Pauli–Lubanski pseudovector

| Quantum field theory |

|---|

Feynman diagram |

| History |

|

Background

|

|

|

Incomplete theories |

|

Scientists

|

In physics, specifically in relativistic quantum mechanics and quantum field theory, the Pauli–Lubanski pseudovector named after Wolfgang Pauli and Józef Lubański[1] is an operator defined from the momentum and angular momentum, used in the quantum-relativistic description of angular momentum. It is the generator of the little group of the Lorentz group, that is the maximal subgroup (with four generators) leaving the eigenvalues of the four-momentum vector Pμ invariant.[2]

Definition

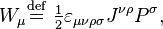

It is usually denoted by W (or less often by S) and defined by:[3][4][5]

where

is the four-dimensional totally antisymmetric Levi-Civita symbol

is the four-dimensional totally antisymmetric Levi-Civita symbol  is the relativistic angular momentum tensor operator

is the relativistic angular momentum tensor operator is the four-momentum.

is the four-momentum.

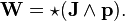

In the language of exterior algebra, it can be written as the Hodge dual of a trivector,[6]

Wμ evidently satisfies

as well as the following commutator relations,

Consequently,

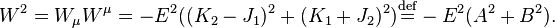

The scalar WμWμ is a Lorentz invariant operator, and commutes with the four-momentum, and can thus serve as a label for irreducible representations of the Lorentz group. That is, it can serve as the label for the spin, a feature of the spacetime structure of the representation, over and above the label (PμPμ) for the mass of states in a representation.

Massive fields

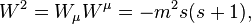

In quantum field theory, in the case of a massive field, the Casimir invariant WμWμ describes the total spin of the particle, with eigenvalues

where s is the spin quantum number of the particle and m is its rest mass.

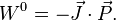

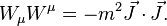

It is straightforward to see this in the rest frame of the particle, where W→ = mJ→ and W0 = 0, so that the little group amounts to the rotation group,

Since this is a Lorentz invariant quantity, it will be the same in all other reference frames. It is also customary to take W3 to describe the spin projection along the third direction in the rest frame.

In moving frames, decomposing W = (W0, W→) into components (W1, W2, W3), with W1 and W2 orthogonal to P→, and W3 parallel to P→, the Pauli–Lubanski vector may be expressed in terms of the spin vector S→ = (S1, S2, S3) (similarly decomposed) as

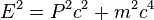

where

is the energy–momentum relation.

The transverse components W1, W2, along with S3, satisfy the following commutator relations (which apply generally, not just to non-zero mass representations),

For particles with non-zero mass, and the fields associated with such particles,

Massless fields

In general, in the case of non-massive representations, two cases may be distinguished. For massless particles,

So, mathematically, P 2 = 0 does not imply W 2 = 0.

In the more general case, the components of W→ transverse to P→ may be non-zero, thus yielding the family of representations referred to as the cylindrical luxons, their identifying property being that the components of W→ form a Lie subalgebra isomorphic to the 2-dimensional Euclidean group ISO(2), with the longitudinal component of W→ playing the role of the rotation generator, and the transverse components the role of translation generators. This amounts to a group contraction of SO(3), and leads to what are known as the continuous spin representations. However, there are no known physical cases of fundamental particles or fields in this family.

In a special case, W→ is parallel to P→; or equivalently W→ × P→ = 0→. For non-zero W→, this constraint can only be consistently imposed for luxons, since the commutator of the two transverse components of W→ is proportional to m2 J→ · P→.

For this family, the helicity operator

represents an invariant, where

All particles that interact with the Weak Nuclear Force, for instance, fall into this family, since the definition of weak nuclear charge ( weak isospin) involves helicity, which, by above, must be an invariant. The appearance of non-zero mass in such cases must then be explained by other means, such as the Higgs mechanism. Even after accounting for such mass-generating mechanisms, however, the photon (and therefore the electromagnetic field) continues to fall into this class, although the other mass eigenstates of the carriers of the electroweak force (the W particle and anti-particle and Z particle) acquire non-zero mass.

Neutrinos were formerly considered to fall into this class as well. However, through neutrino oscillations, it is now known that at least two of the three mass eigenstates of the left-helicity neutrino and right-helicity anti-neutrino each must have non-zero mass.

See also

- Center of mass (relativistic)

- Wigner's classification

- Angular momentum operator

- Casimir operator

- Chirality

- Pseudovector

- Pseudotensor

- Induced representation

References

Notes

- ↑ Lubański, J. K. (1942). "Sur la theorie des particules élémentaires de spin quelconque. I". Physica 9 (3): 310–324. doi:10.1016/S0031-8914(42)90113-7.; Lubanski, J. K. (1942). "Sur la théorie des particules élémentaires de spin quelconque. II". Physica 9 (3): 325–338. doi:10.1016/S0031-8914(42)90114-9.

- ↑ Wigner, Eugene (1939). "On unitary representations of the inhomogeneous Lorentz group". The Annals of Mathematics 40 (1): 149–204. doi:10.2307/1968551.

- ↑ L.H. Ryder (1996). Quantum Field Theory (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 62. ISBN 0-52147-8146.

- ↑ N.N. Bogolubov (1989). General Principles of Quantum Field Theory (2nd ed.). Springer. p. 273. ISBN 0-7923-0540-X.

- ↑ T. Ohlsson (2011). Relativistic Quantum Physics: From Advanced Quantum Mechanics to Introductory Quantum Field Theory. Cambridge University Press. p. 11. ISBN 1-13950-4320.

- ↑ R. Penrose (2005). The Road to Reality. Vintage books. p. 568. ISBN 978-00994-40680.

Other

- Sergeĭ Mikhaĭlovich Troshin, Nikolaĭ Evgenʹevich Ti͡urin (1994). Spin phenomena in particle interactions. World Scientific. ISBN 9-81021-6920.

![\left[P^{\mu},W^{\nu}\right]=0,](../I/m/34159a1c9034a194a454e628abae6e0b.png)

![\left[J^{\mu \nu},W^{\rho}\right]=i \left( g^{\rho \nu} W^{\mu} - g^{\rho \mu} W^{\nu}\right),](../I/m/878453b4886d4a7a916ec23038a24d41.png)

![\left[W_{\mu},W_{\nu}\right]=-i \epsilon_{\mu \nu \rho \sigma} W^{\rho} P^{\sigma}.](../I/m/0bfc47ca794bc9b84fb9b3ef41390099.png)

![[W_1, W_2] = \tfrac{ih}{2\pi} ((E/c^2)^2 - (P/c)^2) S_3, \qquad [W_2, S_3] = \tfrac{ih}{2\pi} W_1, \qquad [S_3, W_1] = \tfrac{ih}{2\pi} W_2.](../I/m/608e998d0785eb048d37d94ca60e2520.png)

![[W_1, W_2] = \tfrac{ih}{2\pi} m^2 S_3.](../I/m/51bccd46e5088aaed318e70fe1d589f3.png)