Pawnee mythology

Pawnee mythology is the body of oral history, cosmology, and myths of the Pawnee concerning their gods and heroes. The Pawnee are a federally recognized tribe of Native Americans, originally located on the Great Plains along tributaries of the Missouri River and currently in Oklahoma. They traditionally speak Pawnee, a Caddoan language.

Deities

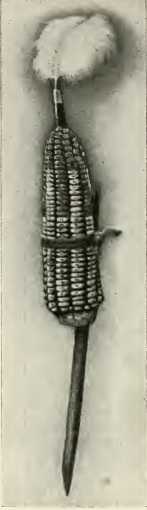

Atius Tirawa, which means "Father Above" in the Pawnee language,[1] was the Creator god[lower-alpha 1] He was believed to have taught the Pawnee people tattooing, fire-building, hunting, agriculture, speech and clothing, religious rituals (including the use of tobacco and sacred bundles), and sacrifices. He was associated with most natural phenomena, including stars and planets, wind, lightning, rain, and thunder. The wife of Tirawa was Atira, goddess of the Earth. Atira was associated with corn.[2]

The solar and lunar deities were Shakuru and Pah, respectively. Four major stars were said to represent gods and were part of the Creation myth, in which the first human being was a girl. The Morning Star and Evening Star mated to create her.

Beliefs and Practices

Archeologists and anthropologists have determined the Pawnee had a sophisticated understanding of the movement of stars. They noted the nonconforming movements of both Venus (Evening Star) and Mars (Morning Star). The Pawnee centered all aspects of daily life on this celestial observation, including the important cultivation cycle for sacred corn.

They built earthwork lodges to accommodate the sedentary nature of Pawnee culture; each lodge "was at the same time the universe and also the womb of a woman, and the household activities represented her reproductive powers."[3] The lodge also represented the universe in a more practical way. The physical construction of the house required setting up four posts to represent the four cardinal directions, “aligned almost exactly with the north-south, east-west axis.[4]

Along with the presence of the posts, four other requirements marked the Pawnee lodge as an observatory:

- "A Pawnee observatory-lodge would have an unobstructed view of the eastern sky”;

- "A lodge’s axis would be oriented east-west so that at the vernal equinox the sun’s first light would strike the altar”;

- “The size parameters of the lodge’s smoke hole and door (height and width) would be designed to view the sky”; and

- “An observatory-lodge’s smoke hole would be constructed to view certain parts of the heavens - such as the Pleiades.” [5]

Through both the historical and archaeological record, it is clear that the Pawnee lifestyle was centered on the observation of the celestial bodies, whose movements formed the basis of their seasonal rituals. The positions and construction of their lodges placed their daily life in the center of a scaled-down universe. They could observe the greater universe outside and be reminded of their role in perpetuating the universe.

According to one Skidi band Pawnee man at the beginning of the twentieth century, “The Skidi were organized by the stars; these powers above made them into families and villages, and taught them how to live and how to perform their ceremonies. The shrines of the four leading villages were given by the four leading stars and represent those stars which guide and rule the people.”[6]

The Pawnee paid close attention to the universe and believed that for the universe to continue functioning, they had to perform regular ceremonies. These ceremonies were performed before major events, such as semi-annual buffalo hunts, as well as before many other important activities of the year, such as sowing seeds in the spring and harvesting in the fall. The most important ceremony of the Pawnee culture, the Spring Awakening ceremony, was meant to awaken the earth and ready it for planting. It can be tied directly to the tracking of celestial bodies.

“The position of the stars was an important guide to the time when this ceremony should be held. The earth-lodge served as an astronomical observatory and as the priests sat inside at the west, they could observe the stars in certain positions through the smokehole and through the long east-oriented entranceway. They also kept careful watch of the horizon right after sunset and just before dawn to note the order and position of the stars.” [7] The ceremony must be held at exactly the right time of year, when the priest first tracked “two small twinkling stars known as the Swimming Ducks in the northeastern horizon near the Milky Way.”[8]

Nahurac

In the Pawnee traditional religion, the supreme being Tirawa conferred miraculous powers on certain animals. These spirit animals, the nahurac, act as Tirawa's messengers and servants, and can intercede with him on behalf of the Pawnee. The nahurac had five dwellings, and were miraculous.[9]

The nahurac had five lodges. The foremost among them was Pahuk, usually translated "hill island", a bluff on the south side of the Platte River, near the town of Cedar Bluffs in present-day Saunders County, Nebraska.[10]

Lalawakohtito, or "dark island", was an island in the Platte near Central City, Nebraska.

Ahkawitakol, or "white bank", was on the Loup River opposite the mouth of the Cedar River in what is now Nance County, Nebraska.

Kitzawitzuk, translated "water on a bank", also known to the Pawnee as Pahowa, was a spring on the Solomon River[9]:358 near Glen Elder, Kansas. It now lies beneath the waters of Waconda Reservoir.[11]

The fifth lodge of the nahurac was known to the Pawnee as Pahur, a name translated as "hill that points the way". According to George Bird Grinnell, the accent is on the second syllable; the "a" in the first syllable is pronounced like the "a" in "father"; and the "u" in the second syllable is pronounced long, like the vowel in "pool".[9]:xxi, 359 In English, the name was shortened to "Guide Rock".[9]:359

Morning Star ceremony

The Morning Star ceremony was a ritual sacrifice of a young girl in the spring. It was connected to the Creation story, in which the mating of the male Morning Star with the female Evening Star created the first human being, a girl.

The ceremony was not held in full every year, but only when a man of the village dreamed that the Morning Star had come to him and told him to perform the ceremony. He then consulted with the Morning Star priest, who has been reading the sky. Together they determined whether the Morning Star was demanding only the more common yearly symbolic ceremony, or requiring that the ceremony be carried out in full. When the Pawnee priests would identify certain celestial bodies on the horizon, they would know that the Morning Star needed to be appeased with the sacrifice of a young girl.

“The sacrifice was performed only in years when Mars was morning star and usually originated in a dream in which the Morning Star appeared to some man and directed him to capture a suitable victim. The dreamer went to the keeper of the Morning Star bundle and received from him the warrior’s costume kept in it. He then set out, accompanied by volunteers, and made a night attack upon an enemy village. As soon as a girl of suitable age was captured the attack ceased and the party returned. The girl was dedicated to the Morning Star at the moment of her capture and was given into the care of the leader of the party who, on its return, turned her over to the chief of the Morning Star.“[12]

Returning to the village, the people treated the girl with respect, but they kept her isolated from the rest of the camp. If it was spring and time for the sacrifice, she was ritually cleansed. What was a five-day ceremony was begun around her. The Morning Star priest would sing songs and the girl was symbolically transformed from human form to be among the celestial bodies. Here the girl became the ritual representation of the Evening Star; she was not impersonating the deity, but instead had become an earthly embodiment. On the final day of the ceremony, a procession of men, boys and even male infants accompanied the girl outside the village to where the men had raised a scaffold. They had used sacred woods and skins, and the scaffold represented “Evening Star’s garden in the west, the source of all animal and plant life.”[13] The priests removed her clothing and

The procession was timed so that she would be left alone on the scaffold at the moment the morning star rose. When the morning star appeared, two men came from the east with flaming brands and touched her lightly in the arm pits and groins. Four other men then touched her with war clubs. The man who had captured her then ran forward with the bow from the Skull bundle and a sacred arrow and shot her through the heart while another man struck her on the head with the war club from the Morning Star bundle. The officiating priest then opened her breast with a flint knife and smeared his face with the blood while her captor caught the falling blood on dried meat. All the male members of the tribe then pressed forward and shot arrows into the body. They then circled the scaffold four times and dispersed.[14]

To fulfill the creation of life, the men of the village would take on the role of the Morning Star, which is why two men would come from the east with flaming brands, representing the sun. The men acted out the violence which had allowed the Morning Star to mate with the Evening Star (by breaking her vaginal teeth) in their creation story, with a “meteor stone.”[15] During the Morning Star ceremony, the captive was shot in the heart and a “man struck her on the head with the war club from the Morning Star bundle.”[15] By having all the men in the village shoot arrows into her body, the village men, embodiments of Morning Star, were symbolically mating with her. Her blood would drip down from the scaffolding and onto the ground which had been made to represent the Evening Star’s garden of all plant and animal life. They took her body and lay the girl face down on the prairie, where her blood would enter the earth and fertilize the ground. The spirit of the Evening Star was released and the men ensured the success of the crops, all life on the Plains, and the perpetuation of the Universe.

Last rites

The Skidi Pawnee practiced the Morning Star ritual regularly through the 1810s. The Missouri Gazette reported a sacrifice in 1818. US Indian agents sought to convince chiefs to suppress the ritual, and major leaders, such as Knife Chief, worked to change the practices objected to by the increasing number of American settlers on the Plains. The last known sacrifice was of Haxti, a 14-year-old Oglala Lakota girl on April 22, 1838.[16]

Notes

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Legendary Native American Figures: Tirawa (Atius Tirawa)". http://www.native-languages.org/home.htm''. Retrieved November 16, 2014.

- ↑ "Atira". The Dinner Party. Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ↑ Weltfish, The Lost Universe: Pawnee Life and Culture, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1965; reprint 1977, p 64

- ↑ Patricia J. O'Brien, "Prehistoric evidence of Pawnee Cosmology", American Anthropologist (New Series) Vol. 88, No. 4 (Dec 1986), pp 939–946

- ↑ Ibid. p 942

- ↑ Alice C. Fletcher, "Star Cult among the Pawnee: A Preliminary Report", American Anthropologist (New Series) Vol 4, No 4 (Oct 1902), pp. 730–736

- ↑ Weltfish, op cit, p. 79

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Grinnell, George Bird (1893). Pawnee Hero Stories and Folk Tales. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. Retrieved 2010-09-16.

- ↑ Jensen, Richard E. (1973). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form: Pahuk".

- ↑ "The History of Waconda". Glen Elder, Kansas. Retrieved 2010-09-16.

- ↑ ">Ralph Linton, "The origin of the Pawnee Morning Star Sacrifice", American Anthropologist.(New Series) Vol 28, No 3 (July 1926), pp 457–466

- ↑ Linton, 1926, p. 458

- ↑ Linton, 1926, p 459

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Weltfish, 1965, p 82

- ↑ Hyde, pp. 19–359

References

- Hyde, George. The Pawnee Indians. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1974. ISBN 0-8061-2094-0