Permanent income hypothesis

The permanent income hypothesis (PIH) is an economic theory attempting to describe how agents spread consumption over their lifetimes. First developed by Milton Friedman,[1] it supposes that a person's consumption at a point in time is determined not just by their current income but also by their expected income in future years- their "permanent income". In its simplest form, the hypothesis states that changes in permanent income, rather than changes in temporary income, are what drive the changes in a consumer's consumption patterns. Its predictions of consumption smoothing, where people spread out transitory changes in income over time, departs from the traditional Keynesian emphasis on the marginal propensity to consume. It has had a profound effect on the study of consumer behavior, and provides an explanation for some of the failures of Keynesian demand management techniques.[2]

Income consists of a permanent (anticipated and planned) component and a transitory (windfall gain/unexpected) component. In the permanent income hypothesis model, the key determinant of consumption is an individual's lifetime income, not his current income. Permanent income is defined as expected long-term average income.

Assuming consumers experience diminishing marginal utility, they will want to smooth out consumption over time, e.g. take on debt as a student and also ensure savings for retirement. Coupled with the idea of average lifetime income, the consumption smoothing element of the PIH predicts that transitory changes in income will have only a small effect on consumption. Only longer lasting changes in income will have a large effect on spending.

A consumer's permanent income is determined by their assets; both physical (shares, bonds, property) and human (education and experience). These influence the consumer's ability to earn income. The consumer can then make an estimation of anticipated lifetime income. A worker saves only if they expect that their long-term average income, i.e. their permanent income, will be less than their current income.

Origins

The American economist Milton Friedman developed the permanent income hypothesis (PIH) in his 1957 book A Theory of the Consumption Function. As classical Keynesian consumption theory was unable to explain the constancy of savings rate in the face of rising real incomes in the United States, a number of new theories of consumer behavior emerged. In his book, Friedman posits a theory that encompasses many of the competing hypotheses at the time as special cases and presents statistical evidence in support of his theory.

Simple model

Consider a (potentially infinitely-lived) consumer who maximizes his expected lifetime utility from the consumption of a stream of goods  between periods

between periods  and

and  , as determined by one-period utility function

, as determined by one-period utility function  . In each period

. In each period  , he receives an income

, he receives an income  , which he can either spend on a consumption good

, which he can either spend on a consumption good  or save in the form of an asset

or save in the form of an asset  that pays a constant real interest rate

that pays a constant real interest rate  in the next period.

in the next period.

The utility of consumption in future periods is discounted at the rate  .

Finally, let

.

Finally, let ![\mathbb E_t[\cdot]](../I/m/88ed3f86f9e7af133513c97188488dab.png) denote expectation conditional on the information available in period

denote expectation conditional on the information available in period  .

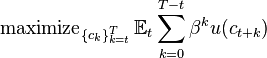

Formally, the consumer's problem is then

.

Formally, the consumer's problem is then

subject to

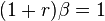

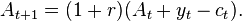

Assuming that the utility function is quadratic, and that  , the optimal consumption choice of the consumer is governed by the Euler equation

, the optimal consumption choice of the consumer is governed by the Euler equation

Given a finite time horizon of length  , we set

, we set  with the understanding the consumer spends all his wealth by the end of the last period. Solving the consumer's budget constraint forward to the last period, we determine that the consumption function is given by

with the understanding the consumer spends all his wealth by the end of the last period. Solving the consumer's budget constraint forward to the last period, we determine that the consumption function is given by

-

![c_t =\frac r{(1+r)-(1+r)^{-(T-t)}}\left[A_t + \sum_{k=0}^{T-t} \left(\frac 1 {1+r}\right)^k \mathbb E_t[y_{t+k}] \right].](../I/m/a04d0fc33c68febcd46e846432954def.png)

(1)

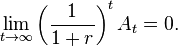

Over an infinite time horizon, we instead impose a no-Ponzi game condition, which prevents the consumer from continuously borrowing and rolling over his debt to future periods, by requiring

The resulting consumption function is then

-

![c_t =\frac r{1+r}\left[A_t + \sum_{k=0}^\infty \left(\frac 1 {1+r}\right)^k \mathbb{E}_t[y_{t+k}] \right].](../I/m/cacc1b953cee3ed6d21ff1dc5f1a8671.png)

(2)

Both expressions (1) and (2) capture the essence of the permanent income hypothesis: current income is determined by a combination of current non-human wealth  and human capital wealth

and human capital wealth  .

The fraction of total wealth consumed today further depends on the interest rate

.

The fraction of total wealth consumed today further depends on the interest rate  and the length of the time horizon over which the consumer is optimizing.

and the length of the time horizon over which the consumer is optimizing.

Empirical evidence

A seminal early test of the Permanent Income Hypothesis is Hall (1978).[3] Hall notes that if previous consumption was based on all information consumers had at the time, past income should not contain any additional explanatory power about current consumption above past consumption. This prediction is supported by the data, which Hall interprets as support for a slightly modified version of the permanent income hypothesis. Hall and Mishkin (1982)[4] analyze data from 2,000 households and find that consumption responds much more strongly to permanent than to transitory movements of income and that the PIH is compatible with 80% of households in the sample. Bernanke (1984)[5] finds "no evidence against the permanent income hypothesis" when looking at data on automobile consumption.

In contrast, Flavin (1981)[6] finds that consumption is very sensitive to transitory income shocks, a rejection of the PIH. Mankiw and Shapiro (1985)[7] however dispute these findings, arguing that Flavin's test specification (which assumes that income is stationary) is biased towards finding excess sensitivity.

More recently, Souleles (1999)[8] uses income tax refunds to test the PIH. Since a refund depends on income in the previous year, it is predictable income and should thus not alter consumption in the year of its receipt. The evidence finds that consumption does indeed respond to the income refund, with a marginal propensity to consume between 35-60%. Stephens (2003)[9] finds that the consumption patterns of social security recipients is not well explained by the PIH.

Many of the rejections of the PIH emphasize the importance of liquidity constraints. This places a focus not on the PIH's behavioral assumptions, but rather on its ancillary assumption that consumers can easily borrow or lend. This insight has led to adjustments of the simplest PIH model to account for e.g. capital market imperfections. Some of these adjustments to the PIH, such as the buffer-stock version of Carroll (1997)[10] have added further evidence supporting consumption smoothing.

Policy implications

The PIH helps explain the failure of transitory Keynesian demand management techniques to achieve its policy targets.[2] In a simple Keynesian framework the marginal propensity to consume (MPC) is assumed constant, and so temporary tax cuts can have a large stimulating effect on demand. The PIH framework suggests that a consumer will spread out the gains from a temporary tax cut over a long horizon, and so the stimulus effect will be much smaller. There is evidence supporting such a view, e.g. Shapiro and Slemrod (2003).[11]

See also

- Consumption smoothing

- Income#Meaning in economics and use in economic theory

- Milton Friedman

- Ricardian equivalence

References

- ↑ Friedman, M. (1956). "A Theory of the Consumption Function" (PDF). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Retrieved 2014-08-09.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Meghir, C. (2004). "A Retrospective on Friedman’s Theory of Permanent Income" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-08-09.

- ↑ Robert E. Hall (1978). "Stochastic Implications of the Life Cycle-Permanent Income Hypothesis: Theory and Evidence". Journal of Political Economy. 86(6). pp. 971–987.

- ↑ Robert E. Hall and Frederic S. Mishkin (1982). "The Sensitivity of Consumption to Transitory Income: Estimates from Panel Data on Households". Econometrica. 50(2). pp. 461–481.

- ↑ Ben S. Bernanke (1984). "Permanent Income, Liquidity, and Expenditure on Automobiles: Evidence From Panel Data". Quarterly Journal of Economics. 99(3). pp. 587–614.

- ↑ Majorie A. Flavin (1981). "The Adjustment of Consumption to Changing Expectations About Future Income". Journal of Political Economy. 89(5). pp. 974–1009.

- ↑ N. Gregory Mankiw and Matthew D. Shapiro (1985). "Trends, Random Walks, and Tests of the Permanent Income Hypothesis". Journal of Monetary Economics. 89(5). pp. 165–174.

- ↑ Nicholas S. Souleles (1999). "The Response of Household Consumption to Income Tax Refunds". American Economic Review. 89(4). pp. 947–958.

- ↑ Stephens, Melvin Jr. (2003). ""3rd of tha Month": Do Social Security Recipients Smooth Consumption Between Checks?". American Economic Review. 93(1). pp. 406–422.

- ↑ Christopher D. Carroll (1997). "Buffer-Stock Saving and the Life Cycle/Permanent Income Hypothesis". Quarterly Journal of Economics. 112(1). pp. 1–55.

- ↑ Shapiro, Matthew D., and Joel Slemrod (2003). "Consumer Response to Tax Rebates". American Economic Review. 93(1). pp. 381–396.

External links

- Schenk, Robert. "Permanent-Income Hypothesis".

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

![c_t = \mathbb E_t[c_{t+1}].](../I/m/e6699ee350f4c2a91862013a573b9591.png)