People of the State of Texas v. Yolanda Saldívar

| People of the State of Texas v. Yolanda Saldívar | |

|---|---|

|

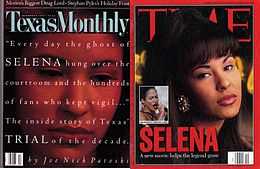

Selena on the cover of Texas Monthly and TIME. | |

| Court | Harris County Courthouse |

| Decided | October 9, 1995 –October 23, 1995 |

| Case history | |

| Subsequent action(s) | Unknown number of appeals by the defendant and two appeals by the defense team (all have since been denied) |

| Court membership | |

| Judges sitting | Mike Westergreen |

| Keywords | |

| |

The State of Texas v. Yolanda Saldívar was a criminal trial held at the Harris County Courthouse in Houston, Texas. The trial spanned from the jury's swearing-in on October 9 to opening statements on October 12, to a verdict on October 23, 1995. Former nurse Yolanda Saldívar was tried on one count of murder after the shooting death of American Tejano music singer Selena on March 31, 1995, in which she held police and the FBI Crisis Negotiation Unit at bay for almost ten hours. The case has been described as the most important trial to the Latino population and was compared to the O. J. Simpson murder trial by media outlets, as one of the most publicly followed trials in the history of the state of Texas.

On April 3, Saldívar was arraigned and pleaded not guilty; she explained that the shooting was accidental and was meant to end her own life. Judge Mike Westergren, who presided the case, appointed high-profile defense attorney Douglas Tinker and his team for Saldívar; worth an estimated $50 million. The public criticized prosecutor Carlos Valdez as an inexperienced criminal lawyer. The prosecution argued against the motion of moving venues from Corpus Christi, Texas, to Houston, while the defense believed that Selena's high-profile status in her hometown may result in an impartial jury. The prosecution team called between 45 and 50 witnesses; including Selena's father and manager of her music career Abraham Quintanilla, Jr., Selena's widower Chris Pérez, employees at Selena Etc. and at the Days Inn motel where the shooting occurred, a paramedic, several gun experts, the owners of the gun shop where Saldívar purchased the gun, emergency personnel, and Lloyd White who performed the autopsy. The defense team called fewer witnesses; including Saldívar's parents, former co-workers, motel staff at the Days Inn, Selena's former seventh grade teacher, and the lead murder investigator. The evidence used in the trial included the gun used to kill Selena, the outfit Saldívar wore the day she claimed she was sexually assaulted, and the recorded conversations between FBI negotiators Larry Young and Issac Valencia, and Saldívar.

The jury convicted Saldívar of first-degree murder after a two-hour deliberation, and was sentenced to a maximum of life imprisonment and eligibility for parole in March 2025. Fans outside the courtroom cheered, many were seen showing their excitement to the parents of Saldívar with T-shirts degrading their daughter. There were more than 200 media credentials stationed at the courthouse. The trial generated interest from Spain, Europe, South America, Australia and Japan. Tinker announced an appeal but was denied by Westergren both times in 1998 and 1999. Valdez published a book on the trial entitled, Justice for Selena: The State vs. Yolanda Saldívar in 2004. As of December 2014, Saldívar is currently representing herself and is mounting new efforts to get out of prison, citing that witnesses were not called upon and evidence went missing following the trial.

Background

Yolanda Saldívar

Saldívar, an in-home nurse for terminal cancer patients, was a fan of country music.[1][2] However, she did enjoy Shelly Lares, a Tejano music artist, and disliked Selena for dominating the categories Saldívar's favorite musician was nominated in.[3][4] In 1991, her niece persuaded her to go to a Selena concert in her hometown of San Antonio, Texas.[1] Saldívar became a fan and decided to form a fan club promoting Selena.[5] She contacted the singer's father and manager, Abraham Quintanilla, Jr. for permission to start one.[1] After a meeting with Quintanilla, Jr., Saldívar's request was accepted and became the founder and acting president of the Selena fan club.[1] In January 1994, Selena opened two boutiques in Texas, one in Corpus Christi and the other in San Antonio.[6] Because of Selena's touring schedule, she was unable to run the businesses and decided to appoint Saldívar as manager after Quintanilla, Jr. believed she was the perfect choice after a successful three year role as president of the fan club.[7]

The singer began receiving complaints from employees,[8][6] her fashion designer,[9] and her cousin about Saldívar's management skills.[9] They claimed that Saldívar mismanaged Selena's affairs, manipulated their decisions, destroyed their creations, intimidated and threatened them, and secretly recorded them without their consent or knowledge.[9] Selena didn't believe Saldívar, who became her close friend, would impose on the singer's fashion business.[10] Quintanilla, Jr. began receiving the complaints after the failed attempts to get Saldívar fired from her job. He tried convincing Selena that Saldívar may be a bad influence on her, she brushed the comments off since her father always mistrusted people.[10] In January 1995, Quintanilla, Jr. began receiving letters and phone calls from angry fans who sent their enrollment fees for the fan club and received nothing.[11] He began an investigation and found that Saldívar was embezzling $30,000 in forged checks from both the fan club and the boutiques.[12][13] On March 9, 1995, the Quintanilla family held a meeting to discuss the disappearing funds. Saldívar's answers to Quintanilla, Jr.'s questions were not convincing and he informed her that if she didn't disprove his accusations that he would get the police involved.[14][15]

Murder of Selena

The following day that Saldívar was confronted by the Quintanilla family, she was banned from contacting Selena.[14] Saldívar purchased a .38 special revolver and lied to the clerk about her intentions on purchasing the gun as a nurse whose patients relatives had threatened her life.[14] Saldívar convinced Selena to meet her alone at her Days Inn motel room on March 31, 1995.[16] At the motel room, Selena demanded financial papers necessary for tax preparation, Saldívar delayed the handover claiming she had been raped in a recent Mexico trip.[17] Selena drove Saldívar to Doctors Regional Hospital where doctors found no evidence of rape.[18] When the singer and Saldívar return to the motel room, Selena emptied Saldívar's satchel that was filled with documents regarding the boutiques and fan club as well as the .38 revolver. Saldívar grabbed the gun and pointed it at Selena.[17] As Selena attempted to flee, Saldívar shot Selena in the back, severing an artery leading from her heart.[17] Critically wounded, Selena ran to the motel's lobby and collapsed to the floor naming Saldívar as her assailant and giving the room number where she had been shot.[19][20][21] Her condition began to deteriorate rapidly as motel staff attended to her. Selena was pronounced dead at 1:05 pm from loss of blood and cardiac arrest.[22][23][24]

Arrest of Saldívar

Saldívar got into her pickup truck and attempted to leave the motel after the shooting occurred.[25] Rosario Garza, motel staff, saw Saldívar come out of her motel room with a wrapped towel.[26][27] It was believed that she was on her way to Q-Productions to shoot Quintanilla, Jr. and others waiting for Selena to arrive for a planned recording session that day.[28] However, she was spotted by a responding police cruiser. An officer emerged from the cruiser, drew his gun and ordered Saldívar to come out of the truck. Saldívar did not comply. Instead, she backed up and parked adjacent to two cars, with her truck then being blocked in by the police cruiser.[25] Saldívar then picked up the pistol, pointed it at her right temple, and threatened to commit suicide.[24] A SWAT team and the FBI Crisis Negotiation Unit were brought in.[24] Musicologist, Himilce Novas commented that the event was reminiscent of O. J. Simpson's planned suicide ten months earlier.[29]

Larry Young and Issac Valencia began negotiating with Saldívar. They ran a phone line to their base of operations (adjacent to Saldívar's pickup truck) as the standoff continued.[25] Motel guests were ordered to remain in their rooms until police escorted them out.[30] Saldívar surrendered, after nearly nine-and-a-half hours.[17] By that time, hundreds of fans had gathered at the scene; many wept as police took Saldívar away.[17][25] Within hours of Selena's murder, a press conference was called. Assistant Police Chief Ken Bung and Quintanilla, Jr., informed the press that the possible motive was that Selena went to the Days Inn motel to terminate "her" employment; Saldívar was still unidentified by name in media reports. Rudy Treviño, director of the Texas Talent Music Association and sponsor of the Tejano Music Awards, declared that March 31, 1995, would be known as "Black Friday".[31][32][33]

Trial

Pre-trial

On April 3, Saldívar was arraigned and pleaded not guilty to the murder of Selena.[34] Her bail was set at $100,000 though it was raised to $500,000 by district attorney Carlos Valdez after he considered Saldívar to be a flight risk.[35] When the bail was announced, people asked why the death penalty was not requested for Saldívar.[36] The Nueces County jail was deluged with death threats and public calls for vigilante justice. Even some gang members in Texas were reported to have taken up collections to raise the bond for Saldívar so they could kill her when she was released.[37]

Leading the murder investigation was veteran CCPD detective Paul Rivera.[38] Originally, an unnamed man was hired to defend Saldívar but withdrew from the case in fear of community retaliation and in fear of his children finding out he was in defending Saldívar who they dislike.[39] He withdrew from the case on April 4 and judge Mike Westergren began searching for a defense for her.[39] Prosecutor Carlos Valdez was designated as the lead prosecutor, while Mark Skurka was appointed as his legal counsel.[40] On April 6, a grand jury was called to determine whether to indict Saldívar of murder.[41] After about an hour, the jury had returned a true bill and the indictment was randomly assigned to the 214th District Court.[41] Carlos Valdez believed that a speedy trial with Westergren presiding the case was probable.[41]

Douglas Tinker, a 30-year veteran attorney, was assigned to Saldívar. Tinker was called one of the best criminal defenses in the state of Texas, and was estimated to be worth $50 million of representation.[42] His wife was fearful that they would suffer from community retribution, she asked Tinker not to take the case.[43] Arnold Garcia, a former district prosecutor, was chosen by Tinker as his co-counsel.[40] Tinker was given a private investigator by the judge after he requested for one.[44] His entire team spent around $20,000 to defend Saldívar.[42] The court date was originally set for August 17, but was pushed back two months for October 9 for unknown reasons.[45] On May 18, Tinker and Valdez argued about the possibility to reduce Saldívar's bond to $10,000.[46] Tinker argued that she shouldn't be in prison since she had yet been found guilty of murder and deserved to be freed. Valdez argued that if Saldívar were to be released from prison that there were no chances of them seeing her again since she had contacts in Mexico, representing a flight risk.[46] Saldívar's parents, siblings, and former co-workers argued that she had no financial resources to make bond and that she was not capable of actions she was accused for.[47] Valdez called Rivera to the stand who argued that Saldívar developed several foreign contacts as a result of working for Selena.[47] Rivera also brought into question about the ongoing investigation on the embezzlement claims, stating that Saldívar may have access to funds that the investigation have yet uncovered.[47] Westergren denied bond reduction and Saldívar was sent back to jail.[47]

After the May 18 ruling, Westergren decided to move the case to Houston, Texas. His decision was based on the demographics of Nueces County, who predominately were Hispanic people who viewed Selena as a "well known and beloved member of the Hispanic population."[48][49] On August 4, the pretrial hearings began as Tinker filed for three motions; a change of venue to Houston (which was pre-approved), the motion to suppress or exclude Saldívar's written statement, and the motion to suppress or exclude Saldívar's oral statements made at the time of her arrest.[50] Tinker presented twelve witnesses to the stand; a former district judge, former district attorney, former first assistant district attorney, several private lawyers, and members of the media.[51] They all feared that Saldívar would have an impartial jury due to the overwhelming media interest.[51] A Spanish-language radio personality informed the judge that the general consensus among Hispanics in the area was that Saldívar was guilty and that she would be acquitted because of the faulty juridical system and believed that Valdez was inexperienced.[52] The judge recessed as Valdez scrambled to find witnesses who believed the trial in Corpus Christi would be able to find an unbiased jury.[52] The parliamentary procedure resumed on August 7, as Valdez brought five witnesses who believed that despite the media interest that Saldívar could face a fair trial.[53] The following day, Westergren granted the motion to change the venue to Houston, Texas.[54]

Trial in Houston

First week of trial

The selection for jury members was completed on October 9. The jury included seven White Americans, four Hispanics, and one African American.[55] Charles Arnold, a White American former Marines juror, was likened by Tinker.[42] Westergren ordered that the entire trial would not be televised or be taped recorded and limited the number of reporters in the courtroom to avoid a "repeat of the Simpson circus".[56] The trial began on October 11, Valdez's opening statement was that Saldívar "deliberately killed Selena." calling it a "senseless and cowardly" act because Selena was shot in the back.[56][57] Valdez called the trial a "simple case of murder".[57][58] Tinker opened his statement as though as "describing a mystery movie" calling Quintanilla, Jr. a "controlling and dominating father, ambitious for power and money" and calling his actions on removing Selena from school to sing at nightclubs and bars as "the sole purpose of making money." who revoked his family's privacy by demanding they live in a compound in order to watch their every move.[57] Tinker asserted that Selena wanted to be independent and "break from her father's control" by operating her own business.[59] He believed that with the opening of her boutiques, Selena granted Saldívar as manager, who continuously received death threats from Quintanilla, Jr. for that same reason.[59] According to Tinker, after Saldívar fired the gun; she "ran after her friend to help her", by getting into her pickup truck and searching for her.[59] He claimed that Quintanilla, Jr. called Saldívar a "lesbian obsessed" with Selena.[49] Tinker ended his opening statement that Quintanilla, Jr. drove Saldívar "to near madness" by threatening to dissolve her friendship with Selena.[60]

The prosecutors first witness was Quintanilla, Jr., Valdez asked if Quintanilla, Jr. had any sexual relations or raped Saldívar, both questions were answered no from Quintanilla, Jr.[42][61] Valdez began asking him about the alleged theft, he told the court that Saldívar was thief.[61] Upon cross examination, Tinker asked Quintanilla, Jr. why he failed to provide the court with the fan club's financial records as proof since he was accusing her of misusing the funds.[61] The two began arguing back and forth and Westergren called for order.[61] Valdez called Chris Pérez, Selena's widower, who testified that he and Selena no longer trusted Saldívar long before the crime was committed.[62] Kyle Voss ad Mike McDonald from A Place to Shoot, where Saldívar purchased the gun, who said that they instructed her on the proper use of the gun.[62] They also said that she returned the gun two days later, claiming that her father gave her a pistol, she returned eleven days later repurchasing the gun.[42][62]

On October 12, Valdez appointed Trinidad Espinoza to the stand. He testified that he saw Saldívar and Selena running, with Saldívar chasing after Selena pointing the gun at her and then stopped, lowered her gun, and walked back into her motel room displaying no emotion.[63] After hearing this, Marcella Quintanilla (Selena's mother), was hospitalized with chest and arm pains due to a sudden rise in her blood pressure.[42][63] Motel maid, Norma Marie Martinez, also described the same events as Espinoza, she added that Saldívar called Selena a "bitch".[42][64] Tinker asked Martinez to point where she was on the diagram, Tinker believed Martinez could not have seen or hear anything because she was at a considerable distance from the vicinity of where the shooting occurred.[65] Emergency room personnel who attended Saldívar when Selena drove her to the hospital to be checked for rape, they noticed that Saldívar had lied to Selena about the rape as there were inconsistencies in her stories that she told them and the ones she told Selena.[66][42] Tinker asked the nurse to describe Saldívar's mood at that time, she answered that the patient showed symptoms of depression; Tinker asked her if those symptoms were consistent with those of a victim of sexual assault, the nurse agreed.[66] Another nurse who attended to Saldívar stated that she had red welts on her neck and arms, she stated that they did not resemble bruises a person may receives from a baseball bat injury, which Saldívar said had been used to assault her.[66]

The prosecutor showed the jury the outfit Saldívar had wore during her alleged rape.[21] They testified that someone purposely tore holes and shredded the shirt with scissors.[21] On October 13, Rosalinda Gonzalez, the assistant manager of the Days Inn, was called in and told the jury that when Selena arrived at the lobby after being shot, she asked the singer who shot her; Selena cried out "the girl in room 158".[21] Ruben DeLeon, motel manager, said that Selena told him "Yolanda, Yolanda Saldívar shot me. The one in room 158."[21][58] Receptionist, Shawna Vela, confessed on hearing the same statements and added that Selena screamed "lock the door!" before collapsing, Vela asked her why and the singer told her "lock the door! She'll shoot me again".[60][67] Vela told the jury that there were so much blood she felt nauseous before calling 911.[68] The last person to be called in was paramedic Richard Fredrickson who described in detail about Selena's condition and a mysterious ring she clutched in her hands.[60][69] The Quintanilla family were seen sobbing of Fredrickson's details on saving Selena's life, while Saldívar "starred blankly".[70]

Second week of trial

The trial resumed on Monday, October 16, the recorded negotiation between the FBI Crisis Negotiation Unit and Saldívar was played.[71] The tapes began as the first recorded statement of Saldívar was her stating how bad she wanted to die.[58][71] In the conversation, the jury heard Larry Young persuading her to lower the gun; Saldívar telling him that she cannot do so.[71] Young tells her that by committing suicide would only harm her parents, she then requests to contact her mother to say goodbye and ask for forgiveness.[71] She continued to wane "I just wanna die" as Young began talking about religion and if she believed in faith and perseverance from negative actions.[72] Young tells Saldívar that if she would give herself up, that he would place a jacket over her so that the media would not have a picture of her during her surrender.[73] Issac Valencia pleaded Saldívar that if she were to surrender that they promised to shut off all the lights that were pointing towards her truck, she agreed.[74] As Saldívar departed her truck, she got scared as dozens of armed policeman and FBI agents were pointing rifles and pistols at her.[74] She ran back to her truck and pointed the gun at her head, she screamed to Young "They're carrying guns! They're carrying guns! They're going to kill me! They're going to kill me!"[74] Anchor newswoman, María Celeste Arrarás, wrote in her 1997 investigative book, that she found it "curious" for a person who cried for hours that she wanted to be dead "would be afraid that someone might make her wish come true."[74] The New York Times also commented that "she alternately begged to be killed and expressed fear that she would be killed if she left the truck."[58]

As the tape conversations continued, the jury hears Saldívar's reaction to the news of Selena's death after her phone interfered from a local radio signal.[74] Saldívar's voice, now angry, asked Young why he would keep the singer's condition from her, since she wanted to visit Selena at the hospital, believing she was still alive.[75] Young tells Saldívar not to believe the radio announcement and that he doesn't know on Selena's current condition.[75] The conversation then switches to Saldívar blaming Quintanilla, Jr. for the murder expressing that he threatened to kill her.[75] She tells him how she bought the gun for protection after finding her car tires slashed purposely.[75] She also tells Young how Quintanilla, Jr. sexually abused her by "sticking a knife" in her vagina, telling Young that Quintanilla, Jr. told her that he would murder her if she went to the police.[76] When asked about what happened in her motel room, Saldívar cried: "I bought this gun to kill myself, not her, and she told me, 'Yolanda, I don't want you to kill yourself.' And we were talking about that when I took it out and pointed it to my head, and when I pointed it to my head, she opened the door. I said 'Selena, close that door,' and when I did that gun went off."[58][77]

The prosecution then told the jury that the comments by the officers planted the idea in Saldívar's head that the shooting was accidental.[77] The defense countered stating that although she did not use the word "accident", she did not mean to harm Selena.[78] John Houston, a police officer who was present during the standoff, was asked of the nine and a half hours that Saldívar placed the gun to her head, how many times did it "went off", he said "none".[79] The trial resumed on October 18, Robert Garza, a Texas Ranger, told the jury that during the preliminary hearings in Corpus Christi, he witnessed Saldívar making gestures explaining that shooting was accidental, which was left out of her confession.[58][80] The defense called Rivera to the stand and explained to the jury that Rivera had a conflict of interest after finding out that he had a poster of Selena hanging on his wall and was treated to a Selena T-shirt by Quintanilla, Jr.[81] Tinker explained to the jury that the confession was signed by Saldívar after 11 hours of exhaustion, lack of water and food, sleep deprivation, and lack of using the bathroom.[82] Tinker questioned Rivera's intentions of destroying his notes, not recording his interrogation between him and Saldívar, not providing a lawyer for her when the law requires it, and not allowing Saldívar to see her relatives after signing her confession.[82] A few days later, the Mexican mafia sent Tinker a signed postcard declaring their intentions to harm him and his family for defending Saldívar.[83]

On October 19, the defense called the two surgeons who tried to revive Selena at the hospital.[23] The defense questioned why Quintanilla, Jr. would request that a blood transfusion not to be performed on Selena due to his religious beliefs, when by law Pérez would have the say whether or not the procedure would be performed.[23] The autopsy pictures of Selena were displayed for everyone to see.[23] A White American jury member was affected by the pictures, she was seen "bursting into tears" as Lloyd White described in detail on his findings.[23][42] According to Arrarás, Saldívar was seen as "impassive" who had "lowered her head" when the autopsy pictures were shown.[23] After confirming that Selena was not pregnant, which was rumored by media reports, White announced his conclusion: "this was a homicide, not an accident."[84] The prosecution called on a firearm expert who examined the gun to be in working condition and that a person pulling the trigger must use a "great amount of pressure".[85] Valdez showed pictures of the motel room where Selena had been shot, indicating that "it was impossible for [her] not know her friend had been wounded."[85] Valdez said: "this meant that she had not come to [Selena's] aid because she chose not to."[85]

The defense arguments began on October 20 with Barbra Schultz taking the stand.[86] Tinker asked if Selena had actually screamed out to them to lock the doors, she said that Selena had never asked the doors to be locked and was only moaning on the floor.[87] Schultz further stated that her former employee, Vela, was not trustworthy.[88] Schultz also said that all the employees began formulating different opinions on what happened on March 31 when the prosecution called on them to testify.[88] Motel staff maid, Gloria Magaña, doubted the validity of Espinoza and Martinez's accounts.[88] She told the jury that it was impossible for both employees to have seen Saldívar chasing after Selena because their line of duty was on the other side of the motel building.[88] Magaña claimed to have seen Selena running through the parking lot, but did not see Saldívar chasing after her.[88] Tinker called Marilyn Greer, Selena's seventh grade teacher, to the stand.[89] She told the jury that Selena had the ability to graduate with honors who easily could obtain a college scholarship.[89] Greer then spoke about how Quintanilla, Jr. stripped those possibilities for Selena away by wasting her youth by forcing her to sing at nightclubs and bars for money, unhealthy for a thirteen-year-old girl.[89]

Third week of trial

On October 23, the defense argued their closing arguments.[90] The defense argued that the shooting was an accident and that Rivera was "not interested in pursing justice. He wanted to make a case."[90] The defense also argued that Rivera knew hours beforehand that the Saldívar case was "a big case" and had "wanted to be the one to get [her]."[90] They also argued that Selena still refereed to Saldívar as her "dearest friend" citing that the singer took her to the hospital, despite having a recording session scheduled that day.[90] The defense used one of the employee's demonstration that the gun can "fire off" with "just one's little finger."[90] The defense accused the prosecution of manipulating the jury's emotions by displaying photographs of Selena at the morgue and the trial of blood that was traced from the motel room to the lobby.[90] They concluded by telling the jury to not side with a "rabid father".[90]

The prosecution's closing statement had Skurka telling the jury that Selena "had been reduced to a mere picture thanks to the March 31 actions of the defendant."[91] Skurka asked the jury why Saldívar (a nurse) did not administer first aid and why had she not called 911 after accidentally shooting the singer in the back.[92][93] Skurka then provided details on the three different stories given by Saldívar on the reason on purchasing a gun, as well as giving different stories about her alleged rape.[94] The prosecutor pointed out that if Saldívar had wanted to commit suicide she had ample time to do so.[94] Valdez took out a calender for the month of March 1995 and chronologically pointed out the events proceeding the killing of Selena.[95] According to Valdez, Saldívar hated Quintanilla, Jr. and believed that she got revenge by killing his daughter "someone he loved the most."[95]

Verdict and reactions

Saldívar's crime was punishable to up to 99 years in prison and a $10,000 fine.[96] Saldívar was kept at Nueces County jail under a suicide watch before her trial.[97] After the closing arguments, the jury deliberated for two hours and twenty-three minutes.[98] As people were waiting for the verdict, prosecutors and the defense team signed autographs for the media; as well as Saldívar.[42] Saldívar's family also signed autographs, while Quintanilla, Jr. remained in his seat awaiting the jury.[42] The jury found Saldívar guilty of first-degree murder.[92] She received the maximum sentence of life in prison with parole eligibility in 30 years.[92]

Before the verdict was read, crowds and Quintanilla, Jr. were skeptical of the outcome of the trial after O. J. Simpson's acquittal trial a week earlier.[49] Saldívar told her defense team that she wanted to kill herself after the verdict was read.[42] The Hispanic population cheered as Westergren delivered the verdict and the sentencing of Saldívar.[92][99] Celebrations and festivals were planned throughout the states of Texas and California and in some areas in Mexico. Fans outside the courtroom began playing Selena's music and cheered for hours, some fans were seen cheering in Saldívar's face as police officers drove her off to prison.[99] Other fans prayed and cried out that justice had been served for them.[99] Traffic in Texas were reportedly standstill as people took to the streets and highways in festive cheering.[99] Saldívar's parents were met with negative fans who showed T-shirts degrading Saldívar's name and screams from fans who told them "now let's kill the murderer!" and "hang the witch".[42][99] The verdict was front-page news in dozens of newspapers across the United States.[100]

Media coverage and aftermath

The Spanish-language media refereed this case as the "O. J. Simpson trial for Hispanics."[101] The trial was often compared to the O. J. Simpson trial in the media.[42] It was the most watched-for trial in years in the state of Texas.[42] The Brownsville Herald called the case "the biggest courthouse media event to hit Houston."[102] In a 68-page letter by Univision and a three-page by Court TV petition Westergren to allow them to record the entire trial, who later denied all requests.[42][102][103] According to Texas Monthly, there were more than 200 media credentials stationed at the courthouse.[42] Univision and Telemundo aired approximately 90 minutes worth of coverage daily.[42] Arrarás was called "the trial's undisputed media star" for her coverage of the trial and her Primer Impacto program had the "most knowledgeable courtroom analyst" with former state district judge Jorge Rangel, who provided his expertise on the law to those unfamiliar with its terminology.[42] During the playing of the recorded conversations between Saldívar and Young in the courtroom, Saldívar called out "Where's Larry?"; a mantra that was sold as T-shirts to crowds.[42] The Chicago Tribune noticed how the divide in interest to the Selena murder trial was among Hispanics and White Americans. Donna Dickerson, a White American magazine publisher, told the Chicago Tribune that she had no interest in the trial because of Selena's "Hispanic background" and argued that Mexican Americans did not show the same enthusiasm when Elvis Presley was found dead.[56] The Selena murder trial was called the "trial of the century" and the most important trial to the Hispanic population.[104][105][106][107] The trial generated interest from Spain, Europe, South America, Australia and Japan.[108][109]

Tinker announced an appeal before signing autographs from cheering crowds.[42] The following week, Westergren denied the request and "called the prosecutors' action "somewhat problematic," but decided an appeals court should decide on a retrial."[110] Both requests for an appeal were denied on 3 October 1998 and on 19 August 1999.[110] On 22 November 1995, she arrived at the Gatesville Unit (now the Christina Crain Unit) in Gatesville, Texas, for processing.[111] Saldívar is currently serving her sentence at Mountain View Unit in Gatesville, operated by the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. She will be eligible for parole on March 30, 2025.[112] Because of multiple internal death threats from incarcerated Selena fans, Saldívar was placed in isolation and spends 23 of every 24 hours alone in her 9 by 6 feet (2.7 by 1.8 m) cell, apart from other inmates who may want to do her harm.[113] Saldívar has asked the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals to accept a petition that challenges her conviction. She claims the petition was filed in 2000 with the 214th District Court, but was never sent to the higher court. Her request was received on March 31, 2008, the thirteenth anniversary of Selena's death.[114]

Tinker and Garcia told the Texas Monthly magazine editor that by losing the trial it lessen their chances of getting shot.[42] Hispanics in Texas had a reassurance in the state's juridical system after the verdict was read.[42] The League of United Latin American Citizens began a campaign that would encouraged Hispanics to seek jury duty.[42] E! aired the trial as part of an episode of E! True Hollywood Story in December 1996, with People magazine calling it "too cheap-looking to have any dramatic impact." but found the characters playing Tinker "interesting".[115] Under a judge's order, the gun used to kill Selena was destroyed in 2002, and the pieces thrown into Corpus Christi Bay.[116][117] However, fans and historians disapproved of the decision to destroy the gun citing that the event was historical and the gun should have been in a museum.[118] In 1997, Arrarás published her book Selena's Secret, which included interviews with Saldívar and her list of claims of the singer's "real life" and her side of what happened on March 31. The book was met with negative reviews from fans as well as Quintanilla, Jr. who claimed Arrarás sympathized with a person who was convicted of murder.[119] Valdez published his book on the trial, Justice for Selena: The State vs. Yolanda Saldivar in 2004.[109] The following year, he talked to 200 students majoring in political science at Texas A&M University about his publication.[109]

In December 2014, the San Antonio Express-News, reported that Saldívar was "mounting a new legal effort to get an early release from prison, following numerous appeals in her case."[120] The news of Saldívar's potential early release was spawned by a fake news agency who reported that Saldívar would be released as early as January 1, 2015.[120] The information sparked a social media frenzy among fans.[120] Valdez told the San Antonio Express-News that Saldívar is currently representing herself and that a court date has yet been made.[120] Quintanilla, Jr. said that he "doesn't care" if Saldívar got an early release, citing that "nothing is going to bring my daughter back." though saying that Saldívar would be safer in prison rather than being freed.[120] Saldívar claims that witnesses were not called on and files have gone missing since the end of the trial.[120]

See also

- O. J. Simpson murder case

- History of the United States (1991–present)

- History of Texas

- Historical events of Houston

- 1995 in the United States

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Arrarás 1997, p. 72.

- ↑ Patoski 1996, p. 110.

- ↑ Patoski 1996, p. 111.

- ↑ Richmond 1995, p. 78.

- ↑ Arrarás 1997, p. 73.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Arrarás 1997, p. 78.

- ↑ Arrarás 1997, p. 77.

- ↑ Patoski 1996, p. 169.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Patoski 1996, p. 170.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Patoski 1996, p. 182.

- ↑ Arrarás 1997, p. 84.

- ↑ Arrarás 1997, pp. 228-229.

- ↑ Liebrum, Jennifer; Jaimeson, Wendell (27 October 1995). "Selena's Killer Gets 30 Years". New York Daily News. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Patoski 1996, p. 183.

- ↑ Arrarás 1997, p. 85.

- ↑ Patoski 1996, p. 159.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 Sam Howe Verhovek (April 1, 1995). "Grammy Winning Singer Selena Killed in Shooting at Texas Motel". The New York Times. p. 1. Retrieved October 24, 2011.

- ↑ "12 October 1995 testimony of Carla Anthony". Houston Chronicle, October 12, 1995. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ↑ Patoski 1996, p. 161.

- ↑ "Friday, 13 October, testimony of Shawna Vela". Houston Chronicle, October 13, 1995. Retrieved February 1, 2008.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 Arrarás 1997, p. 132.

- ↑ Villafranca, Armando and Reinert, Patty. "Singer Selena shot to death". Houston Chronicle, April 1, 1995. Retrieved February 1, 2008.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 Arrarás 1997, p. 155.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Patoski 1996, p. 162.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 "Famous Crime Scene". Season 1. March 12, 2010. 30 minutes in. VH1. More than one of

|season=and|seriesno=specified (help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ Arrarás 1997, p. 37.

- ↑ Novas 1995, p. 8.

- ↑ Arrarás 1997, p. 235.

- ↑ Novas 1995, p. 10.

- ↑ Novas 1995, p. 12.

- ↑ Patoski 1996, p. 200.

- ↑ Anne Pressley, Sue (1 April 1995). "Singer Selena Shot to Death in Texas". The Washington Post. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ↑ Corcoran, Michael (3 April 2005). "Dreaming of Selena". Austin American-Statesman. Retrieved 14 November 2011. (subscription required)

- ↑ Williams, Frank B; Lopetegui, Enrique (3 April 1995). "Mourning Selena : Nearly 4,000 Gather at L.A. Sports Arena Memorial for Slain Singer". Latin Times. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ↑ Valdez 2004, p. 14.

- ↑ Arrarás 1997, pp. 43-44.

- ↑ Patoski 1996, p. 203.

- ↑ Valdez 2004, p. 16.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Valdez 2004, p. 17.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Arrarás 1997, p. 43.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 Valdez 2004, p. 20.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 42.4 42.5 42.6 42.7 42.8 42.9 42.10 42.11 42.12 42.13 42.14 42.15 42.16 42.17 42.18 42.19 42.20 42.21 42.22 42.23 Patoski, Joe Nick (December 1995). "The Sweet Song of Justice". Texas Monthly. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ↑ Arrarás 1997, p. 42.

- ↑ Valdez 2004, p. 26.

- ↑ Valdez 2004, p. 21.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Valdez 2004, p. 23.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 47.3 Valdez 2004, p. 24.

- ↑ Valdez 2004, pp. 24-25.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 "Once Seemingly Open-and-shut, Selena Murder Trial Is Complex". Sun Sentinel. 8 October 1995. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ↑ Valdez 2004, p. 35.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Valdez 2004, p. 37.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Valdez 2004, p. 38.

- ↑ Valdez 2004, p. 39.

- ↑ Valdez 2004, p. 42.

- ↑ Arrarás 1997, p. 120.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 de la Gaza, Paul (12 October 1995). "Trial In Selena's Killing Exposes Cultural Divide". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 Arrarás 1997, p. 125.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 58.2 58.3 58.4 58.5 "Star's Death: An Accident Or a Murder?". The New York Times. 22 October 1995. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 59.2 Arrarás 1997, p. 126.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 "Selena Named Suspect as Killer, Witness Testifies : Courts: Motel clerk says singer screamed, 'Lock the door! She'll shoot me again!' and named 'Yolanda . . . ' in the chaos after gunfire.". Los Angeles Times. 14 October 1995. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 61.2 61.3 Arrarás 1997, p. 127.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 Arrarás 1997, p. 128.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Arrarás 1997, p. 129.

- ↑ Arrarás 1997, pp. 129-130.

- ↑ Arrarás 1997, p. 130.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 66.2 Arrarás 1997, p. 131.

- ↑ Arrarás 1997, pp. 132-133.

- ↑ Arrarás 1997, p. 133.

- ↑ Arrarás 1997, p. 134.

- ↑ Schwartz, Mike; Jaimeson, Wendell (14 October 1995). "Selena's Last Cries Shot Singer Begged Help, Named Suspect". New York Daily News. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 71.2 71.3 Arrarás 1997, p. 137.

- ↑ Arrarás 1997, pp. 138-139.

- ↑ Arrarás 1997, p. 139.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 74.3 74.4 Arrarás 1997, p. 140.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 75.2 75.3 Arrarás 1997, p. 141.

- ↑ Arrarás 1997, p. 142.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Arrarás 1997, p. 144.

- ↑ Arrarás 1997, pp. 144-145.

- ↑ Arrarás 1997, p. 146.

- ↑ Arrarás 1997, p. 149.

- ↑ Arrarás 1997, p. 150.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 Arrarás 1997, p. 151.

- ↑ Arrarás 1997, p. 152.

- ↑ Arrarás 1997, pp. 155-156.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 85.2 Arrarás 1997, p. 156.

- ↑ Arrarás 1997, p. 157.

- ↑ Arrarás 1997, pp. 157-158.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 88.2 88.3 88.4 Arrarás 1997, p. 158.

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 89.2 Arrarás 1997, p. 159.

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 90.2 90.3 90.4 90.5 90.6 Arrarás 1997, p. 166.

- ↑ Arrarás 1997, p. 167.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 92.2 92.3 "Yolanda Saldivar found guilty of Selena's murder". CNN. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ↑ Arrarás 1997, pp. 167-168.

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 Arrarás 1997, p. 168.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 Arrarás 1997, p. 169.

- ↑ "Fan club president admits shooting of Tejano singer Selena, police say". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. April 4, 1995. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- ↑ Ross E. Milloy (April 3, 1995). "For Slain Singer's Father, Memories and Questions". The New York Times. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- ↑ Arrarás 1997, p. 170.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 99.2 99.3 99.4 Arrarás 1997, p. 171.

- ↑ Arrarás 1997, p. 174.

- ↑ Ruddy, Jim. "Selena Murder Trial: Interview With Maria Celeste Arrarás". Texas Archives.org. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 Graczyk, Michael (8 September 1995). "Sept/8 Media hoopla expected for Selena murder trial". The Brownsville Herald. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ↑ "Judge Bars Live Tv Coverage Of Selena Murder Trial". The Victoria Advocate. 6 September 1995. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ↑ Anijar, Karen. "Selena-Prophet, Profit, Princess" (PDF). VWC.edu. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ↑ Mazur 2001, p. 83.

- ↑ Legon, Jeordan (16 October 1995). "Selena trial becomes obsession to Latinos". Sun Journal (James R. Costello Sr.). Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ↑ "Latinos Eagerly Await Trial Of Selena's Accused Killer". Orlando Sentinel. 16 October 1995. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ↑ Colloff, Pamela (April 2010). "Dreaming of Her". Texas Monthly. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ↑ 109.0 109.1 109.2 Saugier, Mari (2 December 2005). "Valdez recounts Selena tragedy". Corpus Christi Caller-Times. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ↑ 110.0 110.1 "News of singer Selena's death hit fans hard". Houston Chronicle. 26 August 2001. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ↑ Bennett, David. "Somber Saldívar delivered to prison – Convicted murderer of Tejano star Selena keeps head down during processing." San Antonio Express-News. November 23, 1995. Retrieved September 26, 2010.

- ↑ "Offender Information Detail Saldívar, Yolanda." Texas Department of Criminal Justice. October 26, 1995. Retrieved December 30, 2010. Enter the SID "05422564."

- ↑ Graczyk, Michael (October 28, 1995). "A grim, isolated life in prison seems likely for Selena's killer". The Dallas Morning News. Retrieved November 14, 2011.(subscription required)

- ↑ Cavazos, Mary Ann (1 April 2008). "Selena's Killer Asks Court to Review Writ". Corpus Christi Caller-Times (Corpus Christi, Texas). Retrieved 6 April 2008.

- ↑ Gliatto, Tom (23 December 1996). "Picks and Pans Review: The Selena Murder Trial: the E! True Hollywood Story". People 46 (26). Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ↑ National Briefing Southwest: Texas: Gun That Killed Singer Is To Be Destroyed The New York Times, June 8, 2002. Retrieved on July 16, 2006.

- ↑ Compiled, Items (June 11, 2002). "Gun used in slaying of Selena destroyed". chicagotribune.com (Chicago Tribune). Retrieved October 26, 2011.

- ↑ Orozco, Cynthia. "Quintanilla, Selena". Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ↑ Carrion, Kelly (3 March 2015). "'Selena's Secret,' Maria Celeste Arrarás Talks Of Book's New Edition". NBC News. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ↑ 120.0 120.1 120.2 120.3 120.4 120.5 White, Tyler (10 December 2014). "Selena’s killer Yolanda Saldivar really is mounting new legal effort for early release". San Antonio Express-News. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

Sources

- Patoski, Joe Nick (1996). Selena: Como La Flor. Boston: Little Brown and Company. ISBN 0-316-69378-2.

- Arrarás, María Celeste (1997). Selena's Secret: The Revealing Story Behind Her Tragic Death. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0684831937.

- Valdez, Carlos (2004). Justice for Selena -The State Versus Yolanda Saldivar. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 1412065259.

- Novas, Himilce (1995). Remembering Selena. Turtleback Books. ISBN 0613926374.

- Mazur, Eric Michael (2001). God in the Details: American Religion in Popular Culture. Psychology Press. ISBN 0415925649.

- Richmond, Clint (1995). Selena!: The Phenomenal Life and Tragic Death of the Tejano Music Queen. Pocket Books. ISBN 0671545221.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||