". World Health Organization. February 2010. Retrieved January 5, 2011.

- ↑ Lozano R; Naghavi M; Foreman K et al. (December 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. PMID 23245604.

- ↑ Carol A. Burke & Laura K. Bianchi. "Colorectal Neoplasia". Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Disparities in Healthcare Quality Among Racial and Ethnic Groups: Selected Findings from the 2011 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Reports. Fact Sheet. AHRQ Publication No. 12-0006-1-EF, September 2012. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/nhqrdr11/nhqrdrminority11.htm

- ↑ J. Emilio Carrillo. and Victor A. Carrillo. and Hector R. Perez. and Debbie Salas-Lopez. and Ana Natale-Pereira. and Alex T. Byron. "Defining and Targeting Health Care Access Barriers." Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 22.2 (2011): 562-575. Project MUSE. Web. 25 Apr. 2014. <http://muse.jhu.edu/>.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Fact file on health inequities. (n.d.). Retrieved April 25, 2014, from World Health Organization website: http://www.who.int/sdhconference/background/news/facts/en/

- ↑ Jacobs, B., Ir, P., Bigdeli, M., Annear, P. L., & Damme, W. V. (2011). Addressing access barriers to health services: an analytical framework for selecting appropriate interventions in low-income Asian countries. Health Policy and Planning, 1-13.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 The role of prevention in health reform. N Engl J Med 1993;329:352-354

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Maciosek MV, Coffield AB, Edwards NM, Flottemesch TJ, Goodman MJ, Solberg LI. Priorities among effective clinical preventive services: results of a systematic review and analysis. Am J Prev Med 2006;31:52-61

- ↑ Weinstein MC, Stason WB. Hypertension: a policy perspective. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1976.

- ↑ Weinstein MC, Stason WB. Economic considerations in the management of mild hypertension. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1978;304:424-440

- ↑ Taylor WC, Pass TM, Shepard DS, Komaroff AL. Cost effectiveness of cholesterol reduction for the primary prevention of coronary heart disease in men. In: Goldbloom RB, Lawrence RS, eds. Preventing disease: beyond the rhetoric. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1990:437-41.

- ↑ Goldman L, Weinstein MC, Goldman PA, Williams LW. Cost-effectiveness of HMG-CoA reductase inhibition for primary and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. JAMA 1991;265:1145-1151

- ↑ The Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group (2012). The 10-Year Cost-Effectiveness of Lifestyle Intervention or Metformin for Diabetes Prevention. Diabetes Care, 35, 723-730.

External links

- United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||