Pound–Rebka experiment

The Pound–Rebka experiment is a well known experiment to test Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity. It was proposed by Robert Pound and his graduate student Glen A. Rebka Jr. in 1959,[1] and was the last of the classical tests of general relativity to be verified (in the same year). It is a gravitational redshift experiment, which measures the redshift of light moving in a gravitational field, or, equivalently, a test of the general relativity prediction that clocks should run at different rates at different places in a gravitational field. It is considered to be the experiment that ushered in an era of precision tests of general relativity.

Overview

The experiment is based on the principle that when an atom transitions from an excited state to a ground state, it emits a photon with a characteristic frequency and energy. Conversely, when an atom of the same species, in its ground state, encounters a photon with the same characteristic frequency and energy, it will absorb the photon and transition to the excited state. If the photon's frequency and energy is different by even a small amount, the atom cannot absorb it (this is the basis of Quantum Mechanics). When the photon travels through a gravitational field, its frequency, as well as its energy, will change due to the Gravitational Redshift. As a result, the receiving atom cannot absorb it. But if the emitting atom moves with just the right speed relative to the receiving atom the resulting doppler shift cancels out the gravitational shift and the receiving atom can now absorb the photon. The "right" relative speed of the atoms is therefore a measure of the gravitational shift. The frequency of a photon "falling" towards the earth is blueshifted.

The gravitational force was produced by the Earth's field, and because of this, is considered a verification of general relativity in the "weak-field" limit, i.e. where we have Linearized Gravity, as opposed to the "strong-field" regime, i.e. near a Neutron Star, or Black Hole. For clarity, the experiment was made with one atom emitting a photon up, toward the top of the tower, while the receiving atom moved down, in order to correct for the redshift. Pound and Rebka countered the gravitational blueshift by moving the emitter away from the receiver, thus generating a relativistic Doppler redshift:

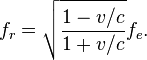

Special Relativity predicts a Doppler redshift of :

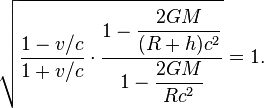

On the other hand, General Relativity predicts a gravitational blueshift of:

The detector at the bottom sees a superposition of the two effects. The emitter was moved vertically and the speed was varied until the two effects cancelled each other, a phenomenon detected by reaching resonance. Mathematically:

In the case of the Pound–Rebka experiment  . Therefore:

. Therefore:

= 7.5×10−7 m/s

= 7.5×10−7 m/s

In the more general case when h ≈ R the above is no longer true. The energy associated with gravitational redshift over a distance of 22.5 meters is very small. The fractional change in energy is given by δE/E, is equal to gh/c2 = 2.5×10−15. Therefore short wavelength high energy photons are required to detect such minute differences. The 14 keV gamma rays emitted by iron-57 when it transitions to its base state proved to be sufficient for this experiment.

Normally, when an atom emits or absorbs a photon, it also moves (recoils) a little, which takes away some energy from the photon due to the principle of conservation of momentum.

The Doppler shift required to compensate for this recoil effect would be much larger (about 5 orders of magnitude) than the Doppler shift required to offset the gravitational redshift. But in 1958 Mössbauer reported that all atoms in a solid lattice absorb the recoil energy when a single atom in the lattice emits a gamma ray. Therefore the emitting atom will move very little (just as a cannon will not produce a large recoil when it is braced, e.g. with sandbags).

This allowed Pound and Rebka to set up their experiment as a variation of Mössbauer spectroscopy.

The test was carried out at Harvard University's Jefferson laboratory. A solid sample containing iron (57Fe) emitting gamma rays was placed in the center of a loudspeaker cone which was placed near the roof of the building. Another sample containing 57Fe was placed in the basement. The distance between this source and absorber was 22.5 meters (73.8 ft). The gamma rays traveled through a Mylar bag filled with helium to minimize scattering of the gamma rays. A scintillation counter was placed below the receiving 57Fe sample to detect the gamma rays that were not absorbed by the receiving sample. By vibrating the speaker cone the gamma ray source moved with varying speed, thus creating varying Doppler shifts. When the Doppler shift canceled out the gravitational blueshift, the receiving sample absorbed gamma rays and the number of gamma rays detected by the scintillation counter dropped accordingly. The variation in absorption could be correlated with the phase of the speaker vibration, hence with the speed of the emitting sample and therefore the doppler shift. To compensate for possible systematic errors, Pound and Rebka varied the speaker frequency between 10 Hz and 50 Hz, interchanged the source and absorber-detector, and used different speakers (ferroelectric and moving coil magnetic transducer).[2] The reason for exchanging the positions of the absorber and the detector is doubling the effect. Pound subtracted two experimental results:

(1) the frequency shift with the source at the top of the tower

(2) the frequency shift with the source at the bottom of the tower

The frequency shift for the two cases has the same magnitude but opposing signs. When subtracting the results, Pound and Rebka obtained a result twice as big as for the one-way experiment.

The result confirmed that the predictions of general relativity were borne out at the 10% level.[3] This was later improved to better than the 1% level by Pound and Snider.[4]

Another test involving a space-borne hydrogen maser increased the accuracy of the measurement to about 10−4 (0.01%).[5]

References

- ↑ Pound, R. V.; Rebka Jr. G. A. (November 1, 1959). "Gravitational Red-Shift in Nuclear Resonance". Physical Review Letters 3 (9): 439–441. Bibcode:1959PhRvL...3..439P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.3.439.

- ↑ Mester, John (2006). "Experimental Tests of General Relativity" (PDF). pp. 9–11. Retrieved 2007-04-13.

- ↑ Pound, R. V.; Rebka Jr. G. A. (April 1, 1960). "Apparent weight of photons". Physical Review Letters 4 (7): 337–341. Bibcode:1960PhRvL...4..337P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.4.337.

- ↑ Pound, R. V.; Snider J. L. (November 2, 1964). "Effect of Gravity on Nuclear Resonance". Physical Review Letters 13 (18): 539–540. Bibcode:1964PhRvL..13..539P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.13.539.

- ↑ Vessot, R. F. C.; M. W. Levine, E. M. Mattison, E. L. Blomberg, T. E. Hoffman, G. U. Nystrom, B. F. Farrel, R. Decher, P. B. Eby, C. R. Baugher, J. W. Watts, D. L. Teuber and F. D. Wills (December 29, 1980). "Test of Relativistic Gravitation with a Space-Borne Hydrogen Maser". Physical Review Letters 45 (26): 2081–2084. Bibcode:1980PhRvL..45.2081V. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.45.2081.