Phantasm (film)

| Phantasm | |

|---|---|

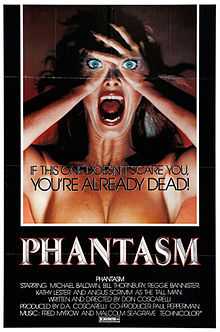

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Don Coscarelli |

| Produced by | Don Coscarelli |

| Written by | Don Coscarelli |

| Starring |

|

| Music by |

|

| Cinematography | Don Coscarelli |

| Edited by | Don Coscarelli |

Production company |

New Breed Productions |

| Distributed by | AVCO Embassy Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 89 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $300,000[2] |

| Box office | $12 million[3] |

Phantasm is a 1979 American horror film directed, written, photographed, co-produced, and edited by Don Coscarelli. It introduces the Tall Man (Angus Scrimm), a supernatural and malevolent undertaker who turns the dead into dwarf zombies to do his bidding and take over the world. He is opposed by a young boy, Mike (Michael Baldwin), who tries to convince his older brother Jody (Bill Thornbury) and family friend Reggie (Reggie Bannister) of the threat.

Phantasm was a locally financed independent film; the cast and crew were mostly amateurs and aspiring professionals. Though initial reviews were mixed, it became a cult film; both positive and negative reviews focused on the dream-like, surreal narrative and imagery. It has appeared on several critics' lists of best horror films, and it has been cited as an influence on later horror series. It was followed by three sequels: Phantasm II (1988), Phantasm III: Lord of the Dead (1994), and Phantasm IV: Oblivion (1998). The last two were released direct-to-video. In 2014, a fourth sequel titled Phantasm V: Ravager (2014) was announced.[4]

Plot

Following the death of his parents, 24-year-old musician Jody Pearson raises his 13-year-old brother Mike in a small town disturbed by the mysterious deaths of its citizens. Reggie, a family man and ice cream vendor, joins the brothers in their suspicions that the local mortician, dubbed the Tall Man, is responsible for the deaths. Mike relays his fears to a fortune teller and her granddaughter about the possibility of Jody departing and leaving him in the care of his aunt, along with his suspicions about the Tall Man. Mike is shown a small black box and told to put his hand into it. After the box grips his hand, Mike is told not to be afraid, and, as the panic subsides, the box relaxes its grip. The notion of fear itself as the killer is established, propelling Mike toward his final confrontation with the Tall Man.

Minions of the Tall Man, deceased townspeople who are shrunk down to dwarf size and reanimated, pursue Mike after he investigates further. After convincing Jody and Reggie, who are initially skeptical of his stories, they find a strange white room with containers in the mausoleum. Mike discovers a gateway to another planet, which he enters briefly; there, he sees the dwarves that have hunted him being used as slaves. While trying to escape the Tall Man, Reggie is stabbed and appears to die, and Mike and Jody barely escape. They devise a plan to lure the Tall Man into a local deserted mine shaft and trap him inside. After doing so successfully, Mike wakes with a start in his house, lying by the fireplace.

Reggie, who is sitting beside him, tells Mike he was simply having a nightmare, something that has been a common occurrence since Jody died in a car crash. When Mike enters his bedroom, he is shocked to see the Tall Man is waiting behind the door. In the final scene, one of the Tall Man's dwarf minions pulls Mike through his bedroom mirror.

Cast

- After being intimidated by Scrimm on the set of a previous film, Coscarelli decided that Scrimm would make a great villain.[5] Initially, Scrimm had little input into the character, but he made more of a contribution as Coscarelli began to trust his instincts. Scrimm was outfitted in lifts and a suit too small for him in order to make him seem even taller and skinnier. Coscarelli says of Scrimm, "I really didn't have any idea that he would take it to the level that he did. ... I could see it was going to be a very powerful character."[6]

- A. Michael Baldwin as Mike Pearson:

- After the deaths of his parents, Mike tries to convince his brother and Reggie that a local mortician called the Tall Man is responsible for their deaths. Coscarelli attributes the enduring popularity of the film to young audiences who respond to Mike's adventures.[6] After they worked together in a prior film, Coscarelli wrote a film in which Baldwin could star.[7]:51

- Bill Thornbury as Jody Pearson:

- Jody is Mike's older brother. After their parents die, Jody becomes Mike's guardian, but Jody confides in his friends that he's uncomfortable with the responsibility.

- Don Coscarelli based the character of Reggie on his friend Reggie Bannister, for whom the role was written; they then twisted the character into new directions.[8] Reggie was designed to be an everyman,[8] a loyal friend,[9] and the comic relief.[10]

- Kathy Lester as Lady in Lavender:

- The Tall Man appears in the form of the Lady in Lavender,[11] which he uses to seduce and kill Tommy, Jody's friend. Laura Mann appears as Kathy Lester's double, credited as Double Lavender.

Bill Cone portrays Tommy, Mary Ellen Shaw the fortune-teller, and Terrie Kalbus the fortune-teller's granddaughter.

Themes

John Kenneth Muir states that the film is about mourning and death.[12] Many of the film's fans are young boys, aged 10–13. According to Angus Scrimm, the film "gives expression to all their insecurities and fears". Scrimm states that the theme of loss and how, by fantasizing about death, the young protagonist deals with the deaths in his family drives the story.[6] Coscarelli identifies it as a "predominately male story" that young teens respond to.[5] Scrimm explains the popularity of the film as fans responding to themes of death,[5] and the Tall Man himself represents death.[6] Muir describes the Tall Man as embodying childhood fears of adults and states that the Tall Man wins in the end because dreams are the only place where death can be defeated.[12] American views of death are another theme:

I had a compunction to try to do something in the horror genre and I started thinking about how our culture handles death; it’s different than in other societies. We have this central figure of a mortician. He dresses in dark clothing, he lurks behind doors, they do procedures on the bodies we don’t know about. The whole embalming thing, if you ever do any research on it, is pretty freaky. It all culminates in this grand funerary service production. It’s strange stuff. It just seemed like it would be a great area in which to make a film.

Dreams and surrealism are also an important part of Phantasm. Marc Savlov of the Austin Chronicle compares Phantasm to the works of Alejandro Jodorowsky and Luis Buñuel in terms of weirdness. Savlov describes the film as existentialist horror and "a truly bizarre mix of outlandish horror, cheapo gore, and psychological mindgames that purposefully blur the line between waking and dreaming."[5] Gina McIntyre of the Los Angeles Times describes the film as surreal, creepy, and idiosyncratic.[6] Muir writes that Phantasm "purposely inhabits the half-understood sphere of dreams" and takes place in the imagination of a disturbed boy.[12]

Production

After seeing the audience reaction to jump scares in Kenny and Company, writer/director Don Coscarelli decided to do a horror film as his next project.[13] His previous films had not performed well, and he heard that horror films were always successful; branching into horror allowed him to combine his childhood love of the genre with better business prospects.[14] The original idea was inspired by Something Wicked This Way Comes by Ray Bradbury. Coscarelli had initially sought to adapt the story to film, but the license had already been sold.[15] The theme of a young boy's difficulty convincing adults of his fears was influenced by Invaders from Mars (1953).[16] Dario Argento's Suspiria (1977) and its lack of explanations was another influence on Coscarelli.[14] The soundtrack was influenced by Goblin and Mike Oldfield. The synthesizers were so primitive that it was difficult to repeat sounds.[17] When writing the film's conclusion, Coscarelli intentionally wanted to shock audiences and "send people out of the theater with a bang."[18]

There were no accountants on the set, but Coscarelli estimates the budget at $300,000.[6] Funding for the film came in part from Coscarelli's father;[19] additional funding came from doctors and lawyers.[6] His mother designed some of the special effects,[19] costumes, and make-up.[6] The cast and crew were composed mainly of friends and aspiring professionals. Due to their inexperience, they did not realize that firing blanks could be dangerous; Coscarelli's jacket caught fire from a shotgun blank.[6] Casting was based on previous films that Coscarelli directed, and he created roles for those actors.[15] Because he could not afford to hire an editor or cameraman, Coscarelli did these duties himself.[7]:50

Filming was done weekends and sometimes lasted for 20 hours over the course of more than a year.[5] Reggie Bannister described the production as "flying by the seat of our pants". The actors would be called to perform their scenes and picked up as soon as they were available.[6][9] Bannister did many of his own stunts.[9] Shooting took place primarily in in the San Fernando Valley in Chatsworth.[6] The script changed often during production, and Bannister says that he never saw a completed copy of it; instead, they worked scene-by-scene and used improvisation.[9][5] The script was characterized by Coscarelli as "barely linear".[14] While it contained the basic concepts of the completed film, the script was unfocused and rewritten during filming.[14] The spheres came from one of Coscarelli's nightmares, but the original idea did not involve drilling.[5] Will Greene, an elderly metal-worker, fashioned the iconic spheres, but he never got to see the finished film, as he died before the film was released.[18] The black 1971 Plymouth Barracuda was used because Coscarelli had known someone in high school who drove one; he realized that he could get his hands on one by using it in the film.[6]

Post-production took another six to eight months.[6] The first test screening was a disaster due to the length; Coscarelli says that he erred in adding too much character development, which needed to be edited out.[5] Phantasm 's fractured dream logic was due in part to the extensive editing.[17] During shooting, they did not have a clear idea of the ending.[14] Several endings were filmed, and one of them was re-used in Phantasm IV: Oblivion. Coscarelli attributed the freedom to choose from among these endings to his independent financing.[6]

Deleted scenes

In 1998, MGM re-released Phantasm on VHS and DVD with a newly remastered Dolby stereo soundtrack. Both the VHS and DVD releases included two deleted scenes:

- Mike enters a room with two coffins: one is open with a body inside and the other is closed. Mike hears sounds from inside the second coffin and thinks that Reggie is trapped inside; however, Reggie enters the room while Mike is trying to pry the coffin open. Mike realizes that something unpleasant is in the coffin, and he and Reggie close it. Mike suggests that they find Jody. This scene is not included on the Anchor Bay release.

- Mike and Jody encounter the Tall Man in the funeral home. Jody shoots the Tall Man several times with his shotgun, but it has no effect on him. The Tall Man knocks Mike onto the floor and picks up Jody by the neck with one hand. Mike sees a fire extinguisher and remembers that the Tall Man reacted badly when he passed by Reggie's Ice Cream truck with its refrigerator open. Realizing the Tall Man can be hurt by cold, Mike takes out the fire extinguisher and blasts the Tall Man with it. The Tall Man writhes in pain and screams, then his head explodes.

Release

To solicit outside opinions, Coscarelli paid an audience to watch an early cut of the film. Although Coscarelli called the result "a disaster", he was encouraged by the audience's reactions to the film.[18] The original theatrical release was June 1, 1979. It grossed $11,988,469 at the box office.[3] MGM released Phantasm on laserdisc in November 1995[20] and on DVD in August 1998.[21] Anchor Bay Entertainment re-released it on DVD on April 10, 2007.[22]

Reception and legacy

On Rotten Tomatoes, a review aggregator, 64% of 36 surveyed critics gave it a positive review, and the average rating is 6.3/10.[23] In a mostly negative review, Roger Ebert described the film as "a labor of love, if not a terrifically skillful one".[24] Trevor Johnston of Time Out called the film "a surprisingly shambolic affair whose moments of genuine invention stand out amid the prevailing incompetence."[25] Dave Kehr of the Chicago Reader described it as "spotty" and "effective here and there", though he praised Coscarelli's raw ability.[26] Vincent Canby of the New York Times compared it to a ghost story told by a bright, imaginative 8-year-old; he concluded that it is "thoroughly silly and endearing".[27] Kim Newman of Empire called it "an incoherent but effective horror picture" that "deliberately makes no sense" and rates it four out of five stars.[28] Variety gave it a positive review that highlighted the use of both horror and humor.[29] Scott Weinberg of Fearnet stated the acting is "indie-style raw" and special effects are sometimes poor, but the originality and boldness make up for it.[30] Steve Barton of Dread Central rated it five out of five stars and said the film is a masterpiece and "one hell of a scary film".[31] Bloody Disgusting rated the film four out of five stars and said the film is "truly original" and "imbues in its viewers is a profound sense of dread".[32] John Kenneth Muir called the film striking, distinctive, and original. Muir stated that the film has become a classic, and the Tall Man is a horror film icon.[12]

The film was rated #25 on the cable channel Bravo!'s list of The 100 Scariest Movie Moments.[33] It also placed #75 in Time Out London's 100 best horror films.[34] Drive-in movie critic Joe Bob Briggs included it at #20 in his 25 Scariest DVDs Ever list.[35] UGO placed the film (and the Tall Man) at #7 out of 11 in its Top Terrifying Supernatural Moments.[36] Phantasm has become a cult film;[5] Coscarelli attributes its cult following to nostalgia and its lack of answers, as repeated viewings can leave fans with different interpretations.[14] USA Today described three characteristics that make it a cult film: "the touching portrayal of two brothers in danger, an iconic villain in The Tall Man (Angus Scrimm) and a floating metallic sphere that's a death-dealing weapon."[2]

USA Today quoted Jovanka Vuckovic, editor in chief of Rue Morgue, as stating that Supernatural, A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), and One Dark Night (1983) were all influenced by Phantasm.[2]

Awards

- Don Coscarelli won the Special Jury Award in 1979 at the Avoriaz Fantastic Film Festival and the film was nominated for the Saturn Award for Best Horror Film in 1980.

References

- ↑ "PHANTASM (X)". British Board of Film Classification. 1979-04-26. Retrieved 2012-01-17.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Snider, Mike (2007-07-09). "'Phantasm' up for Grabs". USA Today. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Phantasm". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

- ↑ Dickson, Evan (2014-03-27). "[Exclusive Interview] Talking 'Phantasm: Ravager' With Creator Don Coscarelli! How Did They Keep It A Secret And When Will It Be Released?!". Bloody Disgusting. Retrieved 2014-03-31.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 Savlov, Marc (2000-03-31). "Sphere of Influence". Austin Chronicle. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 6.9 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 McIntyre, Gina (2009-10-16). "Happy Birthday, Tall Man! 'Phantasm' Turns 30". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Baldassarre, Angela (1999). The Great Dictators: Interviews with Filmmakers of Italian Descent. Guernica Editions. ISBN 9781550710946. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Yapp, Nate (2008-11-25). "Reggie Bannister ("Phantasm") Interview". classic-horror.com. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Johnson, Steve (2009-07-28). "30 Years of Phantasm". Icon vs Icon. Retrieved 2013-08-13.

- ↑ Hennessey, Cristopher; McCarty, Michael. "The Phantasm Man". More Giants of the Genre. Wildside Press. p. 79. ISBN 9787770047060. Retrieved 2013-08-08.

- ↑ Newman, Kim (2011). Nightmare Movies. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 278. ISBN 9781408817506. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Muir, John Kenneth (2002). Horror Films of the 1970s. McFarland. pp. 611–613. ISBN 9780786491568. Retrieved 2013-08-14.

- ↑ Yapp, Nate (2008-11-25). "Reggie Bannister ("Phantasm") Interview". Classic-Horror.com. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 Sutton, David (2006). "Don Coscarelli". Fortean Times. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 McCabe, Joseph (2007-04-09). "Don Coscarelli Talks Phantasm and Bubba". Fearnet. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

- ↑ Piepenburg, Erik (2013-01-24). "Just So You Know: ‘John Dies at the End’". New York Times. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Gilchrist, Todd (2007-04-10). "Exclusive Interview: Don Coscarelli". IGN. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Duvoli, John (1984-02-26). "'Cult' films Spell Success for Movie-Maker". The Evening News (Newburgh, New York). Retrieved 2014-03-05.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Pace, Dave (2013-04-11). "Q&A: Don Coscarelli on "JOHN DIES" & Independent Filmmaking for 30+ Years". Fangoria. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

- ↑ Simels, Steve (1995-11-10). "Phantasm; Re-Animator (1995)". Entertainment Weekly (300). Retrieved 2014-03-05.

- ↑ "New on Video". Star-News. 1998-08-28. Retrieved 2014-03-05.

- ↑ Jane, Ian (2007-04-10). "Phantasm". DVD Talk. Retrieved 2014-03-05.

- ↑ "Phantasm". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (1979-03-28). "Phantasm". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

- ↑ Johnston, Trevor. "Phantasm". Time Out. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

- ↑ Kehr, Dave. "Phantasm". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

- ↑ Canby, Vincent (1979-06-01). "Phantasm". New York Times. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

- ↑ Newman, Kim. "Phantasm". Empire. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

- ↑ Variety Staff. "Review: Phantasm". Variety. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

- ↑ Weinberg, Scott (2007-04-12). "Phantasm (1979)". Fearnet. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

- ↑ Barton, Steve (2007-04-08). "Phantasm: The Anchor Bay Collection (DVD)". DreadCentral. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

- ↑ Bloody Disgusting Staff. "Phantasm". Bloody Disgusting. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

- ↑ "The 100 Scariest Movie Moments". Bravo. Archived from the original on 2004-11-02. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

- ↑ "100 Best Horror Films". Time Out London. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

- ↑ Joe Bob Briggs (2005). Giant (October/November 2005). Cited on The Official Home of Joe Bob Briggs. Retrieved 2013-08-14.

- ↑ Cornelius, Ted (2008-07-22). "Top Terrifying Supernatural Moments". UGO. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

External links

- Official website

- Phantasm at the Internet Movie Database

- Phantasm at the TCM Movie Database

- Phantasm at AllMovie

- Phantasm at Box Office Mojo

- Phantasm at Rotten Tomatoes

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||