Pavillon de Flore

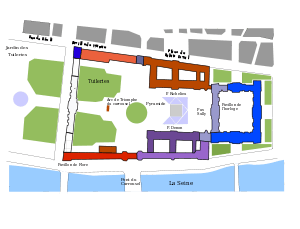

The Pavillon de Flore is a section of the Palais du Louvre in Paris, France. Its construction began in 1607, during the reign of Henry IV, and it has had numerous renovations since. The structure stands along the south face of the Louvre Museum, near the Pont Royal.[1] The Pavillon de Flore was built to extend the Grande Galerie, which formed the south face of the Palais du Louvre, to the Palais des Tuileries, thus linking the two palaces.[2]

The Pavillon played a role in the French Revolution, as many of the executive committees, including the infamous Committee of Public Safety, met there during the Reign of Terror.[3][4] The structure formed the corner edifice of a combined Palais du Louvre and Palais des Tuileries complex until the Palais des Tuileries was destroyed during the Paris Commune insurrection in 1871.[5] Tuileries' destruction affected the aesthetic relationship between the Palais du Louvre and the Arc de Triomphe, as it could now be seen that the two structures were not on the same axis.[6]

History

The cornerstone of the Pavillon de Flore was laid in 1607.[7] Its design has traditionally been assigned to Jacques Androuet II du Cerceau who worked in cooperation with the architect Louis Métezeau. The project was part of a larger plan designed to incorporate the Palais du Louvre and Palais des Tuileries into one complex. The proposal would extend the southern arm of the Palais du Louvre, the Grande Galerie, with a structure that would be named the Pavillon des Tuileries. The northern face, along the Rue de Rivoli, would also be extended, with the Pavillon de Marsan.[2][8] Work on the project was abandoned following the assassination of King Henry IV in 1610.[1] However, by this time, the building of the Pavillon des Tuileries had been completed. King Louis XIV renamed the structure Pavillon de Flore, the name used today despite several changes in between.[1]

The Pavillon de Flore has undergone significant structural alterations since its inception, most notably during the reign of Napoléon III, who in 1861 authorized its remodeling under the supervision of architect Hector Lefuel.[1] The renovation, performed between 1864 and 1868, added significant detail and sculpture to the work, which is thus noted as an example of Second Empire Neo-Baroque architecture.[9][10] Furthermore, Napoléon III commissioned sculptor Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux to create a piece that would evoke "Flore" (in English Flora), the Roman goddess who represents flowers and spring.[11]

Despite the changes to the building, it is the only portion of the Palais des Tuileries complex still in existence. On May 23, 1871, incendiary fires set by twelve members of the Paris Commune, a revolutionary government that briefly ruled Paris from the March 26, 1871 to May 28, 1871, burned the Palais des Tuileries to the ground.[12] The palace's destruction affected the aesthetic relationship between the Palais du Louvre and other buildings in the area. The Palais des Tuileries had served to offset the fact that the Palais du Louvre is skewed slightly 6.33° west of the Axe historique[13] (also known as the Voie Triomphale), a seven-kilometre straight line of structures and thoroughfares, including the Place de la Concorde, Champs-Élysées, the Arc de Triomphe and the Grande Arche de La Défense.[6]

During the course of its life, the Pavillon de Flore has housed numerous notable people and activities. For several years, the apartments of Marie Antoinette were located within the structure and Pope Pius VII also stayed in the building while preparing to crown Napoléon I Emperor of the French.[10] While residing there, the Pope received various "bodies of the State, the clergy, and the religious corporations." Additionally, Emperor Napoléon's procession began at the Pavillon de Flore.[14] Currently, the Pavillon de Flore is notable for being a part of the Musée du Louvre.

French Revolution

During the French Revolution, the Pavillon de Flore, situated at the southwest corner of the Palais des Tuileries at the time, was renamed Pavillon de l'Égalité (House of Equality).[15] Under its new name, it became the meeting point for several of the Committees of the period.[16] Many other committees of the Revolutionary Government occupied the Palais des Tuileries (referred to by contemporaries as the Palace of the Nation) during the time of the National Convention. Notable occupiers included the Monetary Committee, the Account and Liquidation Examination Committee. However, the most famous was the Committee of Public Safety.[17]

Committee of Public Safety

The Committee of Public Safety (French: Comité de salut public) was the principal and most renowned body of the Revolutionary Government, forming the de facto executive branch of France during the Reign of Terror. Run by the Jacobins under Robespierre, the group of twelve centralized denunciations, trials, and executions. The committee was responsible for the deaths of thousands, mostly by guillotine. The executive body was initially installed in the apartments of Marie-Antoinette, situated on the first floor, but also gradually overtook the offices of Louis XVI.[16] The governing body met twice a day and the executions themselves were carried out across the gardens.[17] During the structure's use by the Committee of Public Safety, it was described as follows:

The Committee of Public Safety sat in the Pavillon de Flore, at the opposite end of the Tuileries on the river bank… Any one who had business with this awful body had to grope his way along gloomy corridors, that were dimly lighted by a single lamp at either end. The room in which the Committee sat round a table of green cloth was incongruously gay with the clocks, the bronzes, the mirrors, the tapestries, of the ruined country.— John Morley, [17]

Location

The Pavillon de Flore is in central Paris, on the Right Bank (French: Rive Droite) and is connected to the Louvre. It is directly adjacent to the Pont Royal on the Quai François Mitterrand (formerly Quai du Louvre, renamed Quai François Mitterrand on October 26, 2003), which is between the Passerelle Léopold-Sédar Senghor and the Pont du Carrousel. Its geographic coordinates are 48°51′40″N 2°19′50″E / 48.86111°N 2.33056°ECoordinates: 48°51′40″N 2°19′50″E / 48.86111°N 2.33056°E.

Metro access

| Located near the Métro station: Tuileries. |

| Located near the Métro station: Palais Royal - Musée du Louvre. |

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "Palais du Louvre". International Database and Gallery of Structures (in French). structurae.de. Retrieved 2007-12-19.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Wilhelm Lübke (1904). Outlines of the History of Art. Dodd,Mead, and company. p. 337.

- ↑ Napoleon I, Emperor of the French, 1769-1821 (1934). Letters of Napoleon. p. 144. ISBN 1-84664-918-8.

- ↑ John Morley (Reprint of the 1923 ed.). Biographical Studies. Ayer Publishing. p. 306. ISBN 0-8369-1186-5. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Hugh Chisholm (1911). The Encyclopædia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information. University press. p. 808.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Les Tuileries: Rétablir deux grandes perspectives". Pourquoi Reconstruire? (in French). Comité National pour la reconstruction des Tuileries.

- ↑ Ballon 1991, p. 36.

- ↑ Daniel Coit Gilman; Harry Thurston Peck; Frank Moore Colby. The New International Encyclopaedia. Dodd, Mead and company. p. 622.

- ↑ Philip Gilbert Hamerton (1885). Paris in old and present times. p. 38.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Augustus John Cuthbert Hare (1887). Paris. G.Allen. p. 20.

- ↑ "Official Site of the Louvre" (in French). The Louvre. p. 1. Retrieved 2007-12-19.

...de la face sud du pavillon de Flore reconstruit par Lefuel en 1863 - 1865. Le thème évoque le nom du pavillon...

- ↑ Francis W. Halsey (1914). Seeing Europe with Famous Authors: Volume III - France & the Netherlands - page 19. New York, London: Funk & Wagnalls.

- ↑ Before 1871, the east–west axis of the Palais des Tuileries made the center of its façade the perfect starting point of the Axe historique. However, after the destruction of the palace, the head of the axis fell upon the Palais du Louvre, not on its center but thrown off 6.33°, the angle difference between the axes of the two palaces. But, since the Axe historique was in line with the equestrian statue of Louis XIV which stands in the Cour Carrée of the Louvre, the statue became the new starting point of the Axe historique. For a number of reasons, the axis of the Grande Arche de La Défense happens to have followed the discrepancy of the Louvre: The Arche is turned at an angle of 6.33° on this axis, a peculiarity which has been explained by several theories. In particular the architect is said to have wanted to emphasise the depth of the monument, while the specific angle was chosen to create symmetry with the similarly-skewed Louvre.

- ↑ Claude-François Méneval; Robert Harborough Sherard (1894). Memoirs Illustrating the History of Napoléon I from 1802 to 1815. D. Appleton and Company. p. 329.

- ↑ Eugène Hatin (1860). Histoire politique et littéraire de la presse en France avec une introduction historique sur les origines du journal et de la bibliographie générale des jounaux depuis leur origine, Tome sixième (in French). 9, rue des Beaux-Arts, Paris: Poulet-Malassis et de Broise libraires-éditeurs. p. 151.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Francis Miltoun (1910). Royal Palaces and Parks of France. L.C. Page & Co. pp. 114, 115.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 John Morley (1908). Critical Miscellanies. Macmillan. p. 67.

Sources

- Ballon, Hilary (1991). The Paris of Henri IV: Architecture and Urbanism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-02309-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pavillon de Flore (Palais du Louvre). |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||