Passionate Journey

_Passionate_Journey%E2%80%94arriving_on_the_train.jpg) The protagonist arrives at the city by train. | |

| Author | Frans Masereel |

|---|---|

| Original title | Mon livre d'heures |

| Country | Switzerland |

| Genre | Wordless novel |

Publication date | 1919 |

| Pages | 167 (recto only) |

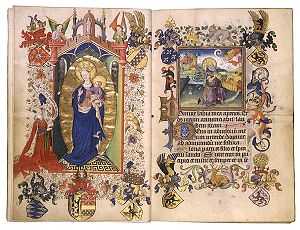

Passionate Journey, or My Book of Hours (French: Mon livre d'heures), is a wordless novel of 1919 by Flemish artist Frans Masereel. The story is told in 167 captionless prints, and is the longest and best-selling of the wordless novels Masereel made. It tells of the experiences of an early 20th-century everyman in a modern city.

Masereel's medium is the woodcut, and the images are in an emotional, allegorical style inspired by Expressionism. The book followed Masereel's first wordless novel, 25 Images of a Man's Passion (1918); both were published in Switzerland, where Masereel spent much of World War I. German publisher Kurt Wolff released an inexpensive "people's edition" of the book in Germany with an introduction by German novelist Thomas Mann, and the book went on to sell over 100,000 copies in Europe. Its success encouraged other publishers to print wordless novels, and the genre flourished in the interwar years.

Masereel followed the book with dozens of others, beginning with The Sun later in 1919. Masereel's work was lauded in the art world in the earlier half of the 20th century, but has since been neglected outside of Western comics circles, where Masereel's wordless novels are seen as anticipating the development of the graphic novel.

Synopsis

The story follows the life of a prototypical early 20th-century everyman after he enters a city. It is by turns comic and tragic: a sick woman cared for by the man loses her life; the man breaks wind at a group of businessmen; the man is rejected by a prostitute with whom he has fallen in love. He also takes trips to different locales around the world.[1] In the end, the man leaves the city for the woods, raises his arms in praise of nature, and dies. His spirit rises from him, stomps on the heart of his dead body, and waves to the reader as it sets off across the universe.[2]

Background

Frans Masereel (1889–1972)[3] was born into a French-speaking family[4] in Blankenberge, Belgium. At five his father died, and his mother remarried to a doctor in Ghent, whose political beliefs left an impression on the young Masereel. He often accompanied his stepfather in socialist demonstrations. After a year at the Ghent Academy of Fine Arts in 1907, Masereel left to study art on his own in Paris.[3] During World War I he volunteered as a translator for the Red Cross in Geneva, drew newspaper political cartoons, and copublished a magazine Les Tablettes, in which he published his first woodcut prints.[5]

In the early 20th century there was a revival in interest in mediaeval woodcuts, particularly in religious books such as the Biblia pauperum.[6] The woodcut is a less refined medium than the wood engraving that replaced it—artists of the time took to the rougher woodcut to express angst and frustration.[7] From 1917 Masereel began publishing books of woodcut prints,[8] using similar imagery to make political statements on the strife of the common people rather than to illustrate the lives of Christ and the saints.[7] In 1918 he created the first such book to feature a narrative, 25 Images of a Man's Passion.[8] He followed its success in 1919 with Passionate Journey, which remained his favourite of his own works.[5]

Publication history

The black-and-white woodcut images in the book were each 9 by 7 centimetres (3 1⁄2 in × 2 3⁄4 in).[1] Masereel self-published the book in Geneva on credit from Swiss printer Albert Kundig[9] in 1919 as Mon livre d'heures[10] in an edition of 200 copies. It was printed directly from the original woodblocks.[11]

German publisher Kurt Wolff sent Hans Mardersteig to Masereel to arrange German publication[12] in 1920.[9] It was printed from the original woodblocks[11] in an edition of 700 copies under the title Mein Stundenbuch: 165 Holzschnitte,[10] Wolff thereafter continued to publish German editions of Masereel's books,[12] later in inexpensive "people's editions" using electrotype reproduction. The 1926 edition had an introduction by German writer Thomas Mann:[11]

Look at these powerful black-and-white figures, their features etched in light and shadow. You will be captivated from beginning to end: from the first pictured showing the train plunging through the dense smoke and bearing the hero toward life, to the very last picture showing the skeleton-faced figure among the stars. Has not this passionate journey had an incomparably deeper and purer impact on you than you have ever felt before?[13][lower-alpha 1]

_Passionate_Journey_urination_page.jpg)

The German edition was particularly popular, and went through several editions in the 1920s with sales surpassing 100,000 copies. Its success prompted other publishers and artists to produce wordless novels.[10]

The book won an English-speaking audience after its 1922 US publication under the title My Book of Hours.[14] printed from the original woodblocks[11] in an edition of 600 copies with a foreword by French writer Romain Rolland.[11] English-language editions took the title Passionate Journey[10] after publication in a popular edition in the US in 1948. An edition did not see print in England until Redstone Press published one in the 1980s.[14] It has also appeared in many other languages,[15] including Chinese popular editions in 1933 and 1957.[12] Some editions since 1928 have cut two pages from the book: the 24th, in which the protogonist has sex with a prostitute; and the 149th, in which the protagonist, giant-sized, urinates on the city.[16] Dover Publications restored the pages in a 1971 edition, and American editions since then have kept them.[17]

Style and analysis

I believe that it contained the essence of what I wanted to say; I expressed my philosophy, and perhaps My Book of Hours with its 167 woodcuts contains everything I have created since, because I have developed a number of themes from it in my later work.[12][lower-alpha 2]—Frans Masereel, Interview with Pierre Vorms, 1967

Masereel uses an emotional, Expressionistic style to create a narrative replete with allegory, satire, and social criticism—a visual style he continued with throughout his career. He expresses a broad variety of emotions through understated, unexaggerated gestures. Most characters are given simple, passive expressions, which provides emphatic contrast with characters expressing more explicit emotion—love, despair, ecstasy.[12] He considered Passionate Journey partly autobiographical,[18] which he emphasized with a pair of self-portraits that open the book—in the first, Masereel sits at his desk with his woodcutting tools, and in the second appears the protagonist, dressed in identical fashion with the first.[16] Literature scholar Martin S. Cohen wrote that it expressed themes that were to become universal in the wordless novel genre.[18]

The original titles of Masereel's first two wordless novels allude to religious works: 25 Images of a Man's Passion to the Passion of Christ, and My Book of Hours to the mediaeval devotional book of hours. These religious books made frequent use of allegory, also prominent in Masereel's works—though Masereel replaces the religious archetypes of mediaeval morality plays with those from socialist ideology.[19] The book derives some of its visual vocabulary—framing, sequencing, and viewpoints—from silent film. Thomas Mann named the book his favourite film.[20]

Wordless novel scholar David Beronä saw the work as a catalogue of human activity, and in this regard compared it to Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass and Allen Ginsberg's Howl.[21] Austrian writer Stefan Zweig remarked, "If everything were to perish, all the books, monuments, photographs and memoirs, and only the woodcuts that [Masereel] has executed in ten years were spared, our whole present-day world could be reconstructed from them."[22] Critic Chris Lanier attributes the protagonist's appeal to readers to Masereel's avoiding a preaching tone in the work; "rather", Lanier states, "he gives us a story as a device through which we can examine ourselves".[23] This openness in the images invites individual interpretation, according to Beronä.[2]

In contrast to the works of Masereel's imitators, the images do not form an unfolding sequence of actions but are rather like individual snapshots of events in the protagonist's life.[19] The book opens with a pair of literary quotations:[16]

Behold! I do not give lectures, or a little charity: When I give, I give myself.

... des plaisirs et des peines, des malices, facéties, expériences et folies, de la paille et du foin, des figues et du raisin, des fruits verts, des fruits doux, des roses et des gratte-culs, des choses vues, et lues, et sues, et eues, vécues![lower-alpha 3]

Reception and legacy

_Passionate_Journey%E2%80%94final_panel.jpg)

Impressed by the book, German publisher Kurt Wolff arranged for its German publication and continued to publish German editions of Masereel's books.[12] Wolf's edition of Passionate Journey went through multiple printings, and the book was popular throughout Europe, where it sold over 100,000 copies.[13] Soon other publishers also engaged in the publication of wordless novels,[12] though none matched the success of Masereel's,[6] which Beronä has called "perhaps the most seminal work in the genre".[15]

While not as successful at first in the United States, American reviewers recognized Masereel as father of the wordless novel at least as early as the 1930s.[14] A revival in publishing interest in wordless novels in the 1970s saw Passionate Journey the most frequently reprinted.[24]

While the graphic narrative bears strong similarities to the comics that were proliferating in the early 20th century, Masereel's book emerged from a fine arts environment and was aimed at such an audience. Its influence was felt not in comics but in the worlds of literature, film, music, and advertising.[25] Masereel's work was widely recognized with awards and exhibitions in the early 20th century, but has since been mostly forgotten outside of Western comics circles,[26] where his wordless novels, and Passionate Journey in particular, are seen as precursors to the graphic novel.[27]

Notes

- ↑ German: Laßt seine kräftig schwarz-weißen, licht-und schattenbewegten Gesichte ablaufen, vom ersten angefangen, vom dem im Qualme schief dahinbrausenden Eisenbahnwagen, der den Helden ins Leben trägt, bis zu dem Sternenbummel eines Entfleischten zu guter Letzt; wo seid ihr? Von welcher allbeliebten Unterhaltung glaubt ihr euch hingenommen, wenn auch auf unvergleichlich innigere und reinere Weise hingenommen, als es euch dort denn doch wohl je zuteil geworden?[10]

- ↑ German: Ich glaube, daß darin das Wesentliche von dem liegt, was ich sagen wollte; ich drückte darin ein wenig meine Philosophie aus, vielleicht enthält Mein Studenbuch mit seinen 167 Holzschintten potentiell alles das, was ich danach geschaffen habe, denn ich habe wo anders und später eine ganze Anzahl von Themen daraus entwickelt.[13]

- ↑ ... joy and sorrow, spite and good-humor, wisdom and folly, hay and straw, figs and grapes, fruit ripe and unripe, roses and haws — what I have seen, felt and known, owned and lived ... (Katherine Miller translation, 1919)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Beronä 2008, p. 21.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Beronä 2008, p. 22.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Beronä 2007, p. v.

- ↑ Willett 2005, p. 132.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Beronä 2007, p. vi.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Willett 2005, p. 126.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Willett 2005, p. 127.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Beronä 2007, pp. vi–vii.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Beronä 2003, p. 63.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Willett 2005, p. 114.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Antonsen 2004, p. 154.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 Willett 2005, p. 118.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Willett 2005, p. 116.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Willett 1997, p. 19.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Beronä 2008, p. 24.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Cohen 1977, p. 184.

- ↑ Beronä 2003, p. 64.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Cohen 1977, p. 183.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Petersen 2010, p. 63.

- ↑ Willett 2005, p. 129.

- ↑ Beronä 2003, pp. 64–65.

- ↑ Beronä 2003, p. 65.

- ↑ Lanier 1998, p. 114.

- ↑ Willett 1997, p. 12.

- ↑ Mehring 2013, pp. 217–218.

- ↑ Antonsen 2004, p. 155.

- ↑ Antonsen 2004, p. 155; Tabachnick 2010, p. 3.

Works cited

- Antonsen, Lasse B. (2004). "Frans Masereel: Passionate Journey". Harvard Review (27): 154–155. JSTOR 27568954.

- Beronä, David A. (March 2003). "Wordless Novels in Woodcuts". Print Quarterly (Print Quarterly Publications) 20 (1): 61–73. JSTOR 41826477.

- Beronä, David A. (2008). Wordless Books: The Original Graphic Novels. Abrams Books. ISBN 978-0-8109-9469-0.

- Cohen, Martin S. (April 1977). "The Novel in Woodcuts: A Handbook". Journal of Modern Literature 6 (2): 171–195. JSTOR 3831165.

- Lanier, Chris (November 1998). "Frans Masereel: A Thousand Words". The Comics Journal (Fantagraphics Books): 109–117.

- Beronä, David (2007). "Introduction". In Beronä, David. Frans Masereel: Passionate Journey: A Vision in Woodcuts. Dover Publications. pp. v–ix. ISBN 978-0-486-13920-3.

- Mehring, Frank (2013). "Hard-Boiled Silhouettes". In Denson, Shane; Meyer, Christina; Stein, Daniel. Transnational Perspectives on Graphic Narratives: Comics at the Crossroads. A&C Black. pp. 211–228. ISBN 978-1-4411-8575-4.

- Petersen, Robert (2010). Comics, Manga, and Graphic Novels: A History of Graphic Narratives. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-36330-6.

- Tabachnick, Stephen E. (2010). "The Graphic Novel and the Age of Transition: A Survey and Analysis" (PDF). English Literature in Transition, 1880-1920 53 (1): 3–28. doi:10.2487/elt.53.1(2010)0050.

- Willett, Perry (1997). The Silent Shout: Frans Masereel, Lynd Ward, and the Novel in Woodcuts. Indiana University Libraries.

- Willett, Perry (2005). "The Cutting Edge of German Expressionism: The Woodcut Novel of Frans Masereel and Its Influences". In Donahue, Neil H. A Companion to the Literature of German Expressionism. Camden House. pp. 111–134. ISBN 978-1-57113-175-1.

| ||||||||||||||