Poincaré–Lindstedt method

In perturbation theory, the Poincaré–Lindstedt method or Lindstedt–Poincaré method is a technique for uniformly approximating periodic solutions to ordinary differential equations, when regular perturbation approaches fail. The method removes secular terms—terms growing without bound—arising in the straightforward application of perturbation theory to weakly nonlinear problems with finite oscillatory solutions.[1]

The method is named after Henri Poincaré,[2] and Anders Lindstedt.[3]

Example: the Duffing equation

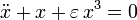

The undamped, unforced Duffing equation is given by

for t > 0, with 0 < ε ≪ 1.[4]

Consider initial conditions

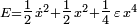

A perturbation-series solution of the form x(t) = x0(t) + ε x1(t) + … is sought. The first two terms of the series are

This approximation grows without bound in time, which is inconsistent with the physical system that the equation models.[5] The term responsible for this unbounded growth, called the secular term, is t sin t. The Poincaré–Lindstedt method allows for the creation of an approximation that is accurate for all time, as follows.

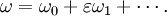

In addition to expressing the solution itself as an asymptotic series, form another series with which to scale time t:

where

where

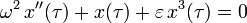

For convenience, take ω0 = 1 because the leading order of the solution's angular frequency is 1. Then the original problem becomes

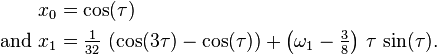

with the same initial conditions. Now search for a solution of the form x(τ) = x0(τ) + ε x1(τ) + … . The following solutions for the zeroth and first order problem in ε are obtained:

So the secular term can be removed through the choice: ω1 = 3⁄8. Higher orders of accuracy can be obtained by continuing the perturbation analysis along this way. As of now, the approximation—correct up to first order in ε—is

References and notes

- ↑ Drazin, P.G. (1992), Nonlinear systems, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-40668-4, pp. 181–186.

- ↑ Poincaré, H. (1957) [1893], Les Méthodes Nouvelles de la Mécanique Célèste II, New York: Dover Publ., §123–§128.

- ↑ A. Lindstedt, Abh. K. Akad. Wiss. St. Petersburg 31, No. 4 (1882)

- ↑ J. David Logan. Applied Mathematics, Second Edition, John Wiley & Sons, 1997. ISBN 0-471-16513-1.

- ↑ The Duffing equation has an invariant energy

= constant, as can be seen by multiplying the Duffing equation with

= constant, as can be seen by multiplying the Duffing equation with  and integrating with respect to time t. For the example considered, from its initial conditions, is found: E = ½ + ¼ ε.

and integrating with respect to time t. For the example considered, from its initial conditions, is found: E = ½ + ¼ ε.

![x(t) = \cos(t) + \varepsilon \left[ \tfrac{1}{32}\, \left( \cos(3t) - \cos(t) \right) - \tfrac{3}{8}\, t\, \sin(t) \right] + \cdots.\,](../I/m/e1adf4989932714cc4fcc632cebe4864.png)

![x(t) \approx \cos\Bigl(\left(1 + \tfrac{3}{8}\, \varepsilon \right)\, t \Bigr)

+ \tfrac{1}{32}\, \varepsilon\, \left[\cos\Bigl( 3 \left(1 + \tfrac{3}{8}\,\varepsilon\, \right)\, t \Bigr)-\cos\Bigl(\left(1 + \tfrac{3}{8}\,\varepsilon\, \right)\, t \Bigr)\right]. \,](../I/m/d167b4a777ef0471397eaaa2b1eb9ade.png)