Philip II of France

| Philip II | |

|---|---|

Seal of Philip II | |

| King of France | |

| Junior king Senior king |

1 November 1179 – 18 September 1180 18 September 1180 – 14 July 1223 |

| Coronation | 1 November 1179 |

| Predecessor | Louis VII |

| Successor | Louis VIII |

| Spouse |

Isabella of Hainaut Ingeborg of Denmark Agnes of Merania |

| Issue |

Louis VIII, King of France Marie, Duchess of Brabant Philip I, Count of Boulogne |

| House | House of Capet |

| Father | Louis VII, King of France |

| Mother | Adèle of Champagne |

| Born |

21 August 1165 Gonesse, France |

| Died |

14 July 1223 (aged 57) Mantes-la-Jolie, France |

| Burial | Saint Denis Basilica |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

Philip II, called Philip Augustus (French: Philippe Auguste; 21 August 1165 – 14 July 1223) was a Capetian King of France who reigned from 1180 to 1223, and the first to be called by that title. His predecessors had been known as kings of the Franks but from 1190 onward Philip styled himself king of France. The son of Louis VII and of his third wife, Adela of Champagne, he was originally nicknamed "God-given" because he was the first son of Louis VII and born late in his father's life.[1]

After a twelve year struggle with the Plantagenet dynasty, Philip broke up the large Angevin Empire and defeated a coalition of his rivals (German, Flemish and English) at the Battle of Bouvines in 1214. This victory would have a lasting impact on western European politics: the authority of the French king became unchallenged, while the English king was forced by his barons to sign the Magna Carta and faced a rebellion in which Philip intervened, the First Barons' War.

Philip did not directly participate in the Albigensian Crusade, but he allowed his vassals and knights to carry it out, preparing the subsequent expansion of France southward.

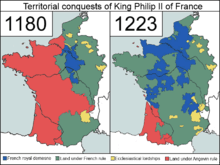

Philip was nicknamed "Augustus" by the chronicler Rigord for having remarkably extended the royal demesne, the domains ruled directly by the kings of France, as opposed to the territories ruled indirectly by vassals of the king.

He checked the power of the nobles and helped the towns to free themselves from seigniorial authority, granting privileges and liberties to the emergent Bourgeoisie. He built a great wall around Paris, reorganized the government and brought financial stability to the country.

Philip Augustus transformed France from a small feudal state into the most prosperous and powerful country in Europe. He died in 1223 and was succeeded by his son, Louis VIII. Knowing his own declining health would inevitably decrease his political strength, he was the first Capetian king not to have his eldest son anointed to act as co-ruler during his lifetime; instead his son acted as sole king.

Early years

Philip was born in Gonesse on 21 August 1165.[2] As soon as he was able, Louis planned to associate Philip with him on the throne, but it was delayed when Philip, at the age of thirteen, was separated from his companions during a royal hunt and became lost in the Forest of Compiègne. He spent much of the following night attempting to find his way out, but to no avail. Exhausted by cold, hunger and fatigue, he was eventually discovered by a peasant carrying a charcoal burner, but his exposure to the elements meant he soon contracted a dangerously high fever.[3] His father went on pilgrimage to the Shrine of Thomas Becket to pray for Philip's recovery and was told that his son had indeed recovered. However, on his way back to Paris, he suffered a stroke.

In declining health, Louis VII had his 14 year old son crowned and anointed at Rheims by the Archbishop William Whitehands on 1 November in 1179. He was married on 28 April 1180 to Isabelle of Hainaut, who brought the County of Artois as her dowry. From his coronation, all real power was transferred to Philip, as his father slowly descended into senility.[3] The great nobles were discontented with Philip's advantageous marriage, while his mother and four uncles, all of whom exercised enormous influence over Louis, were extremely unhappy with his association to the throne, causing a diminution in their power.[4] Eventually, Louis died on 18 September 1180.

Consolidation of royal demesne

While the royal demesne had increased under Philip I and Louis VI, under Louis VII it had diminished slightly. In April 1182, Philip expelled all Jews from the demesne and confiscated their goods. Philip's eldest son, Louis, was born on 5 September in 1187 and inherited Artois in 1190, when his mother Isabelle died. The main source for Philip's army was from the royal demesne. In times of conflict, he could immediately call up 250 knights, 250 horse sergeants, 100 crossbowmen (mounted), 133 crossbowmen (foot), 2,000 foot sergeants, and 300 mercenaries.[5] Towards the end of his reign, the King could muster some 3,000 knights, 9,000 sergeants, 6,000 urban militiamen, and thousands of foot sergeants.[6] Using his increased revenues, Philip was the first Capetian king to actively build a French navy. By 1215, his fleet could carry a total of 7,000 men. Within two years his fleet included 10 large ships and many smaller ones.[7]

Wars with his vassals

In 1181, Philip began a war with Philip, Count of Flanders, over the Vermandois, which King Philip claimed as his wife's dowry and the Count was unwilling to give up. Finally the Count of Flanders invaded France, ravaging the whole district between the Somme and the Oise before penetrating as far as Dammartin.[8] Notified of Philip's impending approach with 2,000 knights, he turned around and headed back to Flanders.[9] Philip chased him, and the two armies confronted each other near Amiens. By this stage, Philip had managed to counter the ambitions of the count by breaking his alliances with Henry I, Duke of Brabant, and Philip of Heinsberg, Archbishop of Cologne. This, together with an uncertain outcome were he to engage the French in battle, forced the Count to conclude a peace.[8] In July 1185, the Treaty of Boves left the disputed territory partitioned, with Amiénois, Artois, and numerous other places passing to the King, and the remainder, with the county of Vermandois proper, left provisionally to Philip of Alsace.[10] It was during this time that Philip II was nicknamed "Augustus" by the monk Rigord for augmenting French lands.[11]

Meanwhile in 1184, Stephen I of Sancerre and his Brabançon mercenaries ravaged the Orléanais. Philip defeated him with the aid of the Confrères de la Paix.

War with Henry II

Philip also began to wage war with Henry II of England, who was also Count of Anjou and Duke of Normandy and Aquitaine in France. The death of Henry's eldest son, Henry the Young King, in June 1183 began a dispute over the dower of Philip's widowed sister Margaret. Philip insisted that the dower should be returned to France as the marriage did not produce any children, as per the betrothal agreement.[12] The two kings would hold conferences at the foot of an elm tree near Gisors, which was so positioned that it would overshadow each monarch's territory, but to no avail. Philip pushed the case further when King Béla III of Hungary asked for the widow's hand in marriage, and thus her dowry had to be returned, to which Henry finally agreed.

The death of Henry's fourth son, Geoffrey II, Duke of Brittany, in 1186 began a new round of disputes, as Henry insisted that he retain the guardianship of the duchy for his unborn grandson Arthur I, Duke of Brittany.[12] Philip, as Henry's liege lord, objected, stating that he should be the rightful guardian until the birth of the child. Philip then raised the issue of his other sister, Alys, Countess of the Vexin, and her delayed betrothal to Richard the Lionheart.

With these grievances, two years of combat (1186–1188) followed, but the situation remained unchanged. Philip initially allied with Henry's young sons, Richard the Lionheart and John Lackland, who were in rebellion against their father. Philip II launched an attack on Berry in the summer of 1187 but then in June made a truce with Henry, which left Issoudun in his hands and also granted him Fréteval, in Vendômois.[10] Though the truce was for two years, Philip found grounds for resuming hostilities in the summer of 1188. He skilfully exploited the estrangement between Henry and Richard, and Richard did homage to him voluntarily at Bonsmoulins in November 1188.[10]

Then in 1189 Richard openly joined forces with Philip to drive Henry into abject submission. They chased him from Le Mans to Saumur, losing Tours in the process,[12] before forcing him to acknowledge Richard as his heir. Finally, by the Treaty of Azay-le-Rideau (4 July 1189), Henry was forced to renew his own homage, to confirm the cession of Issoudun, with Graçay also, to Philip, and to renounce his claim to suzerainty over Auvergne.[10] Henry died two days later. His death, and the news of the fall of Jerusalem to Saladin, diverted attention from the Franco-English war.

Philip befriended all of Henry's sons and used them to foment rebellion against their father, but he turned against both Richard and John after their respective accessions to the throne. The Angevin Kings of England, as Dukes of Normandy and Aquitaine, and Count of Anjou, were his most powerful and dangerous vassals. Philip made it his life's work to destroy Angevin power in France. He maintained friendships with Henry the Young King and Geoffrey II until their deaths. Indeed, at the funeral of Geoffrey, he was so overcome with grief that he had to be forcibly restrained from casting himself into the grave.

Third Crusade

Philip went on the Third Crusade (1189–1192) with King Richard I of England (The Lionheart) and the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick I Barbarossa. His army left Vézelay on 1 July 1190. At first the French and English crusaders travelled together, but the armies split at Lyon, as Richard decided to go by sea, and Philip took the overland route through the Alps to Genoa. The French and English armies were reunited in Messina, where they wintered together. On 30 March 1191 the French set sail for the Holy Land and Philip arrived on 20 May. He then marched to Acre, which was already under siege by a lesser contingent of crusaders, and he started to construct siege equipment before Richard arrived in 8 June. By the time Acre surrendered on 12 July, Philip was severely ill with dysentery, which reduced his zeal. Ties with Richard were further strained after the latter acted in a haughty manner after Acre had fallen.

More importantly, the siege resulted in the death of Philip of Alsace, who held the county of Vermandois proper, threatening to derail the Treaty of Gisors that Philip had orchestrated to isolate the powerful Blois-Champagne faction. Philip decided to return to France to settle the issue of succession in Flanders, a decision that displeased Richard, who said, "It is a shame and a disgrace on my lord if he goes away without having finished the business that brought him hither. But still, if he finds himself in bad health, or is afraid lest he should die here, his will be done." So on 31 July 1191 the French army of 10,000 men (along with 5,000 silver marks to pay the soldiers) remained in Outremer under the command of Hugh III, Duke of Burgundy. Philip and his cousin Peter of Courtenay, count of Nevers, made their way to Genoa and from there returned to France. The decision to return was also fuelled by the realisation that with Richard campaigning in the Holy Land, English possessions in northern France (Normandy) would be open for attack. After Richard's delayed return home, war between England and France would ensue over possession of English-controlled territories in modern-day France.

Conflict with England, Flanders and the Holy Roman Empire

Conflict with King Richard the Lionheart 1192–1199

The immediate cause of the conflict with Richard the Lionheart stemmed from Richard's decision to break his betrothal with Phillip's sister Alys at Messina in 1191.[13] Part of Alys's dowry that had been given over to Richard during their engagement was the territory of the Vexin, which included the strategic fortress of Gisors. This should have reverted to Philip upon the end of the betrothal, but Philip, to prevent the collapse of the Crusade, agreed that this territory was to remain in Richard's hands and would be inherited by his male descendents. Should Richard die without an heir, the territory would return to Philip, and if Philip died without an heir, those lands would be considered a part of Normandy.[13]

Returning to France in late 1191, Phillip began plotting to find a way to have those territories restored to him. He was in a difficult situation, as he had taken an oath not to attack Richard 's lands while he was away,[14] and as Richard was still on Crusade, his territory was under the protection of the Church in any event. Philip had unsuccessfully asked Pope Celestine III to release him from his oath,[15] and as a result he was forced to build a casus belli from scratch.

On 20 January 1192, Philip met with William FitzRalph, Richard's seneschal of Normandy. Presenting some documents purporting to be from Richard, Philip claimed that Richard had agreed at Messina to hand back the disputed lands to Philip. Not having heard anything directly from their sovereign, FitzRalph and the Norman barons rejected Philip's claim to the Vexin.[13] Philip at this time also began spreading rumours about Richard's action in the east to discredit the English king in the eyes of his subjects. Among the stories Philip invented included Richard involved in treacherous communication with Saladin, that he had conspired to cause the fall of Gaza, Jaffa, and Ashkelon, and that he had participated in the murder of Conrad of Montferrat.[15] Finally, Philip made contact with Prince John, Richard's brother, whom he convinced to join him and overthrow his brother.[15]

At the start of 1193, John visited Philip in Paris where he paid homage for Richard's continental lands. When word reached Philip that Richard had finished crusading and had been captured on his way back from the Holy Land, he promptly invaded the Vexin. His first target was the fortress of Gisors, commanded by Gilbert de Vascoeuil, which surrendered without putting up a struggle.[16] Philip then penetrated deep into Normandy, reaching as far as Dieppe. To keep the duplicitous John on his side, Philip entrusted the defence of the town of Évreux to him.[17] Meanwhile, Philip was joined by Count Baldwin of Flanders, and together they laid siege to the ducal capital of Normandy, Rouen. Here, Philip's advance was halted by a defence led by Earl Robert of Leicester.[16] Unable to penetrate their defences, Philip moved on.

At Mantes on 9 July 1193, Philip came to terms with Richard's ministers who agreed that Philip could keep his gains and would be given some extra territories if he ceased all further aggressive actions in Normandy, along with the condition that Philip would hand back the captured territory if Richard would pay homage to Philip.[16] To prevent Richard from spoiling their plans, Philip and John attempted to bribe the Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI to keep the English king captive for a little while longer. He refused, and Richard was released from captivity on 4 February 1194. By 13 March Richard had returned to England, and by 12 May he had set sail for Normandy with some 300 ships, eager to take the war to Philip.[16]

Philip had spent this time consolidating his territorial gains and by now controlled much of Normandy east of the Seine, while remaining within striking distance of Rouen. His next objective was the castle of Verneuil,[18] which had withstood an earlier siege. Once Richard arrived at Barfleur, he soon marched towards Verneuil. As his forces neared the castle, Philip, who had been unable to break through, decided to strike camp. Leaving a large force behind to prosecute the siege, he moved off towards Évreux, which Prince John had handed over to his brother to prove his loyalty.[18] Philip retook the town and sacked it, but during this time, his forces at Verneuil abandoned the siege, and Richard entered the castle unopposed on 30 May. Throughout June while Philip's campaign ground to a halt in the north, Richard was taking a number of important fortresses to the south. Philip, eager to relieve the pressure off his allies in the south, marched to confront Richard's forces at Vendôme. Refusing to risk everything in a major battle, Philip retreated, only to have his rear guard caught at Fréteval on 3 July, which turned into a general encounter that Philip only managed to avoid capture as his army was put to flight.[18] Fleeing back to Normandy, Philip avenged himself on the English by attacking the forces of Prince John and the Earl of Arundel, seizing their baggage train.[18] By now both sides were tiring, and they agreed to the temporary Truce of Tillières.

War continued in 1195 with Philip once again besieging Verneuil. Richard arrived to discuss the situation face to face. During negotiations, Philip secretly continued his operations against Verneuil; when Richard found out, he left, swearing revenge.[18] Philip now pressed his advantage in northeastern Normandy, where he conducted a raid at Dieppe, burning the English ships in the harbour while repulsing an attack by Richard at the same time. Philip now marched southward into the Berry region. His primary objective was the fortress of Issoudun, which had just been captured by Richard's mercenary commander, Mercadier. The French king took the town and was besieging the castle when Richard stormed through French lines and made his way in to reinforce the garrison, while at the same time another army was approaching Philip's supply lines. Philip called off his attack, and another truce was agreed to.[18]

The war slowly turned against Philip over the course of the next three years. Though things looked promising at the start of 1196 when Arthur of Brittany ended up in Philip's hands, and he won the Siege of Aumale, it would not last. Richard won over a key ally, Baldwin of Flanders, in 1197. Then in 1198, Henry the Holy Roman Emperor died, and his successor was to be Otto IV, Richard's nephew, who put additional pressure on Philip.[19] Finally, many Norman lords were switching sides and returning to Richard's camp. This was the state of affairs when Philip launched his 1198 campaign with an attack on the Vexin. He was pushed back and then had to deal with the Flemish invasion of Artois.

On 27 September, Richard entered the Vexin, taking Courcelles-sur-Seine and Boury-en-Vexin before returning to Dangu. Philip, believing that Courcelles was still holding out, went to its relief. Discovering what was happening, Richard decided to attack the French king's forces, catching Philip by surprise.[19] Philip's forces fled and attempted to reach the fortress of Gisors. Bunched together, the French knights and Philip attempted to cross the Epte River on a bridge that promptly collapsed under their weight, almost drowning Philip in the process. He was dragged out of the river and shut himself up in Gisors.[19]

Philip soon began a new offensive, launching raids into Normandy and again targeting Évreux. Richard countered Philip's offensive with a counterattack in the Vexin, while Mercadier led a raid on Abbeville. The upshot was that by the fall of 1198, Richard had regained almost all that had been lost in 1193.[19] Philip, now in desperate circumstances, offered a truce so that discussions could begin towards a more permanent peace, with the offer that he would return all of the territories except for Gisors.

In mid-January 1199, the two kings met for a final meeting, Richard standing on the deck of a boat, Philip standing on the banks of the Seine River.[20] Shouting terms at each other, they could not reach agreement on the terms of a permanent truce, but they did agree to further mediation, which resulted in a five-year truce that held. Later in 1199, Richard was killed during a siege involving one of his vassals.

Conflict with King John 1200–1206

In May 1200, Philip signed the Treaty of Le Goulet with Richard's successor John, King of England. The treaty was meant to bring peace to Normandy by settling the issue of its much-reduced boundaries and the terms of John's vassalage for it, Anjou, Maine, and Touraine. John agreed to heavy terms, including the abandonment of all the English possessions in Berry and 20,000 marks of silver, while Philip in turn recognised John as king, formally abandoning Arthur I of Brittany, whom he had thitherto supported, and he recognised John's suzerainty over the Duchy of Brittany. To seal the treaty, a marriage between Blanche of Castile, John's niece, and Louis the Lion, Philip's son, was contracted.

This did not stop the war, however, as John's mismanagement of Aquitaine led to the province erupting in rebellion later in 1200, which Philip secretly encouraged.[21] To disguise his ambitions, he invited John to a conference at Andely and then entertained him at Paris, and both times he committed to complying with the Treaty.[21] In 1202, disaffected patrons petitioned the French king to summon John to answer their charges in his capacity as John's feudal lord in France, and, when the English king refused to appear, Philip again took up the claims of Arthur, to whom he betrothed his six-year-old daughter, Marie. John crossed over into Normandy and his forces soon captured Arthur, and in 1203, the young man disappeared, with most people believing that John had had Arthur murdered. The outcry over Arthur's fate saw an increase in local opposition to John, which Philip used to his advantage.[21] He took the offensive and, apart from a five-month siege of Andely, he swept all before him. On the fall of Andely, John fled to England, and by the end of 1204, most of Normandy and the Angevin lands, including much of Aquitaine had fallen into Philip's hands.[21]

What Philip had gained through victory in war, he then sought to confirm by legal means. Philip, again acting as John's liege lord over his French lands, summoned him to appear before the Court of the Twelve Peers of France, to answer for the murder of Arthur of Brittany.[22] John requested safe conduct, but Philip only agreed to allow him to come in peace, while providing for his return only if it were allowed after the judgment of his peers. Not willing to risk his life on such a guarantee, John refused to appear, so Philip summarily dispossessed him of his French lands.[22] Pushed by his barons, John eventually launched an invasion in 1206, disembarking with his army at La Rochelle during one of Philip's absences, but the campaign was a disaster.[22] After backing out of a conference that he himself had demanded, John eventually bargained at Thouars for a two-year truce, the price of which was his agreement to the chief provisions of the judgment of the Court of Peers, including the loss of his patrimony.[22]

Alliances against Philip 1208–1213

In 1208, Philip of Swabia, the successful candidate for becoming the next emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, was assassinated, meaning that the imperial crown was given to his rival, Otto IV, the nephew of King John. Otto, prior to his accession, had promised to help John to recover his lost European possessions, but circumstances prevented them from making good their claims.[23] By 1212, both John and Otto were engaged in power struggles against Pope Innocent III, John over his refusal to accept the papal nomination for the Archbishop of Canterbury, and Otto over his attempt to strip Frederick II of his Sicilian crown. Philip decided to take advantage of this situation, firstly in Germany where he supported the rebellion of the German nobility in support of the young Frederick.[23] John immediately threw his support behind Otto, and Philip now saw his chance to launch a successful invasion of England.

In order to secure the cooperation of all his vassals in his plans for the invasion, Philip denounced John as an enemy of the Church, thereby justifying his attack against him as being solely for religious reasons. He summoned an assembly of French barons at Soissons, which was well attended with the exception of Ferdinand, Count of Flanders. He refused to attend, still angry over the loss of the towns of Aire and Saint-Omer which had been captured by Philip's son, Louis the Lion, and he would not participate in any campaign until they had been restored to him.[23]

In the meantime, Philip, eager to prove his loyalty to Rome and thus secure Papal support for his planned invasion, announced at Soissons his reconciliation with his estranged wife Ingeborg of Denmark which the Popes had been pushing.[23] The Barons fully supported his plan, and they all gathered their forces and prepared to join with Philip at the agreed rendezvous. In all this, Philip remained in constant communication with Pandolfo, the Papal Legate, who was encouraging Philip to pursue his objective. Pandolfo however was also holding secret discussions with King John. Advising the English King of his precarious predicament, he persuaded John to abandon his opposition to Papal investiture and agreed to accept the Papal Legate's decision in any ecclesiastical disputes as final.[24] In return, the Pope agreed to accept the Kingdom of England and the Lordship of Ireland as Papal fiefs, which John would rule as the Pope's vassal, and for which John would do homage to the Pope.[24]

No sooner had the treaty been ratified in May 1213 than Pandolfo announced to Philip that he would have to abandon his expedition against John, since to attack a faithful vassal of the Holy See would constitute a mortal sin. In vain did Philip argue that his plans had been drawn up with the consent of Rome, that his expedition was in support of papal authority which he only undertook on the understanding that he would gain a Plenary Indulgence, or that he had spent a fortune preparing for the expedition. The Papal Legate remained unmoved,[24] but Pandolfo did suggest an alternative. The Count of Flanders had denied Philip's right to declare war on England while King John was still excommunicated, and that his disobedience needed to be punished.[24] Philip eagerly accepted the advice, and quickly marched at the head of his troops into the territory of Flanders.

Battle of Bouvines 1214

The French fleet, reportedly numbering some 1,700 ships,[25] proceeded first to Gravelines and then to the port of Dam. Meanwhile the army marched by Cassel, Ypres, and Bruges before laying siege to Ghent.[25] Hardly had the siege begun when Philip learned that the English fleet had captured a number of his ships at Dam and that the rest were so closely blockaded in its harbor that it was impossible for them to escape. After having obtained 30,000 marks as a ransom for the hostages he had taken from the Flemish cities he had captured, Philip quickly retraced his steps to reach Dam. It took him two days, arriving in time to relieve the French garrison,[25] but he discovered he could not rescue his fleet. He ordered it to be burned to prevent it from falling into enemy hands, then he commanded the town of Dam to be burned to the ground as well. Determined to make the Flemish pay for his retreat, in every district he passed through he ordered that all towns be razed and burned, and that the peasantry be either killed or sold as slaves.[25]

The destruction of the French fleet had once again raised John's hopes, so he began preparing for an invasion of France and a reconquest of his lost provinces. His barons were initially unenthusiastic about the expedition, which delayed his departure, so it was not until February 1214 that he disembarked at La Rochelle.[25] John was to advance from the Loire, while his ally Otto IV made a simultaneous attack from Flanders, together with the Count of Flanders. Unfortunately, the three armies could not coordinate their efforts effectively. It was not until John had been disappointed in his hope for an easy victory after being driven from Roche-au-Moine and had retreated to his transports that the Imperial Army, with Otto at its head, assembled in the Low Countries.[25]

On 27 July 1214, the opposing armies suddenly discovered they were in close proximity, on the banks of a little tributary of the River Lys, near the Bridge of Bouvines. Philip's army numbered some 15,000, while the allied forces possessed around 25,000 troops. The armies clashed at the Battle of Bouvines, a tight battle. Philip was unhorsed by the Flemish pikemen in the heat of battle, and were it not for his plate mail armor he would have probably been killed.[26] When Otto was carried off the field by his wounded and terrified horse,[26] and Ferdinand, Count of Flanders, was severely wounded and captured by the French, the Flemish and Imperial troops saw that the battle was lost, turned, and fled from the field. The French troops began pursuing them, but with night approaching, and with the prisoners they already had too numerous and, more importantly, too valuable to risk in a pursuit, Philip ordered a recall before his troops had moved little more than a mile from the battlefield.[26] Philip returned to Paris triumphant, marching his captive prisoners behind him in a long procession, as his grateful subjects came out to greet the victorious king. In the aftermath of the battle, Otto retreated to his castle of Harzburg and was soon overthrown as Holy Roman Emperor, to be replaced by Frederick II. Count Ferdinand remained imprisoned following his defeat, while King John obtained a five-year truce, on very lenient terms given the circumstances.[26]

Philip's decisive victory was crucial in ordering Western European politics in both England and France. In England, the defeated John was so weakened that he was soon required to submit to the demands of his barons and sign the Magna Carta, limiting the power of the crown and establishing the basis for common law. In France, the battle was instrumental in forming the strong central monarchy that would characterise its rule until the first French Revolution. It was also the first battle in the Middle Ages in which the full value of infantry was realised.[26]

A large scale mural of Battle of Bouvines by painter Horace Vernet is featured in the Galerie des Batailles at Versailles. Philip is shown in the center with Henry II of England bowing, Ferdinand, Count of Flanders next to him along with Otto IV, Holy Roman Emperor of Germany.

Marital problems

After Isabelle's early death in childbirth, in 1190, Philip decided to marry again. On 15 August 1193, he married Ingeborg (1175–1236), daughter of King Valdemar I of Denmark (ruled 1157–82). She was renamed Isambour, and Stephan of Dornik described her as "very kind, young of age but old of wisdom." For some unknown reason, Philip was repelled by her and he refused to allow her to be crowned queen. Ingeborg protested at this treatment; his response was to confine her to a convent. He then asked Pope Celestine III for an annulment on the grounds of non-consummation. Philip had not reckoned with Isambour, however; she insisted that the marriage had been consummated, and that she was his wife and the rightful queen of France. The Franco-Danish churchman William of Paris intervened on the side of Ingeborg, drawing up a genealogy of the Danish kings to disprove the alleged impediment of consanguinity.

In the meantime Philip had sought a new bride. Initially agreement had been reached for him to marry Margaret of Geneva, daughter of William I, Count of Geneva, but the young bride's journey to Paris was interrupted by Thomas I of Savoy, who kidnapped Philip's intended new queen and married her instead, claiming that Philip was already bound in marriage. Philip finally achieved a third marriage, on 7 May 1196, to Agnes of Merania from Dalmatia (c. 1180 – 29 July in 1201). Their children were Marie (1198 – 15 October in 1224) and Philippe Hurepel (1200–1234), Count of Clermont and eventually, by marriage, Count of Boulogne.

Pope Innocent III (ruled 1198–1216) declared Philip Augustus's marriage to Agnes of Merania null and void, as he was still married to Isambour. He ordered the King to part from Agnès; when he did not, the Pope placed France under an interdict in 1199. This continued until 7 September 1200. Due to pressure from the Pope and from Ingeborg's brother, King Valdemar II of Denmark (ruled 1202–41), Philip finally took Isambour back as his wife in 1213.

Issue

- By Isabella of Hainaut:

- Louis (3 September 1187 – 8 November 1226), King of France (1223-1226); married Blanche of Castile and had issue.

- Robert (15 March 1190 – 18 March 1190)

- Philip (15 March 1190 – 18 March 1190)

- By Agnes of Merania:

- Marie (1198 – 15 August 1238); married firstly Philip I of Namur, had no issue. Married secondly Henry I of Brabant, had issue.

- Philip (July 1200 – 14/18 January 1234), Count of Boulogne by marriage; married Matilda II, Countess of Boulogne and had issue.

Last years

Philip turned a deaf ear when the Pope asked him to do something about the heretics in the Languedoc. When Pope Innocent III called for a crusade against the Albigensians, or Cathars, in 1208, Philip did nothing to support it, though he did not stop his nobles from joining.[27] The war against the Cathars did not end until 1244, when their last strongholds were finally captured. The fruits of the victory, the submission of the south of France to the crown, were to be reaped by Philip's son, Louis VIII, and grandson, Louis IX, the successive kings of France.[28] From 1216 to 1222 Philip also arbitrated in the War of Succession in Champagne and finally helped the military efforts of Eudes III, Duke of Burgundy, and Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, to bring it to an end.

Philip II Augustus would play a significant role in one of the greatest centuries of innovation in construction and in education. With Paris as his capital, he had the main thoroughfares paved, built a central market, Les Halles, continued the construction begun in 1163 of Notre-Dame de Paris, constructed the Louvre as a fortress, and gave a charter to the University of Paris in 1200. Under his guidance, Paris became the first city of teachers the medieval world had known. In 1224, the French poet Henry d'Andeli wrote of the great wine tasting competition that Philip II Augustus commissioned, the Battle of the Wines.

Philip II Augustus died 14 July 1223 at Mantes-la-Jolie and was interred in Saint Denis Basilica. Philip's son by Isabelle de Hainaut, Louis VIII, was his successor.

Portrayal in fiction

- King Philip appears in William Shakespeare's historical play The Life and Death of King John.

- King Philip also appears in James Goldman's 1966 Broadway Production of The Lion in Winter and was portrayed by Christopher Walken, as well as the 1968 Academy Award winning film of the same name, with Timothy Dalton playing the role. In the 2003 remake starring Patrick Stewart and Glenn Close, he is played by Jonathan Rhys Meyers.

- King Philip also appears in the Ridley Scott's 2010 movie Robin Hood.

- King Philip appears in Sharon Kay Penman's novels The Devil's Brood and Lionheart.

- King Philip appears in Judith Koll Healey's novel The Rebel Princess.

- King Philip appears in the game Stronghold Crusader. He is portrayed as a somewhat weak ruler who is rather reckless in battle with his knights.

- King Philip appears in the game Genghis Khan II: Clan of the Gray Wolf as the head of the Capetian dynasty. He is the only ruler with an A in politics and a B in everything else.

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Philip II of France | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- ↑ Cullum, P. H.; Lewis, Katherine J., eds. (2004). Holiness and masculinity in the Middle Ages. University of Wales Press - Religion and Culture in the Middle Ages. University of Wales Press. p. 135. ISBN 9780708318942. Retrieved 2012-11-22.

[...] Philip Augustus 'Dieudonne', [...] as this epithet demonstrates, was thought to have been given to Louis VII by God, because Louis had been married three times and had to wait many years for the birth of a son.

- ↑ Smedley (1836), p. 52

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Smedley (1836), p. 55

- ↑ Smedley (1836), p. 56

- ↑ J. Bradbury, Philip Augustus: King of France 1180–1223, 252

- ↑ J. Bradbury, Philip Augustus: King of France 1180–1223, 280

- ↑ J. Bradbury, Philip Augustus: King of France 1180–1223, 242

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Smedley (1836), p. 57

- ↑ J. Bradbury, Philip Augustus: King of France 1180–1223, 245

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 "Philip II." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica 2008 Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2008

- ↑ Baldwin 1991, p. 3

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Smedley (1836), p. 58

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Rees (2006), p. 1

- ↑ Smedley (1836), p. 62

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Smedley (1836), p. 63

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Rees (2006), p. 2

- ↑ Smedley (1836), p. 64

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 Rees (2006), p. 3

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Rees (2006), p. 4

- ↑ Rees (2006), p. 5

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Smedley (1836), p. 67

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Smedley (1836), p. 68

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Smedley (1836), p. 69

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 Smedley (1836), p. 70

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 25.5 Smedley (1836), p. 71

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 Smedley (1836), p. 72

- ↑ Rodney Stark, For the glory of God, (Princeton University Press, 2003), 56.

- ↑ Jill N. Claster, Sacred Violence: The European Crusades to the Middle East, 1095-1396, (University of Toronto Press, 2009), 220.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Philip II of France. |

- Baldwin, John W. (1991), The Government of Philip Augustus: Foundations of French Royal Power in the Middle Ages, University of California Press, ISBN 0520073916

- Meade, Marion. Eleanor of Aquitaine: A Biography. New York: Hawthorn Books, 1977. ISBN 0-8015-2231-5

- Richard, Jean. "Philippe Auguste, la croisade et le royaume." in Idem, Croisés, Missionaires et Voyageurs. Perspectives Orientales du Monde Latin Médiéval (London: Variorum, 1983) (Variorum Collected Studies Series CS182).

- Payne, Robert. The Dream and the Tomb: A History of the Crusades. New York: Stein and Day, 1984. ISBN 0-8128-2945-X

- Rees, Simon. King Richard I of England Versus King Philip II Augustus. Military History Magazine, September 2006

- Smedley, Edward. The History of France, from the final partition of the Empire of Charlemagne to the Peace of Cambray. London: Baldwin and Cradock, 1836.

- "The 'War' of Bouvines (1202–1214)". Retrieved 29 September 2008.

| Philip II of France Born: 21 August 1165 Died: 14 July 1223 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Louis VII |

King of the Franks 1 November 1179 – 1190 with Louis the Young as senior king (1 November 1179 – 18 September 1180) |

Changed title |

| New title | King of France 1190 – 14 July 1223 |

Succeeded by Louis VIII |

| Count of Artois 28 April 1180 – 15 March 1190 with Isabelle | ||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||