Pre-Roman Iron Age

The Pre-Roman Iron Age of Northern Europe (5th/4th - 1st century BC) was the earliest part of the Iron Age in Scandinavia, northern Germany, and the Netherlands north of the Rhine River.[1] These regions feature many extensive archaeological excavation sites, which have yielded a wealth of artifacts. Objects discovered at the sites suggest that the Pre-Roman Iron Age cultures evolved without a major break out of the Nordic Bronze Age, but that there were strong influences from the Celtic Iron-Age Hallstatt culture in Central Europe. During the 1st century BC, Roman influence began to be felt even in Denmark.[2]

Overview

Archaeologists first made the decision to divide the Iron Age of Northern Europe into distinct pre-Roman and Roman Iron Ages after Emil Vedel unearthed a number of Iron Age artifacts in 1866 on the island of Bornholm.[3] They did not exhibit the same permeating Roman influence seen in most other artifacts from the early centuries AD, indicating that parts of northern Europe had not yet come into contact with the Romans at the beginning of the Iron Age.

Out of the Late Bronze Age Urnfield culture of the 12th century BCE developed the Early Iron Age Hallstatt culture of Central Europe from the 8th to 6th centuries BCE, which was followed by the La Tène culture of Central Europe (450 BCE to 1st century BCE). Albeit the metal iron came into wider use by metalworkers in the Mediterranean as far back as c. 1300 BCE due to the Bronze Age Collapse, the Pre-Roman Iron Age of Northern Europe started only as early as the 5th/4th to the 1st century BCE. The Iron Age in northern Europe is markedly distinct from the Celtic La Tène culture south of it, whose advanced iron-working technology exerted a considerable influence in the north, when, around 600 BC northern people began to extract bog iron from the ore in peat bogs, a technology acquired from their Central European neighbours. The oldest iron objects found have been needles, but edged tools, swords and sickles, are found as well. Bronze continued to be used during the whole period, but was mostly used for decoration.

Funerary practices continued the Bronze Age tradition of burning the corpses and placing the remains in urns, a characteristic of the Urnfield culture. During the previous centuries, influences from the Central European La Tène culture spread to Scandinavia from north-western Germany, and there are finds from this period from all the provinces of southern Scandinavia. Archaeologists have found swords, shield bosses, spearheads, scissors, sickles, pincers, knives, needles, buckles, kettles, etc. from this time. Bronze continued to be used for torcs and kettles, the style of which were continuous from the Bronze Age. Some of the most prominent finds are the Gundestrup silver cauldron and the Dejbjerg wagons from Jutland, two four-wheeled wagons of wood with bronze parts.

Historic references

In Southern Europe Mediterranean climates, the forest at that time, immemorial for the most part, was open evergreen leaves and pine forests. After slash and burn, this forest had less capacity for regeneration than the forest north of the Alps.

In Northern Europe, there was usually only one crop harvested before grass growth took over, while in the south, suitable fall was used for several years and the soil was quickly exhausted. Slash and burn shifting cultivation therefore ceased much earlier in the south than the north. Most of the forests in the Mediterranean had disappeared by classical times. The classical authors wrote about the great forests (Semple 1931 261-296).[4]

Homer writes of wooded Samothrace, Zacynthos, Sicily and other wooded land.[5] The authors give us the general impression that the Mediterranean countries had more forest than now, but that it had already lost much forest, and that it was left there in the mountains (Darby 1956 186).[6]

It is clear that Europe remained wooded, and not only in the north. However, during the Roman Iron Age and early Viking Age, forest areas drastically reduced in Northern Europe, and settlements were regularly moved. There is no good explanation for this mobility, and the transition to stable settlements from the late Viking period, as well as the transition from shifting cultivation to stationary use of arable land. At the same time plows appears as a new group of implements were found both in graves and in depots. It can be confirmed that early agricultural people preferred forest of good quality in the hillside with good drainage, and traces of cattle quarters are evident here.

The Greek explorer and merchant Pytheas of Marseilles made a voyage to Northern Europe ca. 330 BC. Part of his itinerary is kept at Polybios, Pliny and Strabo. Pytheas had visited Thule, which lay a six-day voyage north of Britain. There "the barbarians showed us the place where the sun does not go to sleep. It happened because there the night was very short -- in some places two, in others three hours -- so that the sun shortly after its fall soon went up again." He says that Thule was a fertile land, "rich in fruits that were ripe only until late in the year, and the people there used to prepare a drink of honey. And they threshed the grain in large houses, because of the cloudy weather and frequent rain. In the spring they drove the cattle up into the mountain pastures and stayed there all summer. " This description may fit well on the West-Norwegian conditions. Here is an instance of both dairy farming and drying/threshing in a building.

In Italy, shifting cultivation was a thing of the past at the birth of Christ. Tacitus describes it as the strange cultivation methods he had experienced among the Germans, whom he knew well from his stay with them. Rome was entirely dependent on shifting cultivation by the barbarians to survive and maintain "Pax Romana", but when the supply from the colonies "trans alpina" failed, the Roman Empire collapsed.

Tacitus writes in 98 AD about the Germans: fields are proportionate to the participating growers, but they share their crops with each other by reputation. Distribution is easy because there is great access to land. They change soil every year, and mark some off to spare, for they seek not a strenuous job in cramming this fertile and vast land even greater ydelser, by planting apple orchards, cultivated spesial beds or watering gardens; grain is the only thing they insist that the ground will provide. The original text reads,[7] "agri pro numero cultorum ad universis vicinis occupantur, quos mox inter se secundum dignationem partientur, facilitate partiendi camporum spatial praestant, arva per annos mutant, et superest ager, nec enim cum ubertate et amplitudine soli labore contendunt, ut pomaria conserant et prata separent et hortos rigent, sola terrae seges imperatur." Tacitus discusses the shifting cultivation [8]

The Migration Period in Europe after the Roman Empire and immediately before the Viking Age suggests that it was still more profitable for the peoples of Central Europe to move on to new forests after the best parcels were exhausted than to wait for the new forest to grow up. Therefore, the peoples of the temperate zone in Europe slash and burners, remained for as long as the forests permitted. This exploitation of forests explains this rapid and elaborate move. But the forest could not tolerate this in the long run; it first ended in the Mediterranean. The forest here did not have the same vitality as the powerful coniferous forest in Central Europe. Deforestation was partly caused by burning for pasture fields. Missing timber delivery led to higher prices and more stone constructions in the Roman Empire (Stewart 1956 123).[9]

The forest also decreased gradually northwards in Europe, but in the Nordic countries it has survived. The clans in pre-Roman Italy seemed to be living in temporary locations rather than established cities. They cultivated small patches of land, guarded their sheep and their cattle, traded with foreign merchants, and at times fought with one another: etruscans, umbriere, ligurianere, sabinere, Latinos, campaniere, apulianere, faliscanere, and samniter, just to mention a few. These Italic ethnic groups developed identities as settlers and warriors ca. 900 BC. They built forts in the mountains, today a subject of much investigation. The forest has hidden them for a long time, but eventually they will provide information about the people who built and used these buildings. The ruin of a large samnittisk temple and theater at Pietrabbondante is under investigation. These cultural relics have slumbered in the shadow of the glorious history of the Roman Empire.

Many of the Italic tribes realized the benefits of allying with the powerful Romans. When Rome built the Via Amerina 241 BC, the Faliscan people established themselves in cities on the plains, and they collaborated with the Romans on road construction. The Roman Senate gradually gained representatives from many Faliscan and Etruscan families. The Italic tribes are now settled farmers. (Zwingle, National Geographic, January 2005).[10]

An edition of Commentarii de Bello Gallico from the 800AD. Julius Caesar wrote about Svebians, "Commentarii de Bello Gallico, "book 4.1; they are not by private and secluded fields, "privati ac separati agri apud eos nihil est", they cannot stay more than one year in a place for cultivation’s sake, "Neque longius anno remanere uno in loco colendi causa licet ". The Svebes lived between the Rhine and the Elbe. About the Germans, he wrote: No one has a particular field or area for themselves, for the magistrates and chiefs give fields every year to the people and the clans, which have gathered so much ground in such places that it seems good for them to continue on to somewhere else after a year. "Neque quisquam agri modum certum aut fines habet proprios, sed magistratus ac principes in annos singulos gentibus cognationibusque hominum, qui tum una coierunt, a quantum et quo loco visum est agri attribuunt atque anno post alio transire cogunt" book 6, 22.

Strabo (63 BC - about 20 AD) also writes about sveberne in Geographicon VII, 1, 3. Common to all the people in this area is that they can easily change residence because of their sordid way of life; that they do not grow any fields and do not collect property, but live in temporary huts. They get their nourishment from their livestock for the most part, and like nomads, they pack all their goods in wagons and go on to wherever they want. Horazius writes in 17 BC (Carmen säculare, 3, 24, 9 ff .) about the people of Macedonia. The proud Getae also live happily, growing free food and cereal for themselves on land that they do not want to cultivate for more than a year, "vivunt et rigidi Getae, immetata quibus iugera liberal fruges et Cererem freunt, nec cultura placet longior annua." Several classical writers have descriptions of shifting cultivation people. Many peoples’ various shifting cultivations characterized the migration Period in Europe. The exploitation of forests demanded constant displacement, and large areas were deforested.

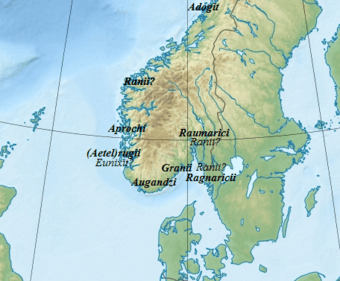

Locations of the tribes described by Jordanes in Norway, contemporary with, and some possibly ruled by Rodulf. Jordanes was of Gothic descent and ended up as a monk in Italy. In his work De origine actibusque Getarum (The Origin and Deeds of the Getae/Goths[11]),[12] the Gothic origins and achievements, the author of 550 AD provides information on the big island Scandza, which the Goths come from. He expects that of the tribes who live here, some are adogit living far north with 40 days of the midnight sun. After adogit come screrefennae and suehans who also live in the north. Screrefennae moved a lot and did not bring to the field crops, but made their living by hunting and collecting bird eggs. Suehans was a seminomadic tribe that had good horses like Thüringians and ran fur hunting to sell the skins. It was too far north to grow grain. Prokopios, ca. 550 AD, also describes a primitive hunter people he calls skrithifinoi. These pitiful creatures had neither wine nor corn, for they did not grow any crops. "Both men and women engaged incessantly just in hunting the rich forests and mountains, which gave them an endless supply of game and wild animals." Screrefennae and skrithifinoi is well Sami who often have names such as; skridfinner, which is probably a later form, derived from skrithibinoi or some similar spelling. The two old terms, screrefennae and skrithifinoi, are probably origins in the sense of neither ski nor finn. Furthermore, in Jordanes' ethnographic description of Scandza are several tribes, and among these are finnaithae "who was always ready for battle" Mixi evagre and otingis that should have lived like wild beasts in mountain caves, "further from them" lived osthrogoth, raumariciae, ragnaricii, finnie, vinoviloth and suetidi that would last prouder than other people.

Adam of Bremen describes Sweden, according to information he received from the Danish king Sven Estridson or also called Sweyn II of Denmark in 1068: "It is very fruitful, the earth holds many crops and honey, it has a greater livestock than all other countries, there are a lot of useful rivers and forests, with regard to women they do not know moderation, they have for their economic position two, three, or more wives simultaneously, the rich and the rulers are innumerable." The latter indicates a kind of extended family structure, and that forests are specifically mentioned as useful may be associated with shifting cultivation and livestock. The "livestock grazing, as with the Arabs, far out in the wilderness" can be interpreted in the same direction.

Expansion

The cultural change that ended the Bronze Age was affected by the expansion of Hallstatt culture from the south and accompanied by a deteriorating climate, which caused a dramatic change in the flora and fauna. In Scandinavia, this period is often called the Findless Age due to the lack of finds. While the finds from Scandinavia are consistent with a loss of population, the southern part of the culture, the Jastorf culture, was in expansion southwards. It consequently appears that the climate change played an important role in the southward expansion of the tribes, considered Germanic, into continental Europe . There are differing schools of thought on the interpretation of geographic spread of cultural innovation, whether new material culture reflects a possibly warlike movement of peoples ("demic diffusion") southwards or whether innovations found at Pre-Roman Iron Age sites represents a more peaceful cultural diffusion. The current view in the Netherlands hold that Iron Age innovations, starting with Hallstatt (800 BC), did not involve intrusions and featured a local development from Bronze Age culture.[13] Another Iron Age nucleus considered to represent a local development is the Wessenstedt culture (800 - 600 BC).

The bearers of this northern Iron Age culture were likely speakers of Germanic languages. The stage of development of this Germanic is not known, although Proto-Germanic has been proposed. The late phase of this period sees the beginnings of the Germanic migrations, starting with the invasions of the Teutons and the Cimbri until their defeat at the Battle of Aquae Sextiae in 102 BC, presaging the more turbulent Roman Iron Age and Age of Migrations.

See also

- Iron Age stone circles

- Germanic tribes

- Urnfield culture

- Jastorf culture

- Hjortspring boat

- Bog bodies

Notes

- ↑ The British Iron Age is treated separately.

- ↑ Dina P. Dobson, "Roman Influence in the North" Greece & Rome 5.14 (February 1936:73-89).

- ↑ Vedel, Bornholms Oldtidsminder og Oldsager, (Copenhagen 1886).

- ↑ Semple E.C.1931, Ancient Mediterranean Forests and the Lumber Trade II Henry Holt et al., The Geography of the Mediterranean region, New York.

- ↑ Homer Iliad, XIII, XIV ---- 0.1 to 2.

- ↑ Darby H.C. 1950, Domesday Woodland II Economic History Review, 2d ser.,III, London. 1956, The clearing of the Woodland in Europe II

- ↑ Perkins and Marvin, Ex Editione Oberliniana, Harvard College Library, 1840 (Xxvi, 15-23).

- ↑ A W Liljenstrand wrote 1857 in his doctoral dissertation, "About changing of soil" (p. 5 ff.), That Tacitus discusses the shifting cultivation: "arva per annos mutant".

- ↑ Stewart O.C. 1956, Fire as the First Great Force Employde by Man II Thomas W.L. Man's role in changing the face of the earth, Chicago.

- ↑ Zwingle E. 2005, Italy before the Romans/!National Geographic, jan.Washington.

- ↑ Late antique writers commonly used Getae for Goths mixing the peoples in the process.

- ↑ G. Costa, 32. Also: De Rebus Geticis: O. Seyffert, 329; De Getarum (Gothorum) Origine et Rebus Gestis: W. Smith, vol 2 page 607

- ↑ Leo Verhart Op Zoek naar de Kelten, Nieuwe archeologische ontdekkingen tussen Noordzee en Rijn, 2006, p67 ISBN 90-5345-303-2.

References

![]() This article contains content from the Owl Edition of Nordisk familjebok, a Swedish encyclopedia published between 1904 and 1926, now in the public domain.

This article contains content from the Owl Edition of Nordisk familjebok, a Swedish encyclopedia published between 1904 and 1926, now in the public domain.

- J. Brandt, Jastorf und Latène. Internat. Arch. 66 (2001)

- John Collis, The European Iron Age (London and New York: Routledge) 1997. The European Iron Age set in a broader context that includes the Mediterranean and Anatolia.

- W. Künnemann, Jastorf - Geschichte und Inhalt eines archäologischen Kulturbegriffs, Die Kunde N. F. 46 (1995), 61-122.

- Herwig Wolfram, Die Germanen, Beck (1999).

- Ove Eriksson, B, Sara, O. Cousins, and Hans Henrik Bruun, "Land-use history and fragmentation of traditionally managed grasslands in Scandinavia" Journal of Vegetation Science pp. 743–748 (On-line abstract)

External links

| ||||||