Patricia Highsmith

| Patricia Highsmith | |

|---|---|

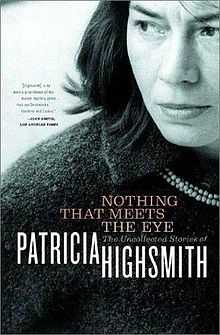

Publicity photo from 1966 | |

| Born |

Mary Patricia Plangman January 19, 1921[1] Fort Worth, Texas, U.S. |

| Died |

February 4, 1995 (aged 74) Locarno, Switzerland |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Nationality | American |

| Period | 1950 onward |

| Genre | Suspense, psychological thriller, crime fiction |

| Subjects | Murder, violence, obsession, insanity |

| Literary movement | Modernist literature |

| Notable works | Strangers on a Train, The Ripliad |

|

| |

| Signature |

|

| Website | |

|

wwnorton groveatlantic | |

Patricia Highsmith (January 19, 1921 – February 4, 1995) was an American novelist and short story writer, most widely known for her psychological thrillers, which led to more than two dozen film adaptations. Her first novel, Strangers on a Train, has been adapted for stage and screen numerous times, notably by Alfred Hitchcock in 1951. In addition to her acclaimed series about murderer Tom Ripley, she wrote many short stories, often macabre, satirical or tinged with black humor. Although she wrote specifically in the genre of crime fiction, her books have been lauded by various writers and critics as being artistic and thoughtful enough to rival mainstream literature. Michael Dirda observed, "Europeans honored her as a psychological novelist, part of an existentialist tradition represented by her own favorite writers, in particular Dostoyevsky, Conrad, Kafka, Gide, and Camus."[2]

Early life

Highsmith was born Mary Patricia Plangman in Fort Worth, Texas, the only child of artists Jay Bernard Plangman (1889–1975) and his wife, the former Mary Coates (September 13, 1895 – March 12, 1991); the couple divorced ten days before their daughter's birth.[3] She was born in her maternal grandmother's boarding house. In 1927, Highsmith, her mother and her adoptive stepfather, artist Stanley Highsmith (whom her mother had married in 1924), moved to New York City.[3] When she was 12 years old, she was taken to Fort Worth and lived with her grandmother for a year. She called this the "saddest year" of her life and felt abandoned by her mother. She returned to New York to continue living with her mother and stepfather, primarily in Manhattan, but she also lived in Astoria, Queens. Patricia Highsmith had an intense, complicated relationship with her mother and largely resented her stepfather. According to Highsmith, her mother once told her that she had tried to abort her by drinking turpentine, although a biography of Highsmith indicates Jay Plangman tried to persuade his wife to have an abortion, but she refused.[4] Highsmith never resolved this love–hate relationship, which haunted her for the rest of her life, and which she fictionalized in her short story "The Terrapin", about a young boy who stabs his mother to death. Highsmith's mother predeceased her by only four years, dying at the age of 95.

Highsmith's grandmother taught her to read at an early age, and Highsmith made good use of her grandmother's extensive library. At the age of eight, she discovered Karl Menninger's The Human Mind and was fascinated by the case studies of patients afflicted with mental disorders such as pyromania and schizophrenia.

Comic books

In 1942, Highsmith graduated from Barnard College, where she had studied English composition, playwriting, and the short story. Living in New York City and Mexico between 1942 and 1948, she wrote for comic book publishers. Answering an ad for "reporter/rewrite", she arrived at the office of comic book publisher Ned Pines and landed a job working in a bullpen with four artists and three other writers. Initially scripting two comic book stories a day for $55-a-week paychecks, she soon realized she could make more money by writing freelance for comics, a situation which enabled her to find time to work on her own short stories and live for a period in Mexico. The comic book scriptwriter job was the only long-term job she ever held.[3]

With Nedor/Standard/Pines (1942–43), she wrote Sgt. Bill King stories and contributed to Black Terror, Real Fact, Real Heroes, and True Comics. She additionally wrote comic book profiles of Einstein, Galileo, Barney Ross, Eddie Rickenbacker, Oliver Cromwell, Sir Isaac Newton, David Livingstone, and others. In 1943–45, she wrote for Fawcett Publications, scripting for such Fawcett Comics characters as the Golden Arrow, Spy Smasher, Captain Midnight, Crisco, and Jasper. She wrote for Western Comics from 1945 to 1947. Under editor Leon Lazarus, she wrote romance comics for the Marvel Comics precursors Timely Comics and Atlas Comics.[5][6]

When she wrote The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955), one of the title character's first scam victims is comic-book artist Frederick Reddington, a parting gesture directed at the earlier career she had abandoned: "Tom had a hunch about Reddington. He was a comic-book artist. He probably didn't know whether he was coming or going."[7]

Novels

Highsmith's first novel was Strangers on a Train, which emerged in 1950, and which contained the violence that became her trademark.[8] At Truman Capote's suggestion, she rewrote the novel at the Yaddo writer's colony in Saratoga Springs, New York.[9] The book proved modestly successful when it was published in 1950. However, Hitchcock's 1951 film adaptation of the novel propelled Highsmith's career and reputation. Soon she became known as a writer of ironic, disturbing psychological mysteries highlighted by stark, startling prose.

Highsmith's second novel, The Price of Salt, was published under the pseudonym Claire Morgan. It garnered wide attention as a lesbian novel because of its rare happy ending.[8] She did not publicly associate herself with this book until late in her life, probably because she had extensively mined her personal life for the book's content.[3]

She was a lifelong diarist, and developed her writing style as a child, writing entries in which she fantasized that her neighbors had psychological problems and murderous personalities behind their façades of normality, a theme she would explore extensively in her novels.

Film and Television Adaptations

As her novels and stories were issued, moviemakers adapted them for screenplays, often in foreign countries, and several more than once.

Her first novel, Strangers on a Train was adapted by Alfred Hitchcock, probably the best-known of all the film adaptations of her work. A television remake in 1996, entitled Once You Meet a Stranger changed the gender of the two lead characters from male to female.[10] An earlier 1969 TV film Once You Kiss a Stranger is loosely based on the same novel, but the novel is not credited. The two leads in this version are a man and a woman.

The first of the 5 Ripley novels was filmed twice, first as a French production in 1960 entitled Plein soleil ("Purple Noon" in English) with Alain Delon as Ripley directed by René Clément, and later as an American production in 1999 with Matt Damon as Ripley directed by Anthony Minghella. The earlier French version was criticized by both author Highsmith and by film critic Roger Ebert for implying that Ripley will be captured by the police.[11][12] However, it made a star out of lead actor Delon, and he became a benchmark against which to judge further performances of Ripley.

The third novel in the Ripliad, Ripley's Game, was also filmed twice, first as a German film in 1977 entitled Der amerikanische Freund ("The American Friend" in English) with Dennis Hopper as Ripley and directed by Wim Wenders. This version also incorporated elements of the second novel Ripley Under Ground.[13] Highsmith initially disliked the film but later changed her mind.[13][14][15] Ripley's Game was filmed a second time as an English language Italian production in 2002 with John Malkovich as Ripley directed by Liliana Cavani. This latter production was released in the US only on home video but not to theatres. Although not all critics were favorable, Roger Ebert regarded it as the best of all the Ripley films to date.[16]

The second novel Ripley Under Ground was filmed in 2005 with Barry Pepper as Ripley, directed by Roger Spottiswoode. It played in the US only at the AFI film festival and then went to DVD. Reviews were scarce.[17]

Although five films have been adapted from three of the Ripley novels, to this date no actor has played Ripley more than once.

All episodes of the 12 episode 1990 series Mistress of Suspense are based on stories by Patricia Highsmith. This series aired first in France, then in the United Kingdom. It is available in the US under the title Chillers and its marketing does not mention that all episodes are Highsmith adaptations. Each episode is introduced by Anthony Perkins in the manner that Alfred Hitchcock introduced each episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents.

Highsmith's Cry of the Owl was filmed twice in 1987, as a German television movie (Der Schrei der Eule) and as an French theatrical movie (Le cri du hibou) directed by Claude Chabrol.

Major themes in her novels

Highsmith included homosexual undertones in many of her novels and addressed the theme directly in The Price of Salt and the posthumously published Small g: a Summer Idyll. The former novel is known for its happy ending, the first of its kind in lesbian fiction. Published in 1952 under the pseudonym Claire Morgan, it sold almost a million copies. The inspiration for the book's main character, Carol, was a woman Highsmith saw in Bloomingdale's department store, where she worked at the time. Highsmith acquired her address from the charge account details, and on two occasions after the book was written (in June 1950 and January 1951) spied on the woman without the latter's knowledge.

The protagonists in many of Highsmith's novels are either morally compromised by circumstance or actively flouting the law. Many of her antiheroes, often emotionally unstable young men, commit murder in fits of passion, or simply to extricate themselves from a bad situation. They are just as likely to escape justice as to receive it. The works of Franz Kafka and Fyodor Dostoevsky played a significant part in her own novels.

Her recurring character Tom Ripley – an amoral, sexually ambiguous con artist and occasional murderer – was featured in a total of five novels, popularly known as the Ripliad, written between 1955 and 1991. He was introduced in The Talented Mr. Ripley.[18] After a 9 January 1956 TV adaptation on Studio One, it was filmed by René Clément as Plein Soleil (1960, aka Purple Noon and Blazing Sun) with Alain Delon, whom Highsmith praised as the ideal Ripley. The novel was adapted under its original title in the 1999 film directed by Anthony Minghella, starring Matt Damon, Gwyneth Paltrow, Jude Law and Cate Blanchett.

A later Ripley novel, Ripley's Game, was filmed by Wim Wenders as The American Friend (1977). Under its original title, it was filmed again in 2002, directed by Liliana Cavani with John Malkovich in the title role. Ripley Under Ground (2005), starring Barry Pepper as Ripley, was shown at the 2005 AFI Film Festival but has not had a general release.

In 2009, BBC Radio 4 adapted all five Ripley books with Ian Hart as Ripley.

Personal life

According to her biography by Andrew Wilson, Beautiful Shadow (2003), Highsmith's personal life was a troubled one; she was an alcoholic who never had an intimate relationship that lasted for more than a few years, and she was seen by some of her contemporaries and acquaintances as misanthropic and cruel. She famously preferred the company of animals to that of people and once said, "My imagination functions much better when I don't have to speak to people."

She loved cats. She bred about three hundred snails in her garden at home in Suffolk, England.[19] Highsmith once attended a London cocktail party with a "gigantic handbag" that "contained a head of lettuce and a hundred snails" who she said were her "companions for the evening".[19]

"She was a mean, hard, cruel, unlovable, unloving person", said acquaintance Otto Penzler. "I could never penetrate how any human being could be that relentlessly ugly."[20]

Other friends and acquaintances were less caustic in their criticism, however; Gary Fisketjon, who published her later novels through Knopf, said that "she was rough, very difficult... but she was also plainspoken, dryly funny, and great fun to be around."[20]

Highsmith had sexual relationships with women and men, but never married or had children. In 1943, she had an affair with the artist Allela Cornell (who committed suicide in 1946 by drinking nitric acid)[21] and in 1949, she became close to novelist Marc Brandel. Between 1959 and 1961 she had a sexual relationship with Marijane Meaker, who wrote under the pseudonyms of Vin Packer and Ann Aldrich but later wrote young adult fiction under the name M.E. Kerr. Meaker wrote of their affair in her memoir, Highsmith: A Romance of the 1950s.

In the late 1980s, after 27 years of separation, Highsmith began sharing correspondence with Meaker again, and one day she showed up on her doorstep, slightly drunk and ranting bitterly. Meaker once recalled in an interview the horror she felt upon noticing the changes in Highsmith's personality by that point.[22]

Highsmith was a "consummate atheist". She was never comfortable with black people, and she was outspokenly anti-semitic – so much so that when she was living in Switzerland in the 1980s, she invented nearly 40 aliases, identities she used in writings sent to various government bodies and newspapers deploring the state of Israel and the "influence" of the Jews.[23] Nevertheless, some of her best friends were Jewish, such as authors Arthur Koestler and Saul Bellow. She was accused of misogyny because of her satirical collection of short stories Little Tales of Misogyny.

Highsmith loved woodworking tools and made several pieces of furniture. She worked without stopping. In later life she became stooped, with an osteoporotic hump.[3] Though her writing – 22 novels and 8 books of short stories – was highly acclaimed, especially outside of the United States, Highsmith preferred for her personal life to remain private. She had friendships and correspondences with several writers, and she was also greatly inspired by art and the animal kingdom.

Highsmith believed in American democratic ideals and in the promise of U.S. history, but she was also highly critical of the reality of the country's 20th-century culture and foreign policy. Tales of Natural and Unnatural Catastrophes, her 1987 anthology of short stories, was notoriously anti-American, and she often cast her homeland in a deeply unflattering light. Beginning in 1963, she resided exclusively in Europe. In 1978, she was head of the jury at the 28th Berlin International Film Festival.[24]

Death

Highsmith died of aplastic anemia and cancer in Locarno, Switzerland, aged 74. She retained her United States citizenship, despite the tax penalties, of which she complained bitterly, from living for many years in France and Switzerland. She was cremated at the cemetery in Bellinzona, and a memorial service was conducted at the Catholic Church in Tegna, Switzerland.[4]

In gratitude to the place which helped inspire her writing career, she left her estate, worth an estimated $3 million, to the Yaddo colony.[8] Her last novel, Small g: a Summer Idyll, was published posthumously a month later. Patricia Highsmith's literary estate is archived in the Swiss Literary Archives in Bern.

Bibliography

Novels

- Strangers on a Train (1950)

- The Price of Salt (as Claire Morgan) (1952), also published as Carol

- The Blunderer (1954)

- Deep Water (1957)

- A Game for the Living (1958)

- This Sweet Sickness (1960)

- The Cry of the Owl (1962)

- The Two Faces of January (1964)

- The Glass Cell (1964)

- A Suspension of Mercy (1965), also published as The Story-Teller

- Those Who Walk Away (1967)

- The Tremor of Forgery (1969)

- A Dog's Ransom (1972)

- Edith's Diary (1977)

- People Who Knock on the Door (1983)

- Found in the Street (1987)

- Small g: a Summer Idyll (1995)

The Ripliad

- The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955)

- Ripley Under Ground (1970)

- Ripley's Game (1974)

- The Boy Who Followed Ripley (1980)

- Ripley Under Water (1991)

Short-story collections

- Eleven (1970; also known as The Snail-Watcher and Other Stories)

- Little Tales of Misogyny (1974)

- The Animal Lover's Book of Beastly Murder (1975)

- Slowly, Slowly in the Wind (1979)

- The Black House (1981)

- Mermaids on the Golf Course (1985)

- Tales of Natural and Unnatural Catastrophes (1987)

- Chillers (1990)

- Nothing That Meets the Eye: The Uncollected Stories (2002; posthumously published)

Collected works

- Patricia Highsmith: Selected Novels and Short Stories (W.W. Norton, 2010)

Miscellaneous

- Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction (1966)

- Miranda the Panda Is on the Veranda (1958; children's book of verse and drawings, co-written with Doris Sanders)

Awards

- 1946 : O. Henry Award for best publication of first story, for "The Heroine" in Harper's Bazaar

- 1951 : Edgar Award nominee for best first novel, for Strangers on a Train

- 1956 : Edgar Award nominee for best novel, for The Talented Mr. Ripley

- 1957 : Grand Prix de Littérature Policière, for The Talented Mr. Ripley

- 1963 : Edgar Award nominee for best short story, for "The Terrapin"

- 1964 : Dagger Award – Category Best Foreign Novel, for The Two Faces of January from the Crime Writers' Association of Great Britain

- 1975 : Grand Prix de l'Humour Noir for L'Amateur d'escargot

- 1990 : Chevalier dans l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres from the French Ministry of Culture

See also

References

- ↑ "United States Social Security Death Index," index, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.1.1/VMGS-2TB : accessed 13 Mar 2013), Mary P Highsmith, 4 February 1995.

- ↑ "This Woman Is Dangerous" The New York Review of Books. July 2, 2009. Accessed November 15, 2009.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Joan Schenkar, "The Misfit and Her Muses", Wall Street Journal, December 8, 2009, p. A19

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Schenkar, Joan (2009), The Talented Miss Highsmith: The Secret Life and Serious Art of Patricia Highsmith, ISBN 978-0-312-30375-4.

- ↑ Leon and Marjorie Lazarus interview, Alter Ego (90): 40. December 2009. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Schenkar, Joan (December 2009). "Patricia Highsmith & The Golden Age of American Comics". Alter Ego (90): 35–39.

- ↑ Highsmith, Patricia. The Talented Mr. Ripley, Vintage Crime/Black Lizard, 1992.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Patricia Cohen, "The Haunts of Miss Highsmith", New York Times, December 10, 2009.

- ↑ Yaddo Writers: June 1926 – December 2007.

- ↑ ONCE YOU MEET A STRANGER Hallmark Channel. Retrieved on 15 October 2010

- ↑ "Purple Noon, rogerebert.com Reviews". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2012-02-22.

- ↑ Wilson, Andrew (2003-05-24). "Ripley's enduring allure". Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-12-30.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Interview with Patricia Highsmith by Gerald Peary

- ↑ The American Friend DVD - Commentary by Wim Wenders, Dennis Hopper - Starz / Anchor Bay, 2003

- ↑ Schenkar, Joan. The Talented Miss Highsmith: The Secret Life and Serious Art of Patricia Highsmith. St. Martin's Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-312-30375-4, page 485-6

- ↑ Ripley's Game :: rogerebert.com :: Great Movies

- ↑ Li, John (21 August 2009). "Ripley Undergrond DVD 2005". movieXclusive.com. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ↑ Coward-McCann, 1955

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Currey, Mason (2013). Daily Rituals. (Borzoi: Knopf) Random House. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-307-27360-4.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Mystery Girl | The Talented Mr. Ripley | Biz | News | Entertainment Weekly

- ↑ Wilson, A. Beautiful Shadow: A Life of Patricia Highsmith. Bloomsbury, London. 2004

- ↑ De Bertodano, Helena (June 16, 2003). "A passion that turned to poison". The Daily Telegraph (London).

- ↑ Winterson, Jeanette (December 20, 2009). "Patricia Highsmith, Hiding in Plain Sight". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Berlinale 1978: Juries". berlinale.de. Retrieved 2010-08-04.

External links

- Publications by and about Patricia Highsmith in the catalogue Helveticat of the Swiss National Library

- Choose Your Highsmith - A Patricia Highsmith Recommendation Engine from W. W. Norton & Company

- Works by or about Patricia Highsmith in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Patricia Highsmith Papers at the Swiss Literary Archives

- This Woman Is Dangerous Michael Dirda on Highsmith and her work from The New York Review of Books

- Patricia Highsmith at the Internet Movie Database

- The Haunts of Miss Highsmith – New York Times – Books

- Hiding in Plain Sight – New York Times Sunday Review of "THE TALENTED MISS HIGHSMITH -The Secret Life and Serious Art of Patricia Highsmith" By Joan Schenkar.

- 1987 RealAudio interview with Patricia Highsmith by Don Swaim (MP3 also available)

- September 1991 interview with Patricia Highsmith by mystery author Michael Dibdin

- 1993 interview with Patricia Highsmith by Naim Attallah

| ||||||||||

|