Pisano period

In number theory, the nth Pisano period, written π(n), is the period with which the sequence of Fibonacci numbers, modulo n repeats. For example, the Fibonacci numbers modulo 3 are 0, 1, 1, 2, 0, 2, 2, 1, 0, 1, 1, 2, 0, 2, 2, 1, etc., with the first eight numbers repeating, so π(3) = 8.

Pisano periods are named after Leonardo Pisano, better known as Fibonacci. The existence of periodic functions in Fibonacci numbers was noted by Joseph Louis Lagrange in 1774.[1][2]

Tables

The first Pisano periods (sequence A001175 in OEIS) and their cycles (with spaces before the zeros for readability) are:

| n | π(n) | nr. of 0s | cycle |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 3 | 1 | 011 |

| 3 | 8 | 2 | 0112 0221 |

| 4 | 6 | 1 | 011231 |

| 5 | 20 | 4 | 01123 03314 04432 02241 |

| 6 | 24 | 2 | 011235213415 055431453251 |

| 7 | 16 | 2 | 01123516 06654261 |

| 8 | 12 | 2 | 011235 055271 |

| 9 | 24 | 2 | 011235843718 088764156281 |

| 10 | 60 | 4 | 011235831459437 077415617853819 099875279651673 033695493257291 |

Onward the Pisano periods are 10, 24, 28, 48, 40, 24, 36, 24, 18, 60, 16, 30, 48, 24, 100, 84, 72, 48, 14, 120, 30, 48, 40, 36, 80, 24, 76, 18, 56, 60, 40, 48, 88, 30, 120, 48, 32, 24, 112, 300, ...

For n > 2 the period is even, because alternatingly F(n)2 is one more and one less than F(n − 1)F(n + 1) (Cassini's identity).

The period is relatively small, 4k + 2, for n = F (2k) + F (2k + 2), i.e. Lucas number L (2k + 1), with k a positive integer. This is because F(−2k − 1) = F (2k + 1) and F(−2k) = −F (2k), and the latter is congruent to F(2k + 2) modulo n, showing that the period is a divisor of 4k + 2; the period cannot be 2k + 1 or less because the first 2k + 1 Fibonacci numbers from 0 are less than n.

| k | n | π(n) | first half of cycle (with selected second halves) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 | 6 | 0, 1, 1, 2 (, 3, 1) |

| 2 | 11 | 10 | 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5 (, 8, 2, 10, 1) |

| 3 | 29 | 14 | 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13 (, 21, 5, 26, 2, 28, 1) |

| 4 | 76 | 18 | 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34 (, 55, 13, 68, 5, 73, 2, 75, 1) |

| 5 | 199 | 22 | 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89 (, 144, 34, 178, 13, 191, 5, 196, 2, 198, 1) |

| 6 | 521 | 26 | 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233 |

| 7 | 1364 | 30 | 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377, 610 |

| 8 | 3571 | 34 | 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377, 610, 987, 1597 |

| 9 | 9349 | 38 | 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377, 610, 987, 1597, 2584, 4181 |

The second half of the cycle, which is of course equal to the part on the left of 0, consists of alternatingly numbers F(2m + 1) and n − F(2m), with m decreasing.

Furthermore, the period is 4k for n = F(2k), and 8k + 4 for n = F(2k + 1).

The number of occurrences of 0 per cycle is 1, 2, or 4. Let p be the number after the first 0 after the combination 0, 1. Let the distance between the 0s be q.

- There is one 0 in a cycle, obviously, if p = 1. This is only possible if q is even or n is 1 or 2.

- Otherwise there are two 0s in a cycle if p2 ≡ 1. This is only possible if q is even.

- Otherwise there are four 0s in a cycle. This is the case if q is odd and n is not 1 or 2.

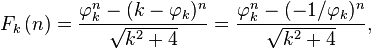

For generalized Fibonacci sequences (satisfying the same recurrence relation, but with other initial values, e.g. the Lucas numbers) the number of occurrences of 0 per cycle is 0, 1, 2, or 4. Also, it can be proven that

- πk(n) ≤ 6n,

with equality if and only if k is odd, k2 + 4 is squarefree, and n = 2 · (k2 + 4)r, for r ≥ 1, the first examples for k = 1 being π1(10) = 60 and π1(50) = 300.

Generalizations

The Pisano periods of Pell numbers (or 2-Fibonacci numbers) are

- 1, 2, 8, 4, 12, 8, 6, 8, 24, 12, 24, 8, 28, 6, 24, 16, 16, 24, 40, 12, 24, 24, 22, 8, 60, 28, 72, 12, 20, 24, 30, 32, 24, 16, 12, 24, 76, 40, 56, 24, 10, 24, 88, 24, 24, 22, 46, 16, 42, 60, ... (sequence A175181 in OEIS)

The Pisano periods of 3-Fibonacci numbers are

- 1, 3, 2, 6, 12, 6, 16, 12, 6, 12, 8, 6, 52, 48, 12, 24, 16, 6, 40, 12, 16, 24, 22, 12, 60, 156, 18, 48, 28, 12, 64, 48, 8, 48, 48, 6, 76, 120, 52, 12, 28, 48, 42, 24, 12, 66, 96, 24, 112, 60, ... (sequence A175182 in OEIS)

The Pisano periods of Jacobsthal numbers (or (1,2)-Fibonacci numbers) are

- 1, 1, 6, 2, 4, 6, 6, 2, 18, 4, 10, 6, 12, 6, 12, 2, 8, 18, 18, 4, 6, 10, 22, 6, 20, 12, 54, 6, 28, 12, 10, 2, 30, 8, 12, 18, 36, 18, 12, 4, 20, 6, 14, 10, 36, 22, 46, 6, 42, 20, ... (sequence A175286 in OEIS)

The Pisano periods of (1,3)-Fibonacci numbers are

- 1, 3, 1, 6, 24, 3, 24, 6, 3, 24, 120, 6, 156, 24, 24, 12, 16, 3, 90, 24, 24, 120, 22, 6, 120, 156, 9, 24, 28, 24, 240, 24, 120, 48, 24, 6, 171, 90, 156, 24, 336, 24, 42, 120, 24, 66, 736, 12, 168, 120, ... (sequence A175291 in OEIS)

The Pisano periods of Tribonacci numbers (or 3-step Fibonacci numbers) are

- 1, 4, 13, 8, 31, 52, 48, 16, 39, 124, 110, 104, 168, 48, 403, 32, 96, 156, 360, 248, 624, 220, 553, 208, 155, 168, 117, 48, 140, 1612, 331, 64, 1430, 96, 1488, 312, 469, 360, 2184, 496, 560, 624, 308, 440, 1209, 2212, 46, 416, 336, 620, ... (sequence A046738 in OEIS)

The Pisano periods of Tetranacci numbers (or 4-step Fibonacci numbers) are

- 1, 5, 26, 10, 312, 130, 342, 20, 78, 1560, 120, 130, 84, 1710, 312, 40, 4912, 390, 6858, 1560, 4446, 120, 12166, 260, 1560, 420, 234, 1710, 280, 1560, 61568, 80, 1560, 24560, 17784, 390, 1368, 34290, 1092, 1560, 240, 22230, 162800, 120, 312, 60830, 103822, 520, 2394, 1560, ... (sequence A106295 in OEIS)

Number theory

Pisano periods can be analyzed using algebraic number theory.

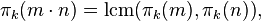

Let  be the n-th Pisano period of the k-Fibonacci sequence Fk(n) ( k can be any natural number, these sequences are defined as Fk(0) = 0, Fk(1) = 1, and for any natural number n > 1, Fk(n) = kFk(n-1) + Fk(n-2)). If m and n are coprime, then

be the n-th Pisano period of the k-Fibonacci sequence Fk(n) ( k can be any natural number, these sequences are defined as Fk(0) = 0, Fk(1) = 1, and for any natural number n > 1, Fk(n) = kFk(n-1) + Fk(n-2)). If m and n are coprime, then  by the Chinese remainder theorem: two numbers are congruent modulo mn if and only if they are congruent modulo m and modulo n, assuming these latter are coprime. For example,

by the Chinese remainder theorem: two numbers are congruent modulo mn if and only if they are congruent modulo m and modulo n, assuming these latter are coprime. For example,  and

and  so

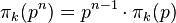

so  Thus it suffices to compute Pisano periods for prime powers

Thus it suffices to compute Pisano periods for prime powers  (Usually,

(Usually,  , unless p is k-Wall-Sun-Sun prime, or k-Fibonacci-Wieferich prime, that is, p2 divides Fk(p-1) or Fk(p+1), where Fk is the k-Fibonacci sequence, for example, 241 is a 3-Wall-Sun-Sun prime, since 2412 divides F3(242).)

, unless p is k-Wall-Sun-Sun prime, or k-Fibonacci-Wieferich prime, that is, p2 divides Fk(p-1) or Fk(p+1), where Fk is the k-Fibonacci sequence, for example, 241 is a 3-Wall-Sun-Sun prime, since 2412 divides F3(242).)

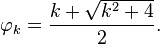

For prime numbers p, these can be analyzed by using Binet's formula:

where

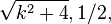

where  is the kth metallic mean

is the kth metallic mean

If k2+4 is a quadratic residue modulo p (and  ), then

), then  and

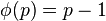

and  can be expressed as integers modulo p, and thus Binet's formula can be expressed over integers modulo p, and thus the Pisano period divides the totient

can be expressed as integers modulo p, and thus Binet's formula can be expressed over integers modulo p, and thus the Pisano period divides the totient  , since any power (such as

, since any power (such as  ) has period dividing

) has period dividing  as this is the order of the group of units modulo p.

as this is the order of the group of units modulo p.

For k = 1, this first occurs for p = 11, where 42 = 16 ≡ 5 (mod 11) and 2 · 6 = 12 ≡ 1 (mod 11) and 4 · 3 = 12 ≡ 1 (mod 11) so 4 = √5, 6 = 1/2 and 1/√5 = 3, yielding φ = (1 + 4) · 6 = 30 ≡ 8 (mod 11) and the congruence

Another example, which shows that the period can properly divide p − 1, is π1(29) = 14.

If k2+4 is not a quadratic residue (and p ≠ 2, and p does not divide the squarefree part of k2+4), then Binet's formula is instead defined over the quadratic extension field (Z/p)[√k^2+4], which has p2 elements and whose group of units thus has order p2 − 1, and thus the Pisano period divides p2 − 1. For example, for p = 3 one has π1(3) = 8 which equals 32 − 1 = 8; for p = 7, one has π1(7) = 16, which properly divides 72 − 1 = 48.

This analysis fails for p = 2 and p is a divisor of the squarefree part of k2+4, since in these cases are zero divisors, so one must be careful in interpreting 1/2 or √k^2+4. For p = 2, k2+4 is congruent to 1 mod 2 (for k odd), but the Pisano period is not p − 1 = 1, but rather 3 (in fact, this is also 3 for even k). For p divides the squarefree part of k2+4, the Pisano period is πk(k2+4) = p2-p = p(p − 1), which does not divide p − 1 or p2 − 1.

For the k-Fibonacci sequence, we should check whether the squarefree part of k2 + 4, or the kth term of this sequence

- 5, 2, 13, 5, 29, 10, 53, 17, 85, 26, 5, 37, 173, 2, 229, 65, 293, 82, 365, 101, 445, 122, 533, 145, 629, 170, 733, 197, 5, 226, 965, 257, 1093, 290, 1229, 13, 1373, 362, 61, 401, 1685, 442, 1853, 485, 2029, 530, 2213, 577, 2405, 626, ... (sequence A013946 in OEIS)

is a quadratic residue mod p or not, if so, the period must divide p − 1, if not, it must divide 2p+2, and this analysis fails for p = 2 or while p divides the k-th term of last sequence.

Sums

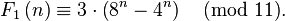

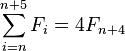

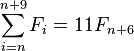

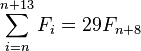

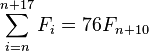

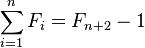

Using:

,

,

it follows that the sum of π(n) consecutive Fibonacci numbers is a multiple of n. Thus:

Moreover, for the examples listed below, the sum of π(n) consecutive Fibonacci numbers is n times the (π(n)/2 + 1)th element:

Powers of 10

The Pisano periods when n is a power of 10 are 60, 300, 1500, 15000, 150000, ... (sequence A096363 in OEIS). Dov Jarden proved that for n greater than 2 the periodicity mod 10n is 15·10n−1.[1]

Cultural references

The Fibonacci sequence modulo 5 (Pisano period 20, with 4 zeros) is featured in the episode "The Case of the Willing Parrot" of the TV series Mathnet, where the sequence is depicted as tiles on a wall.

Fibonacci integer sequences modulo n

One can consider Fibonacci integer sequences and take them modulo n, or put differently, consider Fibonacci sequences in the ring Z/n. The period is a divisor of π(n). The number of occurrences of 0 per cycle is 0, 1, 2, or 4. If n is not a prime the cycles include those that are multiples of the cycles for the divisors. For example, for n = 10 the extra cycles include those for n = 2 multiplied by 5, and for n = 5 multiplied by 2.

Table of the extra cycles:

| n | multiples | other cycles |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||

| 2 | 0 | |

| 3 | 0 | |

| 4 | 0, 022 | 033213 |

| 5 | 0 | 1342 |

| 6 | 0, 0224 0442, 033 | |

| 7 | 0 | 02246325 05531452, 03362134 04415643 |

| 8 | 0, 022462, 044, 066426 | 033617 077653, 134732574372, 145167541563 |

| 9 | 0, 0336 0663 | 022461786527 077538213472, 044832573145 055167426854 |

| 10 | 0, 02246 06628 08864 04482, 055, 2684 | 134718976392 |

References

- Engstrom, H. T. (1931). "On sequences defined by linear recurrence relations". Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 33 (1): 210–218. doi:10.1090/S0002-9947-1931-1501585-5. JSTOR 1989467. MR 1501585.

- Ward, Morgan (1931). "The characteristic number of a sequence of integers satisfying a linear recursion relation". Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 33 (1): 153–165. doi:10.1090/S0002-9947-1931-1501582-X. JSTOR 1989464.

- Ward, Morgan (1933). "The arithmetical theory of linear recurring series". Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 35 (3): 600–628. doi:10.1090/S0002-9947-1933-1501705-4. JSTOR 1989851.

- Zierler, Neal (1959). "Linear recurring sequences". J. SIAM 7 (1): 31–38. doi:10.1137/0107003. JSTOR 2099002. MR 0101979.

- Wall, D. D. (1960). "Fibonacci series modulo m". Am. Math. Monthly 67 (6): 525—532. JSTOR 2309169.

- Bloom, D. M. (1965). "Periodicity in generalized Fibonacci sequences". Am. Math. Monthly 72: 856—861. JSTOR 2315029. MR 0222015.

- Laxton, R. R. (1969). "On groups of linear recurrences". Duke Mathematical Journal 36 (4): 721–736. doi:10.1215/S0012-7094-69-03687-4. MR 0258781.

- Brent, Richard P. (1994). "On the periods of generalized Fibonacci sequences". Mathematics of Computation 63 (207): 389–401. arXiv:1004.5439. Bibcode:1994MaCom..63..389B. JSTOR 2153583. MR 1216256.

- Johnson, R. C. (2008). "Fibonacci numbers and matrices".

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weisstein, Eric W., "Pisano Period", MathWorld.

- ↑ On Arithmetical functions related to the Fibonacci numbers. Acta Arithmetica XVI (1969). Retrieved 22 September 2011.

External links

- Renault, M. S. "The Fibonacci Sequence Modulo m".

- Fibonacci Mystery - Numberphile, a YouTube video with Dr. James Grime and the University of Nottingham

- k-Fibonacci sequence modulo m