Plasmodium falciparum biology

| Plasmodium falciparum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Blood smear with Plasmodium falciparum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Chromalveolata |

| Superphylum: | Alveolata |

| Phylum: | Apicomplexa |

| Class: | Aconoidasida |

| Order: | Haemosporida |

| Family: | Plasmodiidae |

| Genus: | Plasmodium |

| Species: | P. falciparum |

| Binomial name | |

| Plasmodium falciparum Welch, 1897 | |

Plasmodium falciparum has been the focus of much research due to it being the causative agent of malaria. This article describes some of the recent findings surrounding the unique biology of this organism.

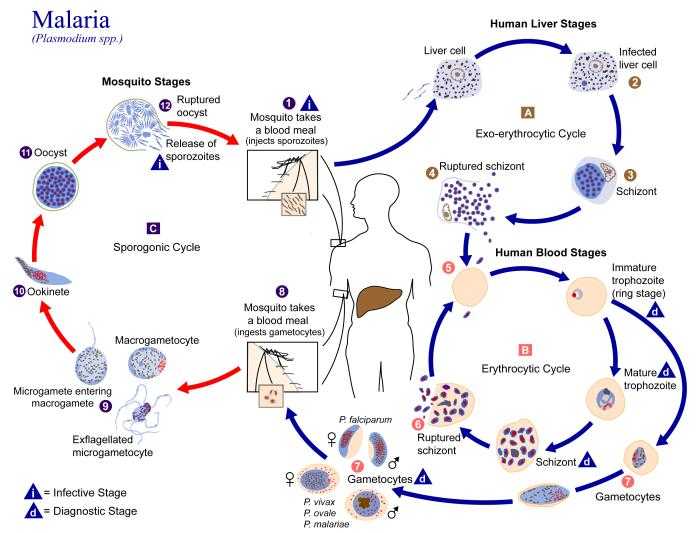

Life Cycle

Plasmodium falciparum has a complicated life-cycle, requiring both a human and a mosquito host, and differentiating multiple times during its transmission/infection process.[1]

Human infection

P. falciparum is transmitted to humans by the females of the Anopheles species of mosquito. There are about 460 species of Anopheles mosquito, but only 68 transmit malaria. Anopheles gambiae is one of the best malaria vectors since it is long-lived, prefers feeding on humans, and lives in areas near human habitation. A. gambiae is found in Africa.[3]

Prior to transmission, Plasmodium falciparum resides within the salivary gland of the mosquito. The parasite is in its sporozoite stage at this point. As the mosquito takes its blood meal, it injects a small amount of saliva into the skin wound. The saliva contains antihemostatic and anti-inflammatory enzymes that disrupt the clotting process and inhibit the pain reaction.[4] Typically, each infected bite contains 5-200 sporozoites which proceed to infect the human.[3] Once in the human bloodstream, the sporozoites only circulate for a matter of minutes before infecting liver cells.

Liver stage

After circulating in the bloodstream, the P. falciparum sporozoites enter hepatocytes. At this point, the parasite loses its apical complex and surface coat, and transforms into a trophozoite. Within the parasitophorous vacuole of the hepatocyte, P. falciparum undergoes schizogonic development. In this stage, nucleus divides multiple times with a concomitant increase in cell size, but without cell segmentation. This exoerythrocytic schizogony stage of P. falciparum has a minimum duration of roughly 5.5 days. After segmentation, the parasite cells are differentiated into merozoites.[5]

After maturation, the merozoites are released from the hepatocytes and enter the erythrocytic portion of their life-cycle. Note that these cells do not reinfect hepatocytes.

Erythrocytic stage

Merozoite

After release from the hepatocytes, the merozoites enter the bloodstream prior to infecting red blood cells. At this point, the merozoites are roughly 1.5 μm in length and 1 μm in diameter, and use the apicomplexan invasion organelles (apical complex, pellicle and surface coat) to recognize and enter the host erythrocyte.

The parasite first binds to the erythrocyte in a random orientation. It then reorients such that the apical complex is in proximity to the erythrocyte membrane. A tight junction is formed between the parasite and erythrocyte. As it enters the red blood cell, the parasite forms a parasitophorous vesicle, to allow for its development inside the erythrocyte.[6]

Trophozoite

After invading the erythrocyte, the parasite loses its specific invasion organelles (apical complex and surface coat) and de-differentiates into a round trophozoite located within a parasitophorous vacuole in the red blood cell cytoplasm. The young trophozoite (or "ring" stage, because of its morphology on stained blood films) grows substantially before undergoing schizogonic division.[7]

Schizont

At the schizont stage, the parasite replicates its DNA multiple times without cellular segmentation. These schizonts then undergo cellular segmentation and differentiation to form roughly 16-18 merozoite cells in the erythrocyte.[7] The merozoites burst from the red blood cell, and proceed to infect other erythrocytes. The parasite is in the bloodstream for roughly 60 seconds before it has entered another erythrocyte.[6]

This infection cycle occurs in a highly synchronous fashion, with roughly all of the parasites throughout the blood in the same stage of development. This precise clocking mechanism has been shown to be dependent on the human host's own circadian rhythm.[8] Specifically, human body temperature changes, as a result of the circadian rhythm, seem to play a role in the development of P. falciparum within the erythrocytic stage.

Within the red blood cell, the parasite metabolism depends greatly on the digestion of hemoglobin.

Infected erythrocytes are often sequestered in various human tissues or organs, such as the heart, liver and brain. This is caused by parasite-derived cell surface proteins being present on the red blood cell membrane, and it is these proteins that bind to receptors on human cells. Sequestration in the brain causes cerebral malaria, a very severe form of the disease, which increases the victim's likelihood of death.

The parasite can also alter the morphology of the red blood cell, causing knobs on the erythrocyte membrane.

Gametocyte differentiation

During the erythrocytic stage, some merozoites develop into male and female gametocytes. This process is called gametocytogenesis.[9] The specific factors and causes underlying this sexual differentiation are largely unknown. These gametocytes take roughly 8–10 days to reach full maturity. Note that the gametocytes remain within the erythrocytes until taken up by the mosquito host.

Mosquito stage

P. falciparum is taken up by the female Anopheles mosquito as it takes its bloodmeal from an infected human.

Gametogenesis

Upon being taken up by the mosquito, the gametocytes leave the erythrocyte shell and differentiate into gametes. The female gamete maturation process entails slight morphological changes, as it becomes enlarged and spherical. On the other hand, the male gamete maturation involves significant morphological development. The male gamete's DNA divides three times to form eight nuclei. Concurrently, eight flagella are formed. Each flagella pairs with a nucleus to form a microgamete, which separates from the parasite cell. This process is referred to as exflagellation.

Gametogenesis has been shown to be caused by: 1) a sudden drop in temperature upon leaving the human host, 2) a rise in pH within the mosquito, and 3) xanthurenic acid within the mosquito.[10] Gametocyte production has been proposed to have an adaptive basis since it increases when conditions for asexual reproduction of the parasite worsen (e.g. upon exposure to immunological stress and/or antimalarial chemotherapy).[11]

Fertilization

During the mosquito blood meal, male and female haploid gametocytes are ingested. Fertilization of the female gamete by the male gamete occurs rapidly after gametogenesis. The fertilization event produces a zygote. The zygote then develops into an ookinete. The zygote and ookinete are the only diploid stages of P. falciparum.

Ookinete

The diploid ookinete is an invasive form of P. falciparum within the mosquito. It traverses the peritrophic membrane of the mosquito midgut and cross the midgut epithelium. Once through the epithelium, the ookinete enters the basil lamina, and forms an oocyst where meiosis takes place.

During the ookinete stage, genetic recombination can occur. This takes place if the ookinete was formed from male and female gametes derived from different populations. This can occur if the human host contained multiple populations of the parasite, or if the mosquito fed from multiple infected individuals within a short time-frame. Because fusion of gametes, zygote formation and meiosis must occur in the mosquito gut for the parasite to complete its life cycle, P.falciparum is an obligate sexual organism.

Sporogony

Over the period of a 1–3 weeks, the oocyst grows to a size of tens to hundreds of micrometres. During this time, multiple nuclear divisions occur. After oocyst maturation is complete, the oocyst divides to form multiple haploid sporozoites. Immature sporozoites break through the oocyst wall into the haemolymph. The sporozoites then migrate to the salivary glands and complete their differentiation. Once mature, the sporozoites can proceed to infect a human host during a subsequent mosquito bite.

Population genetic structure

By studying genetic polymorphisms in the oocysts of mosquitoes in high-infection regions, the population genetic structure of P. falciparum can be determined.[12][13] Razakandrainibe et al.[12] (2007) examined oocysts from Anopheles gambiae mosquito populations in Kenya where malarial transmission is perennial and intense. The oocyts are the only stage of the parasite’s life cycle where diploidy and the immediate products of meiosis can be observed. They found a strong deviation from panmixia (random mating) consistent with a high level of inbreeding of P. falciparum. A contributing factor to this inbreeding was the observed high rate of self-fertilization, about 25% of matings. These findings were confirmed and extended by Annan et al.[13] (2007) who compared two mosquito vectors, Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles funestus, from three widely separated African sites. Thus, despite being an obligate sexual organism, the population structure of P. falciparum appears to predominantly reflect inbreeding.

Cell Biology

Cell Division

Cell division occurs through a process known as schizogony. This is a type of mitotic division in which multiple rounds of nuclear divisions occur before the cytoplasm segments.

Parasitophorous Vacuole

Within a red blood cell, P. falciparum resides inside the parasitophorous vacuole. This is formed during erythrocyte invasion.

The proteins originating in the parasite pass through the membrane of the parasitophorous vacuole, and are transported to the cytoplasm or membrane of the erythrocyte.[14] This transport mechanism is largely unknown.

Apicoplast

Plasmodium falciparum, and other members of the apicomplexa phylum, contain an organelle called the apicoplast.[14] The apicoplast is an essential plastid, homologous to a chloroplast, although the apicoplast is not photosynthetic. Evolutionarily, it is thought to have derived through secondary endosymbiosis.

The function of the apicoplast remains to be fully determined, but it appears to be involved in the metabolism of fatty acids, isoprenoids, and heme.[14]

The apicoplast contains a 35-kb genome, which encodes for 30 proteins. Other, nuclear-encoded, proteins are transported into the apicoplast using a specific signal peptide. It is estimated that 551, or roughly 10%, of the predicted nuclear-encoded proteins are targeted to the apicoplast.[14]

As humans do not harbor apicoplasts, this organelle and its constituents are seen as a possible target for antimalarial drugs.

Genome

The genome of Plasmodium falciparum (clone 3D7) was fully sequenced in 2002.[14] The parasite has a 23 megabase genome, divided into 14 chromosomes.[14] The genome codes for approximately 5,300 genes. About 60% of the putative proteins have little or no similarity to proteins in other organisms, and thus currently have no functional assignment.[14] It is estimated 52.6% of the genome is a coding region, with 53.9% of the putative genes containing at least one intron.[14]

Haploid/Diploid

It is haploid during nearly all stages of its life-cycle, except for a brief period after fertilization when it is diploid from the ookinete to sporogenic stages within the mosquito gut.

AT Richness

The P. falciparum genome has an AT content of roughly 80.6%.[14] Within the intron and intergenic regions, this AT composition rises to roughly 90%. The putative exons contain an AT content of 76.3%. The parasite's AT content is very high in comparison to other organisms. For example, the entire genomes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Arabidopsis thaliana have AT contents of 62% and 65%, respectively.[14]

Subtelomeric regions

The subtelomeric regions of P. falciparum chromosomes show a high degree of conservation within the genome, and contain significant amounts of repeated structure.[14] These conserved regions can be divided into five subtelomeric blocks. The blocks contain tandem repeats in addition to non-repetitive regions.

Many genes involved in antigenic variation are located in the subtelomeric regions of the chromosomes. These are divided into the var, rif, and stevor families. Within the genome, there exist 59 var, 149 rif, and 28 stevor genes, along with multiple pseudogenes and truncations.[14]

Transcriptome

A transcriptome analysis has been conducted on the intraerythrocytic development cycle of P. falciparum.[15] Roughly 60% of the genome is transcriptionally active during this portion of the parasite's life cycle. Whereas many genes appear to have stable mRNA levels throughout the cycle, many of the genes are transcriptionally regulated in a continuous cascade.

The transition from early trophozoite to trophozoite to schizont correlates with the ordered induction of genes related to transcription/translation machinery, metabolic synthesis, energy metabolism, DNA replication, protein degradation, plastid functions, merozoite invasion, and motility.

Closely adjacent genes along the chromosome do not exhibit common transcription characteristics. Thus, genes are likely individually regulated along the parasite chromosome.

Conversely, the apicoplast genome is polycistronic and most of its genes are coexpressed during the intraerythrocytic development cycle.[15]

Proteome

There are 5,268 predicted proteins in Plasmodium falciparum, and roughly 60% share little or no similarity to proteins in other organisms and thus are without functional assignment.[14] Of the predicted proteins, 31% contain at least one transmembrane domain, and 17.3% have a signal peptide or signal anchor.[14]

It is estimated that 10.4% of the proteome is targeted to the apicoplast.[14]

It is estimated that 4.7% of the proteome is targeted to the mitochondria.[14]

The parasite has different subsets of its proteome expressed during various stages of its developmental cycle.[16] In one study, of the 2,415 proteins were identified in four stages(sporozoite, merozoite, trophozoite, gametocyte), representing 46% of the theoretical number of proteins.[16] Only 6% of the proteins were found in all of the four stages. Of the proteins found, 51% were annotated as hypothetical proteins.

Merozoites contained high levels of cell recognition and invasion proteins. Trophozoites contained proteins implicated in erythrocyte remodeling and hemoglobin digestion. Gametocytes contained high amounts of gametocyte-specific transcription factors and cell cycle/DNA processing proteins. The gametocytes had low levels of polymorphic surface antigens. Sporozoites contained large amounts of proteins related to invasion, as well as members of the var and rif families.[16]

Metabolism

While all of the metabolic pathways of Plasmodium falciparum have yet to be fully elucidated, the presence and components of many can be predicted through genomic analysis.[14]

Hemoglobin metabolism

During the erythrocytic stage of the parasite's life cycle, it uses intracellular hemoglobin as a food source. The protein is broken down into peptides, and the heme group is released and detoxified by biocrystallization in the form of hemozoin.

Heme biosynthesis by the parasite has been reported.[17]

Carbohydrate metabolism

During erythrocytic stages, the parasite produces its energy mainly through anaerobic glycolysis, with pyruvate being converted into lactate.[14]

Genes encoding for the TCA cycle enzymes are present in the genome, but it is unclear whether the TCA cycle is used for oxidation of glycolytic products to be used for energy production, or for metabolite intermediate biosynthesis.[14] It has been hypothesized that the main function of the TCA cycle in P. falciparum is for production of succinyl-CoA, to be used in heme biosynthesis.[14]

Genes for nearly all of the pentose phosphate pathway enzymes have been identified from the genome sequence.

Protein metabolism

It has been hypothesized that the parasite obtains all, or nearly all, of its amino acids by salvaging from the host or through the degradation of hemoglobin. This is supported by the fact that genomic analysis has found no enzymes necessary for amino acid biosynthesis, except for glycine-serine, cysteine-alanine, aspartate-asparagine, proline-ornithine, and glutamine-glutamate interconversions.[14]

Nucleotide metabolism

P. falciparum is unable to biosynthesize purines.[14] Instead, the parasite is able to transport and interconvert host purines.

Conversely, the parasite can produce pyrimidines de novo using glutamine, bicarbonate, and aspartate.[14]

Human immune system evasion

var family

The var genes encode for the P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) proteins. The genes are found in the subtelomeric regions of the chromosomes. There exist an estimated 59 var genes within the genome.[14]

The proteins encoded by the var genes are ultimately transported to the erythrocyte membrane and cause the infected erythrocytes to adhere to host endothelial receptors. Due to transcriptional switching between var genes, antigenic variation occurs which enables immune evasion by the parasite.

rif family

The rif genes encode for repetitive interspersed family (rifin) proteins. The genes are found in the subtelomeric regions of the chromosomes. There exist an estimated 149 rif genes within the genome.[14]

Rifin protein are ultimately transported to the erythrocyte membrane. The function of these proteins is currently unknown.

stevor family

The stevor genes encode for the sub-telomeric variable open reading frame (stevor) proteins. The genes are found in the subtelomeric regions of the chromosomes. There exist an estimated 28 stevor genes within the genome.[14]

The function of the stevor proteins is currently unknown.

Research

References

- ↑ Wirth, Dyann (3 October 2002). "The parasite genome: Biological revelations". Nature 419 (6906): 495–496. doi:10.1038/419495a.

- ↑ "DPDx - Malaria Image Library".

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Malaria eModule - Transmission".

- ↑ "Malaria Site: Anopheles Mosquito".

- ↑ "Malaria eModule - Exo-Erythrocytic Stages".

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Cowman (24 February 2006). "Invasion of Red Blood Cells by Malaria Parasites". Cell 124: 755–766. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.006.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Malaria eModule - ASEXUAL ERYTHROCYTIC STAGES".

- ↑ "Malaria eModule - SYNCHRONICITY".

- ↑ "Malaria eModule - GAMETOCYTOGENESIS".

- ↑ Billker (March 19, 1998). "Identification of xanthurenic acid as the putative inducer of malaria development in the mosquito". Nature 392: 289–292. doi:10.1038/32667. PMID 9521324.

- ↑ Buckling AG, Taylor LH, Carlton JM, Read AF (April 1997). "Adaptive changes in Plasmodium transmission strategies following chloroquine chemotherapy". Proc. Biol. Sci. 264 (1381): 553–9. doi:10.1098/rspb.1997.0079. PMC 1688398. PMID 9149425.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Razakandrainibe FG, Durand P, Koella JC, De Meeüs T, Rousset F, Ayala FJ, Renaud F (November 2005). ""Clonal" population structure of the malaria agent Plasmodium falciparum in high-infection regions". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 (48): 17388–93. doi:10.1073/pnas.0508871102. PMC 1297693. PMID 16301534.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Annan Z, Durand P, Ayala FJ, Arnathau C, Awono-Ambene P, Simard F, Razakandrainibe FG, Koella JC, Fontenille D, Renaud F (May 2007). "Population genetic structure of Plasmodium falciparum in the two main African vectors, Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles funestus". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 (19): 7987–92. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702715104. PMC 1876559. PMID 17470800.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 14.7 14.8 14.9 14.10 14.11 14.12 14.13 14.14 14.15 14.16 14.17 14.18 14.19 14.20 14.21 14.22 14.23 14.24 14.25 Gardner, Malcom (3 October 2002). "Genome sequence of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum". Nature 419 (6906): 498–511. doi:10.1038/nature01097. PMID 12368864.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Bozdech, Zbynek (August 18, 2003). "The Transcriptome of the Intraerythrocytic Developmental Cycle of Plasmodium falciparum". PLoS Biology 1 (1): E5. PMC 176545. PMID 12929205.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Florens (3 October 2002). "A proteomic view of the Plasmodium falciparum life cycle". Nature 419 (6906): 520–526. doi:10.1038/nature01107.

- ↑ Bonday, Z.Q. (2002). "Import of host delta-aminolevulinate dehydratase into the malarial parasite: Identification of a new drug target". Nature Medicine 6 (8): 898–903. doi:10.1038/78659.

Additional material

- Jewett , Sibley (2003). "Aldolase forms a bridge between cell surface adhesins and the actin cytoskeleton in apicomplexan parasites". Mol Cell 11 (4): 885–94. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00113-8. PMID 12718875.

|first2=missing|last2=in Authors list (help) - Bergman (2003). "Myosin A tail domain interacting protein (MTIP) localizes to the inner membrane complex of Plasmodium sporozoites". J Cell Sci 116 (1): 39–49. doi:10.1242/jcs.00194.

- Baum (2005). "Invasion by P. falciparum merozoites suggests a hierarchy of molecular interactions". PLoS Pathog 1 (4): e37. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0010037.

|first2=missing|last2=in Authors list (help);|first3=missing|last3=in Authors list (help);|first4=missing|last4=in Authors list (help);|first5=missing|last5=in Authors list (help) - Bosch (2007). "The closed MTIP-myosin A-tail complex from the malaria parasite invasion machinery". J Mol Biol 372 (1): 77–88. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2007.06.016. PMC 2702245. PMID 17628590.

|first2=missing|last2=in Authors list (help);|first3=missing|last3=in Authors list (help);|first4=missing|last4=in Authors list (help);|first5=missing|last5=in Authors list (help);|first6=missing|last6=in Authors list (help) - Bosch (2007). "Aldolase provides an unusual binding site for thrombospondin-related anonymous protein in the invasion machinery of the malaria parasite". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104 (17): 7015–20. doi:10.1073/pnas.0605301104. PMC 1855406. PMID 17426153.

|first2=missing|last2=in Authors list (help);|first3=missing|last3=in Authors list (help);|first4=missing|last4=in Authors list (help);|first5=missing|last5=in Authors list (help);|first6=missing|last6=in Authors list (help);|first7=missing|last7=in Authors list (help);|first8=missing|last8=in Authors list (help);|first9=missing|last9=in Authors list (help) - Daher , Soldati-Favre (2009). "Mechanisms controlling glideosome function in apicomplexans". Cur Opin Micro 12 (4): 408–414. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2009.06.008.

|first2=missing|last2=in Authors list (help) - Sibley (2010). "How apicomplexan parasites move in and out of cells". Cur Opin Biotech 21 (5): 592–598. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2010.05.009.

- Hain and Bosch (2013). "Autophagy in Plasmodium, a multifunctional pathway?". CSBJ 8 (11): 1–9. doi:10.5936/csbj.201308002.

|first2=missing|last2=in Authors list (help) - Boucher and Bosch (2013). "Development of a multifunctional tool for drug screening against plasmodial protein-protein interactions via surface plasmon resonance. |". J. Mol. Recognit. 26 (10): 496–500. doi:10.1002/jmr.2292. PMID 23996492.

|first2=missing|last2=in Authors list (help)

External links

- MR4, The NIAID funded Malaria Research and Reference Reagent Resource Center

- PlasmoDB

- GeneDB

- Malaria IDC Strain Comparison Database

- Malaria IDC Transcriptome Database

- Malaria Parasite Metabolic Pathways

- ApiCyc

- Library of Apicomplexan metabolic pathways

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||