Philippe-Jean Bunau-Varilla

| Philippe-Jean Bunau-Varilla | |

|---|---|

|

Philippe-Jean Bunau-Varilla was influential in the construction of the Panama Canal | |

| Born |

July 26, 1859 Paris |

| Died | 1940 |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Panama Canal |

Philippe-Jean Bunau-Varilla (French pronunciation: [filip ʒɑ̃ byno vaʁija]) (1859–1940), commonly referred to as simply Philippe Bunau-Varilla and Monsignor Brun Varilla, was a French engineer and soldier. With the assistance of American lobbyist and lawyer William Nelson Cromwell, Bunau-Varilla greatly influenced the United States' decision concerning the construction site for the famed Panama Canal. He also worked closely with United States president Theodore Roosevelt in the latter's orchestration of the Panamanian Revolution.

Early life

Bunau-Varilla was born on July 26, 1859 in Paris, France. After graduating at age 20 from the École Polytechnique, he remained in France for three years. In 1882 he abandoned his career in public works at the École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées and traveled to Panama. He arrived at the isthmus in 1884, employed with Ferdinand de Lesseps's Panama Canal Company. He became general manager of the organization and food.

Panama Canal

After the Panama Canal Company went bankrupt in 1888 amidst charges of fraud, Bunau-Varilla was left stranded in Panama. He struggled to find a new way to construct the canal. When the New Panama Canal Company sprang up back in his native France, Bunau-Varilla sailed home, having purchased a large amount of stock. However, as de Lesseps' company had before, the New Panama Canal Company soon abandoned efforts to build the canal. It sold the land in Panama to the United States, in hopes that the company would not fail entirely. U.S. President Grover Cleveland, an anti-imperialist, avoided the canal issue. With the election of the more supportive President Theodore Roosevelt, canal planning resumed in the United States.

Bunau-Varilla vociferously promoted construction of the canal. With aid from the New Panama Canal Company's New York attorney, William Nelson Cromwell, he persuaded the government to select Panama as the canal site, as opposed to the popular alternative, Nicaragua. When opponents voiced their interest in constructing a canal through Nicaragua, which was a less politically volatile nation, Bunau-Varilla actively campaigned throughout the Northeast, carrying pictures and postage stamps of Nicaragua's Mt. Momotombo spewing ash and lava over the proposed route. Through lobbying of businessmen, government officials, and the American public, Bunau-Varilla convinced the U.S. Senate to appropriate $40 million to the New Panama Canal Company, under the Spooner Act of 1902. The funds were contingent on negotiating a treaty with Colombia to provide land for the canal in its territory of Panama.

Separation of Panama from Colombia

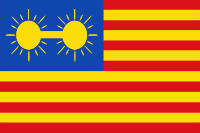

Colombia signed the Hay–Herrán Treaty in 1903, ceding land in Panama to the United States for the canal, but the Senate of Colombia rejected ratification. Bunau-Varilla's company was in danger of losing the $40 million of the Spooner Act, and he drew up plans with Panamanian juntas in New York for war. By the eve of the war, Bunau-Varilla had already drafted the new nation's constitution, flag, and military establishment, and promised to float the entire government on his own checkbook. Bunau-Varilla's flag design was later rejected by the Panamanian revolutionary council on the grounds that it was designed by a foreigner. Although he prepared for a small-scale civil war, violence was limited. As promised, President Roosevelt interposed a U.S. naval fleet between the Colombian forces south of the isthmus and Panamanian separatists.

U.S. control of the canal area

Bunau-Varilla, as Panama's ambassador to the United States, was invested with plenipotentiary powers by President Manuel Amador. Lacking formal consent of the government of Panama, he entered into negotiations with the American Secretary of State, John Hay, to give control of the Panama Canal area to the U.S. No Panamanians signed the resulting Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty, though it was ratified in Panama on December 2, 1903.[1] Bunau-Varilla had received his ambassadorship through financial assistance to the rebels, he had not lived in Panama for seventeen years, and he never returned,[2] leading to the charge that he was "appointed Minister by cable".[3] Panamanians long resented his betrayed trust put in him by the new Panamanian authorities. The treaty was finally undone by the Torrijos–Carter Treaties in 1977.

Career after the Panama Canal

In World War I, Bunau-Varilla served as an officer in the French army and lost a leg at the Battle of Verdun. As an elder lobbyist, he promoted altering the canal from a lock system to a sea-level waterway. He died in Paris, France on May 18, 1940.

Personal income

One of the more interesting aspects of Bunau-Varilla's life was his source of income. Guests to his elegant Paris residence often reflected on the immaculate grandeur of the home. He was known to entertain friends and strategic partners at some of the most pricey locations of his time. It was discovered where he got the money for such a grandiose existence. His money was not made as an engineer during his first stay working on the first Panama Canal project (under de Lesseps), nor did he inherit significant wealth from relatives or parents, having been born illegitimate. He made his fortune during his second stay in Panama from 1886 to 1889, where he ran his own company, ARTIGUE & SONDEREGGER, together with his brother Maurice, who later became the rich owner of Le Matin, a major Parisian newspaper.[4]

See also

References

- ↑ 47.html

- ↑ "The 1903 Treaty and Qualified Independence". U.S. Library of Congress. 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-01.

- ↑ Francisco Escobar (Jul 13, 1914). "Why the Colombian Treaty Should be Ratified". The Independent. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- ↑ The Bunau-Varilla Brothers and the Panama canal by Gabriel J Loizillon

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Philippe Bunau-Varilla. |

- Historical Text Archive

- "The Man Who Invented Panama", by Eric Sevareid

- "Philippe Jean Bunau-Varilla Biography" at Book Rags

- Encyclopædia Britannica

- Kennedy, David M., Lizabeth Cohen, and Thomas A. Bailey. American Pageant. 12th ed. U.S.: Houghton Mifflin, 2001.

- McCullough, David. The Path Between the Seas

- Mellander, Gustavo A.(1971) The United States in Panamanian Politics: The Intriguing Formative Years. Daville,Ill.:Interstate Publishers. OCLC 138568.

- Mellander, Gustavo A.; Nelly Maldonado Mellander (1999). Charles Edward Magoon: The Panama Years. Río Piedras, Puerto Rico: Editorial Plaza Mayor. ISBN 1-56328-155-4. OCLC 42970390.

- Works by Edward B. Fishman, Bunau-Varilla historian

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|