Pierre Loti

| Pierre Loti | |

|---|---|

|

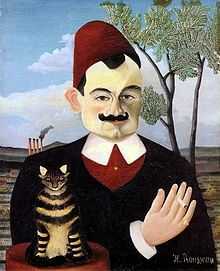

Loti on the day of his reception at the Académie française on 7 April 1892 | |

| Born |

14 January 1850 France |

| Died | 10 June 1923 |

| Occupation | French navy officer, writer |

| Nationality | French |

|

| |

| Signature |

|

Pierre Loti (pseudonym of Julien Viaud; 14 January 1850 – 10 June 1923) was a French novelist and naval officer. [1]

Biography

Loti's education began in his birthplace, Rochefort, Charente-Maritime. At the age of seventeen he entered the naval school in Brest and studied at Le Borda. He gradually rose in his profession, attaining the rank of captain in 1906. In January 1910 he went on the reserve list. He was in the habit of claiming that he never read books, saying to the Académie française on the day of his introduction (7 April 1892), "Loti ne sait pas lire" ("Loti doesn't know how to read"), but testimony from friends proves otherwise, as does his library, much of which is preserved in his house in Rochefort. In 1876 fellow naval officers persuaded him to turn into a novel passages in his diary dealing with some curious experiences at Istanbul. The result was the anonymously published Aziyadé (1879), part romance, part autobiography, like the work of his admirer, Marcel Proust, after him.

He proceeded to the South Seas as part of his naval training, and several years after leaving Tahiti published the Polynesian idyll originally named Rarahu (1880), which was reprinted as Le Mariage de Loti, the first book to introduce him to the wider public. His narrator explains that the name Loti was bestowed on him by the natives, after a red flower. The book inspired the 1883 opera Lakmé by Léo Delibes.

This was followed by Le Roman d'un spahi (1881), a record of the melancholy adventures of a soldier in Senegal. In 1882, Loti issued a collection of four shorter pieces, three stories and a travel piece, under the general title of Fleurs d'ennui (Flowers of Boredom).

In 1883 he entered a wider public spotlight. First, he published the critically acclaimed Mon frère Yves (My Brother Yves), a novel describing the life of a French naval officer (Pierre Loti), and a Breton sailor (Yves Kermadec), described by Edmund Gosse as "one of his most characteristic productions". Second, while serving in Tonkin (northern Vietnam) as a naval officer aboard the ironclad Atalante, Loti published three articles in the newspaper Le Figaro in September and October 1883 about atrocities that occurred during the Battle of Thuan An (20 August 1883), an attack by the French on the Vietnamese coastal defenses of Hue. He was threatened with suspension from the service for this indiscretion, thus gaining wider public notoriety. In 1884 his friend Émile Pouvillon dedicated his novel L'Innocent to Loti.

In 1886 he published a novel of life among the Breton fisherfolk, called Pêcheur d'Islande (An Iceland Fisherman), which Edmund Gosse characterized as "the most popular and finest of all his writings."[1] It shows Loti adapting some of the Impressionist techniques of contemporary painters, especially Monet, to prose, and is a classic of French literature. In 1887 he brought out a volume "of extraordinary merit, which has not received the attention it deserves", Propos d'exil, a series of short studies of exotic places, in his characteristic semi-autobiographic style. Madame Chrysanthème, a novel of Japanese manners that is a precursor to Madame Butterfly and Miss Saigon (a combination of narrative and travelog) was published the same year.[2]

In 1890 he published Au Maroc, the record of a journey to Fez in company with a French embassy, and Le Roman d'un enfant (The Story of a Child), a somewhat fictionalized recollection of Loti's childhood that would greatly influence Marcel Proust. A collection of "strangely confidential and sentimental reminiscences", called Le Livre de la pitié et de la mort, (The Book of Pity and Death) was published in 1891.

Loti was aboard ship at the port of Algiers when news reached him of his election, on 21 May 1891, to the Académie française. In 1892 he published Fantôme d'orient, a short novel derived from a subsequent trip to Istanbul, less a continuation of Aziyadé than a commentary on it. He described a visit to the Holy Land in three volumes, The Desert, Jerusalem, and Galilee, (1895–1896), and wrote a novel, Ramuntcho (1897), a story of contraband runners in the Basque province, which is one of his best writings. In 1898 he collected his later essays as Figures et Choses qui passaient (Passing Figures and Things).

In 1899 and 1900 Loti visited British India, with the view of describing what he saw; the result appeared in 1903 in L'Inde (India (without the English)). During the autumn of 1900 he went to China as part of the international expedition sent to combat the Boxer Rebellion. He described what he saw there after the siege of Beijing in Les Derniers Jours de Pékin (The Last Days of Peking, 1902).

Among his later publications were: La Troisième jeunesse de Mme Prune (The Third Youth of Mrs. Plum, 1905), which resulted from a return visit to Japan and once again hovers between narrative and travelog; Les Désenchantées (The Unawakened, 1906); La Mort de Philae (The Death of Philae, 1908), recounting a trip to Egypt; Judith Renaudin (produced at the Théâtre Antoine, 1898), a five-act historical play that Loti presented as based on an episode in his family history; and, in collaboration with Emile Vedel, a translation of King Lear, produced at the Théâtre Antoine in 1904. Les Désenchantées, which concerned women of the Turkish harem, was based like many of Loti's books, on fact. It has, however, become clear that Loti was in fact the victim of a cruel hoax by three prosperous Turkish women.[3]

In 1912 he mounted a production of The Daughter of Heaven, authored several years earlier in collaboration with Judith Gautier for Sarah Bernhardt, at the Century Theatre in New York City.

He died in 1923 at Hendaye and was interred on the Île d'Oléron with a state funeral.

Loti was an inveterate collector and his marriage into wealth helped him support this habit. His house in Rochefort, a remarkable reworking of two adjacent bourgeois row houses, is preserved as a museum.[4] One elaborately tiled room is an Orientalist fantasia of a mosque, including a small fountain and five ceremoniously draped coffins containing desiccated bodies. Another room evokes a medieval banqueting hall. Loti's own bedroom is rather like a monk's cell, but mixes Christian and Muslim religious artifacts. The courtyard described in The Story of a Child, with the fountain built for him by his older brother, is still there.

Works

Contemporary critic Edmund Gosse gave the following assessment of his work:[1]

At his best Pierre Loti was unquestionably the finest descriptive writer of the day. In the delicate exactitude with which he reproduced the impression given to his own alert nerves by unfamiliar forms, colors, sounds and perfumes, he was without a rival. But he was not satisfied with this exterior charm; he desired to blend with it a moral sensibility of the extremest refinement, at once sensual and ethereal. Many of his best books are long sobs of remorseful memory, so personal, so intimate, that an English reader is amazed to find such depth of feeling compatible with the power of minutely and publicly recording what is felt. In spite of the beauty and melody and fragrance of Loti's books his mannerisms are apt to pall upon the reader, and his later books of pure description were rather empty. His greatest successes were gained in the species of confession, half-way between fact and fiction, which he essayed in his earlier books. When all his limitations, however, have been rehearsed, Pierre Loti remains, in the mechanism of style and cadence, one of the most original and most perfect French writers of the second half of the 19th century.

Critical reception from the Turks

In response to Pierre Loti's support for the Turkish War of Independence, the Council of Ministers sent him a message of gratitude.[5] In spite of his orientalist views, he received a positive critical reception from Turkish intellectuals. According to the poet Nazım Hikmet, Loti's apparent criticism of Turkish society was actually an expression of his pity for the sorry state of the backward Ottoman Empire. In a 1925 poem named Şarlatan Piyer Loti (Charlatan Pierre Loti) Hikmet wrote:

Hatta sen

- sen Pier Loti!

- Sarı muşamba derilerimizden

- birbirimize

- geçen

- tifüsün biti

- senden daha yakındır bize

- Fransız zabiti!

Translation:

As for you

- you Pierre Loti!

- through our yellow tarpaulin hides

- among us

- the traveling

- typhous louse

- is closer to us than you are

- French officer!

In prose: "As for you, you Pierre Loti! The typhous louse that passes between us through our tarpaulin hides is closer to us than you are, French officer." Nonetheless, the Turkish government named one of Istanbul's famous hills "Pierre Loti Tepesi" or "Hill of Pierre Loti". Also, there is a coffee shop located at the top of that hill which changed its name to "Piere Loti Coffee Shop", and there is also a Pierre Loti Street in another part of Istanbul - all of which suggests that most Turkish people have not yet forgetten Pierre Loti.

Bibliography

| French literature |

|---|

| by category |

| French literary history |

| French writers |

|

| Portals |

|

- Aziyadé (1879)

- Le Mariage de Loti (originally titled Rarahu (1880)

- Le Roman d'un Spahi (1881)

- Fleurs d'Ennui (1882)

- Mon Frère Yves (1883) (English translation My Brother Yves)

- Les Trois Dames de la Kasbah (1884), which first appeared as part of Fleurs d'Ennui.

- Pêcheur d'Islande (1886) (English translation An Iceland Fisherman)

- Madame Chrysanthème (1887)[6]

- Propos d'Exil (1887)

- Japoneries d'Automne (1889)

- Au Maroc (1890)

- Le Roman d'un Enfant (1890)

- Le Livre de la Pitié et de la Mort (1891)

- Fantôme d'Orient (1892)

- L'Exilée (1893)

- Matelot (1893)

- Le Désert (1895)

- Jérusalem (1895)

- La Galilée (1895)

- Ramuntcho (1897)

- Figures et Choses qui passaient (1898)

- Judith Renaudin (1898)

- Reflets de la Sombre Route (1899)

- Les Derniers Jours de Pékin (1902)

- L'Inde sans les Anglais (1903)

- Vers Ispahan (1904)

- La Troisième Jeunesse de Madame Prune (1905)

- Les Désenchantées (1906)

- La Mort de Philae (1909)

- Le Château de la Belle au Bois dormant (1910)

- Un Pèlerin d'Angkor (1912)

- La Turquie Agonisante (1913) An English translation "Turkey in Agony" was published in the same year

- La Hyène Enragée (1916)

- Quelques Aspects du Vertige Mondial (1917)

- L'Horreur Allemande (1918)

- Prime Jeunesse (1919)

- La Mort de Notre Chère France en Orient (1920)

- Suprêmes Visions d'Orient (1921), written with the help of his son Samuel Viaud

- Un Jeune Officier Pauvre (1923, posthumous)

- Lettres à Juliette Adam (1924, posthumous)

- Journal Intime (1878–1885), 2 vol ("Private Diary", 1925–1929)

- Correspondence Inédite (1865–1904, unpublished correspondence, 1929)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 This article is derived largely from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition (1911) article "Pierre Loti" by Edmund Gosse. Unless otherwise referenced, it is the source used throughout, with citations made for specific quotes by Gosse.

- ↑ See also Madame Chrysanthème by Messager.

- ↑ Ömer Koç, 'The Cruel Hoaxing of Pierre Loti' Cornucopia, Issue 3, 1992, Cornucopia.net

- ↑ http://travel.michelin.com/web/destination/France-French_Atlantic_Coast-Rochefort/tourist_site-Pierre_Loti_s_House-r_Pierre_Loti

- ↑ Cultural Ministry of Turkey (Turkish)

- ↑ Pierre Loti (1908). Madame Chrysanthème. Current literature publishing company.

- Berrong, Richard M. (2013). Putting Monet and Rembrandt into Words: Pierre Loti's Recreation and Theorization of Claude Monet's Impressionism and Rembrandt's Landscapes in Literature. Chapel Hill: North Carolina Studies in Romance Language and Literature. vol 301.

- Editors, Robert Aldrich and Garry Wotherspoon (2002). Who's Who in Gay and Lesbian History from Antiquity to World War II. Routledge; London. ISBN 0-415-15983-0.

- Lesley Blanch (UK:1982, US:1983). Pierre Loti: Portrait of an Escapist. US: ISBN 978-0-15-171931-0 / UK: ISBN 978-0-00-211649-7 – paperback re-print as Pierre Loti: Travels with the Legendary Romantic (2004) ISBN 978-1-85043-429-0

- Edmund B. D'Auvergne (2002). Pierre Loti: The Romance of a Great Writer. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4325-7394-2 (paper), ISBN 978-0-7103-0864-1 (hardcover).

- Ömer Koç, 'The Cruel Hoaxing of Pierre Loti' Cornucopia, Issue 3, 1992

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Loti, Pierre". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Loti, Pierre". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pierre Loti. |

Official

- Official site of Maison Pierre Loti, house museum in Rochefort, in French.

Sources

- Works by Pierre Loti at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Pierre Loti at Internet Archive

- Works by or about Julien Viaud at Internet Archive

- Works by Pierre Loti at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

Commentary

- Rene Doumie. Contemporary French Novelists. New York, Boston : T. Y. Crowell & company. 1899. Biography and critical summary of Loti. From Internet Archive.

- Edmund Gosse. French Profiles. New York : Dodd, Mead and company. 1905. Collected reviews of Loti's works, by literary critic Edmund Gosse. From Internet Archive.

- Albert Leon Guerard. Five Masters of French Romance: Anatole France, Pierre Loti, Paul Bourget, Maurice Barrès, Romain Rolland. London T. Fisher Unwin. 1916. Biography and literary survey of major works. From Internet Archive.

- Frank Harris. Contemporary portraits. Second series. New York. 1919. Personal recollections of Loti. From Internet Archive.

- Henry James, ed. Impressions. Westminster : A. Constable and Co. 1898. Introduction by Henry James about Loti's life and works. From Internet Archive.

- Winifred (Stephens) Whale. French Novelists of To-day. London : John Lane; New York, John Lane company. 1908; see chapter "Pierre Loti", biography and literary survey. From Internet Archive.

- Easter Island Foundation sells an English translation of Loti's account of his visit to Easter Island, along with those of Eugène Eyraud, Hippolyte Roussel and Alphonse Pinart, under the title Early Visitors to Easter Island 1864–1877.

- Pierre Lotis' Madame Chrysanthème

| ||||||

|