Pierrot

Pierrot (French pronunciation: [pjɛʁo]) is a stock character of pantomime and Commedia dell'Arte whose origins are in the late seventeenth-century Italian troupe of players performing in Paris and known as the Comédie-Italienne; the name is a hypocorism of Pierre (Peter), via the suffix -ot. His character in contemporary popular culture—in poetry, fiction, the visual arts, as well as works for the stage, screen, and concert hall—is that of the sad clown, pining for love of Columbine, who usually breaks his heart and leaves him for Harlequin. Performing unmasked, with a whitened face, he wears a loose white blouse with large buttons and wide white pantaloons. Sometimes he appears with a frilled collaret and a hat, usually with a close-fitting crown and wide round brim, more rarely with a conical shape like a dunce's cap. But most frequently, since his reincarnation under Jean-Gaspard Deburau, he wears neither collar nor hat, only a black skullcap. The defining characteristic of Pierrot is his naïveté: he is seen as a fool, often the butt of pranks, yet nonetheless trusting.

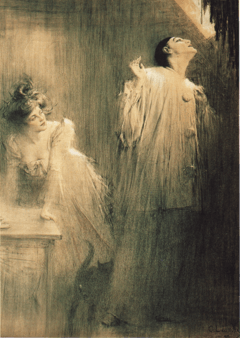

It was a generally buffoonish Pierrot that held the European stage for the first two centuries of his history. And yet early signs of a respectful, even sympathetic attitude toward the character appeared in the plays of Jean-François Regnard and in the paintings of Antoine Watteau, an attitude that would deepen in the nineteenth century, after the Romantics claimed the figure as their own. For Jules Janin and Théophile Gautier, Pierrot was not a fool but an avatar of the post-Revolutionary People, struggling, sometimes tragically, to secure a place in the bourgeois world.[1] And subsequent artistic/cultural movements found him equally amenable to their cause: the Decadents turned him, like themselves, into a disillusioned disciple of Schopenhauer, a foe of Woman and of callow idealism; the Symbolists saw him as a lonely fellow-sufferer, crucified upon the rood of soulful sensitivity, his only friend the distant moon; the Modernists converted him into a Whistlerian subject for canvases devoted to form and color and line.[2] In short, Pierrot became an alter-ego of the artist, specifically of the famously alienated artist of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[3] His physical insularity; his poignant lapses into mutism, the legacy of the great mime Deburau; his white face and costume, suggesting not only innocence but the pallor of the dead; his often frustrated pursuit of Columbine, coupled with his never-to-be vanquished unworldly naïveté—all conspired to lift him out of the circumscribed world of the Commedia dell'Arte and into the larger realm of myth. Much of that mythic quality still adheres to the "sad clown" of the postmodern era.

Origins: seventeenth century

He is sometimes said to be a French variant of the sixteenth-century Italian Pedrolino,[4] but the two types have little but their names ("Little Pete") and social stations in common.[5] Both are comic servants, but Pedrolino, as a so-called first zanni, often acts with cunning and daring,[6] an engine of the plot in the scenarios where he appears.[7] Pierrot, on the other hand, as a "second" zanni, is a static character in his earliest incarnations, "standing on the periphery of the action",[8] dispensing advice that seems to him sage, and courting—unsuccessfully—his master's young daughter, Columbine, with bashfulness and indecision.[9]

His origins among the Italian players in France are most unambiguously traced to Molière's character, the lovelorn peasant Pierrot, in Don Juan, or The Stone Guest (1665).[10] In 1673, probably inspired by Molière's success, the Comédie-Italienne gave a performance of its addendum to the Don Juan legend, Sequel to "The Stone Guest", which included Molière's Pierrot. Thereafter the character—sometimes a peasant,[11] but more often now an Italianate "second" zanni—appeared fairly regularly in the Italians’ offerings, his role always taken by one Giuseppe Giaratone (or Geratoni), until the troupe was banished by royal decree in 1697.

Among the French dramatists who wrote for the Italians and who gave Pierrot life on their stage were Jean Palaprat, Claude-Ignace Brugière de Barante, Antoine Houdar de la Motte, and the most sensitive of his early interpreters, Jean-François Regnard.[12] He acquires there a very distinctive personality. He seems an anomaly among the busy social creatures that surround him; he is isolated, out of touch.[13] Columbine laughs at his advances;[14] his masters who are in pursuit of pretty young wives brush off his warnings to act their age.[15] His is a solitary voice, and his estrangement, however comic, bears the pathos of the portraits—Watteau's chief among them—that we will encounter in the centuries to come.

Eighteenth century

France

An Italian company was called back to Paris in 1716, and Pierrot was reincarnated by the actors Pierre-François Biancolelli (son of the Harlequin of the banished troupe of players) and, after Biancolelli abandoned the role, the celebrated Fabio Sticotti (1676–1741) and his son Antoine-Jean (1715–1772).[16] But the character seems to have been regarded as unimportant by this company, since he appears infrequently in its new plays.[17]

His real life in the theater in the eighteenth century is to be found on the lesser stages of the capital, at its two great fairs, the Foires Saint-Germain and Saint-Laurent. There he appeared in the marionette theaters and in the motley entertainments—featuring song, dance, audience participation, and acrobatics—that were calculated to draw a crowd while sidestepping the regulations that ensured the Théâtre-Français a monopoly on "regular" dramas in Paris.[18] Sometimes he spoke gibberish (in the so-called pièces à la muette); sometimes the audience itself sang his lines, inscribed on placards held aloft by hovering Cupids (in the pièces à écriteau).[19] The result, far from "regular" drama, tended to put a strain on his character, and, as a consequence, the Pierrot of the fairgrounds is a much less nuanced and rounded type than we find in the older repertoire. This holds true even when sophisticated playwrights, such as Alain-René Lesage and his collaborators, Dorneval and Fuzelier, began (around 1712) to contribute more "regular" plays to the Foires.[20]

The broad satirical streak in Lesage often rendered him indifferent to Pierrot's character altogether, and consequently, as the critic Vincent Barberet observes, "Pierrot is assigned the most diverse roles . . . and sometimes the most opposed to his personality. Besides making him a valet, a roasting specialist, a chef, a hash-house cook, an adventurer, [Lesage] just as frequently dresses him up as someone else." In not a few of the early Foire plays, Pierrot's character is therefore "quite badly defined."[21] (For a typical farce by Lesage, see his Harlequin, King of Serendib of 1713.) In the main, Pierrot's years at the Foires were rather degenerate ones.[22]

An important factor that probably hastened this degeneration was the multiplicity of his fairground interpreters. One was the talented actor Jean-Baptiste Hamoche (active 1712–1718, 1721–1732), but there were also acrobats and dancers who appropriated the role, inadvertently reducing Pierrot to a generic type.[23] The extent of that degeneration may be gauged by the fact that Pierrot came to be confused, apparently because of his manner and costume, with that much coarser character Gilles,[24] as a famous portrait by Antoine Watteau attests (see inset).

But the mention of Watteau should also alert us to the fact that Pierrot, along with his fellow Commedia masks,[25] was beginning to be "poeticized" in this century—that he was beginning to be the subject, not only of poignant folksong ("Au clair de la lune", sometimes attributed to Lully), but also of the more ambitious art of Claude Gillot (Master André's Tomb [c. 1717]), of Gillot's students Watteau (Italian Actors [c. 1719]) and Nicolas Lancret (Italian Actors near a Fountain [c. 1719]), of Jean-Baptiste Oudry (Italian Actors in a Park [c. 1725]), and of Jean-Honoré Fragonard (A Boy as Pierrot [1776–1780]). This development will accelerate in the next century.

England

Before turning to that century, however, we should note that it was in this, the eighteenth, that Pierrot began to be naturalized in other countries. As early as 1673, just months after Pierrot had made his debut in the Sequel to "The Stone Guest", Scaramouche Tiberio Fiorilli and a troupe assembled from the Comédie-Italienne entertained Londoners with selections from their Parisian repertoire.[26] And in 1717, Pierrot's name first appears in an English entertainment: a pantomime by John Rich entitled The Jealous Doctor; or, The Intriguing Dame, in which the role was undertaken by a certain Mr. Griffin. Thereafter, until the end of the century, Pierrot appeared fairly regularly in English pantomimes (which were originally mute harlequinades but later evolved into the Christmas pantomimes of today; in the nineteenth century, the harlequinade was presented as a "play within a play" during the pantomime), finding his most notable interpreter in Carlo Delpini (1740–1828). His role was uncomplicated: Delpini, according to the popular theater historian, M. Willson Disher, "kept strictly to the idea of a creature so stupid as to think that if he raised his leg level with his shoulder he could use it as a gun."[27] So conceived, Pierrot was easily and naturally displaced by the native English Clown when the latter found a suitably brilliant interpreter. It did so in 1800, when "Joey" Grimaldi made his celebrated debut in the role.[28]

Denmark

A more long-lasting development occurred in Denmark. In that same year, 1800, a troupe of Italian players led by Pasquale Casorti began giving performances in Dyrehavsbakken, then a well-known site for entertainers, hawkers, and inn-keepers. Casorti's son, Giuseppe (1749–1826), had undoubtedly been impressed by the Pierrots they had seen while touring France in the late eighteenth century, for he assumed the role and began appearing as Pierrot in his own pantomimes, which now had a formulaic structure (Cassander, father of Columbine, and Pierrot, his dim-witted servant, undertake a mad pursuit of Columbine and her rogue lover, Harlequin).[29] The formula has proven enduring: Pierrot is still a fixture at Bakken, the oldest amusement park in the world, where he plays the nitwit talking to and entertaining children, and at nearby Tivoli Gardens, the second oldest, where the Harlequin and Columbine act is performed as a pantomime and ballet. Pierrot—as "Pjerrot", with his boat-like hat and scarlet grin—remains one of the parks’ chief attractions.

Germany

Ludwig Tieck's The Topsy-Turvy World (1798) is an early—and highly successful—example of the introduction of the Commedia dell'Arte characters into parodic metatheater. (Pierrot is a member of the audience watching the play.)

Spain

The penetration of Pierrot and his companions of the Commedia into Spain is documented in a painting by Goya, Itinerant Actors (1793). It foreshadows the work of such Spanish successors as Picasso and Fernand Pelez, who also showed strong sympathy with the lives of traveling saltimbancos.

Nineteenth century

Pantomime of Deburau at the Théâtre des Funambules

When, in 1762, a great fire destroyed the Foire Saint-Germain and the new Comédie-Italienne claimed the fairs’ stage-offerings (now known collectively as the Opéra-Comique) as their own, new enterprises began to attract the Parisian public, as little theaters—all but one now defunct— sprang up along the Boulevard du Temple. One of these was the Théâtre des Funambules, licensed in its early years to present only mimed and acrobatic acts.[30] This will be the home, beginning in 1816, of Jean-Gaspard Deburau (1796–1846),[31] the most famous Pierrot in the history of the theater, immortalized by Jean-Louis Barrault in Marcel Carné's film Children of Paradise (1945).

Adopting the stage-name "Baptiste", Deburau played Pierrot, from about 1819, as the servant of the heavy father (usually Cassander), his mute acting a compound of placid grace and cunning malice. His style, according to Louis Péricaud, the chronicler of the Funambules, formed "an enormous contrast with the exhuberance, the superabundance of gestures, of leaps, that ... his predecessors had employed."[32] He altered the costume: freeing his long neck for comic effects, he dispensed with the frilled collaret; he substituted a skullcap for a hat, thereby keeping his expressive face unshadowed; and he greatly increased the amplitude of both blouse and trousers. Most importantly, the character of his Pierrot, as it evolved gradually through the 1820s, eventually parted company almost completely with the crude Pierrots—timid, sexless, lazy, and greedy—of the earlier pantomime.[33]

With him [wrote the poet and journalist Théophile Gautier after Deburau's death], the role of Pierrot was widened, enlarged. It ended by occupying the entire piece, and, be it said with all the respect due to the memory of the most perfect actor who ever lived, by departing entirely from its origin and being denaturalized. Pierrot, under the flour and blouse of the illustrious Bohemian, assumed the airs of a master and an aplomb unsuited to his character; he gave kicks and no longer received them; Harlequin now scarcely dared brush his shoulders with his bat; Cassander would think twice before boxing his ears.[34]

Deburau seems to have had a predilection for "realistic" pantomime[35]—a predilection that, as we will see, led eventually to calls for Pierrot's expulsion from it. But the pantomime that had the greatest appeal to his public was the "pantomime-arlequinade-féerie", sometimes "in the English style" (i.e., with a prologue in which characters were transformed into the Commedia types). The action unfolded in fairy-land, peopled with good and bad spirits who both advanced and impeded the plot, which was interlarded with comically violent (and often scabrous) mayhem. As in the Bakken pantomimes, that plot hinged upon Cassander's pursuit of Harlequin and Columbine—but it was complicated, in Baptiste's interpretation, by a clever and ambiguous Pierrot. Baptiste's Pierrot was both a fool and no fool; he was Cassandre's valet but no one's servant. He was an embodiment of comic contrasts, showing

imperturbable sang-froid [again the words are Gautier's], artful foolishness and foolish finesse, brazen and naïve gluttony, blustering cowardice, skeptical credulity, scornful servility, preoccupied insouciance, indolent activity, and all those surprising contrasts that must be expressed by a wink of the eye, by a puckering of the mouth, by a knitting of the brow, by a fleeting gesture.[36]

As the Gautier citations suggest, Deburau early—about 1828—caught the attention of the Romantics, and soon he was being celebrated in the reviews of Charles Nodier (Gautier's praise would follow), in an article by Charles Baudelaire on "The Essence of Laughter" (1855), and in the poetry of Théodore de Banville. A pantomime produced at the Funambules in 1828, The Gold Dream, or Harlequin and the Miser, was widely thought to be the work of Nodier, and both Gautier and Banville wrote Pierrot playlets that were eventually produced on other stages—Posthumous Pierrot (1847) and The Kiss (1887), respectively.[37]

"Shakespeare at the Funambules" and aftermath

In 1842, Deburau was inadvertently responsible for translating Pierrot into the realm of tragic myth, heralding the isolated and doomed figure—often the fin-de-siècle artist's alter-ego—of Decadent, Symbolist, and early Modernist art and literature. In that year, Gautier, drawing upon Deburau's newly acquired audacity as a Pierrot, as well as upon the Romantics’ store of Shakespearean plots and of Don-Juanesque legend, published a "review" of a pantomime he claimed to have seen at the Funambules.

He entitled it "Shakespeare at the Funambules", and in it he summarized and analyzed an unnamed pantomime of unusually somber events: Pierrot murders an old-clothes man for garments to court a duchess, then is skewered in turn by the sword with which he stabbed the peddler when the latter's ghost lures him into a dance at his wedding. The pantomime under "review" was a fabrication (though it inspired a hack to turn it into an actual pantomime, The Ol’ Clo's Man [1842], in which Deburau probably appeared[38]—and also inspired Barrault's wonderful recreation of it in Children of Paradise). But it importantly marked a turning-point in Pierrot's career: henceforth Pierrot could bear comparisons with the serious over-reachers of high literature, like Don Juan or Macbeth; he could be a victim—even unto death—of his own cruelty and daring.

When Gustave Courbet drew a crayon illustration for The Black Arm (1856), a pantomime by Fernand Desnoyers written for another mime, Paul Legrand (see next section), the Pierrot who quakes with fear as a black arm snakes up from the ground before him is clearly a child of the Pierrot in The Ol’ Clo's Man. So, too, are Honoré Daumier's Pierrots: creatures often suffering a harrowing anguish.[39] In 1860, Deburau was directly credited with inspiring such anguish, when, in a novella called Pierrot by Henri Rivière, the mime-protagonist blames his real-life murder of a treacherous Harlequin on Baptiste's "sinister" cruelties. Among the most celebrated of pantomimes in the latter part of the century would appear sensitive moon-mad souls duped into criminality—usually by love of a fickle Columbine—and so inevitably marked for destruction (Paul Margueritte's Pierrot, Murderer of His Wife [1881]; the mime Séverin's Poor Pierrot [1891]; Catulle Mendès’ Ol’ Clo's Man [1896], modeled on Gautier's "review").[40]

Pantomime after Baptiste: Charles Deburau, Paul Legrand, and their successors

Deburau's son, Jean-Charles (or, as he preferred, "Charles" [1829–1873]), assumed Pierrot's blouse the year after his father's death, and he was praised for bringing Baptiste's agility to the role.[41] (Nadar's photographs of him in various poses are some of the best to come out of his studio—if not some of the best of the era.)[42]

But the most important Pierrot of mid-century was Charles-Dominique-Martin Legrand, known as Paul Legrand (1816–1898; see photo at top of page). In 1839, Legrand made his debut at the Funambules as the lover Leander in the pantomimes, and when he began appearing as Pierrot, in 1845, he brought a new sensibility to the character. A mime whose talents were dramatic rather than acrobatic, Legrand helped steer the pantomime away from the old fabulous and knockabout world of fairy-land and into the realm of sentimental—often tearful—realism.[43] In this he was abetted by the novelist and journalist Champfleury, who set himself the task, in the 1840s, of writing "realistic" pantomimes.[44] Among the works he produced were Marquis Pierrot (1847), which offers a plausible explanation for Pierrot's powdered face (he begins working-life as a miller's assistant), and the Pantomime of the Attorney (1865), which casts Pierrot in the prosaic role of an attorney's clerk.

Legrand left the Funambules in 1853 for what was to become his chief venue, the Folies-Nouvelles, which attracted the fashionable and artistic set, unlike the Funambules’ working-class children of paradise. Such an audience was not averse to pantomimic experiment, and at mid-century "experiment" very often meant Realism. (The pre-Bovary Gustave Flaubert wrote a pantomime for the Folies-Nouvelles, Pierrot in the Seraglio [1855], which was never produced.)[45] Legrand often appeared in realistic costume, his chalky face his only concession to tradition, leading some advocates of pantomime, like Gautier, to lament that he was betraying the character of the type.[46]

But it was the Pierrot as conceived by Legrand that had the greatest influence on future mimes. Charles himself eventually capitulated: it was he who played the Pierrot of Champfleury's Pantomime of the Attorney. Like Legrand, Charles's student, the Marseilles mime Louis Rouffe (1849–1885), rarely performed in Pierrot's costume, earning him the epithet "l'Homme Blanc" ("The White Man").[47] His successor Séverin (1863–1930) played Pierrot sentimentally, as a doom-laden soul, a figure far removed from the conception of Deburau père.[48] And one of the last great mimes of the century, Georges Wague (1875–1965), though he began his career in Pierrot's costume, ultimately dismissed Baptiste's work as puerile and embryonic, averring that it was time for Pierrot's demise in order to make way for "characters less conventional, more human."[49] Marcel Marceau's Bip seems a natural, if deliberate, outgrowth of these developments, walking, as he does, a concessionary line between the early fantastic domain of Deburau's Pierrot and the so-called realistic world.

Pantomime and late nineteenth-century art

France

- Popular and literary pantomime

In the 1880s and 1890s, the pantomime reached a kind of apogee, and Pierrot became ubiquitous.[50] Moreover, he acquired a counterpart, Pierrette, who rivaled Columbine for his affections. (She seems to have been especially endearing to Xavier Privas, hailed in 1899 as the "prince of songwriters": several of his songs ["Pierrette Is Dead", "Pierrette's Christmas"] are devoted to her fortunes.) A Cercle Funambulesque was founded in 1888, and Pierrot (sometimes played by female mimes, such as Félicia Mallet) dominated its productions until its demise in 1898.[51] Sarah Bernhardt even donned Pierrot's blouse for Jean Richepin's Pierrot the Murderer (1883).

But French mimes and actors were not the only figures responsible for Pierrot's ubiquity: the English Hanlon brothers (sometimes called the Hanlon-Lees), gymnasts and acrobats who had been schooled in the 1860s in pantomimes from Baptiste's repertoire, traveled (and dazzled) the world well into the twentieth century with their pantomimic sketches and extravaganzas featuring riotously nightmarish Pierrots. The Naturalists—Émile Zola especially, who wrote glowingly of them—were captivated by their art.[52] Edmond de Goncourt modeled his acrobat-mimes in his The Zemganno Brothers (1879) upon them; J.-K. Huysmans (whose Against Nature [1884] would become Dorian Gray's bible) and his friend Léon Hennique wrote their pantomime Pierrot the Skeptic (1881) after seeing them perform at the Folies Bergère. (And, in turn, Jules Laforgue wrote his pantomime Pierrot the Cut-Up [Pierrot fumiste, 1882] after reading the scenario by Huysmans and Hennique.)[53] It was in part through the enthusiasm that they excited, coupled with the Impressionists’ taste for popular entertainment, like the circus and the music-hall, as well as the new bohemianism that then reigned in artistic quarters like Montmartre (and which was celebrated by such denizens as Adolphe Willette, whose cartoons and canvases are crowded with Pierrots)—it was through all this that Pierrot achieved almost unprecedented currency and visibility towards the end of the century.

- Visual arts, fiction, poetry, music, and film

He invaded the visual arts[54]—not only in the work of Willette, but also in the illustrations and posters of Jules Chéret;[55] in the engravings of Odilon Redon (The Swamp Flower: A Sad Human Head [1885]); and in the canvases of Georges Seurat (Pierrot with a White Pipe [Aman-Jean] [1883]; The Painter Aman-Jean as Pierrot [1883]), Léon Comerre (Pierrot [1884]), Henri Rousseau (A Carnival Night [1886]), Paul Cézanne (Pierrot and Harlequin [1888]), Fernand Pelez (Grimaces and Miseries a.k.a. The Saltimbanques [1888]), Pablo Picasso (Pierrot and Columbine [1900]), Guillaume Seignac (Pierrot's Embrace [1900]), and Édouard Vuillard (The Black Pierrot [c. 1890]). The mime "Tombre" of Jean Richepin's novel Nice People (Braves Gens [1886]) turned him into a pathetic and alcoholic "phantom"; Paul Verlaine imagined him as a gormandizing naïf in "Pantomime" (1869), then, like Tombre, as a lightning-lit specter in "Pierrot" (1868, pub. 1882).[56] Laforgue put three of the "complaints" of his first published volume of poems (1885) into "Lord" Pierrot's mouth—and dedicated his next book, The Imitation of Our Lady the Moon (1886), completely to Pierrot and his world. (Pierrots were legion among the minor, now-forgotten poets: for samples, see Willette's journal The Pierrot, which appeared between 1888 and 1889, then again in 1891.) In the realm of song, Claude Debussy set both Verlaine's "Pantomime" and Banville's "Pierrot" (1842) to music in 1881 (not published until 1926)—the only precedents among works by major composers being the "Pierrot" section of Telemann's Burlesque Overture (1717–22), Mozart's 1783 "Masquerade" (in which Mozart himself took the role of Harlequin and his brother-in-law, Joseph Lange, that of Pierrot),[57] and the "Pierrot" section of Robert Schumann's Carnival (1835).[58] Even the embryonic art of the motion picture turned to Pierrot before the century was out: he appeared, not only in early celluloid shorts (Georges Méliès's The Nightmare [1896], The Magician [1898]; Alice Guy's Arrival of Pierrette and Pierrot [1900], Pierrette's Amorous Adventures [1900]; Ambroise-François Parnaland's Pierrot's Big Head/Pierrot's Tongue [1900], Pierrot-Drinker [1900]), but also in Emile Reynaud's Praxinoscope production of Poor Pierrot (1892), the first animated movie and the first hand-colored one. (View Poor Pierrot.)

Belgium

Thus far the discussion has focused on the French pierrotistes, but Pierrot's popularity was by no means confined to France. Wherever "decadence" had taken hold, there he could be found.

In Belgium, where the Decadents and Symbolists were as numerous as their French counterparts, Félicien Rops depicted a grinning Pierrot who is witness to an unromantic backstage scene (Blowing Cupid's Nose [1881]) and James Ensor painted Pierrots (and other masks) obsessively, sometimes rendering them prostrate in the ghastly light of dawn (The Strange Masks [1892]), sometimes isolating Pierrot in their midst, his head drooping in despondency (Pierrot's Despair [1892]), sometimes augmenting his company with a smiling, stein-hefting skeleton (Pierrot and Skeleton in Yellow [1893]). Their countryman the poet Albert Giraud also identified intensely with the zanni: the fifty rondels of his Pierrot lunaire (Moonstruck Pierrot [1884]) would inspire several generations of composers (see Pierrot lunaire below), and his verse-play Pierrot-Narcissus (1887) offered a definitive portrait of the solipsistic poet-dreamer. The title of choreographer Joseph Hansen's 1884 ballet, Macabre Pierrot, created in collaboration with the poet Théo Hannon, summed up one of the chief strands of the character's persona for many artists of the era.

England

In the England of the Aesthetic Movement, Aubrey Beardsley's drawings attested profound kinship with the figure; Olive Custance (who would marry Oscar Wilde's lover, Lord Alfred Douglas) published the poem "Pierrot" in 1897; and Ernest Dowson wrote the verse-play Pierrot of the Minute (1897, illustrated by Beardsley), to which the composer Sir Granville Bantock would later contribute an orchestral prologue (1908). One of the gadflies of Aestheticism, W. S. Gilbert, introduced Harlequin and Pierrot as love-struck twin brothers into Eyes and No Eyes, or The Art of Seeing (1875), for which Thomas German Reed wrote the music. And he ensured that neither character, contrary to many an Aesthetic Pierrot, would be amorously disappointed.

In a more bourgeois vein, Ethel Wright painted Bonjour, Pierrot! (a greeting to a dour clown sitting disconsolate with his dog) in 1893. And the Pierrot of popular taste also spawned a uniquely English entertainment. In 1891, the singer and banjoist Clifford Essex returned from France enamored of the Pierrots he had seen there and resolved to create a troupe of English Pierrot entertainers. Thus were born the seaside Pierrots (in conical hats and sometimes black or colored costume) who, as late as the 1950s, sang, danced, juggled, and joked on the piers of Brighton and Margate and Blackpool.[59] Obviously inspired by these troupes were the Will Morris Pierrots, named after their Birmingham founder. They originated in the Smethwick area in the late 1890s and played to large audiences in many parks, theaters, and pubs in the Midlands. It was doubtless these popular entertainers who inspired the academic Walter Westley Russell to commit The Pierrots (c. 1900) to canvas.

Pierrot and Pierrette (1896) was a specimen of early English film from the director Birt Acres. For an account of the English mime troupe The Hanlon Brothers, see France above.

Germany

In Germany, Frank Wedekind introduced the femme-fatale of his first "Lulu" play, Earth Spirit (1895), in a Pierrot costume; and when the Austrian composer Alban Berg drew upon the play for his opera Lulu (unfinished; first perf. 1937), he retained the scene of Lulu's meretricious pierroting. In a similarly (and paradoxically) revealing spirit, the painter Paul Hoecker put cheeky young men into Pierrot costumes to ape their complacent burgher elders, smoking their pipes (Pierrots with Pipes [c. 1900]) and swilling their champagne (Waiting Woman [c. 1895]). (See also Pierrot lunaire below.)

Italy

Canio's Pagliaccio in the famous opera (1892) by Leoncavallo is close enough to a Pierrot to deserve a mention here. Much less well-known is the musical "mimodrama" of Vittorio Monti, Noël de Pierrot a.k.a. A Clown's Christmas (1900), its score set to a pantomime by Fernand Beissier, one of the founders of the Cercle Funambulesque.[60] (Monti would go on to claim his rightful fame by celebrating another spiritual outsider, much akin to Pierrot—the Gypsy. His Csárdás [c. 1904], like Pagliacci, has found a secure place in the standard musical repertoire.)

North America

Pierrot and his fellow masks were late in coming to America, which, unlike England, Russia, and the countries of continental Europe, had had no early exposure to Commedia dell'Arte. The Hanlon-Lees made their first U.S. appearance in 1858, and their subsequent tours, well into the twentieth century, of scores of cities throughout the country accustomed its audiences to their fantastic, acrobatic Pierrots.[61] But the Pierrot that would leave the deepest imprint upon the American imagination was that of the French and English Decadents, a creature who quickly found his home in the so-called little magazines of the 1890s (as well as in the poster-art that they spawned). The earliest and most influential of these, The Chap-Book (1894–98), which featured a story about Pierrot by the aesthete Percival Pollard in its second number,[62] was soon host to Beardsley-inspired Pierrots drawn by E.B. Bird and Frank Hazenplug.[63] (The Canadian poet Bliss Carman should also be mentioned for his contribution to Pierrot's dissemination in mass-market publications like Harper's.)[64] Like most things associated with the Decadence, such exotica discombobulated the mainstream American public, who regarded the little magazines in general as "freak periodicals" and declared, through one of their mouthpieces, Munsey's Magazine, that "each new representative of the species is, if possible, more preposterous than the last."[65]

The fin-de-siècle world in which this Pierrot resided was clearly at odds with the reigning American Realist and Naturalist aesthetic (though such figures as Ambrose Bierce and John LaFarge were mounting serious challenges to it). It is in fact jarring to find the champion of American prose Realism, William Dean Howells, introducing Pastels in Prose (1890), a volume of French prose-poems translated by Stuart Merrill and containing a Paul Margueritte pantomime, The Death of Pierrot, with words of warm praise (and even congratulations to each poet for failing “to saddle his reader with a moral”).[66] So uncustomary was the French Aesthetic viewpoint that, when Pierrot made an appearance in an eponymous pantomime (1893) by Alfred Thompson, set to music by the American composer Laura Sedgwick Collins, The New York Times covered it as an event, even though it was only a student production. It was found to be “pleasing” because, in part, it was “odd”.[67] Not until the first decade of the next century, when the great (and popular) fantasist Maxfield Parrish worked his magic on the figure, would Pierrot be comfortably naturalized in America.

Central and South America

Inspired by the French Symbolists, especially Verlaine, Rubén Darío, the Nicaraguan poet widely acknowledged as the founder of Spanish-American literary Modernism (modernismo), placed Pierrot ("sad poet and dreamer") in opposition to Columbine ("fatal woman", the arch-materialistic "lover of rich silk garments, golden jewelry, pearls and diamonds")[68] in his 1898 prose-poem The Eternal Adventure of Pierrot and Columbine.

Russia

In the last year of the century, Pierrot appeared in a Russian ballet, Harlequin's Millions a.k.a. Harlequinade (1900), its libretto and choreography by Marius Petipa, its music by Riccardo Drigo, its dancers the members of St. Petersburg's Imperial Ballet. It would set the stage for the later and greater triumphs of Pierrot in the productions of the Ballets Russes.

Early twentieth century (1901-1950)

The Pierrot bequeathed to the twentieth century had acquired a rich and wide range of personae. He was the naïve butt of practical jokes and amorous scheming (Gautier); the prankish but innocent waif (Banville, Verlaine, Willette); the narcissistic dreamer clutching at the moon, which could symbolize many things, from spiritual perfection to death (Giraud, Laforgue, Willette, Dowson); the frail, neurasthenic, often doom-ridden soul (Richepin, Beardsley); the clumsy, though ardent, lover, who wins Columbine's heart,[69] or murders her in frustration (Margueritte); the cynical and misogynous dandy, sometimes dressed in black (Huysmans/Hennique, Laforgue); the Christ-like victim of the martyrdom that is Art (Giraud, Willette, Ensor); the androgynous and unholy creature of corruption (Richepin, Wedekind); the madcap master of chaos (the Hanlon-Lees); the purveyor of hearty and wholesome fun (the English pier Pierrots)—and various combinations of these. Like the earlier masks of Commedia dell’Arte, Pierrot now knew no national boundaries. Thanks to the international gregariousness of Modernism, he would soon be found everywhere.[70]

In this section, with the exception of productions by the Ballets Russes (which will be listed alphabetically by title) and of musical settings of Pierrot lunaire (which will be discussed under a separate heading), all works are identified by artist; all artists are grouped by nationality, then listed alphabetically. Multiple works by artists are listed chronologically.

Non-operatic works for stage and screen

Plays, playlets, pantomimes, and revues

- American (U.S.A.)—Clements, Colin Campbell: Pierrot in Paris (1923); Faulkner, William: The Marionettes (1920, pub. 1977); Hughes, Glenn: Pierrot's Mother (1923); Johnstone, Will B.: I'll Say She Is (1924 revue featuring the Marx Brothers and two "breeches" Pierrots; music by Tom Johnstone); Macmillan, Mary Louise: Pan or Pierrot: A Masque (1924); Millay, Edna St. Vincent: Aria da Capo (1920); Renaud, Ralph E.: Pierrot Meets Himself (1933); Rogers, Robert Emmons: Behind a Watteau Picture (1918); Shephard, Esther: Pierrette's Heart (1924); Thompson, Blanche Jennings: The Dream Maker (1922).

- Argentinian—Lugones, Leopoldo: The Black Pierrot (1909).

- Austrian—Noetzel, Hermann: Pierrot's Summer Night (1924); Schnitzler, Arthur: The Transformations of Pierrot (1908), The Veil of Pierrette (1910; with music by Ernö Dohnányi; see also "Stuppner" among the Italian composers under Western classical music (instrumental) below); Schreker, Franz: The Blue Flower, or The Heart of Pierrot: A Tragic Pantomime (1909), The Bird, or Pierrot's Mania: A Pantomimic Comedy (1909).

- Belgian—Cantillon, Arthur: Pierrot before the Seven Doors (1924).

- Brazilian—César da Silva, Júlio: The Death of Pierrot (1915).

- British—Burnaby, Davy: The Co-Optimists (revue of 1921—which was revised continually up to 1926—played in Pierrot costumes, with music and lyrics by various entertainers; filmed in 1929); Cannan, Gilbert: Pierrot in Hospital (1923); "Cryptos" and James T. Tanner: Our Miss Gibbs (1909; musical comedy played in Pierrot costumes); Down, Oliphant: The Maker of Dreams (1912); Drinkwater, John: The Only Legend: A Masque of the Scarlet Pierrot (1913; music by James Brier); Housman, Laurence, and Harley Granville-Barker: Prunella: or, Love in a Dutch Garden (1906, rev. ed. 1911; film of play, directed by Maurice Tourneur, released in 1918); Lyall, Eric: Two Pierrot Plays (1918); Rodker, John: "Fear" (1914), "Twilight I" (1915), "Twilight II" (1915); Sargent, Herbert C.: Pierrot Playlets: Cackle for Concert Parties (1920).

- Canadian—Carman, Bliss, and Mary Perry King Kennerly: Pas de trois (1914); Green, Harry A.: The Death of Pierrot: A Trivial Tragedy (1923); Lockhart, Gene: The Pierrot Players (1918; music by Ernest Seitz).

- Dutch—Nijhoff, Martinus: Pierrot at the Lamppost (1918).

- French—Ballieu, A. Jacques: Pierrot at the Seaside (1905); Beissier, Fernand: Mon Ami Pierrot (1923); Champsaur, Félicien: The Wedding of the Dream (pantomimic interlude in novel Le Combat des sexes [1927]); Guitry, Sacha: Deburau (1918); Hennique, Léon: The Redemption of Pierrot (1903); Morhardt, Mathias: Mon ami Pierrot (1919); Strarbach, Gaston: Pierrot's Revenge (1913); Tervagne, Georges de, and Colette Cariou: Mon ami Pierrot (1945); Voisine, Auguste: Pierrot's Scullery-Brats (1903).

- Italian—Adami, Giuseppe: Pierrot in Love (1924); Cavacchioli, Enrico: Pierrot, Employee of the Lottery: Grotesque Fantasy ... (1920); Zangarini, Carlo: The Divine Pierrot: Modern Tragicomedy ... (1931).

- Japanese—Michio Itō: The Donkey (1918; music by Lassalle Spier).

- Mexican—Rubio, Darío: Pierrot (1909).

- Polish—Leśmian, Boleslaw: Pierrot and Columbine (c. 1910).

- Portuguese—Almada Negreiros, José de: Pierrot and Harlequin (1924).

- Russian—Blok, Alexander: The Fairground Booth a.k.a. The Puppet Show (1906); Evreinov, Nikolai: A Merry Death (1908), Today's Columbine (1915), The Chief Thing (1921; turned into film, La Comédie du bonheur, in 1940).

- Spanish—Aguilar Oliver, Santiago: Gypsy, or Pierrot’s Escapade (n.d.).

Ballet, cabaret, and Pierrot troupes

- Austrian—Rathaus, Karol: The Last Pierrot (1927; ballet).

- British—Gordon, Harry: Scottish entertainer (1893–1957)—formed a Pierrot troupe in 1909 that played both in theaters and at seaside piers in the northeast of Scotland; The Toreadors Concert Party: formed by Charles Elderton at The Theatre Royal in Hebburn, it performed from 1904 in Whitley Bay at what became known, consequently, as Spanish City.

- French—Saint-Saëns, Camille: Pierrot the Astronomer (1907; ballet).

- French/Russian—Productions of the Ballets Russes, under the direction of Sergei Diaghilev:

- Le Carnaval (1910)—music by Robert Schumann (orchestrated by Aleksandr Glazunov, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Anatole Liadov, and Alexander Tcherepnin), choreography by Michel Fokine, set and costumes by Léon Bakst.

- Papillons (Butterflies [1914])—music by Robert Schumann (arranged by Nicolai Tcherepnin), choreography by Michel Fokine, sets by Mstislav Dobuzhinsky, and costumes by Léon Bakst. (This ballet had originally debuted, in 1912, under different directorial auspices, with sets by Piotr Lambine.)

- Parade (1917)—scenario by Jean Cocteau, music by Eric Satie, choreography by Léonide Massine, set and costumes by Pablo Picasso.

- Petrushka (1911)—music by Igor Stravinsky, choreography by Michel Fokine, sets and costumes by Alexandre Benois. (As the Wikipedia article on Petrushka indicates, the Russian clown is in general a Pulcinella figure, but in this ballet he seems closer to a Pierrot.)[71]

- German—Schlemmer, Oskar, and Paul Hindemith: Triadic Ballet (1922).

- Russian—Fokine, Michel: The Immortal Pierrot (1925; ballet, premiered in New York City); Legat, Nikolai and Sergei: The Fairy Doll Pas de trois (1903; ballet; added to production of Josef Bayer's ballet Die Puppenfee in St. Petersburg; music by Riccardo Drigo; revived in 1912 as Les Coquetteries de Columbine, with Anna Pavlova).

- Vertinsky, Alexander: Cabaret singer (1889–1957)—became known as the "Russian Pierrot" after debuting around 1916 with "Pierrot's doleful ditties"—songs that chronicled tragic incidents in the life of Pierrot. Dressed in black, his face powdered white, he performed world-wide, settling for nine years in Paris in 1923 to play the Montmartre cabarets. One of his admirers, Konstantin Sokolsky, assumed his Pierrot persona when he debuted as a singer in 1928.

- See also Pierrot lunaire below.

Films

- American (U.S.A.)—Bradley, Will: Moongold: A Pierrot Pantomime (1921); Browning, Tod: Puppets (1916); Cukor, George: Sylvia Scarlett (1935; features performing foursome called The Pink Pierrots).[72]

- Danish—Schnéevoigt, George: Pierrot Is Crying (1931).

- Dutch—Frenkel, Jr., Theo: The Death of Pierrot (1920); Binger, Maurits: Pierrot's Lie (1922).

- French—Burguet, Paul Henry: The Imprint, or The Red Hand (1908; Gaston Séverin plays Pierrot); Carné, Marcel: Children of Paradise (1945; see above under The Pantomime of Deburau at the Théâtre des Funambules); Carré fils, Michel: The Prodigal Son a.k.a. Pierrot the Prodigal (1907; the first European feature-length film and the first film of a complete stage-play [i.e., Carré's pantomime of 1890]; Georges Wague plays Pierrot père); Feuillade, Louis: Pierrot's Projector (1909), Pierrot, Pierrette (1924); Guitry, Sacha: Deburau (1951; based upon Guitry's own stage-play [see Plays, playlets, pantomimes, and revues above]); Guy, Alice: Pierrot, Murderer (1904); Leprince, René: Pierrot Loves Roses (1910); Méliès, Georges: By Moonlight, or The Unfortunate Pierrot (1904).

- German—Gad, Urban: Behind Comedy's Mask (1913; Pierrot is played by Asta Nielsen); Gottowt, John: The Black Lottery Ticket, or Pierrot's Last Night on the Town (1913); Löwenbein, Richard: Marionettes (1918); Piel, Harry: The Black Pierrot (1913, 1926); Wich, Ludwig von: The Cuckolded Pierrot (1917; view The Cuckolded Pierrot).

- Italian—Alberini, Filoteo: Pierrot in Love (1906); Bacchini, Romolo: Pierrot's Heart (1909); Camagni, Bianca Virginia: Fantasy (1921); Caserini, Mario: A Pierrot's Romance (1906); Falena, Ugo: The Disillusionment of Pierrot (1915); Negroni, Baldassarre: Story of a Pierrot (1913); Notari, Eduardo: So Cries Pierrot (1924).

- Swedish—Lund, Oscar A.C. (worked mainly in U.S.A.): When Pierrot Met Pierrette (1913); Sjöström, Victor (worked mainly in U.S.A.): He Who Gets Slapped (1924; based upon the 1914 play by Leonid Andreyev).

- Ukrainian—Karenne, Diana (worked mainly in Italy, Germany, and France): Pierrot a.k.a. Story of a Pierrot (1917; still from Pierrot).

Visual arts

Works on canvas, paper, and board

- American—Bloch, Albert (worked mainly in Germany as member of Der Blaue Reiter): Many works, including Harlequinade (1911), Piping Pierrot (1911), Harlequin and Pierrot (1913), Three Pierrots and Harlequin (1914); Bradley, Will: Various posters and illustrations (see, e.g., "Banning" under Poetry below); Heintzelman, Arthur William: Pierrot (n.d.); Hopper, Edward: Soir Bleu (1914); Kuhn, Walt: The White Clown (1929); Parrish, Maxfield: Pierrot's Serenade (1908), The Lantern-Bearers (1908), Her Window (1922); Sloan, John: Old Clown Making Up (1910).

- Austrian—Kubin, Alfred: Death of Pierrot (1922); Schiele, Egon: Pierrot (Self-Portrait) (1914).

- Belgian—Ensor, James: Pierrot and Skeletons (1905), Pierrot and Skeletons (1907), Intrigued Masks (1930); Henrion, Armand: Series of self-portraits as Pierrot (1920s).

- Brazilian—Di Cavalcanti: Pierrot (1924).

- British—Knight, Laura: Clown (n.d.); Sickert, Walter: Pierrot and Woman Embracing (1903–1904), Brighton Pierrots (1915; two versions).

- Canadian—Manigault, Middleton (worked mainly in U.S.A.): The Clown (1912), Eyes of Morning (Nymph and Pierrot) (1913).

- Czech—Kubišta, Bohumil: Pierrot (1911).

- Danish—Nielsen, Kay (worked in England 1911-16): Pierrot (c. 1911).

- French—Alleaume, Ludovic: Poor Pierrot (1915); Derain, André: Pierrot (1923–1924), Harlequin and Pierrot (c. 1924); Gabain, Ethel: Many works, including Pierrot (1916), Pierrot's Love-letter (1917), and Unfaithful Pierrot (1919); La Fresnaye, Roger de: Study for "Pierrot" (1921); La Touche, Gaston de: Pierrot's Greeting (n.d.); Laurens, Henri: Pierrot (c. 1922); Matisse, Henri: The Burial of Pierrot (1943); Mossa, Gustav-Adolf: Pierrot and the Chimera (1906), Pierrot Takes His Leave (1906), Pierrot and His Doll (1907); Picabia, Francis: Pierrot (early 1930s); Renoir, Pierre-Auguste: White Pierrot (1901/1902); Rouault, Georges: Many works, including White Pierrot (1911), Pierrot (1920), Pierrot (1937–1938), Pierrot (or Pierrette) (1939), Aristocratic Pierrot (1942), The Wise Pierrot (1943), Blue Pierrots with Bouquet (c. 1946).

- German—Beckmann, Max: Pierrot and Mask (1920), Before the Masked Ball (1922), Carnival (1943); Campendonk, Heinrich: Pierrot with Mask (1916), Pierrot (with Serpent) (1923), Pierrot with Sunflower (1925); Dix, Otto: Masks in Ruins (1946); Faure, Amandus: Standing Artist and Pierrot (1909); Heckel, Erich: Dead Pierrot (1914); Hofer, Karl: Circus Folk (c. 1921), Masquerade a.k.a. Three Masks (1922); Leman, Ulrich: The Juggler (1913); Macke, August: Many works, including Ballets Russes (1912), Clown (Pierrot) (1913), Face of Pierrot (1913), Pierrot and Woman (1913); Mammen, Jeanne: The Death of Pierrot (n.d.); Nolde, Emil: Pierrot and White Lilies (c. 1911), Women and Pierrot (1917); Schlemmer, Oskar: Pierrot and Two Figures (1923); Werner, Theodor: Pierrot lunaire (1942).

- Italian—Modigliani, Amedeo (worked mainly in France): Pierrot (1915); Severini, Gino: Many works, including The Two Pierrots (1922), Pierrot (1923), Pierrot the Musician (1924), The Music Lesson (1928–1929), The Carnival (1955).

- Mexican—Cantú, Federico: Many works, including The Death of Pierrot (1930–1934), Prelude to the Triumph of Death (1934), The Triumph of Death (1939); Montenegro, Roberto: Skull Pierrot (1945); Orozco, José Clemente: The Clowns of War Arguing in Hell (1940s); Zárraga, Ángel: Woman and Puppet (1909).

- Russian—Chagall, Marc (worked mainly in France): Pierrot with Umbrella (1926); Somov, Konstantin: Lady and Pierrot (1910), Curtain Design for Moscow Free Theater (1913), Italian Comedy (1914; two versions); Suhaev, Vasilij, and Alexandre Yakovlev: Harlequin and Pierrot (Self-Portraits of and by Suhaev and A. Yakovlev) (1914); Tchelitchew, Pavel (worked mainly in France and U.S.A.): Pierrot (1930).

- Spanish—Carmona, Fernando Briones: Melancholy Pierrot (1945); Dalí, Salvador: Pierrot with Guitar (1924), Pierrot Playing the Guitar (1925); Gris, Juan (worked mainly in France): Many works, including Pierrot (1919), Pierrot (1921), Pierrot Playing Guitar (1923), Pierrot with Book (1924)—see images at right of page; Picasso, Pablo (worked mainly in France): Many works, including Pierrot (1918), Pierrot and Harlequin (1920), Three Musicians (1921; two versions), Portrait of Adolescent as Pierrot (1922), Paul as Pierrot (1925); Valle, Evaristo: Pierrot (1909).

- Swiss—Klee, Paul (worked mainly in Germany): Many works, including Head of a Young Pierrot (1912), Captive Pierrot (1923), Pierrot Lunaire (1924), Pierrot Penitent (1939).

- Ukrainian—Andriienko-Nechytailo, Mykhailo (worked mainly in France): Pierrot with Heart (1921).

Sculptures and constructions

- American (U.S.A.)—Cornell, Joseph: A Dressing Room for Gilles (1939).

- French—Vermare, André-César: Pierrot (n.d.; terracotta).

- German—Hub, Emil: Pierrot (c. 1920; bronze).

- Lithuanian—Lipchitz, Jacques (worked mainly in France and U.S.A.): Pierrot (1909), Detachable Figure (Pierrot) (1915), Pierrot with Clarinet (1919), Seated Pierrot (1922), Pierrot (1925), Pierrot with Clarinet (1926), Pierrot Escapes (1927).

- Ukrainian—Archipenko, Alexander (worked mainly in France and U.S.A.): Carrousel Pierrot (1913), Pierrot (1942); Ekster, Aleksandra (worked mainly in France): Pierrot (1926).

Literature

Poetry

- American (U.S.A.)—Banning, Kendall: Mon Ami Pierrot: Songs and Fantasies (1917; illustrated by Will Bradley); Beswick, Katherine: Columbine Wonders and Other Poems (c. 1920); Bodenheim, Maxwell: "Pierrot Objects" (1920); Breed, Ida Marian: Poems for Pierrot (1939); Burt, Maxwell Struthers: "Pierrot at War" (1916); Burton, Richard: "Here Lies Pierrot" (1913); Chaplin, Ralph: Maybe, Pierrot ... (c. 1918); Crane, Hart: "The Moth That God Made Blind" (c. 1918, pub. 1966); Crapsey, Adelaide: "Pierrot" (c. 1914); Faulkner, William: Vision in Spring (1921); Ficke, Arthur Davison: "A Watteau Melody" (1913); Garrison, Theodosia: "Good-Bye, Pierrette" (1906), "When Pierrot Passes" (before 1917); Griffith, William: Loves and Losses of Pierrot (1916), Three Poems: Pierrot, the Conjurer, Pierrot Dispossesed [sic], The Stricken Pierrot (1923); Hughes, Langston: "A Black Pierrot" (1923), "Pierrot" (1926), "For Dead Mimes" (1926), "Heart" (1932)—see "Goldweber" under External links below; Loveman, Samuel: "In Pierrot's Garden" (1911; five poems); Lowell, Amy: "Stravinsky's Three Pieces" (1915); Masters, Edgar Lee: "Poor Pierrot" (1918); Moore, Marianne: "To Pierrot Returning to His Orchid" (c. 1910);[73] Shelley, Melvin Geer: "Pierrot" (1940); Stevens, Wallace: "Pierrot" (1909, first pub. 1967 [in Buttel]); Taylor, Dwight: Some Pierrots Come from behind the Moon (1923); Teasdale, Sara: "Pierrot" (1911), "Pierrot's Song" (1915).[74]

- Argentinian—Lugones, Leopoldo: Lunario sentimental (1909).

- Australian—Gard’ner, Dorothy M.: Pierrot and Other Poems (1916).

- Austrian—Schaukal, Richard von: Pierrot and Columbine, or The Marriage Song. A Roundelay ... (1902).

- British—Becker, Charlotte: "Pierrot Goes" (1918); Christie, Agatha: "Pierrot Grown Old" (1925); Drinkwater, John: "Pierrot" (c. 1910); Foss, Kenelm: The Dead Pierrot (1920); Rodker, John: "The Dutch Dolls" (1915).

- Canadian—Carman, Bliss: "At Columbine's Grave" (1902), "The Book of Pierrot", from Poems (1904, 1905).

- Dutch—Nijhoff, Martinus: "Pierrot" (1916).

- Estonian—Semper, Johannes: Pierrot (1917).

- French—Fourest, Georges: "The Blonde Negress" (1909); Klingsor, Tristan: "By Moonlight" (1908), "At the Fountain" (1913); Magre, Maurice: "The Two Pierrots" (1913); Rouault, Georges: Funambules (1926).

- German—Gleichen-Russwurm, Alexander von: Pierrot: A Parable in Seven Songs (1914); Presber, Rudolf: Pierrot: A Songbook (1920).

- Jamaican—Roberts, Walter Adolphe: Pierrot Wounded, Adapted from the French of P. Alberty (1917).

- New Zealander—Hyde, Robin: Series of Pierrette poems (1926–1927).

- Puerto Rican—Blanco, Antonio Nicolás: Pierrot’s Garden (1914).

- Russian—Akhmatova, Anna: Poem without a Hero (Part I: "The Year Nineteen Thirteen", written 1941, pub. 1960); Blok, Alexander: "The Puppet Show", "The Light Wandered about in the Window", "The Puppet Booth", "In the Hour when the Narcissus Flowers Drink Hard", "He Appeared at a Smart Ball", "Double" (1902–1905; series related to Blok's play The Puppet Show [see under Plays, playlets, pantomimes, and revues above]); Guro, Elena: "Boredom" and "Lunar", from The Hurdy-Gurdy (1909); Kuzmin, Mikhail Alekseevich: "Where will I find words" (1906), "In sad and pale make-up" (1912).

- Ukrainian—Semenko, Myhailo: Pierrot Loves (1918), Pierrot Puts on Airs (1918), Pierrot Deadnooses (1919).

Fiction

- American (U.S.A.)—Carryl, Guy Wetmore: "Caffiard, Deus ex Machina" (1902; originally "Pierrot and Pierrette").

- Austrian—Musil, Robert: The Man Without Qualities (1930, 1933, 1943; when main character, Ulrich, meets twin sister, Agatha, for first time after their father's death, they are both dressed as Pierrots).

- British—Ashton, Helen: Pierrot in Town (1913); Barrington, Pamela: White Pierrot (1932); Callaghan, Stella: "Pierrot and the Black Cat" (1921), Pierrot of the World (1923); Deakin, Dorothea: The Poet and the Pierrot (1905); Herring, Paul: The Pierrots on the Pier: A Holiday Entertainment (1914); Priestley, J.B.: The Good Companions (1929; plot follows fortunes of a Pierrot troupe, The Dinky Doos; has had many adaptations, for stage, screen, TV, and radio).

- Czech—Kožík, František: The Greatest of the Pierrots (1939; novel about J.-G. Deburau).

- French—Alain-Fournier: Le Grand Meaulnes a.k.a. The Wanderer (1913; Ganache the Pierrot is an important symbolic figure); Champsaur, Félicien: Lulu (1901),[75] Le Jazz des Masques (1928); Gyp: Mon ami Pierrot (1921); Queneau, Raymond: Pierrot mon ami (1942); Rivollet, Georges: "The Pierrot" (1914).

Music

Songs and song-cycles

- American (U.S.A.)—Goetzl, Anselm: "Pierrot's Serenade" (1915; voice and piano; text by Frederick H. Martens); Johnston, Jesse: "Pierrot: Trio for Women's Voices" (1911; vocal trio and piano); Kern, Jerome: "Poor Pierrot" (1931; voice and orchestra; lyrics by Otto Harbach). For settings of poems by Langston Hughes and Sara Teasdale, see also this note.[74]

- British—Coward, Sir Noël: "Parisian Pierrot" (1922; voice and orchestra); Scott, Cyril: "Pierrot amoureux" (1912; voice and piano), "Pierrot and the Moon Maiden" (1912; voice and piano; text by Ernest Dowson from Pierrot of the Minute [see above under England]); Shaw, Martin: "At Columbine's Grave" (1922; voice and piano; lyrics by Bliss Carman) [see above under Poetry]).

- French—Lannoy, Robert: "Pierrot the Street-Waif" (1938; choir with mixed voices and piano; text by Paul Verlaine); Poulenc, Francis: "Pierrot" (1933; voice and piano; text by Théodore de Banville); Privas, Xavier: Many works, in both Chansons vécues (1903; "Unfaithful Pierrot", "Pierrot Sings", etc.; voice and piano; texts by composer) and Chanson sentimentale (1906; "Pierrot's All Hallows", "Pierrot's Heart", etc.; voice and piano; texts by composer); Rhynal, Camille de: "The Poor Pierrot" (1906; voice and piano; text by R. Roberts).

- German—Künneke, Eduard: [Five] Songs of Pierrot (1911; voice and piano; texts by Arthur Kahane).

- Italian—Bixio, Cesare Andrea: "So Cries Pierrot" (1925; voice and piano; text by composer); Bussotti, Sylvano: "Pierrot" (1949; voice and harp).

- Japanese—Osamu Shimizu: Moonlight and Pierrot Suite (1948/49; male chorus; text by Horiguchi Daigaku).

- See also Pierrot lunaire below.

Instrumental works (solo and ensemble)

- American (U.S.A.)—Abelle, Victor: "Pierrot and Pierrette" (1906; piano); Foote, Arthur: "Pierrot" and "Pierrette", from Five Bagatelles (c. 1894; piano); Hoiby, Lee: "Pierrot" (1950; #2 of Night Songs for voice and piano; text by Adelaide Crapsey [see above under Poetry]); Neidlinger, William Harold: Piano Sketches (1905; #5: "Pierrot"; #7: "Columbine"); Oehmler, Leo: "Pierrot and Pierrette – Petite Gavotte" (1905; violin and piano).

- Belgian—Strens, Jules: "Mon ami Pierrot" (1926; piano).

- British—Scott, Cyril: "Two Pierrot Pieces" (1904; piano), "Pierrette" (1912; piano).

- Brazilian—Nazareth, Ernesto: "Pierrot" (1915; piano: Brazilian tango).

- Czech—Martinů, Bohuslav: "Pierrot's Serenade", from Marionettes, III (c. 1913, pub. 1923; piano).

- French—Debussy, Claude: Sonata for Cello and Piano (1915; Debussy had considered calling it "Pierrot angry at the moon"); Popy, Francis: Pierrot Sleeps (n.d.; violin and piano); Salzedo, Carlos (worked mainly in U.S.A.): "Pierrot is Sad", from Sketches for Harpist Beginners, two series (1942; harp); Satie, Erik: "Pierrot's Dinner" (1909; piano).

- German—Kaun, Hugo: Pierrot and Columbine: Four Episodes (1907; piano).

- Hungarian—Vecsey, Franz von: "Pierrot's Grief" (1933; violin and piano).

- Italian—Drigo, Riccardo (worked mainly in Russia): "Pierrot's Song: Chanson-Serenade for Piano" (1922); Pierrot and Columbine" (1929; violin and piano). These pieces are re-workings of the famous "Serenade" from his score for the ballet Les Millions d'Arlequin (see Russia above).

- Swiss—Bachmann, Alberto: Children's Scenes (1906; #2: "Little Pierrot"; violin and piano).

Works for orchestra

- American (U.S.A.)—Thompson, Randall: Pierrot and Cothurnus (1922; prelude to Edna St. Vincent Millay's Aria da Capo [see under Plays, Playlets, and Pantomimes above]).

- Austrian—Zeisl, Erich: Pierrot in the Bottle: Ballet-Suite (1935; ballet itself [1929] remains unperf.).

- British—Bantock, Sir Granville: Pierrot of the Minute: Overture to a Dramatic Fantasy of Ernest Dowson (1908; see under England above); Holbrooke, Joseph Charles: Ballet Suite #1, "Pierrot", for String and Full Orchestra (1909).

- French—Popy, Francis: Pierrot’s Secret (n.d.; overture).

- German—Reger, Max: A Ballet-Suite for Orchestra (1913; #4: "Pierrot and Pierrette").

- Hungarian—Lehár, Franz: "Pierrot and Pierrette" (1911; waltz).

- Italian—Masetti, Enzo: Contrasts (1927; part 1: "Pierrot's Night").

- Russian—Pingoud, Ernest (worked mainly in Finland): Pierrot's Last Adventure (1916).

Operas, operettas, and zarzuelas

- American (U.S.A.)—Barlow II, Samuel Latham Mitchell: Mon Ami Pierrot (1934; libretto by Sacha Guitry).

- Austrian—Berg, Alban: Lulu (unfinished; first perf. 1937; libretto by composer, adapted from "Lulu" plays of Frank Wedekind [see under Germany above]); Korngold, Erich Wolfgang: Die tote Stadt (The Dead City [1920]; libretto by composer and Paul Schott; actor Fritz banters and sings in the guise and costume of Pierrot—an ironic counterpart to the lovelorn main character, Paul).

- Belgian—Dell'Acqua, Eva: Pierrot the Liar (1918); Renieu, Lionel: The Chimera, or Pierrot the Alchemist (1926; libretto by Albert Nouveau and Fortuné Paillot).

- British—Holbrooke, Joseph Charles: Pierrot and Pierrette (1909; libretto by Walter E. Grogan).

- German—Goetze, Walter: The Golden Pierrot (1934; libretto by Oskar Felix and Otto Kleinert).

- Hungarian—Lehér, Franz: The Count from Luxembourg (1909; libretto by A. M. Willner, Robert Bodanzky, and Leo Stein; with roles for Pierrot and Pierrette).

- Italian—Menotti, Gian Carlo: The Death of Pierrot (1923; written by Menotti, including libretto, when he was age 11, in the same year he entered the Milan Conservatory for formal training).

- Spanish—Barrera Saavedra, Tomás: Pierrot's Dream (1914; libretto by Luis Pascual Frutos); Chapí, Ruperto: The Tragedy of Pierrot (1904; libretto by Ramón Asensio Más and José Juan Cadenas).

Late twentieth/early twenty-first centuries (1951- )

In the latter half of the twentieth century, Pierrot continued to appear in the art of the Modernists—or at least of the long-lived among them: Chagall, Ernst, Goleminov, Hopper, Miró, Picasso—as well as in the work of their younger followers, such as Gerard Dillon, Indrek Hirv, and Roger Redgate. And when film arrived at a pinnacle of auteurism in the 1950s and '60s, aligning it with the earlier Modernist aesthetic, some of its most celebrated directors—Bergman, Fellini, Godard—turned naturally to Pierrot.

But Pierrot's most prominent place in the late twentieth century, as well as in the early twenty-first, has been in popular, not High Modernist, art. As the entries below tend to testify, Pierrot is most visible (as in the eighteenth century) in unapologetically popular genres—in circus acts and street-mime sketches, TV programs and Japanese anime, comic books and graphic novels, children's books and "young adult" fiction (especially fantasy and, in particular, vampire fiction), Hollywood films, and pop and rock music. He generally assumes one of three avatars: the sweet and innocent child (as in the children's books), the poignantly lovelorn and ineffectual being (as, notably, in the Jerry Cornelius novels of Michael Moorcock), or the somewhat sinister and depraved outsider (as in David Bowie's various experiments, or Rachel Caine's vampire novels, or the S&M lyrics of the English rock group Placebo).

The format of the lists that follow is the same as that of the previous section, except for the Western pop-music singers and groups. These are listed alphabetically by first name, not last (e.g., "Stevie Wonder", not "Wonder, Stevie").

Non-operatic works for stage and screen

Plays, pantomimes, variety shows, circus, and dance

- American—Balanchine, George (born in Russia): Harlequin (1965; revival of ballet Harlequin's Millions [see Russia above]); Craton, John: Pierrot and Pierrette a.k.a. Le Mime solitaire (2009; ballet); Muller, Jennifer (head of three-member Works Dance Company, New York): Pierrot (1986; music and scenario by Thea Musgrave [see below under Western classical: Instrumental]); Russillo, Joseph (works mainly in France): Pierrot (1975; ballet).

- British—Littlewood, Joan, and the Theatre Workshop: Oh, What a Lovely War! (1963; a musical satire on World War I played in Pierrot costumes); Wilson, Ronald Smith: Harlequin, Pierrot & Co. (1976).

- Canadian—Cirque du Soleil (performs internationally): Corteo (2005–present; It. cortéo = "cortège" or "funeral procession"; Pierrot appears as "White Clown"), La Nouba (1998–present; as in "faire la nouba", i.e., "to party"; features a Pierrot Rouge [or "Acrobatic Pierrot"] and a Pierrot Clown).

- Cuban—Morejón, Nancy: Pierrot and the Moon (1999).

- French—Baival, C., Paul Ternoise, and Albert Verse: Pierrot's Choice (1950); Marceau, Marcel: Pierrot of Montmartre (1952; music by Joseph Kosma); The Mime Sime: The Fantasies of Pierrot (2007); Prévert, Jacques: Baptiste (1959; choreography by Jean-Louis Barrault).

- German—König, Rainer: Pierrot's Version: A Mime Breaks His Silence (n.d.); Lemke, Joachim: Pierrot for a Moment (n.d.); Mr Pustra (performs internationally): self-styled "Vaudeville's Darkest Muse" (2009-present).

- Russian—Pimonenko, Evgeny (performs internationally): Your Pierrot (c. 1994–present; act by black-suited Pierrot-juggler-equilibrist, originally of Valentin Gneushev's Cirk Valentin).

- Swedish—Cramér, Ivo: Pierrot in the Dark (1982; ballet).

- Swiss—Pic (Richard Hirzel): Pierrot clown famously associated, from 1980, with the German Circus Roncalli.

- See also Pierrot lunaire below.

Films, television, and anime

- American—Anger, Kenneth: Rabbit's Moon (1950 film released in 1972, revised 1979); Irwin, Bill: The Circus (1990; TV movie; based on short story by Katherine Anne Porter); Kelly, Gene: Invitation to the Dance (1956 film; Kelly appears as Pierrot in opening ["Circus"] segment); Wise, Robert: Star! (1968 film; main character Gertrude Lawrence, played by Julie Andrews, dressed as Pierrot, sings Noël Coward's "Parisian Pierrot"—as Lawrence herself did in Coward's review London Calling! [1923], for which the song was written).

- British—Graham, Matthew, and Ashley Pharaoh: Ashes to Ashes (2008 TV series; main character, Alex Drake, is haunted by Pierrot like that in David Bowie video Ashes to Ashes); Mahoney, Brian: Pierrot in Turquoise or The Looking Glass Murders (1970 film written and performed by David Bowie and Lindsay Kemp, adapted from their stage-play of the same title [1967] and produced by Scottish Television [see also Songs, albums, and rock musicals below]).

- Canadian/German—LaBruce, Bruce: Pierrot Lunaire (2014 fillm).

- French—Albicocco, Jean-Gabriel: Le Grand Meaulnes a.k.a. The Wanderer (1967 film; based upon the Alain-Fournier novel [see above under Fiction]); Godard, Jean-Luc: Pierrot le fou (Pierrot the Fool [1965 film]).

- Italian—Cavani, Liliana: The Night Porter (1974 film; Pierrot motifs are abundant—from the Nazi ballet-dancer Bert, who assumes the role of a Pierrot-like character [pale, effeminate, occasionally seen either in a white shirt or in a black cap], to the characters in the singing scene, some of which [both Nazis and prisoners] wear frilled collars or white masks); Fellini, Federico: The Clowns (1970 film).

- Japanese—Shinichiro Watanabe: Cowboy Bebop (1998 anime; twentieth episode, “Pierrot le fou”, references both the character and the Godard film [see above, this section, under French]). See also "Japanese (manga)" under Comic books.

- Swedish—Bergman, Ingmar: In the Presence of a Clown (1997 film for TV; the Pierrot-like—yet female—Rigmor, the clown of the title, is an important symbolic figure).

Visual arts

- American (U.S.A.)—Dellosso, Gabriela Gonzalez: Many works, most notably Garrik (n.d.); Hopper, Edward: Two Comedians (1966); Longo, Robert: Pressure (1982/83); Nauman, Bruce: No No New Museum (1987; videotape); Serrano, Andres: A History of Sex (Head) (1996).

- Argentinian—Ortolan, Marco: Venetian Clown (n.d.); Soldi, Raúl: Pierrot (1969), Three Pierrots (n.d.).

- Austrian—Absolon, Kurt: Cycle of Pierrot works (1951).

- British—Hockney, David: Troop of Actors and Acrobats (1980; one of stage designs for Satie's Parade [see under Ballet, cabaret, and Pierrot troupes above]), paintings on Munich museum walls for group exhibition on Pierrot (1995); Self, Colin: Pierrot Blowing Dandelion Clock (1997).

- Chilean—Bravo, Claudio: The Ladies and the Pierrot (1963).

- Colombian—Botero, Fernando: Pierrot (2007), Pierrot lunaire (2007), Blue Pierrot (2007), White Pierrot (2008).

- German—Alt, Otmar: Pierrot (n.d.).; Ernst, Max (worked mainly in France): Mon ami Pierrot (1974); Lüpertz, Markus: Pierrot lunaire: Chair (1984).

- Irish—Dillon, Gerard: Many works, including Bird and Bird Canvas (c. 1958), And the Time Passes (1962), The Brothers (1967), Beginnings (1968), Encounter (c. 1968), Red Nude with Loving Pierrot (c. 1970); Robinson, Markey: Many works.

- Russian—Chagall, Marc (worked mainly in France): Circus Scene (late 1960s/early 1970s), Pierrot lunaire (1969).

- Spanish—Miró, Joan (worked mainly in France and U.S.A.): Pierrot le fou (1964); Picasso, Pablo (worked mainly in France): Many works, including Pierrot with Newspaper and Bird (1969), various versions of Pierrot and Harlequin (1970, 1971), and metal cut-outs: Head of Pierrot (c. 1961), Pierrot (1961); Roig, Bernardí: Pierrot le fou (2009; polyester and neon lighting); Ruiz-Pipó, Manolo: Many works, including Orlando (Young Pierrot) (1978), Pierrot Lunaire (n.d.), Lunar Poem (n.d.).

- Commercial art. A variety of Pierrot-themed items, including figurines, jewelry, posters, and bedclothes, are sold commercially.[76]

Literature

Poetry

- American (U.S.A.)—Hecht, Anthony: "Clair de lune" (before 1977); Koestenbaum, Wayne: Pierrot Lunaire (2006; ten original poems with titles from the Giraud/Schoenberg cycle in Koestenbaum's Best-Selling Jewish Porn Films [2006]); Nyhart, Nina: "Captive Pierrot" (1988; after the Paul Klee painting [see above under Works on Canvas, Paper and Board]); Peachum, Jack: "Our Pierrot in Autumn" (2008).

- British—Moorcock, Michael: "Pierrot on the Moon" (1987); Smart, Harry: "The Pierrot" (1991).

- Estonian—Hirv, Indrek: The Star Beggar (1993).

- French—Butor, Michel and Michel Launay: Pierrot Lunaire (1982; retranslation into French of Hartleben's 21 poems used by Schoenberg [see Pierrot lunaire below], followed by original poems by Butor and Launay).

- Italian—Brancaccio, Carmine: The Pierrot Quatrains (2007).

- New Zealander—Sharp, Iain: The Pierrot Variations (1985).

Fiction

- American (U.S.A.)—Caine, Rachel: Feast of Fools (Morganville Vampires, Book 4) (2008; vampire Myrnin dresses as Pierrot); Dennison, George: "A Tale of Pierrot" (1987); DePaola, Tomie: Sing, Pierrot, Sing: A Picture Book in Mime (1983; children's book, illustrated by the author); Hoban, Russell (has lived in England since 1969): Crocodile and Pierrot: A See-the-Story Book (1975; children's book, illustrated by Sylvie Selig).

- Austrian—Frischmuth, Barbara: ‘’From the Life of Pierrot’’ (1982).

- Belgian—Norac, Carl: Pierrot d'amour (2002; children's book, illustrated by Jean-Luc Englebert).

- Brazilian—Antunes, Ana Claudia: The Pierrot's Love (2009).

- British—Gaiman, Neil (has lived in U.S.A. since 1992): "Harlequin Valentine" (1999), Harlequin Valentine (2001; graphic novel, illustrated by John Bolton); Greenland, Colin: "A Passion for Lord Pierrot" (1990); Moorcock, Michael: The English Assassin and The Condition of Muzak (1972, 1977; hero Jerry Cornelius morphs with increasing frequency into role of Pierrot), "Feu Pierrot" (1978); Stevenson, Helen: Pierrot Lunaire (1995).

- Canadian—Major, Henriette: The Vampire and the Pierrot (2000; children's book); Laurent McAllister: "Le Pierrot diffracté" ("The Diffracted Pierrot" [1992]).

- French—Boutet, Gérard: Pierrot and the Secret of the Flint Stones (1999; children's book, illustrated by Jean-Claude Pertuzé); Dodé, Antoine: Pierrot Lunaire (2011; vol. 1 of projected graphic-novel trilogy, images by the author); Tournier, Michel: "Pierrot, or The Secrets of the Night" (1978).

- Japanese—Kōtaro Isaka: A Pierrot a.k.a. Gravity Clown (2003; a film based on the novel was released in 2009).

- Polish—Lobel, Anita (naturalized U.S. citizen 1956): Pierrot's ABC Garden (1992; children's book, illustrated by author).

- Russian—Baranov, Dimitri: Black Pierrot (1991).

- South Korean—Jung Young-moon: Moon-sick Pierrot (2013).

Comic books

- American (U.S.A.)—DC Comics: Batman R.I.P.: Midnight in the House of Hurt (2008 [#676]; features Pierrot Lunaire, who will appear in eight more issues).

- Japanese (manga)—Katsura Hoshino: D. Gray-man, serialized in Weekly Shōnen Jump and Jump Square (2004–present; main character, Allen Walker, is "the pierrot who will cause the akuma [i.e, demons] to fall"; anime based on manga released 2006–2008); Takashi Hashiguchi: Yakitate!! Japan (Freshly Baked!! Japan [Jap. pan = bread]), serialized in Shogakukan's Shōnen Sunday (2002–2007; features a clown-character named Pierrot Bolneze, heir to the throne of Monaco; anime based on manga released 2004–2006).

Music

Western classical

- Vocal

- American (U.S.A.)—Austin, Larry: Variations: Beyond Pierrot (1995; voice, small ensemble, live computer-processed sound, and computer-processed prerecorded tape); Fairouz, Mohammed: Pierrot Lunaire (2013; tenor and Pierrot ensemble; texts by Wayne Koestenbaum [see above under Poetry]); Schachter, Michael: "Pierrot (Heart)" (2011; voice and piano; text by Langston Hughes [see above under Poetry]).

- British—Christie, Michael: "Pierrot" (1998; voice and small ensemble; text by John Drinkwater [see above under Poetry]); St. Johanser, Joe: "Pierrot" (2003; from song-cycle Pierrot Alone; voice and chamber orchestra; text by John Drinkwater [see above under Poetry]).

- Polish—Szczeniowski, Boleslaw (worked mainly in Canada): "Pierrot" (1958; voice; text by Wilfrid Lemoine).

- Japanese—Norio Suzuki: "Pierrot Clown" (1995; women's chorus).

- Instrumental

- American (U.S.A.)—Brown, Earle: Tracking Pierrot (1992; chamber ensemble); Wharton, Geoffry (works mainly in Germany): ‘’Five Pierrot Tangos’’ (n.d.; violin/viola, flute, piano/synthesizer, cello, clarinet, and voice).

- Argentinian—Franzetti, Carlos: Pierrot and Columbine (2012; small ensemble and string orchestra).

- Austrian—Herf, Franz Richter: "Pierrot" (1955; piano).

- British—Beamish, Sally: Commedia (1990; mixed quintet; theater piece without actors, in which Pierrot is portrayed by violin); Biberian, Gilbert: Variations and Fugue on "Au Clair de la Lune" (1967; wind quartet), Pierrot: A Ballet (1978; guitar duo); Musgrave, Thea, Pierrot (1985; for clarinet [Columbine], violin [Pierrot], and piano [Harlequin]; inspired dance by Jennifer Muller [see above under Plays, variety shows, circus, and dance]); Redgate, Roger: Pierrot on the Stage of Desire (1998; for Pierrot ensemble).

- Bulgarian—Goleminov, Marin: "Pierrot", from Five Impressions (1959; piano).

- Canadian—Longtin, Michel: The Death of Pierrot (1972; tape-recorder).

- Dutch—Boer, Eduard de (a.k.a. Alexander Comitas): Pierrot: Scherzo for String Orchestra (1992).

- Finnish—Tuomela, Tapio: Pierrot: Quintet No. 2 for Flute, Clarinet, Violin, Cello, and Piano (2004).

- French—Duhamel, Antoine: Pierrot le fou: Four Pieces for Orchestra (1965/66); Françaix, Jean: Pierrot, or The Secrets of the Night (1980; ballet, libretto by Michel Tournier; see above under Fiction); Lancen, Serge: Masquerade: For Brass Quintet and Wind Orchestra (1986; #3: "Pierrot"); Naulais, Jérôme: The Moods of Pierrot (n.d.; flute and piano).

- German—Kirchner, Volker David: Pierrot's Gallows Songs (2001; clarinet); Kühmstedt, Paul: Dance-Visions: Burlesque Suite (1978; #3: "Pierrot and Pierrette").

- Hungarian—Papp, Lajos: Pierrot Dreams: Four Pieces for Accordion (1993).

- Italian—Guarnieri, Adriano: Pierrot Suite (1980; three chamber ensembles), Pierrot Pierrot! (1980; flutes, celesta, percussion); Paradiso, Michele: Pierrot: Ballet for Piano (in Four Hands) and Orchestra (2008); Pirola, Carlo: Story of Pierrot (n.d.; brass band); Stuppner, Hubert: Pierrot and Pierrette (1984; ballet, libretto by Arthur Schnitzler [see The Veil of Pierrette under Plays, playlets, pantomimes, and revues]); Vidale, Piero: Pierrot's Dream: Four Fantasy Impressions (1957; orchestra).

- Russian—Koshkin, Nikita: "Pierrot and Harlequin", from Masquerades, II (1988; guitar); Voronov, Grigori: Pierrot and Harlequin (n.d. [recorded 2006]; saxophone and piano).

- Swiss—Gaudibert, Éric: Pierrot, to the table! or The Poet's Supper (2003; percussion, accordion, saxophone, horn, piano).

- Uruguayan—Pasquet, Luis (emigrated to Finland 1974): Triangle of Love (n.d.; #1: “Pierrot”; piano and brass band).

- Opera

- American (U.S.A.)—Baksa, Robert: Aria da Capo (1968); Bilotta, John George: Aria da Capo (1980); Blank, Allan: Aria da Capo (1958–60); Smith, Larry Alan: Aria da Capo (1980)—all libretti by Edna St. Vincent Millay (see above under Plays, playlets, pantomimes, and revues).

- French—Margoni, Alain: Pierrot, or The Secrets of the Night (1990; libretto by Rémi Laureillard adapted from Michel Tournier; see above under Fiction).

- See also Pierrot lunaire below.

Rock/pop

Group names and costumes

- American—Lady Gaga appears as Pierrot on the cover of her single "Applause" from her album Artpop (2013); Michael Jackson appears as Pierrot on the cover of the Michael Jackson Mega Box (2009), a DVD collection of interviews with the singer.

- British—David Bowie dressed as Pierrot for the video of Ashes to Ashes (1980) and for the sleeve of his album Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) (1980); Leo Sayer dressed as Pierrot on tour following the release of his first album, Silverbird (1973); Robots in Disguise: The Tears (2008), a video directed by Graeme Pearce, features black-suited Pierrots involved in love triangle.

- Hungarian—Pierrot's Dream was a rock band performing from 1985 to 1995; its singer-founder Tamás Z. Marosi often appeared in a clown half-mask.

- Italian—Pierrot Lunaire was a progressive rock/folk band.

- Japanese—Közi often wore a Pierrot costume while a member of the visual rock band Malice Mizer (1992–2001); Pierrot was a rock band active from 1994 to 2006.

- Russian—Cabaret Pierrot le Fou is a cabaret-noir group formed by Sergey Vasilyev in 2009; The Moon Pierrot was a conceptual rock band active from 1985 to 1992; it released its English-language studio album The Moon Pierrot L.P. in 1991 (a second album, Whispers and Shadows, recorded in 1992, was not released until 2013).

Songs, albums, and rock musicals

- American (U.S.A.)—Joe Dassin (worked mainly in France): "Pauvre Pierrot" ("Poor Pierrot"), from Elle était oh!... (1971); Thomas Nöla et son Orchestre: "Les Pierrots", in Soundtrack to the Doctor (2006).

- Australian—Katie Noonan and Elixir: "Pierrot", from First Seed Ripening (2011); The Seekers: "The Carnival Is Over" (1965: "But the joys of love are fleeting/For Pierrot and Columbine").

- Belgian—Sly-Dee: Histoire de Pierrot (Pierrot's Story [1994]).

- Brazilian—Los Hermanos: "Pierrot", from Los Hermanos (1999); Marina Lima: Pierrot de Brasil (1998).

- British—Ali Campbell: "Nothing Ever Changes (Pierrot)", from Flying High (2009); David Bowie: Pierrot in Turquoise (1993; includes following songs from the film of the same title: "Threepenny Pierrot", "Columbine", "The Mirror", "When I Live My Dream [1 & 2]"); Michael Moorcock and the Deep Fix: "Birthplace of Harlequin", "Columbine Confused", "Pierrot's Song of Positive Thinking", and "Pierrot in the Roof Garden", from The Entropy Tango and Gloriana Demo Sessions (2008); Petula Clark: "Pierrot pendu" ("Hanged Pierrot"), from Hello Mister Brown (1966); Placebo: "Pierrot the Clown", from Meds (2006); Rick Wakeman: "The Dancing Pierrot", from The Art in Music Trilogy (1999); Soft Machine: "Thank You Pierrot Lunaire", from Volume Two (1969).

- Czech—Václav Patejdl: Grand Pierrot (1995; rock musical).

- Dutch—Bonnie St. Claire: "Pierrot" (1980).

- French—Alain Kan: "Au pays de Pierrot" ("In Pierrot Country" [1973]); Chantal Goya: "Les pierrots de Paris" and "Pierrot tout blanc" ("Pure White Pierrot"), in Monsieur le Chat Botté (1982); Danielle Licari: "Les Chansons de Pierrot" (1981); Guy Béart: "Pierrot la tendresse" ("Pierrot the Tender"), from Béart à l'université de Louvain (1974); Gérard Lenorman: "Pierrot chanteur", from Le Soleil des Tropiques (1983); Jacques Dutronc: "Où est-il l'ami Pierrot?" ("Where's Friend Pierrot?"), from L'intégrale les Cactus (2004); Loïc Lantoine: "Pierrot", from Tout est calme (2006); Maxime Le Forestier: "Le Fantôme de Pierrot" ("Pierrot's Ghost"), from Hymne à sept temps (1976); Michèle Torr: “Dis Pierrot” (“Say Pierrot”), from film Une fille nommée amour (1969); Mireille Mathieu: "Mon copain Pierrot" ("My Friend Pierrot" [1967]); Pascal Danel: "Pierrot le sait" ("Pierrot Knows" [1966]); Pierre Perret: Le Monde de Pierrot (The World of Pierrot [2005]; double album); Renaud: "Chanson pour Pierrot", from Ma Gonzesse (1979).