Potential game

In game theory, a game is said to be a potential game if the incentive of all players to change their strategy can be expressed using a single global function called the potential function. Robert W. Rosenthal created the concept of a congestion game in 1973. Monderer and Shapley (1996) created the concept of a potential game and proved that every congestion game is a potential game.

The properties of several types of potential games have since been studied. Games can be either ordinal or cardinal potential games. In cardinal games, the difference in individual payoffs for each player from individually changing one's strategy ceteris paribus has to have the same value as the difference in values for the potential function. In ordinal games, only the signs of the differences have to be the same.

The potential function is a useful tool to analyze equilibrium properties of games, since the incentives of all players are mapped into one function, and the set of pure Nash equilibria can be found by locating the local optima of the potential function. Convergence and finite-time convergence of an iterated game towards a Nash equilibrium can also be understood by studying the potential function.

Definition

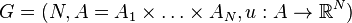

We will define some notation required for the definition. Let  be the number of players,

be the number of players,  the set of action profiles over the action sets

the set of action profiles over the action sets  of each player and

of each player and  be the payoff function.

be the payoff function.

A game  is:

is:

- an exact potential game if there is a function

such that

such that  ,

,

- That is: when player

switches from action

switches from action  to action

to action  , the change in the potential equals the change in the utility of that player.

, the change in the potential equals the change in the utility of that player.

- That is: when player

- a weighted potential game if there is a function

and a vector

and a vector  such that

such that  ,

,

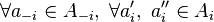

- an ordinal potential game if there is a function

such that

such that  ,

,

- a generalized ordinal potential game if there is a function

such that

such that  ,

,

- a best-response potential game if there is a function

such that

such that  ,

,

where  is the best payoff for player

is the best payoff for player  given

given  .

.

A simple example

| +1 | –1 | |

| +1 | +b1+w, +b2+w | +b1–w, –b2–w |

| –1 | –b1–w, +b2–w | –b1+w, –b2+w |

| Fig. 1: Potential game example | ||

In a 2-player, 2-strategy game with externalities, individual players' payoffs are given by the function ui(si, sj) = bi si + w si sj, where si is players i's strategy, sj is the opponent's strategy, and w is a positive externality from choosing the same strategy. The strategy choices are +1 and −1, as seen in the payoff matrix in Figure 1.

This game has a potential function P(s1, s2) = b1 s1 + b2 s2 + w s1 s2.

If player 1 moves from −1 to +1, the payoff difference is Δu1 = u1(+1, s2) – u1(–1, s2) = 2 b1 + 2 w s2.

The change in potential is ΔP = P(+1, s2) – P(–1, s2) = (b1 + b2 s2 + w s2) – (–b1 + b2 s2 – w s2) = 2 b1 + 2 w s2 = Δu1.

The solution for player 2 is equivalent. Using numerical values b1 = 2, b2 = −1, w = 3, this example transforms into a simple battle of the sexes, as shown in Figure 2. The game has two pure Nash equilibria, (+1, +1) and (−1, −1). These are also the local maxima of the potential function (Figure 3). The only stochastically stable equilibrium is (+1, +1), the global maximum of the potential function.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

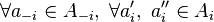

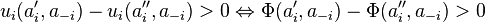

A 2-player, 2-strategy game cannot be a potential game unless

Equilibrium Selection

The existence of pure strategy Nash equilibrium is guaranteed in potential games. There may exist multiple Nash equilibria in potential games. Learning algorithms such as best response, better response can only guarantee that the iterative learning process can converge to one of the Nash equilibra (if multiple). Equilibrium selective learning algorithms aim to design a strategy where convergence to the best Nash equilibrium, with respect to the potential function, is guaranteed. In,[1] the authors propose an equilibrium selective algorithm named MaxLogit, which provably converges to the best Nash equilibrium at the fastest speed in its class, using mixing rate analysis of induced Markovian chains. In a special case where every player shares the same objective function (hence the potential function), and possibly the same action set, the problem is equivalent to distributed combinatorial optimization which arises in many engineering applications. Equilibrium selective learning algorithms such as MaxLogit can be used in such combinatorial optimizations even in a distributed fashion.

References

- ↑ MaxLogit. "Optimal gateway selection in multi-domain wireless networks: a potential game perspective". ACM MOBICOM 2011.

- Dov Monderer and Lloyd S. Shapley: "Potential Games", Games and Economic Behavior 14, pp. 124–143 (1996).

- Emile Aarts and Jan Korst: Simulated Annealing and Boltzmann Machines, John Wiley & Sons (1989) ISBN 0-471-92146-7

External links

- Lecture notes of Yishay Mansour about Potential and congestion games

- Section 19 in: Nisan, N.; Roughgarden, T.; Tardos, É.; Vazirani, V.V. (2007), Algorithmic Game Theory, New York: Cambridge University Press

![[u_{1}(+1,-1)+u_1(-1,+1)]-[u_1(+1,+1)+u_1(-1,-1)] =

[u_{2}(+1,-1)+u_2(-1,+1)]-[u_2(+1,+1)+u_2(-1,-1)]](../I/m/7426ce339e7370a9334502f57794935c.png)