Penmanshiel Tunnel

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Location | Scottish Borders |

| Coordinates | 55°53′47″N 2°19′40″W / 55.896301°N 2.327864°WCoordinates: 55°53′47″N 2°19′40″W / 55.896301°N 2.327864°W |

| Status | Disused (abandoned) |

| Operation | |

| Opened | 1846 |

| Owner |

North British Railway London & North Eastern Railway British Rail |

| Technical | |

| Line length | 244 metres |

| No. of tracks | 2 |

| Track gauge | Standard Gauge |

| Electrified | No |

| Operating speed | 50 miles per hour |

Penmanshiel Tunnel is a now-disused railway tunnel near Grantshouse, Berwickshire, in the Scottish Borders region of Scotland. It was formerly part of the East Coast Main Line between Berwick-upon-Tweed and Dunbar.

The tunnel was constructed during 1845-46 by the contractors Ross and Mitchell, to a design by John Miller, who was the Engineer to the North British Railway.[1] Upon completion, the tunnel was inspected by the Inspector-General of Railways, Major-General Charles Pasley, on behalf of the Board of Trade.[1]

The tunnel consisted of a single bore, 244 metres long, containing two running lines.

During its 134-year existence, the tunnel was the location for two incidents investigated by HM Railway Inspectorate. The first was in 1949, when a serious fire destroyed two carriages of a south-bound express from Edinburgh. Seven passengers were injured, but there were no fatalities.[2]

The second incident occurred on 17 March 1979 when, during improvement works, a length of the tunnel collapsed. Two workmen were killed, and 13 others managed to escape. Later it was determined that the ground was not stable enough to excavate and rebuild the tunnel, so it was sealed up and a new alignment was made for the railway, in a cutting to the west of the hill.

The tunnel was also affected by the August 1948 floods. The damage caused by these floods led to the abandonment of much of the railway network in the south east of Scotland.[3]

August 1948 floods

On 12 August 1948, 6.25 inches (160 mm) of rain fell in the area; the total for the week being 10.5 inches (265 mm).[3] Rain falling on the Lammermuir Hills surged into the Eye Water towards Reston, and the channel could not accommodate all of the water. The flood water then backed up the tunnel and flowed to sea in the opposite direction, towards Cockburnspath. The tunnel was flooded to within two feet of the crown of the portal.[4]

Train fire (1949)

On the evening of 23 June 1949 a fire broke out in the tenth coach of an express passenger train from Edinburgh to King's Cross, about two and a half miles beyond Cockburnspath. The train stopped somewhere near the tunnel, within one and a quarter minutes of the fire starting, but the fire spread rapidly and with such ferocity that, within seconds, the brake-composite carriage was engulfed and the fire had spread to the coach in front. Most passengers escaped by running to the guard's compartment or forwards along the corridor, but some were compelled to break the windows and jump down onto the track. One lady was seriously injured by doing this.[5]

The train crew reacted quickly to the incident. The four coaches behind the two ablaze were uncoupled and pushed back, leaving them isolated up the line. Having drawn forward and uncoupled the two burning vehicles, the driver proceeded with the front eight coaches to Grantshouse station.[5]

The cause of the fire was thought to be a cigarette end or lighted match dropped against a partition in the corridor. This did not explain the reason for its rapid spread.[5]

Despite the severity of the blaze, which reduced the two carriages to their underframes, only seven passengers were injured, with no fatalities.[2]

Tunnel collapse (1979)

The next significant event to occur at the tunnel was the last, as it led to its abandonment.

Upgrading work

Work was being carried out to increase the internal dimension of the tunnel to allow 8 ft 6 in (2.59 m) high containers to travel through it on freightliner wagons. This was done by lowering the track, in a process involving removing the existing track and ballast, digging out the floor of the tunnel and then laying new track set on a concrete base.[1]

As the tunnel was on a very busy main line, and in order to minimise the disruption to passenger and freight services, it was decided that each of the two tracks through the tunnel would be renewed separately, with trains continuing to run on the adjacent open track.

Work was completed on the "Up" (southbound) track by 10 March 1979, and trains were then transferred to this track by the following day, to allow the "Down" (northbound) track to be modified.[1]

Tunnel collapse

At the time the tunnel collapsed there were a total of 15 people and 5 items of plant inside. According to the Railway Inspectorate report, shortly before 3:45am the duty Railway Works Inspector noticed some small pieces of rock flaking away from the tunnel wall, approximately 90 metres from the southern portal. He decided that it would be wise to shore up the affected piece of the tunnel and was making his way towards the site office to arrange this when he heard the sound of the tunnel collapsing behind him.[1]

It is estimated that approximately 20 metres of the tunnel arch collapsed, with the resultant rock fall filling 30 metres of the tunnel from floor to roof, totally enveloping a dumper truck and a JCB. Thirteen of the people inside the tunnel at the time of the collapse escaped successfully; the dumper truck and JCB operators could not be accounted for, and were killed in the accident.

Official report

An official HM Railway Inspectorate report[1] was written by Lieutenant Colonel I.K.A. McNaughton, on 2 August 1983. The report concluded that it was impossible to be certain as to the cause of the collapse as access could not be gained to the collapsed portion of the tunnel.

The report suggested that the collapse was likely to be the result of over-stressing of the natural rock on which the brick arch rings were founded. It was likely to have happened at some time in any event and there was insufficient evidence to say whether or not it had been triggered by the excavation.

Finally the report stated that there were no grounds for finding any individual responsible for the accident. British Rail was charged in the High Court, in Edinburgh, with health and safety offences. It was found guilty and fined £10,000.

Replacement works

After the collapse, it was originally the intention of British Rail to re-open the tunnel by removing the collapsed material and repairing the structure of the tunnel. Once the extent of the collapse became apparent, it was decided that this operation would be too difficult and dangerous, and that a more expedient and cost effective option would be to construct a new alignment for the railway.[1]

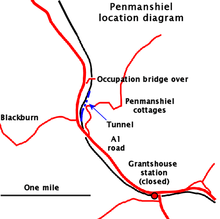

This decision resulted in around one kilometre (1,100 yards) of existing railway (including the tunnel itself) being abandoned and replaced by a new section of line constructed in open cut, somewhat to the west of the original course.[6] The operation to reopen the railway took five months of round-the-clock working.[6] The portals of the collapsed tunnel were sealed to prevent unauthorised access.

The contractor Sir Robert McAlpine & Sons Ltd started work on the new alignment on 7 May 1979, and it was completed on 20 August.[1][7]

During the closure, some trains from King's Cross terminated at Berwick, with onward services being provided by a fleet of buses, some towing trailers for luggage. The bus service went as far as Dunbar, where a railway shuttle took over between Dunbar and Edinburgh. Other East Coast Mainline Intercity 125 services to Edinburgh were diverted via Newcastle, Carlisle and Carstairs.[7]

Road diversion

As a result of the work to re-align the railway line, it was also necessary to alter the course of the A1 trunk road. A map of the area, showing both the railway and the road diverting to the west is available.[8]

Visible remains

.jpg)

Since the tunnel was closed, the landscape has gradually 'returned to nature'. The southern portal has been covered by the hillside, and the only clues to the route of the old line are a dry-stone wall marking the railway boundary, and a disused bridge that used to carry the A1 main road over the line.

Memorial

As the collapsed portion of the tunnel was never excavated, the site became the final resting place of Gordon Turnbull from Gordon 22 miles away and Peter Fowler from Eyemouth, who were killed when the tunnel collapsed. A three-sided obelisk was erected over the point where the tunnel collapsed to act as a memorial. One face of the obelisk displays a cross, while each of the other two faces commemorates one of the men killed.[1]

The memorial is adjacent to a road running over the hill and is marked on 1:50,000 and 1:25,000 scale OS maps, at grid ref: NT 797670 . From the maps it is also possible to determine the abandoned section of the A1 road, but the original course of the railway is not visible.

Gallery

-

..jpg)

'Merry-go-round' (MGR) coal train heading north on the new alignment.

-

.jpg)

The diverted A1, and the new railway cutting

-

.jpg)

Memorial to Peter Fowler

(click for inscription) -

..jpg)

Memorial to Gordon Turnbull

(click for inscription)

See also

- Railway accidents in Scotland

- London and North Eastern Railway – operated the rail services between 1923 and 1948

- British Rail – operated the rail services between 1948 and abandonment of the tunnel

- Penmanshiel

- List of places in the Scottish Borders

- List of places in Scotland

References

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Report on the Collapse of Penmanshiel Tunnel that occurred on 17th March 1979 by Lt. Col. I.K.A. McNaughton, 2 August 1983, Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, England.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Col. R. J. Walker (1952). "Report on the Fire which occurred in an Express Passenger Train on 14th July 1951 near Huntingdon in the Eastern Region British Railways" (PDF). Ministry of Transport / HMSO. Retrieved 2007-07-12.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Thomas (1971)

- ↑ Nock and Cross (1982) pp 87 - 88.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Rolt (1966), pp 264-268

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Biddle, Gordon (1990). The Railway Surveyors. London: Ian Allan Ltd. and British Rail Property Board. ISBN 0-7110-1954-1.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Nock and Cross (1982) pp 192 - 193.

- ↑ http://maps.google.co.uk/maps?ie=UTF8&oe=UTF-8&hl=en&q=&ll=55.88417,-2.305584&spn=0.044481,0.159645&z=13&iwloc=addr&om=1

Sources

- Nock, O. S.; Cross, Derek (1960). Main Lines Across the Border (1st edition ed.). London: Nelson. OCLC 12273673.

- Nock, O. S.; Cross, Derek (1982). Main Lines Across the Border (Revised edition ed.). Shepperton: Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-1118-4. OCLC 11622324.

- Rolt, L. T. C. (1966). Red for Danger (2nd ed.). Newton Abbot, Devon: David & Charles. OCLC 897379.

- Thomas, John (1971). A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain. VI Scotland: The Lowlands and the Borders (1st ed.). Newton Abbot, Devon: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-5408-6. OCLC 16198685.

- Thomas, John; Paterson, Rev A. J. S. (1984). A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain. VI Scotland: The Lowlands and the Borders (2nd ed.). Newton Abbott, Devon: David & Charles. ISBN 0-9465-3712-7. OCLC 12521072.

Further reading

- Report on the Accident which occurred on 23 June 1949 at Penmanshiel in the Scottish Region British Railways (HMSO, 1949)

External links

- Report on the Collapse of Penmanshiel Tunnel at The Railways Archive.(C) Crown Copyright acknowledged)

- Report on the Fire which occurred in an Express Passenger Train on 23rd June, 1949, at Penmanshiel Tunnel in the Scottish Region British Railways at The Railways Archive.(C) Crown Copyright acknowledged)

- Report on the Fire which occurred in an Express Passenger Train on 14th July 1951 near Huntingdon in the Eastern Region British Railways at The Railways Archive.(C) Crown Copyright acknowledged)

- (HMSO, 1952) – This fire shared many similarities with the Penmanshiel fire of 1949, and the report makes frequent references to it. Section 27 and later are particularly relevant.

Photographic resources

- Pre-collapse: "A4 60004 "William Whitelaw" emerging from Penmanshiel Tunnel :– clearly shows relationship between railway, tunnel and road bridge, at southern portal.". 22 June 1959. Retrieved 17 May 2013.