Phyllactinia guttata

| Phyllactinia guttata | |

|---|---|

| |

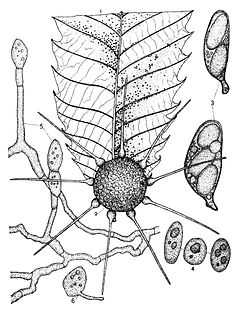

| Various stages in the life cycle of Phyllactinia guttata. Fig 1. Natural size, on chestnut leaf. 2. Perithecium enlarged. 3. Two asci. 4.Three sporidia. 5.Conidia-bearing hyphae. 6.Conidium germinating. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Phylum: | Ascomycota |

| Class: | Leotiomycetes |

| Subclass: | Leotiomycetidae |

| Order: | Erysiphales |

| Family: | Erysiphaceae |

| Genus: | Phyllactinia |

| Species: | P. guttata |

| Binomial name | |

| Phyllactinia guttata (Wallr.) Lév. | |

Phyllactinia guttata is a species of fungus in the Erysiphaceae family; the anamorph of this species is Ovulariopsis moricola. A plant pathogen distributed in temperate regions, P. guttata causes a powdery mildew on leaves and stems on a broad range of host plants; many records of infection are from Corylus species, like filbert (Corylus maxima) and hazel (Corylus avellana). Once thought to be conspecific with Phyllactinia chorisiae, a 1997 study proved that they are in fact separate species.[1]

Microscopically, P. guttata is characterized by large ascomata, long narrow pointed appendages with bulbous swellings at base, 2- or 3-spored asci with large ascospores; the ascomata also have gelatinous cells with tufts of hyphae somewhat resembling hairs.[2] The cleistothecia are capable of dissemination and attachment to new growing surfaces by means of gelatinous penicillate cells.

Taxonomy

Originally named in 1801 as Sclerotium erysiphe by Christian Hendrik Persoon, the species went through a number of name changes in the 1800s. Salmon's widely used 1900 monograph on the Erysiphaceae[3] established the name as Phyllactinia corylea for roughly half a century, until the starting date for the naming of fungi was moved, and the name was established as Phyllactinia guttata.[4]

Description

The mycelium may be abundant and persistent, or scant and short-lived (evanescent).[5] The cleistothecia can become large (216–245 µm), with soft wall tissue, and obscure cellular structure and cracks and wrinkles (reticulations).

The cleistothecia typically develop 8–12 easily detachable hyaline appendages that vary in length from 191–290 µm long. The asci are 4 to 5 to 20 or more, ovate, supported by small stalk-like structures (pedicellate), with dimensions of 72–83 by 32–40 µm. There are typically 2 spores per ascus, sometimes 3 or 4, and they are 31–36 by 21–25 µm.[6]

The cells attached to the upper part of the ascomata that resemble hairs are known as penicillate cells; they are made of foots and filaments. The filaments can gelatinize by absorbing water and are thought to function in helping the ascomata adhere to the surface on which they grow, like the underside of leaves.[7] In P. guttata, the foots are cylindrical, irregular in width, 32–72 by 7.5–25 µm, and divided into 2–10 branchlets in the upper part. Each branchlet is short, bulbous, with filaments being 20–42 µm, somewhat shorter than the foots, which are 2–4 µm wide. The short, bulbous branchlets on the multi-branched upper part of the foots are unique among the Phyllactinia and are a distinguishing taxonomic characteristic of this species.[2]

Habitat and distribution

P. guttula is distributed throughout temperate regions of the world, such as China, India, Iran, Japan, Korea, Turkey, the former USSR, Europe (widely distributed), Canada, and USA. This species can infect a wide variety of hosts in many plant families.[8] Examples include species from the Betulaceae family (Betula, Carpinus, Corylus, Ostrya), the Fagaceae (Castanea, Fagus, Quercus) and the Juglandaceae (Juglans, Platycarya, Pterocarya). It is also found on the genera Acer, Aesculus, Aralia, Asclepias, Azalea, Buxus, Catalpa, Chionanthus, Cornus, Frangula, Hedera, Humulus, Paliurus, Populus, Prunus, Rhamnus, Ribes, Salix, Sorbus, Syringa, and Ulmus.[9] P. guttata is a host for the fungicolous hyphomycete Cladosporium uredinicola.[10]

References

- ↑ Liberato JR. (1997). "Taxonomic notes on two powdery mildews: Phyllactinia chorisiae and Ovulariopsis wissadulae (Erysiphaceae : Phyllactinieae)". Mycotaxon 101: 29–34.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Shin H-D, Lee H-J. (2002). "Morphology of penicillate cells in the genus Phyllactinia and its taxonomic application". Mycotaxon 83: 301–325.

- ↑ Salmon ES. (1907). "A monograph on the Erysiphaceae". Memoirs of the Torrey Botanical Club 9: 1–292.

- ↑ Cooke WB. (1952). "Nomenclatural notes on the Erysiphaceae". Mycologia 44 (4): 570–74.

- ↑ Ellis JB, Everhart JM. (1892). North American Pyrenomycetes. New Jersey: Newfield. pp. 20–21.

- ↑ Eslyn WE. (1960). "New Records of Forest Fungi in the Southwest". Mycologia (Mycologia, Vol. 52, No. 3) 52 (3): 381–387. doi:10.2307/3755953. JSTOR 3755953.

- ↑ Yarwood CE. (1958). "Powdery mildews". Botanical Review 23: 235–301. doi:10.1007/bf02872581.

- ↑ "SMML Database results". Retrieved 2009-05-01.

- ↑ Kapoor JN. (1967). "Phyllactinia guttana". IMI Descriptions of Fungi and Bacteria 16: 157.

- ↑ Dugan F. (2006). "Phyllactinia guttata is a host for Cladosporium uredinicola in Washington state". North American Fungi: 1. doi:10.2509/pnwf.2006.001.001.

External links

- Index Fungorum Synonyms