Pontecorvo–Maki–Nakagawa–Sakata matrix

| Flavour in particle physics |

Flavour quantum numbers:

Related quantum numbers:

Combinations:

|

In particle physics, the Pontecorvo–Maki–Nakagawa–Sakata matrix (PMNS matrix), Maki–Nakagawa–Sakata matrix (MNS matrix), lepton mixing matrix, or neutrino mixing matrix, is a unitary matrix[note 1] which contains information on the mismatch of quantum states of leptons when they propagate freely and when they take part in the weak interactions. It is important in the understanding of neutrino oscillations. This matrix was introduced in 1962 by Ziro Maki, Masami Nakagawa and Shoichi Sakata,[1] to explain the neutrino oscillations predicted by Bruno Pontecorvo.[2][3]

The PMNS matrix

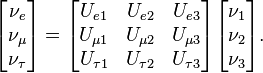

For three generations of leptons, the matrix can be written as:

On the left are the neutrino fields participating in the weak interaction, and on the right is the PMNS matrix along with a vector of the neutrino fields diagonalizing the neutrino mass matrix. The PMNS matrix describes the amplitude that a neutrino of given flavor α will be found in mass eigenstate i. The probability that a neutrino of a given flavor α to be found in mass eigenstate i is proportional to |Uαi|2 (i.e. the square of the magnitude of the amplitude in question).

Due to the difficulties of detecting neutrinos, it is much more difficult to determine the individual coefficients than in the equivalent matrix for the quarks (the CKM matrix).

Assumptions

As noted above, PMNS matrix is unitary (i.e. the sum of the square of the values in each row and in each column, which represent the probabilities of different possible events given the same starting point, add up to 100%) in the simplest Standard Model case in which there are three generations of neutrinos with Dirac mass that oscillate between three neutrino mass eigenvalues, an assumption that is made when best fit values for its parameters are calculated.

The PMNS matrix is not necessarily unitary and additional parameters are necessary to describe all possible neutrino mixing parameters, in other models of neutrino oscillation and mass generation, such as the see-saw model, and in general, in the case of neutrinos that have Majorana mass rather than Dirac mass.

There are also additional mass parameters and mixing angles in a simple extension of the PMNS matrix in which there are more than three flavors of neutrinos, regardless of the character of neutrino mass. As of July 2014, scientists studying neutrino oscillation are actively considering fits of the experimental neutrino oscillation data to an extended PMNS matrix with a fourth, light "sterile" neutrino and four mass eigenvalues, although the current experimental data tends to disfavor that possibility.[4][5][6]

Parameterization

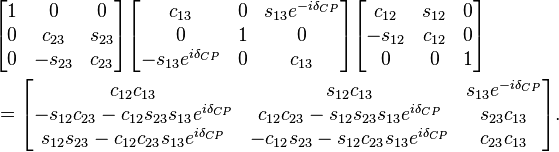

In general, there are nine degrees of freedom in any three by three unitary matrix, and in the PMNS matrix five extra parameters can be absorbed by redefinitions of the complex phase of the Dirac fields, with no change in the observable physics. The matrix can thus be fully described by four free parameters.[7] The PMNS matrix is most commonly parameterized by three mixing angles (θ12, θ23 and θ13) and a single phase called δCP related to charge-parity violations (i.e. differences in the rates of oscillation between two states with opposite starting points which makes the order in time in which events take place necessary to predict their oscillation rates), in which case the matrix can be written as:

where sij and cij are used to denote sinθij and cosθij respectively. In the case of Majorana neutrinos, two extra complex phases are needed, as the phase of Majorana fields cannot be freely redefined due to the condition  . An infinite number of possible parameterizations exist; one other common example being the Wolfenstein parameterization.

. An infinite number of possible parameterizations exist; one other common example being the Wolfenstein parameterization.

The mixing angles have been measured by a variety of experiments (see neutrino mixing for a description). The CP-violating phase δCP has not been measured directly, but estimates can be obtained by fits using the other measurements.

Experimentally measured parameter values

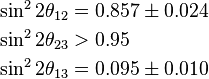

As of July 2014, the current best directly measured values are:[8][9]

while the current best-fit values, using direct and indirect measurements, from NuFit are:[10][11]

Notes regarding the best fit parameter values

- These best fit values imply that there is much more neutrino mixing than there is mixing between the quark flavors in the CKM matrix (in the CKM matrix, the corresponding mixing angles are θ12 = 13.04°±0.05°, θ23 = 2.38°±0.06°, θ13 = 0.201°±0.011°).

- These values are inconsistent with tribimaximal neutrino mixing (i.e. θ12 = θ23 = 45°, θ13 = 0°) at a statistical significance of more than five standard deviations. Tribimaximal neutrino mixing was a common assumption in theoretical physics papers analyzing neutrino oscillation before more precise measurements were available.

- A value of θ23 equal to exactly 45 degrees, which would imply maximal mixing between the second and third neutrino mass eigenstates, is ruled out with a statistical significance in excess of 2 standard deviations.[11]

- The alternative choices for θ23 are referred to as "first quadrant" and "second quadrant" values. The data favor the first quadrant value over the second quadrant value with a statistical significance of 1.5 standard deviations in a "normal mass hierarchy" context (i.e. where the second neutrino mass eigenstate is lighter than the third neutrino mass eigenstate), but there is not a statistically significant preference between the two values in the case of an "inverted mass hierarchy" (i.e. where the second neutrino mass eigenstate is heavier than the third neutrino mass eigenstate).[11] This is the only PMNS matrix parameter which is strongly sensitive to the mass hierarchy of the neutrino masses given the currently available experimental data.[11]

- The extent to which the best fit value for δCP is meaningful should not be overstated. The best fit value for δCP is consistent with zero at the 0.9 standard deviation level, since in circular coordinates 0 degrees and 360 degrees are equivalent. Generally speaking, in particle physics, experimental results that are within 2 standard deviations of each other are called "consistent" with each other. Currently, all possible values for δCP are with 1.8 standard deviations of the best fit values, so all possible values of δCP are "consistent" with the experimental data, even though those values closer to the best fit value are somewhat more likely to be correct.

See also

- Neutrino oscillations

- Koide formula

- Cabibbo–Kobayashi–Maskawa matrix

Notes

- ↑ The PMNS matrix is not unitary in the seesaw model.

References

- ↑ Maki, Z; Nakagawa, M.; Sakata, S. (1962). "Remarks on the Unified Model of Elementary Particles". Progress of Theoretical Physics 28: 870. Bibcode:1962PThPh..28..870M. doi:10.1143/PTP.28.870.

- ↑ Pontecorvo, B. (1957). "Mesonium and anti-mesonium". Zhurnal Éksperimental’noĭ i Teoreticheskoĭ Fiziki 33: 549–551. reproduced and translated in Soviet Physics JETP 6: 429. 1957. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Pontecorvo, B. (1967). "Neutrino Experiments and the Problem of Conservation of Leptonic Charge". Zhurnal Éksperimental’noĭ i Teoreticheskoĭ Fiziki 53: 1717. reproduced and translated in Soviet Physics JETP 26: 984. 1968. Bibcode:1968JETP...26..984P. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Kayser, Boris (February 13, 2014). "Are There Sterile Neutrinos?". arXiv:1402.3028 [hep-ph].

- ↑ Esmaili, Arman; Kemp, Ernesto; Peres, O. L. G.; Tabrizi, Zahra (30 Oct 2013). "Probing light sterile neutrinos in medium baseline reactor experiments". arXiv:1308.6218 [hep-ph].

- ↑ F.P. An, et al.(Daya Bay collaboration) (July 27, 2014). "Search for a Light Sterile Neutrino at Daya Bay". arXiv:1407.7259 [hep-ex].

- ↑ Valle, J. W. F. (2006). "Neutrino physics overview". Journal of Physics: Conference Series 53: 473. arXiv:hep-ph/0608101. Bibcode:2006JPhCS..53..473V. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/53/1/031.

- ↑ J. Beringer et al. (Particle Data Group) (2012 and 2013 partial update for the 2014 edition). "PDGLive: Neutrino Mixing". Particle Data Group. Retrieved 2014-08-21. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ J. Beringer et al. (Particle Data Group) (2012). "Review of Particle Physics". Physical Review D 86: 010001. Bibcode:2012PhRvD..86a0001B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.86.010001.

- ↑ Gonzalez-Garcia, M. C.; Maltoni, M.; Salvado, J.; Schwetz, T. (June 2014). "NuFit 1.3". Retrieved 2014-07-09.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Gonzalez-Garcia, M. C.; Maltoni, Michele; Salvado, Jordi; Schwetz, Thomas (21 December 2012). "Global fit to three neutrino mixing: Critical look at present precision". Journal of High Energy Physics 2012 (12): 123. arXiv:1209.3023. Bibcode:2012JHEP...12..123G. doi:10.1007/JHEP12(2012)123.

![\begin{align}

\theta_{12} [^\circ]& = 33.36^{+0.81}_{-0.78} \\

\theta_{23} [^\circ] & = 40.0^{+2.1}_{-1.5}~\textrm{or}~50.4^{+1.3}_{-1.3} \\

\theta_{13} [^\circ] & = 8.66^{+0.44}_{-0.46} \\

\delta_{\textrm{CP}} [^\circ] & = 300^{+66}_{-138} \\

\end{align}](../I/m/becb7e5522c4e4e5325eb339c5ba4fb6.png)