Permutation matrix

The product of two permutation matrices is a permutation matrix as well.

These are the positions of the six matrices:

(They are also permutation matrices.)

In mathematics, in matrix theory, a permutation matrix is a square binary matrix that has exactly one entry 1 in each row and each column and 0s elsewhere. Each such matrix represents a specific permutation of m elements and, when used to multiply another matrix, can produce that permutation in the rows or columns of the other matrix.

Definition

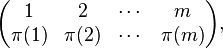

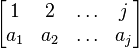

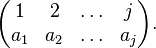

Given a permutation π of m elements,

given in two-line form by

its permutation matrix is the m × m matrix Pπ whose entries are all 0 except that in row i, the entry π(i) equals 1. We may write

where  denotes a row vector of length m with 1 in the jth position and 0 in every other position.[1]

denotes a row vector of length m with 1 in the jth position and 0 in every other position.[1]

Properties

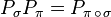

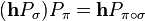

Given two permutations π and σ of m elements and the corresponding permutation matrices Pπ and Pσ

This somewhat unfortunate rule is a consequence of the definitions of multiplication of permutations (composition of bijections) and of matrices, and of the choice of using the vectors  as rows of the permutation matrix; if one had used columns instead then the product above would have been equal to

as rows of the permutation matrix; if one had used columns instead then the product above would have been equal to  with the permutations in their original order.

with the permutations in their original order.

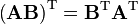

As permutation matrices are orthogonal matrices (i.e.,  ), the inverse matrix exists and can be written as

), the inverse matrix exists and can be written as

Multiplying  times a column vector g will permute the rows of the vector:

times a column vector g will permute the rows of the vector:

Now applying  after applying

after applying  gives the same result as applying

gives the same result as applying  directly, in accordance with the above multiplication rule: call

directly, in accordance with the above multiplication rule: call  , in other words

, in other words

for all i, then

Multiplying a row vector h times  will permute the columns of the vector by the inverse of

will permute the columns of the vector by the inverse of  :

:

Again it can be checked that  .

.

Notes

Let Sn denote the symmetric group, or group of permutations, on {1,2,...,n}. Since there are n! permutations, there are n! permutation matrices. By the formulas above, the n × n permutation matrices form a group under matrix multiplication with the identity matrix as the identity element.

If (1) denotes the identity permutation, then P(1) is the identity matrix.

One can view the permutation matrix of a permutation σ as the permutation σ of the columns of the identity matrix I, or as the permutation σ−1 of the rows of I.

A permutation matrix is a doubly stochastic matrix. The Birkhoff–von Neumann theorem says that every doubly stochastic real matrix is a convex combination of permutation matrices of the same order and the permutation matrices are precisely the extreme points of the set of doubly stochastic matrices. That is, the Birkhoff polytope, the set of doubly stochastic matrices, is the convex hull of the set of permutation matrices.[2]

The product PM, premultiplying a matrix M by a permutation matrix P, permutes the rows of M; row i moves to row π(i). Likewise, MP permutes the columns of M.

The map Sn → A ⊂ GL(n, Z2) is a faithful representation. Thus, |A| = n!.

The trace of a permutation matrix is the number of fixed points of the permutation. If the permutation has fixed points, so it can be written in cycle form as π = (a1)(a2)...(ak)σ where σ has no fixed points, then ea1,ea2,...,eak are eigenvectors of the permutation matrix.

From group theory we know that any permutation may be written as a product of transpositions. Therefore, any permutation matrix P factors as a product of row-interchanging elementary matrices, each having determinant −1. Thus the determinant of a permutation matrix P is just the signature of the corresponding permutation.

Examples

Permutation of rows and columns

When a permutation matrix P is multiplied with a matrix M from the left PM it will permute the rows of M (here the elements of a column vector),

when P is multiplied with M from the right MP it will permute the columns of M (here the elements of a row vector):

P * (1,2,3,4)T = (4,1,3,2)T |

(1,2,3,4) * P = (2,4,3,1) |

Permutations of rows and columns are for example reflections (see below) and cyclic permutations (see cyclic permutation matrix).

| reflections | ||

|---|---|---|

These arrangements of matrices are reflections of those directly above. |

Permutation of rows

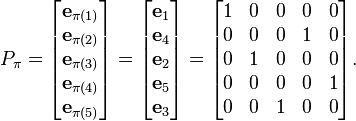

The permutation matrix Pπ corresponding to the permutation : is

is

Given a vector g,

Explanation

A permutation matrix will always be in the form

where eai represents the ith basis vector (as a row) for Rj, and where

is the permutation form of the permutation matrix.

Now, in performing matrix multiplication, one essentially forms the dot product of each row of the first matrix with each column of the second. In this instance, we will be forming the dot product of each row of this matrix with the vector of elements we want to permute. That is, for example, v= (g0,...,g5)T,

- eai·v=gai

So, the product of the permutation matrix with the vector v above, will be a vector in the form (ga1, ga2, ..., gaj), and that this then is a permutation of v since we have said that the permutation form is

So, permutation matrices do indeed permute the order of elements in vectors multiplied with them.

See also

References

- Brualdi, Richard A. (2006). Combinatorial matrix classes. Encyclopedia of Mathematics and Its Applications 108. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-86565-4. Zbl 1106.05001.