Phan Xích Long

| Phan Xích Long 潘赤龍 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

1893 Southern Vietnam |

| Died |

February 22, 1916 (aged 23) Saigon, Cochinchina (Vietnam) |

| Other names | Hồng Long, Phan Phát Sanh |

| Organization | Greater Ming State (self-styled) |

|

Notes Claimed to be the Emperor of Vietnam | |

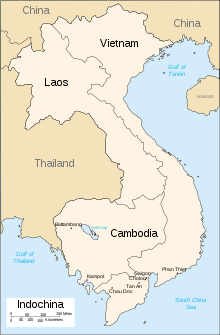

Phan Xích Long, also known as Hồng Long, born Phan Phát Sanh (1893–1916), was a 20th-century Vietnamese mystic and geomancer who claimed to be the Emperor of Vietnam. He attempted to exploit religion as a cover for his own political ambitions, having started his own ostensibly religious organisation. Claiming to be a descendant of Emperor Hàm Nghi, Long staged a ceremony to crown himself, before trying to seize power in 1913 by launching an armed uprising against the colonial rule of French Indochina. His supporters launched an attack on Saigon in March 1913, drinking potions that purportedly made them invisible and planting bombs at several locations. The insurrection against the French colonial administration failed when none of the bombs detonated and the supposedly invisible supporters were apprehended.

The French authorities imprisoned Long and many of his supporters, who openly admitted their aim of overthrowing French authorities at the trial. During the 1916 Cochinchina uprisings against French rule, many of Long's supporters attempted to break him out of jail. The French easily repelled the attack on the jail, decimating Long's movement. Following the attempted breakout, Long and his key supporters were put to death. Many of the remnants of his support base went on to join what later became the Cao Đài, a major religious sect in Vietnam.

Early career

Long was born in 1893 in southern Vietnam as Phan Phát Sanh. His place of birth is disputed; the historians R. B. Smith and Hue-Tam Ho Tai say that he was from Cholon, the Chinese business district of Saigon,[1][2] while Oscar Chapuis records Tan An as his place of birth.[3] Sanh's father was a police officer.[1][2][3][4] and it has been speculated that the family were of Chinese descent.[2] He started as a servant in a French family, before travelling to the That Son (Seven Mountains) region in the far south of Vietnam, a region that was known as a hotbed of mysticism. There Long trained in mysticism.[2] As a youth, Sanh travelled from Vietnam to Siam, earning his living as a fortune-teller and geomancer.[3][4]

In mid-1911, Sanh formed a secret society on the unverified pretense that he was a descendant of Hàm Nghi,[4] the boy emperor of the 1880s. Led by Tôn Thất Thuyết and Phan Đình Phùng—two high-ranking mandarins—Hàm Nghi's Cần Vương movement battled against French colonisation in the decade leading up to 1895. Their objective was to expel the French authorities and establish Ham Nghi as the emperor of an independent Vietnam. This failed, and the French exiled the boy emperor to Algeria, replacing him with his brother Đồng Khánh.[4] From then on, the French retained the monarchy of the Nguyễn Dynasty, exiling any emperors who rose against colonial rule and replacing them with more cooperative relatives.[5] Sanh also claimed descent from the Lê Dynasty, which ruled Vietnam in the 15th and 16th centuries. He was a strong warrior,[6] further presenting himself as the founder of China's Ming Dynasty.[7]

At the time of Sanh's activities in the 1910s, there were two members of the Nguyễn Dynasty who commanded respect among Vietnamese monarchists. The first was the boy emperor Duy Tân, who was himself deported in 1916 after staging an uprising.[8] Duy Tan's grandfather, Emperor Dục Đức, was the adopted son of the childless Emperor Tự Đức, the last independent emperor of Vietnam.[5] The second figure who was seen by Vietnamese as a possible leader of an independent monarchy was Prince Cường Để. Cường Để was a direct descendant of Emperor Gia Long, who had established the Nguyễn Dynasty and unified Vietnam in its modern state. Cường Để was a prominent anti-colonial activist who lived in exile in Japan.[4]

Sanh's two main assistants were Nguyen Huu Tri and Nguyen Van Hiep, whom he met at Tân Châu in Châu Đốc Province (now in An Giang Province). The trio agreed to plot an uprising against the French under the cover of a religious sect.[1] The genesis of their cooperation is unclear, but it may have started before mid-1911.[1] Tri and Hiep were said to have been in awe when Sanh produced a golden plaque that read "heir to the throne".[3] The men agreed that the geographical foci of their movement would be in Cholon and Tan An in Vietnam and Kampot in Cambodia.[1] The trio decided to model their actions on an uprising that had occurred in Kampot in 1909. On that occasion, a group of Cambodians of Chinese descent had marched into the town wearing white robes, claiming to be followers of a Battambang-based Cambodian prince who would overthrow French rule and lead them to independence.[1] After the formation of the sect, Sanh temporarily moved abroad, spending time in Siam and Cambodia.[2][3] During this time, he learned sorcery and magic, supplementing his mystical training with a military education. He learned pyrotechnics for the purpose of making fireworks and bombs.[3]

Coronation

Sanh returned to southern Vietnam, and began dressing as a Buddhist monk. He travelled through the six provinces of the Mekong Delta region.[4] His associates Hiep and Tri found an elderly man from Cholon in Saigon, and presented the senior citizen to the populace as a "living Buddha".[9][10] After some local elders objected to their activities, they moved to the centre of Cholon.[2] The old man took up residence with Sanh, and peasants and tradespeople soon began flocking to their makeshift temple, located in a house in Cholon's Thuan Kieu Street.[9][10] As their temple was located in a prominent commercial area, the group began to collect more funds. The donors made offerings of gold and silver, with some individual donations being worth as much as 1,500 piastres.[4] When the "living Buddha" unexpectedly died in February 1912, he was interred in the family shrine of a notable follower. Sanh's strategists declared that before the old man had died, he named Sanh as the rightful Emperor of Vietnam.[4] In the meantime, the old man's remains became the object of veneration, providing further cover for political plotting and fundraising when visitors came to pay their respects.[10] After the completion of the funeral rites, Sanh and his followers staged an impromptu coronation ceremony at Battambang in October 1912.[9] Sanh took on the name Phan Xích Long and was also known as Hồng Long, both of which mean "red dragon".[4]

Vast crowds of locals began flocking to pay homage to Long, vowing to contribute labour and finance in an effort to expel the French from Vietnam and install Long as the independent monarch. By this time, Long was claiming to have received a letter from Cuong De, which supposedly confirmed his royal descent. Long's followers spared no expense in decorating Long with royal accoutrements. They made a medallion inscribed "Phan Xích Long Hòang Đế" (Emperor Phan Xích Long) and a royal seal with a dragon's head with the words "Đại Minh Quốc, Phan Xích Long Hòang Đế, Thiên tử" (Greater Ming State, Emperor Phan Xích Long, Son of Heaven). The words "Đại Minh" were interpreted as either having arbitrarily been copied from local Chinese Vietnamese secret society slogans, or as a strategic ploy to invoke the names of the Ming Dynasty to appeal to the Chinese who had emigrated to Vietnam after the fall of the Ming. Long's supporters produced a sword with the inscription "Tiên đả hôn quân, hậu đả loạn thần" (First strike the debauched king, next the traitorous officials) and a ring inscribed "Dân Công" (Popular Tribute).[4] From then on, Long presented himself as the emperor and signed documents under the royal title.[6]

Long's strategy of proclaiming himself as a royal descendent or claiming to have supernatural powers in order to rally support for political ends was not new; it has been repeatedly used throughout Vietnamese history. In 1516, a man calling himself Trần Cảo rebelled against the Lê Dynasty, claiming to be a descendant of the deposed Trần Dynasty and a reincarnation of Indra.[11] During the 19th century, there was a Buddhist revival and many people masqueraded as monks claiming to have supernatural powers. These false monks were frequently able to start new religious movements and secret societies based on millenarianism. Quickly gathering large numbers of disciples, they staged rebellions against Vietnamese imperial and French colonial armies alike. However, these uprisings were typically incoherent and caused minimal disruption to the ruling authorities.[12][13] On the other hand, the French were often troubled by resistance movements in southern Vietnam that were led by more conventionally motivated nationalist militants, such as the guerrilla outfits of Trương Định and Nguyễn Trung Trực.[14][15]

Military buildup

During the time he spent in Battambang for the coronation, Long organised the construction of a pagoda in the town, and in December, he unsuccessfully applied for a land concession.[1] After the coronation, Long was taken to the That Son region in Châu Đốc, in the far south of the Mekong Delta. There the peasants built a temple for him. They used a small restaurant in a nearby village as a reception centre for the temple, as the temple was increasingly used as a military base, where fighters, weaponry and munitions were being assembled for an uprising.[16] In the village of Tan Thanh, a local leader recruited his peasants for Long's revolt. The village chieftain predicted that a new Vietnamese monarch would descend from the sky at Cholon in March 1913,[10] and that only the royalists would survive this miracle.[10]

Such proclamations were repeated across southern Vietnam and in Cambodia, and notices were posted in Saigon, Phnom Penh, the road between the cities, and in many community venues in rural communities.[17] Long's supporters presented them in the form of a royal edict on wooden blocks, declaring their intention to attack French military installations.[16] They called on the people to rise up and topple French rule and said that supernatural forces would aid the independence fighters, saying that an unnamed monk would arrive from the mountains to lead them.[17] At the time, southern Vietnam was beset by heavy corvée labour demands, especially with large-scale roadworks in progress. This meant that the peasants had less time to tend to their farmland, and revolts and strikes had been common.[17] The simmering discontent is seen as a reason for Long's ability to gather such levels of support in a short time.[17] Long's supporters called on merchants to flee and convert their colonial bank notes into solid copper cash.[16] Word of the planned revolt spread quickly, leading to a substantial depreciation in the currency.[17]

Long took the lead in preparing the explosives, telling his followers that his experience as a fortuneteller, mystic and natural healer made him an expert. The bombs were made from cannon shot, carbon, sulphur and saltpeter, which were then wrapped together.[16]

Failed uprising

On March 22, the French arrested Long in the coastal town of Phan Thiết, some 160 kilometres to the east of Saigon.[1][9] His activities and proclamations had attracted the attention of French colonial officials, and just days before, the Resident of Kampot visited the Battambang temple and spotted the collection of white robes, which were similarly styled to the uniforms worn during the 1909 uprising.[10] However, Long's disciples were unaware that he had been arrested and continued with their plot.[2] After nightfall on March 23, the bombs were taken into Saigon and placed at strategic points, with proclamation notices being erected in close proximity. None of the bombs successfully detonated.[4] One source says that the bombs failed because the French authorities had defused all of them after uncovering the conspiracy.[2]

On March 28, the second phase of the operation started when several hundred rebels marched into Saigon dressed all in white,[1] armed with only sticks and spears.[2] Before the march, they had ingested potions that purportedly made them invisible. However, the French military were able to capture more than 80 of the supposedly invisible rebels during demonstrations against French rule.[1][16] The police raided the homes of several people who were known to be involved with Long's plot, resulting in more arrests. They captured most of Long's main supporters, rendering the organisation impotent.[1] However, Tri managed to escape.[10]

Trial and imprisonment

Those involved were taken before a tribunal in November 1913, where the leaders freely stated their intentions of overthrowing the French colonial regime. Of the 111 people arrested, the tribunal convicted 104, of whom 63 received prison sentences.[2][10][16] During the trial, some community leaders wrote to the Governor-General of Indochina, blaming French oppression of the populace through corvee labour and the confiscation of land, for the discontent that led to the uprising.[18] The prosecutor also criticised the way in which colonial authorities operated.[18]

Ernest Outrey,[19] the French Governor of Cochinchina, the southern region of Vietnam, was known for his support of colonial enterprise and rigid rule of the colony. He was unmoved by claims that the uprising had been fuelled by a sense of injustice.[18] He said

Individually, the leaders of the movement have no personal motive to invoke in order to justify their xenophobic sentiments. Some of them are men who have remained imbued with the ancient order of things predating French conquest and who have adamantly remained within the tradition and ideas of the past; others are fanatics, who are persuaded that they are devoted to a noble cause.[18]

The governor went on to excoriate the French press for their criticism of colonial policy, claiming that they boosted the morale of anti-colonial activists.[18] The prosecutor thought that because Long's movement was affiliated with the Việt Nam Quang Phục Hội (VNQPH), an exiled monarchist organisation led by the leading anti-colonial activist Phan Bội Châu, and Cường Để.[18] The suspicion was based on the fact that the VNQPH had printed their own currency and circulated them into Vietnam at the same time that Long's monetary policy had led to a depreciation.[17] Cường Để had also secretly re-entered southern Vietnam and had been travelling through the countryside when Long's uprising was launched in March.[19] The prosecutor claimed that activists from northern and central Vietnam, the main source of the VNQPH's followers, were behind the plot.[18] The defendants denied this, asserting that most of the participants were "illiterate peasants",[20] while the VNQPH were dominated by members of the scholar-gentry.[18]

The French intended to deport Long to French Guiana,[20] but the outbreak of World War I in 1914 interrupted their plans. As a result, Long remained in Saigon Central Prison,[9] serving his life sentence with hard labour.[6] The French were unaware that Long was still in contact with his supporters.[20]

Attempted jailbreak and execution

Over time, resentment against French rule rose again, due to World War I. The colonial authorities had forced each village to send a quota of men to serve on the Western Front. In Vietnam, rumours circulated, claiming that France was close to defeat.[20] Believing that the colonial hold had been weakened by the strain of war in Europe, Vietnamese nationalists were buoyed.[20] In February 1916, uprisings broke out in southern Vietnam, with rebels demanding the restoration of an independent monarchy. One of their many objectives was to secure Long's release by breaking down Saigon prison,[21] and this was the most noted incident during the tumult.[20]

Attacks on prisons were not uncommon in French Indochina, as rebels often viewed the prisoners as a source of reinforcements. Georges Coulet, regarded as French Indochina's leading scholar on anti-French religious movements, said that "The attack on Saigon Central Prison was not simply an attempt to release the pseudo-Emperor, Phan Xich Long, but was intended to deliver all prisoners".[22]

Before daybreak on February 15, 1916,[9][10] between 100 and 300 Vietnamese wearing white headbands, white trousers and black tops,[6] armed with sticks, farm implements and knives,[10][23] sailed along the Arroyo Chinoise waterway and disembarked near the centre of Saigon.[10] They had pretended to be working the transport industry, delivering fruit, vegetables and building materials.[23] The plan was that this advance party would give signals to a larger party of rebels, who were waiting on the outskirts of Saigon with the majority of the weapons, to move into the city for the main part of the uprising.[23]

The advance party then attempted to proceed to the Central Prison to forcibly release Long,[10] shouting "Let's free big Brother [Long]".[23] Long had provided his followers with a detailed strategy from his prison cell, and the attack was led by a Cholon gang leader named Nguyen Van Truoc (also known as Tu Mat) with Tri's assistance.[9][10][20] Truoc was the leader of a powerful underworld gang that was linked to the Heaven and Earth Society.[20]

The French had anticipated the trouble, and police, whose presence had been increased along the waterways,[23] arrived quickly, dispersing Long's followers with ease.[21] Although some of the disciples reached the prison, none managed to breach its defenses. Ten of Long's men were killed, whereas only one sentry perished. The French arrested 65 rebels on the spot, including Tri.[10] Of these, 38 were sentenced to death.[9][23] Long was sentenced to death for his participation in the uprising, and he was executed on February 22, 1916.[24] The French Governor-General of Indochina wrote to the French Minister of Colonies, describing the incident as "a serious attempt to put in execution a vast plot that has been prepared carefully and for a long time by a secret society which grouped together with professional bandits all the enemies of our domination".[6] The colonial authorities commissioned the publication of poems, which praised French rule and warned the populace against insurrections.[23]

Similar events occurred across southern Vietnam, and in one case in Bến Tre, another self-proclaimed mystic launched an uprising that was similar to Long's 1913 effort.[25] In all, riots or uprisings broke out in 13 of the 20 provinces of Cochinchina.[23] The French declared a state of emergency and continued their crackdown against Long's followers and other rebels,[6] making a further 1,660 arrests, which resulted in 261 incarcerations.[9][23]

Aftermath and legacy

The damage inflicted on Long's organisation led many of his followers to disperse and join a group that has now developed into the Cao Đài politico-religious sect based in Tây Ninh.[9] Nevertheless, Long's uprising was significant because of its abnormal roots. It was the first uprising led by a self-styled religious leader whose support base came about due to man-made discontent.[26] Prior to Long, peasant uprisings with religious themes had always been preceded by floods, outbreaks of disease, famine, crop failure or other natural phenomena, as sections of the rural populace attributed such disasters to the wrath of the heavens and sought help from leaders who purported to have supernatural powers.[26]

Long's demise did not end the sequence of self-proclaimed mystics who raised armies and engaged in politics. During the interwar period, a sorcerer named Chem Keo claimed to be Long's reincarnation.[27] During World War II, Huỳnh Phú Sổ claimed to be a living Buddha and quickly gathered more than a million supporters. He raised a large peasant army and battled both the French and the communist Viet Minh independence movement, before being killed by the latter.[28] In another case in 1939, a Taoist attempted to demonstrate that he was immune to French bullets.[29] Furthermore, in the years immediately after World War II, the Cao Đài's numbers swelled to 1.5 million.[30]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 1.10 Smith, p. 105.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 Tai, p. 69.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Chapuis, p. 119.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 4.10 Marr, p. 222.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Chapuis, pp. 10–20.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Lam, p. 189.

- ↑ Do, p. 276.

- ↑ Marr, pp. 232–233.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 9.9 Chapuis, p. 120.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 10.8 10.9 10.10 10.11 10.12 10.13 Smith, p. 106.

- ↑ Anh, p. 238.

- ↑ Chapuis, pp. 110–120.

- ↑ Anh, pp. 239–242.

- ↑ Marr, pp. 27–31.

- ↑ Chapuis, p. 121.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 Marr, p. 223.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 Tai, p. 70.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 18.6 18.7 Tai, p. 71.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Tai, p. 187.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 20.6 20.7 Tai, p. 72.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Marr, p. 230.

- ↑ Zinoman, p. 156.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 23.6 23.7 23.8 Tai, p. 73.

- ↑ Sơn Nam (1997). Cá tính miền Nam (in Vietnamese). Nhà xuất bản trẻ. p. 90.

- ↑ Smith, p. 107.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Tai, p. 75.

- ↑ Tai, p. 79.

- ↑ Chapuis, pp. 127–132.

- ↑ Do, p. 202.

- ↑ Karnow, p. 159.

References

- Chapuis, Oscar (2000). The Last Emperors of Vietnam: from Tu Duc to Bao Dai. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-31170-6.

- Do, Thien (2003). Vietnamese Supernaturalism: Views from the Southern Region. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-30799-6.

- Karnow, Stanley (1997). Vietnam: A History. New York City: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-670-84218-4.

- Truong Buu Lam (2000). Colonialism Experienced: Vietnamese Writings on Colonialism, 1900-1931. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-06712-5.

- Marr, David G. (1970). Vietnamese Anticolonialism, 1885–1925. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-01813-3.

- Nguyen The Anh (June 2002). "From Indra to Maitreya: Buddhist Influence in Vietnamese Political Thought". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies (Singapore: Cambridge University Press) 33 (2): 225–241. doi:10.1017/s0022463402000115.

- Smith, R. B. (February 1972). "The Development of Opposition to French Rule in Southern Vietnam 1880–1940". Past & Present (Oxford University Press) 54: 94–129. doi:10.1093/past/54.1.94. ISSN 0031-2746. JSTOR 650200.

- Tai, Hue-Tam Ho (1983). Millenarianism and peasant politics in Vietnam. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press]. ISBN 0-674-57555-5.

- Zinoman, Peter (2001). The Colonial Bastille: A History of Imprisonment in Vietnam, 1862–1940. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22412-4.