Pickens County Courthouse (Alabama)

|

Pickens County Courthouse | |

| |

| Location | Carrollton, Alabama |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 33°15′42.37″N 88°5′42.31″W / 33.2617694°N 88.0950861°WCoordinates: 33°15′42.37″N 88°5′42.31″W / 33.2617694°N 88.0950861°W |

| Built | 1877 |

| Architectural style | Italianate |

| Governing body | Local |

| NRHP Reference # | 94000441 [1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | May 19, 1994 |

| Designated ARLH | July 23, 1976 |

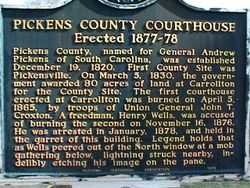

The Pickens County Courthouse in Carrollton, Alabama is the courthouse for Pickens County, Alabama. It is famous for a ghostly image that can be seen in one of its windows, claimed to be the face of Henry Wells, who allegedly was falsely accused of burning down the town's previous courthouse and was lynched in 1878.

Face in the courthouse window

What follows is the commonly told story of how the face appeared in the window. For the actual events see the section "Origins of the Story," below. On November 16, 1876, the people of Carrollton, Alabama watched helplessly as their courthouse burned to the ground. The Pickens County Courthouse had been a source of pride for the people of Carrollton. Their first courthouse had been burned down by invading Union Army troops during the American Civil War, an act that seemed to serve no purpose other than to inflict humiliation on the town. In the difficult days of the Reconstruction, when materials were scarce and money was even scarcer, rebuilding the courthouse seemed to be an impossible task. Yet, through hard work and deep personal sacrifices, the courthouse was somehow rebuilt. It stood as a testament to the perseverance of the town, and a symbol of defiance even in the face of defeat at the hands of the Union soldiers.

Yet, less than twelve years after Union troops had set fire to their first courthouse, the new one burned to a pile of smoldering ruin, apparently the result of a burglary gone wrong. Even as work began on a third courthouse, the townspeople demanded vengeance for the horrible act. Their vengeful eyes finally settled on Henry Wells, a freed slave who lived near the town.

Henry Wells was no angel. He was said to have a horrible temper, and there was no denying he had been involved in several brawls. Rumors went even further; people said he constantly carried a straight razor, and was not afraid to use it. Despite the rumors, however, there was only vague circumstantial evidence against him in the burning of the courthouse.

But it was Alabama in 1878, and Henry Wells was a black man accused of burning down a symbol of town pride. He was charged and arrested on four counts: arson, burglary, carrying a concealed weapon and assault with intent to murder. Ironically, he was taken to the sheriff's office, located inside the newly completed courthouse, to await trial.

As word spread through the town of Wells' arrest, the sheriff could sense trouble brewing. The mood of the town seemed as ominous as the dark clouds gathering in the late afternoon sky. As the first few drunken men began heading toward the courthouse, the sheriff took Wells to the high garret of the new courthouse, and told him to keep quiet. But as the angry mob gathered below, Wells' fear got the best of him. He went to the window, and looked down on the crowd. He yelled defiantly, at the top of his lungs, "I am innocent. If you kill me, I am going to haunt you for the rest of your lives!" Just then, a bolt of lightning struck nearby, flashing the image of Wells' face, contorted with fear, to the crowd below.

The lynch mob forced its way into the courthouse, and took their victim outside, even as he continued to proclaim his innocence. His cries went in vain, as the mob meted out its drunken vengeance, and dispersed. None of them even considered Wells' predictions of hauntings as they passed out in a drunken stupor. At least not until the next morning, that is.

Early the next morning, as a member of the lynch mob passed by the courthouse, he happened to glance up at the garret window. He was shocked to see Wells’ face looking down at him, just as it had the night before, when it had been illuminated by the flash of lightning. He rubbed his eyes and cursed his hangover, but when he looked back up, there was Wells. He screamed, and as others arrived, they all remembered Wells prediction. “If you kill me, I am going to haunt you for the rest of your lives!”

The face remains in the courthouse window to this very day. No amount of washing has been able to remove it, and on at least one occasion, it is said that every window pane in the courthouse was broken by a severe hailstorm; every pane, that is, except for the pane from which Wells continues to look down accusingly on the town that put him to death.

Another local version of this story is that while Wells was awaiting trial for being falsely accused of raping a white woman, a lightning storm brewed, and an angry mob gathered below to lynch him, and he told them, " If you lynch me, you will forever see my face." At this time lightning struck the very window in which he was standing. From that day forward, no amount of washing, or replacing that window, has been able to remove his face.

The image on the window

The image on the window is easily seen, although it is more face-like from some angles than from others. It is said that the image is only visible from outside the courthouse; from inside the pane appears to be a normal pane of glass.

Since the photo was taken, the city of Carrollton has installed a reflective highway sign with an arrow pointing to the pane where the image appears. There are permanent binoculars installed across the street from the window for those who wish to get a closer look.

In 2001, the courthouse was threatened with demolition, and the face was covered with a piece of plywood spray-painted with a smiley face. Due to a public campaign to save the face in the window, the courthouse is being renovated as funds become available.

Origins of the story

The story of the appearance of the face in the courthouse window seems to be a combination of two actual events, that of the lynching of Nathaniel Pierce, and that of the capture of Henry Wells, who later confessed to burning down the courthouse.

According to the West Alabamian, which was Carrollton's only newspaper at the time of the events, Nathaniel Pierce was being held for murder when, on September 26, 1877, an armed mob forced their way into the jail where Pierce was being held, took him outside the city, and killed him. There was no indication that Pierce’s lynching had anything to do with the burning of the courthouse.

In fact, the town already suspected Henry Wells and an accomplice, Bill Buckhalter, of the crime. A story in the West Alabamian on December 13, 1876 said that Henry Wells and Bill Buckhalter were suspected of robbing a store on the night the courtroom was burned. The story also reported that stolen merchandise from the store was found in their homes.

Wells’ accomplice, Buckhalter, was finally arrested in January 1878. Buckhalter confessed to the burglary, and blamed Wells for the burning of the courthouse. Wells was caught a few days later. When confronted by the police, he tried to flee, and was shot twice. He confessed to burning the courthouse, and died from his wounds five days later.

Although it is clear that these two events were combined into the commonly told story of how the face appeared in the courthouse window, neither of the two men could be the "face in the window." In fact, both Pierce and Wells died before the windows were ever installed in the new courthouse. The West Alabamian reported that windows were being installed in the courthouse on February 20, 1878. These windows were the windows in the main courtroom, which were the first windows installed due to a court session due to take place in the middle of March. The garret windows, including the one with the ghostly face, were not installed until weeks after Wells’ death.

Racial aspects of the story

The legend obviously contains scenes of the bitter racism that prevailed in Alabama during the Reconstruction Era, including lynching. In the legend, Henry Wells is depicted as an innocent man murdered by a vengeful, racist mob, while Wells was actually shot by law enforcement officers while fleeing arrest, and it is at least somewhat likely that Wells was in fact responsible for burning down the courthouse. In addition to the testimony of his accomplice, Wells eventually confessed to the crime, although his confession couldn't be seen as completely conclusive, given the circumstances under which it was given. Still, Wells' was arguably less "innocent" in the true events than he has come to be portrayed.

Given the racial history of Alabama, it is perhaps not surprising that a number of anecdotes told about the window have to do with race. John Harding Curry, who worked as a probate judge in the courthouse, recalls being concerned during the racial turmoil in Alabama during the late 1960s and early 1970s that someone might damage the window, as it could be seen to symbolize an era of terrible racism. However, despite the fact that the town did experience some instances of race-related vandalism, the window was never touched.

Curry also remembers, in the days before Alabama schools were integrated, a visit to the courthouse by children from a black school in Birmingham. Although Curry was initially reluctant, he decided to tell the students the entire story, ending his tale with a moral; "You might ask what that face in the courthouse is saying," he told the students. "It says to me, 'Don't ever let this happen again!'" He then asked the students if they had any questions. One little boy raised his hand and asked, "How do you know that's a black man up there?"

Spreading the story

Although the story was popular locally almost immediately, the story of the face in the courthouse window became widely known throughout the southeastern United States due to Kathryn Tucker Windham’s famous book of Alabama ghost stories, 13 Alabama Ghosts and Jeffrey. The story is also presented in Phantom Army of the Civil War and Other Southern Ghost Stories, edited by Frank Spaeth, and Ghost Stories from the American South, edited by W.K. McNeil.

In 2009 a play about the events surrounding Henry Wells and the burning of the second Courthouse was commissioned from playwright Barry Bradford by First National Bank of Central Alabama. Beginning in April 2010 the play - "The Face in the Courthouse Window" - [2] has been done each Spring in the courtroom of the Courthouse. All proceeds from the play go toward preservation of the Courthouse.[2]

See also

- Reportedly haunted locations in Alabama

References

- ↑ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 2007-01-23.

- ↑ http://www.courthousewindow.com

- Windham, Kathryn Tucker; Figh, Margaret Gillis. (1969). 13 Alabama Ghosts and Jeffrey. The University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-0376-6.

- "Skeptical Inquirer - The glaring garret ghost". Retrieved March 9, 2006.

- "Lightning Portrait of Henry Wells". Retrieved March 9, 2006.

- "Pickens County Courthouse". Alabama Ghostlore. Retrieved March 10, 2006.

| |||||||||||||||||