Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome

| Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome | |

|---|---|

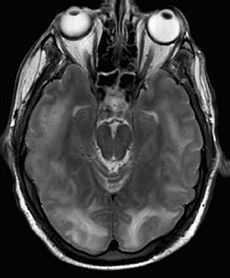

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome visible on magnetic resonance imaging as multiple cortico-subcortical areas of T2-weighted hyperintense (white) signal involving the occipital and parietal lobes bilaterally and pons. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | G93.4 |

| ICD-9 | 348.39 |

| DiseasesDB | 10460 |

| MeSH | D054038 |

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES), also known as reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome (RPLS), is a syndrome characterized by headache, confusion, seizures and visual loss. It may occur due to a number of causes, predominantly malignant hypertension, eclampsia and some medical treatments. On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, areas of edema (swelling) are seen. The symptoms tend to resolve after a period of time, although visual changes sometimes remain.[1][2] It was first described in 1996.[3]

Causes

Several factors appear to play a role in the pathogenesis of PRES, including immunosuppressive therapy, renal failure, eclampsia, severe high blood pressure,[4] and lupus.[5] Low magnesium levels can augment PRES.

Signs and symptoms

Typical symptoms of PRES include headache, nausea, vomiting, altered mental status, seizures, stupor, and visual disturbances.[4] Focal neurologic signs are uncommon in PRES.[4]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is typically made clinically, with supportive findings on magnetic resonance imaging of the brain; this may show hyperintensities on T2-weighed imaging. Three different patterns have been described on MRI imaging.[6] Cerebral angiography may provide a more definite diagnosis.

Treatment

The treatment of PRES depends on the underlying cause. For instance, if the main problem is high blood pressure, blood pressure control will accelerate the resolution of the abnormalities. If the likely cause is medication, the withdrawal of the drug in question is needed.[7]

Prognosis

Many cases resolve within 1–2 weeks of controlling the blood pressure and eliminating the inciting factor. However, long-lasting or even permanent neurologic dysfunction may remain. Though uncommon, death may occur with progressive swelling of the brain (cerebral edema) or a bleed in the brain (intracerebral hemorrhage).

Epidemiology

The incidence of PRES is not currently known. Case reports suggest that there is no age predilection, with cases reported in people ages 2 to 90 years old. It may be somewhat more common in females.

See also

References

- ↑ Garg RK (January 2001). "Posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome". Postgrad Med J 77 (903): 24–8. doi:10.1136/pmj.77.903.24. PMC 1741870. PMID 11123390.

- ↑ Pula JH, Eggenberger E (November 2008). "Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome". Curr Opin Ophthalmol 19 (6): 479–84. doi:10.1097/ICU.0b013e3283129746. PMID 18854692.

- ↑ Hinchey J, Chaves C, Appignani B, Breen J, Pao L, Wang A, Pessin M, Lamy C, Mas J, Caplan L (1996). "A reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome.". N Engl J Med 334 (8): 494–500. doi:10.1056/NEJM199602223340803. PMID 8559202.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Rajasekhar, A.; George, T. J. (November 2007). "Gemcitabine-Induced Reversible Posterior Leukoencephalopathy Syndrome: A Case Report and Review of the Literature". The Oncologist 12 (11): 1332–1335. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.12-11-1332. PMID 18055853.

- ↑ Kur, JK; Esdaile, JM (November 2006). "Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome--an underrecognized manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus.". The Journal of rheumatology 33 (11): 2178–83. PMID 16960925.

- ↑ Peter P, George A. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome and the pediatric population. J Pediatr Neurosci 2012;7:136-8.

- ↑ Pedraza, R; Marik PE; Varon J (November 2009). "Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome: A Review". Critical Care and Shock 12: 135–143.