Phonological history of English high back vowels

Most dialects of modern English have two high back vowels: the close back rounded vowel /u/ found in words like goose, and the near-close near-back rounded vowel /ʊ/ found in words like foot. This article discusses the history of these vowels in various dialects of English, focusing in particular on phonemic splits and mergers involving these sounds.

Foot–goose merger

The foot–goose merger is a phenomenon that occurs in Scottish English, Ulster varieties of Hiberno-English, Malaysian English and Singaporean English,[1] where the vowels /ʊ/ and /uː/ are merged. As a result, pairs like look/Luke are homophones and good/food and foot/boot rhyme. The quality of the merged vowel is usually [ʉ] or [y] in Scottish English and [u] in Singaporean English.[2] The use of the same vowel in "foot" and "goose" in these dialects is not due to phonemic merger, but the appliance of different languages' vowel system to the English lexical incidence.[3] The full–fool merger is a conditioned merger of the same two vowels before /l/, making pairs like pull/pool and full/fool homophones.

Foot–strut split

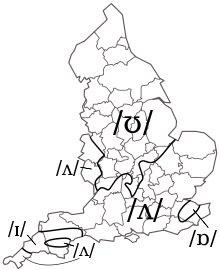

The foot–strut split is the split of Middle English short /u/ into two distinct phonemes /ʊ/ (as in foot) and /ʌ/ (as in strut) that occurs in most varieties of English; the most notable exceptions being those of Northern England and the English Midlands.[4]

The origin of the split is the unrounding of /ʊ/ in Early Modern English, resulting in the phoneme /ʌ/. In general (though with some exceptions), unrounding to /ʌ/ did not occur if /ʊ/ was preceded by a labial consonant (e.g., /p/, /f/, /b/) and followed by /l/, /ʃ/, or /tʃ/, leaving the modern /ʊ/. Because of the inconsistency of the split, the words put and putt became a minimal pair, distinguished as /pʊt/ and /pʌt/. The first clear description of the split dates from 1644.[5]

In non-splitting accents, cut and put rhyme, putt and put are homophonous as /pʊt/, and pudding and budding rhyme. However luck and look are not necessarily homophones; many accents in the area concerned have look as /luːk/, with the vowel of goose.

The absence of this split is a less common feature of educated Northern English speech than the absence of the trap–bath split.[6] The absence of the foot–strut split is sometimes stigmatized, and speakers of non-splitting accents often try to introduce it into their speech, sometimes resulting in hypercorrections such as pronouncing pudding /pʌdɪŋ/.

The name "foot–strut split" refers to the lexical sets introduced by Wells (1982), and identifies the vowel phonemes in the words. From a historical point of view, this name is inappropriate because foot and strut did not rhyme in Middle English (foot had Middle English /oː/ as its spelling suggests).

| mood goose tooth |

good foot book |

blood flood brother |

cut dull fun |

put full sugar | ||

| Middle English | oː | oː | oː | u | u | |

| Great Vowel Shift | uː | uː | uː | u | u | |

| Early Shortening | uː | uː | u | u | u | |

| Quality Adjustment | uː | uː | ʊ | ʊ | ʊ | |

| Foot–Strut Split | uː | uː | ɤ | ɤ | ʊ | |

| Later Shortening | uː | ʊ | ɤ | ɤ | ʊ | |

| Quality Adjustment | uː | ʊ | ʌ | ʌ | ʊ | |

| RP Output | uː | ʊ | ʌ | ʌ | ʊ | |

In modern standard varieties of English, e.g. RP and General American, the spelling is a reasonably good guide to whether a word is in the FOOT or STRUT lexical sets. The spellings o and u nearly always indicate the STRUT set (common exceptions are wolf, woman, pull, bull, full, push, bush, cushion, puss, put, pudding and butcher), while the spellings oo and ould usually indicate the FOOT set (common exceptions are blood and flood). The spellings of some words changed in accordance with this pattern: e.g. wull became wool and wud became wood. In some recent loan words such as Muslim both pronunciations are found.

Bruise–brews split

The bruise–brews split is the split of English /uː/ into two distinct phonemes:

- /uː/, which occurs in morphologically closed syllables (as in bruise /bruːz/);[7]

- /ɵʊ/, which occurs in morphologically open syllables (as in brews /brɵʊz/).[7]

Merger of Middle English /y/, /ɛu/, /eu/, and /iu/

Middle English distinguished the close front rounded vowel /y/ (occurring in loanwords from Anglo-Norman like duke) and the diphthongs /iu/ (occurring in words like new), /eu/ (occurring in words like few)[8] and /ɛu/ (occurring in words like dew).

By Early Modern English, /y/, /eu/, and /iu/ merged as /ɪu/ (with /ɛu/ merging with them a couple of centuries later), which has remained as such in some Welsh, northern English, and American accents in which through /θɹuː/ is distinct from threw /θɹɪu/.[9] In the majority of accents, however, /ɪu/ later became /juː/, which, depending on the preceding consonant, either remained or developed into /uː/ by the process of yod-dropping, hence the present pronunciations /d(j)uːk/, /n(j)uː/, and /fjuː/.

Shortening of /uː/ to /ʊ/

In a handful words, including some very common ones, the vowel /uː/ was shortened to /ʊ/. In a few of these words, notably blood and flood, this shortening happened early enough that the resulting /ʊ/ underwent the "foot–strut split" and are now pronounced with /ʌ/. Other words that underwent shortening later consistently have /ʊ/, such as good, book, and wool. Still other words, such as roof, hoof, and root are in the process of the shift today, with some speakers preferring /uː/ and others preferring /ʊ/ in such words. For some speakers in Northern England, words ending in -ook such as book, cook still have the long /uː/ vowel.

Change of /uː.ɪ/ to [ʊɪ]

The change of /uː.ɪ/ to [ʊɪ] is a process that occurs in many varieties of British English where bisyllabic /uː.ɪ/ becomes the diphthong [ʊɪ] in certain words. As a result, "ruin" is pronounced as monosyllabic [ˈɹʊɪn] and "fluid" is pronounced [ˈflʊɪd].

See also

- Phonological history of the English language

- Phonological history of English vowels

- Phonological history of English consonants

- English consonant-cluster reductions

- Yod-dropping

References

- ↑ HKE_unit3.pdf

- ↑ Wells, John C. (1982). Accents of English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 400–2, 438–39. ISBN 0-521-22919-7. (vol. 1). ISBN 0-521-24224-X (vol. 2)., ISBN 0-521-24225-8 (vol. 3).

- ↑ Macafee 2004: 74

- ↑ Wells, ibid., pp. 132, 196–99; 351–53

- ↑ Lass, Roger (2000). "Phonology and Morphology". In Lass, Roger. The Cambridge History of the English Language iii: 1476-1776. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 88–90. ISBN 0-521-26476-6.

- ↑ Wells, ibid., p. 354

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Watt & Allen (2003:269)

- ↑ http://www.courses.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/pronunciation/, http://facweb.furman.edu/~wrogers/phonemes/phone/me/mvowel.htm

- ↑ Wales, ibid., p. 206

Bibliography

- Watt, Dominic; Allen, William (2003), "Tyneside English", Journal of the International Phonetic Association 33 (2): 267–271, doi:10.1017/S0025100303001397

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||