Peripatric speciation

| Part of a series on |

| Evolutionary biology |

|---|

Diagrammatic representation of the divergence of modern taxonomic groups from their common ancestor. |

|

Natural history

|

|

History of evolutionary theory |

|

Fields and applications

|

|

Social implications |

|

Peripatric and peripatry are terms from biogeography, referring to organisms whose ranges are closely adjacent but do not overlap, being separated where these organisms do not occur – for example on an oceanic island compared to the mainland. Such organisms are usually closely related (e.g. sister species), their distribution being the result of peripatric speciation.

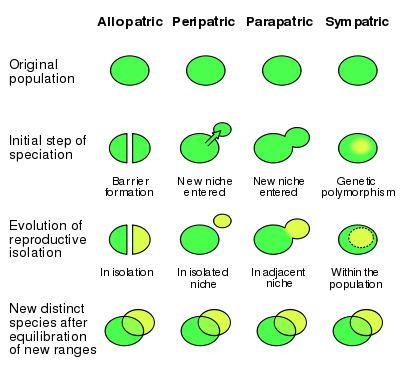

Peripatric speciation is a form of speciation, the formation of new species through evolution. In this form, new species are formed in isolated peripheral populations; this is similar to allopatric speciation in that populations are isolated and prevented from exchanging genes. However, peripatric speciation, unlike allopatric speciation, proposes that one of the populations is much smaller than the other. One possible consequence of peripatric speciation is that a geographically widespread ancestral species becomes paraphyletic, thereby becoming a paraspecies. The concept of a paraspecies is therefore a logical consequence of the Evolutionary Species Concept, by which one species give rise to a daughter species. The evolution of the polar bear from the brown bear is a well-documented example of a living species that gave rise to another living species through the evolution of a population located at the margin of the ancestral species' range.[1][2]

Peripatric speciation was originally proposed by Ernst Mayr, and is related to the founder effect, because small living populations may undergo selection bottlenecks.[3] Genetic drift is often proposed to play a significant role in peripatric speciation.[4]

References

- ↑ http://en.wikinews.org/wiki/Polar_bears_related_to_extinct_Irish_bears,_DNA_study_shows

- ↑ http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982211006452

- ↑ Provine WB (1 July 2004). "Ernst Mayr: Genetics and speciation". Genetics 167 (3): 1041–6. PMC 1470966. PMID 15280221.

- ↑ Templeton AR (1 April 1980). "The theory of speciation via the founder principle". Genetics 94 (4): 1011–38. PMC 1214177. PMID 6777243.

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||