Partition of India

The Partition of India was the partition of the British Indian Empire[1] that led to the creation of the sovereign states of the Dominion of Pakistan (it later split into the Islamic Republic of Pakistan and the People's Republic of Bangladesh) and the Union of India (later Republic of India) on 15 August 1947. "Partition" here refers not only to the division of the Bengal province of British India into East Pakistan and West Bengal (India), and the similar partition of the Punjab province into Punjab (West Pakistan) and Punjab, India, but also to the respective divisions of other assets, including the British Indian Army, the Indian Civil Service and other administrative services, the railways, and the central treasury.

In the riots which preceded the partition in the Punjab region, between 200,000 to 500,000 people were killed in the retributive genocide.[2][3] UNHCR estimates 14 million Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims were displaced during the partition; it was the largest mass migration in human history.[4][5][6]

The secession of Bangladesh from Pakistan in 1971 is not covered by the term Partition of India, nor is the earlier separation of Burma (now Myanmar) from the administration of British India, or the even earlier separation of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). Ceylon was part of the Madras Presidency of British India from 1795 until 1798 when it became a separate Crown Colony of the Empire. Burma, gradually annexed by the British during 1826–86 and governed as a part of the British Indian administration until 1937, was directly administered thereafter.[7] Burma was granted independence on 4 January 1948 and Ceylon on 4 February 1948. (See History of Sri Lanka and History of Burma.)

Bhutan, Nepal and the Maldives, the remaining countries of present-day South Asia, were unaffected by the partition. The first two, Nepal and Bhutan, having signed treaties with the British designating them as independent states, were never a part of the British Indian Empire, and therefore their borders were unaffected by the partition of India.[8] The Maldives, which had become a protectorate of the British crown in 1887 and gained its independence in 1965, was also unaffected by the partition.

Background

Partition of Bengal (1905)

|

In 1905, the viceroy, Lord Curzon, who was considered by some to be both brilliant and indefatigable, and who in his first term had built an impressive record of archaeological preservation and administrative efficiency, now, in his second term, divided the largest administrative subdivision in British India, the Bengal Presidency, into the Muslim-majority province of East Bengal and Assam and the Hindu-majority province of Bengal (present-day Indian states of West Bengal, Bihār, Jharkhand and Odisha).[9] Curzon's act, the Partition of Bengal—which some considered administratively felicitous, and, which had been contemplated by various colonial administrations since the time of Lord William Bentinck, but never acted upon—was to transform nationalist politics as nothing else before it.[9] The Hindu elite of Bengal, among them many who owned land in East Bengal that was leased out to Muslim peasants, protested fervidly. The large Bengali Hindu middle-class (the Bhadralok), upset at the prospect of Bengalis being outnumbered in the new Bengal province by Biharis and Oriyas, felt that Curzon's act was punishment for their political assertiveness.[9] The pervasive protests against Curzon's decision took the form predominantly of the Swadeshi ("buy Indian") campaign led by two-time Congress president, Surendranath Banerjee, and involved boycott of British goods. Sporadically—but flagrantly—the protesters also took to political violence that involved attacks on civilians.[10] The violence, however, was not effective, most planned attacks were either preempted by the British or failed.[11] The rallying cry for both types of protest was the slogan Bande Mataram (Bengali, lit: "Hail to the Mother"), the title of a song by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, which invoked a mother goddess, who stood variously for Bengal, India, and the Hindu goddess Kali.[12] The unrest spread from Calcutta to the surrounding regions of Bengal when Calcutta's English-educated students returned home to their villages and towns.[13] The religious stirrings of the slogan and the political outrage over the partition were combined as young men, in groups such as Jugantar, took to bombing public buildings, staging armed robberies,[11] and assassinating British officials.[12] Since Calcutta was the imperial capital, both the outrage and the slogan soon became nationally known.[12]

The overwhelming, but predominantly Hindu, protest against the partition of Bengal and the fear, in its wake, of reforms favouring the Hindu majority, now led the Muslim elite in India, in 1906, to meet with the new viceroy, Lord Minto, and to ask for separate electorates for Muslims. In conjunction, they demanded proportional legislative representation reflecting both their status as former rulers and their record of cooperating with the British. This led, in December 1906, to the founding of the All-India Muslim League in Dacca. Although Curzon, by now, had resigned his position over a dispute with his military chief Lord Kitchener and returned to England, the League was in favour of his partition plan. The Muslim elite's position, which was reflected in the League's position, had crystallized gradually over the previous three decades, beginning with the 1871 Census of British India, which had first estimated the populations in regions of Muslim majority.[14] (For his part, Curzon's desire to court the Muslims of East Bengal had arisen from British anxieties ever since the 1871 census—and in light of the history of Muslims fighting them in the 1857 Mutiny and the Second Anglo-Afghan War—about Indian Muslims rebelling against the Crown.[14]) In the three decades since that census, Muslim leaders across northern India, had intermittently experienced public animosity from some of the new Hindu political and social groups.[14] The Arya Samaj, for example, had not only supported Cow Protection Societies in their agitation,[15] but also—distraught at the 1871 Census's Muslim numbers—organized "reconversion" events for the purpose of welcoming Muslims back to the Hindu fold.[14] In UP, Muslim became anxious when, in the late 19th century, political representation increased, giving more power to Hindus, and Hindus were politically mobilized in the Hindi-Urdu controversy and the anti-cow-killing riots of 1893.[16] In 1905, when Tilak and Lajpat Rai attempted to rise to leadership positions in the Congress, and the Congress itself rallied around symbolism of Kali, Muslim fears increased.[14] It was not lost on many Muslims, for example, that the rallying cry, "Bande Mataram," had first appeared in the novel Anand Math in which Hindus had battled their Muslim oppressors.[17] Lastly, the Muslim elite, and among it Dacca Nawab, Khwaja Salimullah, who hosted the League's first meeting in his mansion in Shahbag, was aware that a new province with a Muslim majority would directly benefit Muslims aspiring to political power.[17]

World War I, Lucknow Pact: 1914–1918

|

World War I would prove to be a watershed in the imperial relationship between Britain and India. 1.4 million Indian and British soldiers of the British Indian Army would take part in the war and their participation would have a wider cultural fallout: news of Indian soldiers fighting and dying with British soldiers, as well as soldiers from dominions like Canada and Australia, would travel to distant corners of the world both in newsprint and by the new medium of the radio.[18] India's international profile would thereby rise and would continue to rise during the 1920s.[18] It was to lead, among other things, to India, under its own name, becoming a founding member of the League of Nations in 1920 and participating, under the name, "Les Indes Anglaises" (British India), in the 1920 Summer Olympics in Antwerp.[19] Back in India, especially among the leaders of the Indian National Congress, it would lead to calls for greater self-government for Indians.[18]

The 1916 Lucknow Session of the Congress was also the venue of an unanticipated mutual effort by the Congress and the Muslim League, the occasion for which was provided by the wartime partnership between Germany and Turkey. Since the Turkish Sultan, or Khalifah, had also sporadically claimed guardianship of the Islamic holy sites of Mecca, Medina, and Jerusalem, and since the British and their allies were now in conflict with Turkey, doubts began to increase among some Indian Muslims about the "religious neutrality" of the British, doubts that had already surfaced as a result of the reunification of Bengal in 1911, a decision that was seen as ill-disposed to Muslims.[20] In the Lucknow Pact, the League joined the Congress in the proposal for greater self-government that was campaigned for by Tilak and his supporters; in return, the Congress accepted separate electorates for Muslims in the provincial legislatures as well as the Imperial Legislative Council. In 1916, the Muslim League had anywhere between 500 and 800 members and did not yet have its wider following among Indian Muslims of later years; in the League itself, the pact did not have unanimous backing, having largely been negotiated by a group of "Young Party" Muslims from the United Provinces (UP), most prominently, two brothers Mohammad and Shaukat Ali, who had embraced the Pan-Islamic cause;[20] however, it did have the support of a young lawyer from Bombay, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who was later to rise to leadership roles in both the League and the Indian independence movement. In later years, as the full ramifications of the pact unfolded, it was seen as benefiting the Muslim minority élites of provinces like UP and Bihar more than the Muslim majorities of Punjab and Bengal, nonetheless, at the time, the "Lucknow Pact," was an important milestone in nationalistic agitation and was seen so by the British.[20]

Montague–Chelmsford Reforms: 1919

Montague and Chelmsford presented their report in July 1918 after a long fact-finding trip through India the previous winter.[21] After more discussion by the government and parliament in Britain, and another tour by the Franchise and Functions Committee for the purpose of identifying who among the Indian population could vote in future elections, the Government of India Act of 1919 (also known as the Montague-Chelmsford Reforms) was passed in December 1919.[21] The new Act enlarged both the provincial and Imperial legislative councils and repealed the Government of India's recourse to the "official majority" in unfavorable votes.[21] Although departments like defense, foreign affairs, criminal law, communications, and income-tax were retained by the Viceroy and the central government in New Delhi, other departments like public health, education, land-revenue, local self-government were transferred to the provinces.[21] The provinces themselves were now to be administered under a new dyarchical system, whereby some areas like education, agriculture, infrastructure development, and local self-government became the preserve of Indian ministers and legislatures, and ultimately the Indian electorates, while others like irrigation, land-revenue, police, prisons, and control of media remained within the purview of the British governor and his executive council.[21] The new Act also made it easier for Indians to be admitted into the civil service and the army officer corps.

A greater number of Indians were now enfranchised, although, for voting at the national level, they constituted only 10% of the total adult male population, many of whom were still illiterate.[21] In the provincial legislatures, the British continued to exercise some control by setting aside seats for special interests they considered cooperative or useful. In particular, rural candidates, generally sympathetic to British rule and less confrontational, were assigned more seats than their urban counterparts.[21] Seats were also reserved for non-Brahmins, landowners, businessmen, and college graduates. The principal of "communal representation," an integral part of the Minto-Morley Reforms, and more recently of the Congress-Muslim League Lucknow Pact, was reaffirmed, with seats being reserved for Muslims, Sikhs, Indian Christians, Anglo-Indians, and domiciled Europeans, in both provincial and Imperial legislative councils.[21] The Montague-Chelmsford reforms offered Indians the most significant opportunity yet for exercising legislative power, especially at the provincial level; however, that opportunity was also restricted by the still limited number of eligible voters, by the small budgets available to provincial legislatures, and by the presence of rural and special interest seats that were seen as instruments of British control.[21]

Muslim homeland, provincial elections, World War II, Lahore resolution: 1930–1945

|

Although Choudhry Rahmat Ali had in 1933 produced a pamphlet, Now or never, in which the term "Pakistan," "the land of the pure," comprising the Punjab, North West Frontier Province (Afghania), Kashmir, Sindh, and Balochistan, was coined for the first time, the pamphlet did not attract political attention.[22] A little later, a Muslim delegation to the Parliamentary Committee on Indian Constitutional Reforms, gave short shrift to the Pakistan idea, calling it "chimerical and impracticable."[22]

Two years later, the Government of India Act 1935 introduced provincial autonomy, increasing the number of voters in India to 35 million.[23] More significantly, law and order issues were for the first time devolved from British authority to provincial governments headed by Indians.[23] This increased Muslim anxieties about eventual Hindu domination.[23] In the Indian provincial elections, 1937, the Muslim League turned out its best performance in Muslim-minority provinces such as the United Provinces, where it won 29 of the 64 reserved Muslim seats.[23] However, in the Muslim-majority regions of the Punjab and Bengal regional parties outperformed the League.[23] In the Punjab, the Unionist Part of Sikandar Hayat Khan, won the elections and formed a government, with the support of the Indian National Congress and the Shiromani Akali Dal, which lasted five years.[23] In Bengal, the League had to share power in a coalition headed by A. K. Fazlul Huq, the leader of the Krishak Praja Party.[23]

The Congress, on the other hand, with 716 wins in the total of 1585 provincial assemblies seats, was able to form governments in 7 out of the 11 provinces of British India.[23] In its manifesto the Congress maintained that religious issues were of lesser importance to the masses than economic and social issues, however, the election revealed that the Congress had contested just 58 out of the total 482 Muslim seats, and of these, it won in only 26.[23] In UP, where the Congress won, it offered to share power with the League on condition that the League stop functioning as a representative only of Muslims, which the League refused.[23] This proved to be a mistake as it alienated the Congress further from the Muslim masses. In addition, the new UP provincial administration promulgated cow protection and the use of Hindi.[23] The Muslim elite in UP was further alienated, when they saw chaotic scenes of the new Congress Raj, in which rural people who sometimes turned up in large numbers in Government buildings, were indistinguishable from the administrators and the law enforcement personnel.[24]

The Muslim League conducted its own investigation into the conditions of Muslims under Congress-governed provinces.[25] Although its reports were exaggerated, it increased fear among the Muslim masses of future Hindu domination.[25] The view that Muslims would be unfairly treated in an independent India dominated by the Congress was now a part of the public discourse of Muslims.[25] With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, the viceroy, Lord Linlithgow, declared war on India's behalf without consulting Indian leaders, leading the Congress provincial ministries to resign in protest.[25] The Muslim League, which functioned under state patronage,[26] in contrast, organized "Deliverance Day," celebrations (from Congress dominance) and supported Britain in the war effort.[25] When Linlithgow, met with nationalist leaders, he gave the same status to Jinnah as he did to Gandhi, and a month later described the Congress as a "Hindu organization."[26]

In March 1940, in the League's annual three-day session in Lahore, Jinnah gave a two-hour speech in English, in which were laid out the arguments of the Two-nation theory, stating, in the words of historians Talbot and Singh, that "Muslims and Hindus ... were irreconcilably opposed monolithic religious communities and as such no settlement could be imposed that did not satisfy the aspirations of the former."[25] On the last day of its session, the League passed, what came to be known as the Lahore Resolution, sometimes also "Pakistan Resolution,"[25] demanding that, "the areas in which the Muslims are numerically in majority as in the North-Western and Eastern zones of India should be grouped to constitute independent states in which the constituent units shall be autonomous and sovereign." Though it had been founded more than three decades earlier, the League would gather support among South Asian Muslims only during the Second World War.[27]

In March 1942, with the Japanese fast moving up the Malayan Peninsula after the Fall of Singapore,[26] and with the Americans supporting independence for India,[28] Winston Churchill, the wartime Prime Minister of Britain, sent Sir Stafford Cripps, the leader of the House of Commons, with an offer of dominion status to India at the end of the war in return for the Congress's support for the war effort.[29] Not wishing to lose the support of the allies they had already secured—the Muslim League, Unionists of the Punjab, and the Princes—the Cripps offer included a clause stating that no part of the British Indian Empire would be forced to join the post-war Dominion. As a result of the proviso, the proposals were rejected by the Congress, which, since its founding as a polite group of lawyers in 1885,[27] saw itself as the representative of all Indians of all faiths.[29] After the arrival in 1920 of Gandhi, the preeminent strategist of Indian nationalism,[30] the Congress had been transformed into a mass nationalist movement of millions.[27] In August 1942, the Congress launched the Quit India Resolution which asked for drastic constitutional changes, which the British saw as the most serious threat to their rule since the Indian rebellion of 1857.[29] With their resources and attention already spread thin by a global war, the nervous British immediately jailed the Congress leaders and kept them in jail until August 1945,[31] whereas the Muslim League was now free for the next three years to spread its message.[26] Consequently, the Muslim League's ranks surged during the war, with Jinnah himself admitting, "The war which nobody welcomed proved to be a blessing in disguise."[32] Although there were other important national Muslim politicians such as Congress leader Ab'ul Kalam Azad, and influential regional Muslim politicians such as A. K. Fazlul Huq of the leftist Krishak Praja Party in Bengal, Sikander Hyat Khan of the landlord-dominated Punjab Unionist Party, and Abd al-Ghaffar Khan of the pro-Congress Khudai Khidmatgar (popularly, "red shirts") in the North West Frontier Province, the British were to increasingly see the League as the main representative of Muslim India.[33]

Cabinet Mission, Direct Action Day, Plan for Partition, Independence 1946–1947

|

In January 1946, a number of mutinies broke out in the armed services, starting with that of RAF servicemen frustrated with their slow repatriation to Britain.[34] The mutinies came to a head with mutiny of the Royal Indian Navy in Bombay in February 1946, followed by others in Calcutta, Madras, and Karachi. Although the mutinies were rapidly suppressed, they had the effect of spurring the new Labour government in Britain to action, and leading to the Cabinet Mission to India led by the Secretary of State for India, Lord Pethick Lawrence, and including Sir Stafford Cripps, who had visited four years before.[34] Also in early 1946, new elections were called in India. Earlier, at the end of the war in 1945, the colonial government had announced the public trial of three senior officers of Subhas Chandra Bose's defeated Indian National Army who stood accused of treason. Now as the trials began, the Congress leadership, although ambivalent towards the INA, chose to defend the accused officers.[35] The subsequent convictions of the officers, the public outcry against the convictions, and the eventual remission of the sentences, created positive propaganda for the Congress, which only helped in the party's subsequent electoral victories in eight of the eleven provinces.[36] The negotiations between the Congress and the Muslim League, however, stumbled over the issue of the partition.

Jinnah proclaimed 16 August 1946, Direct Action Day, with the stated goal of highlighting, peacefully, the demand for a Muslim homeland in British India. However, on the morning of the 16th armed Muslim gangs gathered at the Ochterlony Monument in Calcutta to hear Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, the League's Chief Minister of Bengal, who, in the words of historian Yasmin Khan, "if he did not explicitly incite violence certainly gave the crowd the impression that they could act with impunity, that neither the police nor the military would be called out and that the ministry would turn a blind eye to any action they unleashed in the city."[37] That very evening, in Calcutta, Hindus were attacked by returning Muslim celebrants, who carried pamphlets distributed earlier showing a clear connection between violence and the demand for Pakistan, and implicating the celebration of Direct Action day directly with the outbreak of the cycle of violence that would be later called the "Great Calcutta Killing of August 1946".[38] The next day, Hindus struck back and the violence continued for three days in which approximately 4,000 people died (according to official accounts), Hindus and Muslims in equal numbers. Although India had had outbreaks of religious violence between Hindus and Muslims before, the Calcutta killings was the first to display elements of "ethnic cleansing," in modern parlance.[39] Violence was not confined to the public sphere, but homes were entered, destroyed, and women and children attacked.[40] Although the Government of India and the Congress were both shaken by the course of events, in September, a Congress-led interim government was installed, with Jawaharlal Nehru as united India's prime minister.

The communal violence spread to Bihar (where Muslims were attacked by Hindus), to Noakhali in Bengal (where Hindus were targeted by Muslims), in Garhmukteshwar in the United Provinces (where Muslims were attacked by Hindus), and on to Rawalpindi in March 1947 in which Hindus were attacked or driven out by Muslims.[39] Late in 1946, the Labour government in Britain, its exchequer exhausted by the recently concluded World War II, decided to end British rule of India, and in early 1947 Britain announced its intention of transferring power no later than June 1948. However, with the British army unprepared for the potential for increased violence, the new viceroy, Louis Mountbatten, advanced the date for the transfer of power, allowing less than six months for a mutually agreed plan for independence. In June 1947, the nationalist leaders, including Nehru and Abul Kalam Azad on behalf of the Congress, Jinnah representing the Muslim League, B. R. Ambedkar representing the Untouchable community, and Master Tara Singh representing the Sikhs, agreed to a partition of the country along religious lines in stark opposition to Gandhi's views. The predominantly Hindu and Sikh areas were assigned to the new India and predominantly Muslim areas to the new nation of Pakistan; the plan included a partition of the Muslim-majority provinces of Punjab and Bengal. The communal violence that accompanied the announcement of the Radcliffe Line, the line of partition, was even more horrific.

Of the violence that accompanied the Partition of India, historians Ian Talbot and Gurharpal Singh write:

There are numerous eyewitness accounts of the maiming and mutilation of victims. The catalogue of horrors includes the disembowelling of pregnant women, the slamming of babies' heads against brick walls, the cutting off of victims limbs and genitalia and the display of heads and corpses. While previous communal riots had been deadly, the scale and level of brutality was unprecedented. Although some scholars question the use of the term 'genocide' with respect to the Partition massacres, much of the violence manifested as having genocidal tendencies. It was designed to cleanse an existing generation as well as prevent its future reproduction."[41]

On 14 August 1947, the new Dominion of Pakistan came into being, with Muhammad Ali Jinnah sworn in as its first Governor General in Karachi. The following day, 15 August 1947, India, now a smaller Union of India, became an independent country with official ceremonies taking place in New Delhi, and with Jawaharlal Nehru assuming the office of the prime minister, and the viceroy, Louis Mountbatten, staying on as its first Governor General; Gandhi, however, remained in Bengal, preferring instead to work among the new refugees of the partitioned subcontinent.

Geographic partition, 1947

Mountbatten Plan

The actual division of British India between the two new dominions was accomplished according to what has come to be known as the 3 June Plan or Mountbatten Plan. It was announced at a press conference by Mountbatten on 3 June 1947, when the date of independence was also announced – 15 August 1947. The plan's main points were:

- Sikhs, Hindus and Muslims in Punjab and Bengal legislative assemblies would meet and vote for partition. If a simple majority of either group wanted partition, then these provinces would be divided.

- Sindh was to take its own decision.

- The fate of North West Frontier Province and Sylhet district of Assam was to be decided by a referendum.

- India would be independent by 15 August 1947.

- The separate independence of Bengal was ruled out.

- A boundary commission to be set up in case of partition.

The Indian political leaders accepted the Plan on 2 June. It did not deal with the question of the princely states, but on 3 June Mountbatten advised them against remaining independent and urged them to join one of the two new dominions.[42]

The Muslim League's demands for a separate state were thus conceded. The Congress' position on unity was also taken into account while making Pakistan as small as possible. Mountbatten's formula was to divide India and at the same time retain maximum possible unity.

Within British India, the border between India and Pakistan (the Radcliffe Line) was determined by a British Government-commissioned report prepared under the chairmanship of a London barrister, Sir Cyril Radcliffe. Pakistan came into being with two non-contiguous enclaves, East Pakistan (today Bangladesh) and West Pakistan, separated geographically by India. India was formed out of the majority Hindu regions of British India, and Pakistan from the majority Muslim areas.

On 18 July 1947, the British Parliament passed the Indian Independence Act that finalized the arrangements for partition and abandoned British suzerainty over the princely states, of which there were several hundred, leaving them free to choose whether to accede to one of the new dominions. The Government of India Act 1935 was adapted to provide a legal framework for the new dominions.

Following its creation as a new country in August 1947, Pakistan applied for membership of the United Nations and was accepted by the General Assembly on 30 September 1947. The Dominion of India continued to have the existing seat as India had been a founding member of the United Nations since 1945.[43]

Radcliffe Line

-

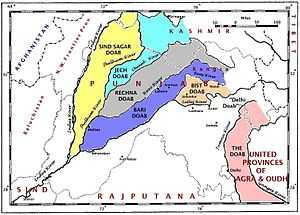

A map of the Punjab region c. 1947.

The Punjab – the region of the five rivers east of Indus: Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej — consists of interfluvial doabs, or tracts of land lying between two confluent rivers. These are the Sind-Sagar doab (between Indus and Jhelum), the Jech doab (Jhelum/Chenab), the Rechna doab (Chenab/Ravi), the Bari doab (Ravi/Beas), and the Bist doab (Beas/Sutlej) (see map). In early 1947, in the months leading up to the deliberations of the Punjab Boundary Commission, the main disputed areas appeared to be in the Bari and Bist doabs, although some areas in the Rechna doab were claimed by the Congress and Sikhs. In the Bari doab, the districts of Gurdaspur, Amritsar, Lahore, and Montgomery (Sahiwal) were all disputed.[44]

All of these disputed districts (other than Amritsar, which was 46.5% Muslim) had Muslim majorities; albeit, in Gurdaspur, the Muslim majority, at 51.1%, was slender. At a smaller area-scale, only three tehsils (sub-units of a district) in the disputed section of the Bari doab had non-Muslim majorities. These were: Pathankot (in the extreme north of Gurdaspur, which was not in dispute), and Amritsar and Tarn Taran in Amritsar district. In addition, there were four Muslim-majority tehsils east of Beas-Sutlej (with two where Muslims outnumbered Hindus and Sikhs together).[44]

Before the Boundary Commission began formal hearings, governments were set up for the East and the West Punjab regions. Their territories were provisionally divided by "notional division" based on simple district majorities. In both the Punjab and Bengal, the Boundary Commission consisted of two Muslim and two non-Muslim judges with Sir Cyril Radcliffe as a common chairman.[44]

The mission of the Punjab commission was worded generally as the following: "To demarcate the boundaries of the two parts of the Punjab, on the basis of ascertaining the contiguous majority areas of Muslims and non-Muslims. In doing so, it will take into account other factors."[44]

Each side (the Muslims and the Congress/Sikhs) presented its claim through counsel with no liberty to bargain. The judges too had no mandate to compromise and on all major issues they "divided two and two, leaving Sir Cyril Radcliffe the invidious task of making the actual decisions."[44]

Independence, population transfer, and violence

Massive population exchanges occurred between the two newly formed states in the months immediately following Partition. "The population of undivided India in 1947 was approx 390 million. After partition, there were 330 million people in India, 30 million in West Pakistan, and 30 million people in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh)." Once the lines were established, about 14.5 million people crossed the borders to what they hoped was the relative safety of religious majority. The 1951 Census of Pakistan identified the number of displaced persons in Pakistan at 7,226,600, presumably all Muslims who had entered Pakistan from India. Similarly, the 1951 Census of India enumerated 7,295,870 displaced persons, apparently all Hindus and Sikhs who had moved to India from Pakistan immediately after the Partition. The two numbers add up to 14.5 million. Since both censuses were held about 3.6 years after the Partition, the enumeration included net population increase after the mass migration.

About 11.2 million ( 77.4% of the displaced persons) were in the west, with the Punjab accounting for most of it: 6.5 million Muslims moved from India to West Pakistan, and 4.7 million Hindus and Sikhs moved from West Pakistan to India; thus the net migration in the west from India to West Pakistan (now Pakistan) was 1.8 million.

The remaining 3.3 million (22.6% of the displaced persons) were in the east: 2.6 million moved from East Pakistan to India and 0.7 million moved from India to East Pakistan (now Bangladesh); thus net migration in the east was 1.9 million into India. The newly formed governments were completely unequipped to deal with migrations of such staggering magnitude, and massive violence and slaughter occurred on both sides of the border. Estimates of the number of deaths vary, with low estimates at 200,000 and high estimates at 1,000,000.[45]

Punjab

The Indian state of East Punjab was created in 1947, when the Partition of India split the former British province of Punjab between India and Pakistan. The mostly Muslim western part of the province became Pakistan's Punjab province; the mostly Sikh and Hindu eastern part became India's East Punjab state. Many Hindus and Sikhs lived in the west, and many Muslims lived in the east, and the fears of all such minorities were so great that the Partition saw many people displaced and much intercommunal violence.

Lahore and Amritsar were at the centre of the problem; the Boundary Commission was not sure where to place them – to make them part of India or Pakistan. The Commission decided to give Lahore to Pakistan, whilst Amritsar became part of India. Some areas in Punjab, including Lahore, Rawalpindi, Multan, and Gujrat, had a large Sikh and Hindu population, and many of the residents were attacked or killed. On the other side, in East Punjab, cities such as Amritsar, Ludhiana, Gurdaspur, and Jalandhar had a majority Muslim population, of which thousands were killed or emigrated.

Bengal

The province of Bengal was divided into the two separate entities of West Bengal belonging to India, and East Bengal belonging to Pakistan. East Bengal was renamed East Pakistan in 1955, and later became the independent nation of Bangladesh after the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971.

While the Muslim majority districts of Murshidabad and Malda were given to India, the Hindu majority district of Khulna and the majority Buddhist, but sparsely populated Chittagong Hill Tracts was given to Pakistan by the award.

Sindh

Hindu Sindhis were expected to stay in Sindh following Partition, as there were good relations between Hindu and Muslim Sindhis. At the time of Partition there were 1,400,000 Hindu Sindhis, though most were concentrated in cities such as Hyderabad, Karachi, Shikarpur, and Sukkur. However, because of an uncertain future in a Muslim country, a sense of better opportunities in India, and most of all a sudden influx of Muslim refugees from Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Rajputana (Rajasthan) and other parts of India, many Sindhi Hindus decided to leave for India.

Problems were further aggravated when incidents of violence instigated by Muslim refugees broke out in Karachi and Hyderabad. According to the 1951 Census of India, nearly 776,000 Sindhi Hindus fled to India.[46] Unlike the Punjabi Hindus and Sikhs, Sindhi Hindus did not have to witness any massive scale rioting; however, their entire province had gone to Pakistan and thus they felt like a homeless community. Despite this migration, a significant Sindhi Hindu population still resides in Pakistan's Sindh province where they number at around 2.28 million as per Pakistan's 1998 census; the Sindhi Hindus in India were at 2.57 million as per India's 2001 Census. Some bordering districts in Sindh were Hindu Majority like Tharparkar District, Umerkot, Mirpurkhas, Sanghar and Badin, but their population is decreasing and they consider themselves a minority in decline. In fact, only Umerkot still has a majority of Hindus in the district.[47]

Resettlement of refugees in India: 1947–1957

Many Sikhs and Hindu Punjabis fled Western Punjab and settled in the Indian parts of Punjab and Delhi. Hindus fleeing from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) settled across Eastern India and Northeastern India, many ending up in neighboring Indian states such as West Bengal, Assam, and Tripura. Some migrants were sent to the Andaman islands where Bengalis today form the largest linguistic group.

Delhi received the largest number of refugees for a single city – the population of Delhi grew rapidly in 1947 from under 1 million (917,939) to a little less than 2 million (1,744,072) during the period 1941–1951.[48] The refugees were housed in various historical and military locations such as the Purana Qila, Red Fort, and military barracks in Kingsway Camp (around the present Delhi University). The latter became the site of one of the largest refugee camps in northern India with more than 35,000 refugees at any given time besides Kurukshetra camp near Panipat. The camp sites were later converted into permanent housing through extensive building projects undertaken by the Government of India from 1948 onwards. A number of housing colonies in Delhi came up around this period like Lajpat Nagar, Rajinder Nagar, Nizamuddin East, Punjabi Bagh, Rehgar Pura, Jangpura and Kingsway Camp. A number of schemes such as the provision of education, employment opportunities, and easy loans to start businesses were provided for the refugees at the all-India level.[49]

Resettlement of refugees in Pakistan: 1947–1957

In the aftermath of partition, a huge population exchange occurred between the two newly formed states. About 14.5 million people crossed the borders, including 7,226,000 Muslims who came to Pakistan from India while 7,295,000 Hindus and Sikhs moved to India from Pakistan. Of the 6.5 million Muslims that came to West Pakistan (now Pakistan), about 5.3 million settled in Punjab, Pakistan and around 1.2 million settled in Sindh. The other 0.7 million Muslims went to East Pakistan (now Bangladesh).

Most of those migrants who settled in Punjab, Pakistan came from the neighbouring Indian regions of Punjab, Haryana and Himachal Pradesh while others were from Jammu and Kashmir and Rajasthan. On the other hand, most of those migrants who arrived in Sindh were primarily of Urdu-speaking background (termed the Muhajir people) and came from the northern and central urban centres of India, such as Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat and Rajasthan via the Wahgah and Munabao borders; however a limited number of Muhajirs also arrived by air and on ships. People who wished to go to India from all over Sindh awaited their departure to India by ship at the Swaminarayan temple in Karachi and were visited by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan.[50]

Later in 1950s, the majority of Urdu speaking refugees who migrated after the independence were settled in the port city of Karachi in southern Sindh and in the metropolitan cities of Hyderabad, Sukkur, Nawabshah and Mirpurkhas. In addition, some Urdu-speakers settled in the cities of Punjab, mainly in Lahore, Multan, Bahawalpur and Rawalpindi. The number of migrants in Sindh was placed at over 1,167,000 of whom 617,000 went to Karachi alone. Karachi grew from a population of around 400,000 in 1947 into more than 1.3 million in 1953.

Rehabilitation of women

Both sides promised each other that they would try to restore women abducted during the riots. The Indian government claimed that 33,000 Hindu and Sikh women were abducted, and the Pakistani government claimed that 50,000 Muslim women were abducted during riots. By 1949, there were governmental claims that 12,000 women had been recovered in India and 6,000 in Pakistan.[51] By 1954 there were 20,728 recovered Muslim women and 9,032 Hindu and Sikh women recovered from Pakistan.[52] Most of the Hindu and Sikh women refused to go back to India fearing that they would never be accepted by their family, a fear mirrored by Muslim women. [53]

Perspectives

The Partition was a highly controversial arrangement, and remains a cause of much tension on the Indian subcontinent today. The British Viceroy, Lord Mountbatten of Burma has not only been accused of rushing the process through, but also is alleged to have influenced the Radcliffe Line in India's favour.[54][55] The commission took longer to decide on a final boundary than on the partition itself. Thus the two nations were granted their independence even before there was a defined boundary between them.

Some critics allege that British haste led to increased cruelties during the Partition.[56] Because independence was declared prior to the actual Partition, it was up to the new governments of India and Pakistan to keep public order. No large population movements were contemplated; the plan called for safeguards for minorities on both sides of the new border. It was a task at which both states failed. There was a complete breakdown of law and order; many died in riots, massacre, or just from the hardships of their flight to safety. What ensued was one of the largest population movements in recorded history. According to Richard Symonds: At the lowest estimate, half a million people perished and twelve million became homeless.[57]

However, many argue that the British were forced to expedite the Partition by events on the ground.[58] Once in office, Mountbatten quickly became aware if Britain were to avoid involvement in a civil war, which seemed increasingly likely, there was no alternative to partition and a hasty exit from India.[58] Law and order had broken down many times before Partition, with much bloodshed on both sides. A massive civil war was looming by the time Mountbatten became Viceroy. After the Second World War, Britain had limited resources,[59] perhaps insufficient to the task of keeping order. Another viewpoint is that while Mountbatten may have been too hasty he had no real options left and achieved the best he could under difficult circumstances.[60] The historian Lawrence James concurs that in 1947 Mountbatten was left with no option but to cut and run. The alternative seemed to be involvement in a potentially bloody civil war from which it would be difficult to get out.[61]

Conservative elements in England consider the partition of India to be the moment that the British Empire ceased to be a world power, following Curzon's dictum: "the loss of India would mean that Britain drop straight away to a third rate power."[62]

A cross border student initiative, The History Project was launched in 2014 in order to explore the differences in perception of the events during the British era which lead to the partition. The project resulted in a book, that explains both interpretations of the shared history in Pakistan and India.[63][64]

Artistic depictions of the Partition

The partition of India and the associated bloody riots inspired many in India and Pakistan to create literary/cinematic depictions of this event.[65] While some creations depicted the massacres during the refugee migration, others concentrated on the aftermath of the partition in terms of difficulties faced by the refugees in both side of the border. Even now, more than 60 years after the partition, works of fiction and films are made that relate to the events of partition. The early members of the Progressive Artist's Group of Bombay cite "The Partition" of India and Pakistan as a key reason for its founding in December 1947. They included FN Souza, MF Husain, SH Raza, SK Bakre, HA Gade and KH Ara went on to become some of the most important and influential Indian artists of the 20th Century.[66]

Literature describing the human cost of independence and partition comprises Bal K. Gupta's memoirs Forgotten Atrocities (2012), Khushwant Singh's Train to Pakistan (1956), several short stories such as Toba Tek Singh (1955) by Saadat Hassan Manto, Urdu poems such as Subh-e-Azadi (Freedom's Dawn, 1947) by Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Bhisham Sahni's Tamas (1974), Manohar Malgonkar's A Bend in the Ganges (1965), and Bapsi Sidhwa's Ice-Candy Man (1988), among others.[67][68] Salman Rushdie's novel Midnight's Children (1980), which won the Booker Prize and the Booker of Bookers, weaved its narrative based on the children born with magical abilities on midnight of 14 August 1947.[68] Freedom at Midnight (1975) is a non-fiction work by Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre that chronicled the events surrounding the first Independence Day celebrations in 1947.

There is a paucity of films related to the independence and partition.[69][70][71] Early films relating to the circumstances of the independence, partition and the aftermath include Nemai Ghosh's Chinnamul (Bengali) (1950),[69] Dharmputra (1961)[72] Lahore (1948), Chhalia (1956), Nastik (1953). Ritwik Ghatak's Meghe Dhaka Tara (Bengali) (1960), Komal Gandhar (Bengali) (1961), Subarnarekha (Bengali) (1962);[69][73] later films include Garm Hava (1973) and Tamas (1987).[72] From the late 1990s onwards, more films on this theme were made, including several mainstream ones, such as Earth (1998), Train to Pakistan (1998) (based on the aforementined book), Hey Ram (2000), Gadar: Ek Prem Katha (2001), Khamosh Pani (2003), Pinjar (2003), Partition (2007) and Madrasapattinam (2010).[72] The biographical films Gandhi (1982), Jinnah (1998) and Sardar (1993) also feature independence and partition as significant events in their screenplay. A Pakistani drama Daastan, based on the novel Bano, tells the tale of Muslim girls during partition.

The novel Lost Generations (2013) by Manjit Sachdeva describes March 1947 massacre in rural areas of Rawalpindi by Muslim League, followed by massacres on both sides of the new border in August 1947 seen through the eyes of an escaping Sikh family, their settlement and partial rehabilitation in Delhi, and ending in ruin (including death), for the second time in 1984, at the hands of mobs after a Sikh assassinated the prime minister.

The 2013 Google India advertisement Reunion (about the Partition of India) has had a strong impact in India and Pakistan, leading to hope for the easing of travel restrictions between the two countries.[74][75][76] It went viral[77][78] and was viewed more than 1.6 million times before officially debuting on television on 15 November 2013.[79]

See also

- List of princely states of India

- Indian independence movement

- Pakistan Movement

- History of Bangladesh

- History of India

- History of Pakistan

- Indo-Pakistani War of 1947

- Indian annexation of Goa

Notes

- ↑ Khan 2007, p. 1.

- ↑ Paul R. Brass (2003). "The partition of India and retributive genocide in the Punjab, 1946–47: means, methods, and purposes" (PDF). Journal of Genocide Research. p. 75 (5(1), 71–101). Retrieved 2014-08-16.

- ↑ "20th-century international relations (politics) :: South Asia". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2014-08-16.

- ↑ "Rupture in South Asia" (PDF). UNHCR. Retrieved 2014-08-16.

- ↑ Dr Crispin Bates (2011-03-03). "The Hidden Story of Partition and its Legacies". BBC. Retrieved 2014-08-16.

- ↑ Tanya Basu (15 August 2014). "The Fading Memory of South Asia's Partition". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2014-08-16.

- ↑ Sword For Pen, Time, 12 April 1937

- ↑ "Nepal." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. "Bhutan."

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 (Spear 1990, p. 176)

- ↑ (Spear 1990, p. 176), (Stein 2001, p. 291), (Ludden 2002, p. 193), (Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, p. 156)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 (Bandyopadhyay 2005, p. 260)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 (Ludden 2002, p. 193)

- ↑ (Ludden 2002, p. 199)

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 (Ludden 2002, p. 200)

- ↑ (Stein 2001, p. 286)

- ↑ Talbot & Singh 2009, p. 20.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 (Ludden 2002, p. 201)

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Brown 1994, pp. 197–198

- ↑ Olympic Games Antwerp 1920: Official Report, Nombre de bations representees, p. 168. Quote: "31 Nations avaient accepté l'invitation du Comité Olympique Belge: ... la Grèce – la Hollande Les Indes Anglaises – l'Italie – le Japon ..."

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Brown 1994, pp. 200–201

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 21.6 21.7 21.8 Brown 1994, pp. 205–207

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Talbot & Singh 2009, p. 31.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 23.6 23.7 23.8 23.9 23.10 Talbot & Singh 2009, p. 32.

- ↑ Talbot & Singh 2009, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 25.5 25.6 Talbot & Singh 2009, p. 33.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 Talbot & Singh 2009, p. 34.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Khan 2007, p. 18.

- ↑ Talbot & Singh 2009, pp. 34–35.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Talbot & Singh 2009, p. 35.

- ↑ Stein & Arnold 2010, p. 289: Quote: "Gandhi was the leading genius of the later, and ultimately successful, campaign for India's independence"

- ↑ Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, p. 209.

- ↑ Khan 2007, p. 43.

- ↑ (Robb 2002, p. 190)

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 (Judd 2004, pp. 172–173)

- ↑ (Judd 2004, pp. 170–171)

- ↑ (Judd 2004, p. 172)

- ↑ Khan 2007, pp. 64–65.

- ↑ Talbot & Singh 2009, p. 69: Quote: "Despite the Muslim League's denials, the outbreak was clearly linked with the celebration of Direction Action Day. Muslim processionists who had gone to the staging ground of the 150-feet-high Ochterlony Monument on the maidan to hear the Muslim League Prime Minister Suhrawardy, attacked Hindus on their way back. They were heard shouting slogans as 'Larke Lenge Pakistan' (We shall win Pakistan by force). Violence spread to North Calcutta when Muslim crowds tried to force Hindu shopkeepers to observe the day's strike (hartal) call. The circulation of pamphlets in advance of Direct Action Day made a clear connection with the use of violence and the demand for Pakistan."

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Talbot & Singh 2009, p. 67: Quote: "The signs of 'ethnic cleansing' are first evident in the Great Calcutta Killing of 16–19 August 1946."

- ↑ Talbot & Singh 2009, p. 68.

- ↑ Talbot & Singh 2009, pp. 67–68.

- ↑ Sankar Ghose, Jawaharlal Nehru, a biography (1993), p. 181

- ↑ Thomas R. G. C., 'Nations, States, and Secession: Lessons from the Former Yugoslavia', in Mediterranean Quarterly, Volume 5 Number 4 (Duke University Press, Fall 1994), pp. 40–65

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 44.4 (Spate 1947, pp. 126–137)

- ↑ Death toll in the partition. Users.erols.com.

- ↑ Markovits, Claude (2000). The Global World of Indian Merchants, 1750–1947. Cambridge University Press. p. 278. ISBN 0-521-62285-9.

- ↑ "Population of Hindus in the World". Pakistan Hindu Council.

- ↑ Census of India, 1941 and 1951.

- ↑ Kaur, Ravinder (2007). Since 1947: Partition Narratives among Punjabi Migrants of Delhi. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-568377-6.

- ↑ Vazira Fazila-Yacoobali Zamindar (2007). The long partition and the making of modern South Asia. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231138468. Retrieved 22 May 2009. Page 52

- ↑ Perspectives on Modern South Asia: A Reader in Culture, History, and ... – Kamala Visweswara. nGoogle Books.in (16 May 2011).

- ↑ Borders & boundaries: women in India's partition – Ritu Menon, Kamla Bhasi. nGoogle Books.in (24 April 1993).

- ↑ Jayawardena, Kumari; de Alwi, Malathi (1996). Embodied violence: Communalising women's sexuality in South Asia. Zed Books. ISBN 9781856494489.

- ↑ K. Z. Islam, 2002, The Punjab Boundary Award, Inretrospect

- ↑ Partitioning India over lunch, Memoirs of a British civil servant Christopher Beaumont. BBC News (10 August 2007).

- ↑ Stanley Wolpert, 2006, Shameful Flight: The Last Years of the British Empire in India, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-515198-4

- ↑ Richard Symonds, 1950, The Making of Pakistan, London, OCLC 245793264, p 74

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Lawrence J. Butler, 2002, Britain and Empire: Adjusting to a Post-Imperial World, p. 72

- ↑ Lawrence J. Butler, 2002, Britain and Empire: Adjusting to a Post-Imperial World, p 72

- ↑ Ronald Hyam, Britain's Declining Empire: The Road to Decolonisation, 1918–1968, page 113; Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-86649-9, 2007

- ↑ Lawrence James, Rise and Fall of the British Empire

- ↑ Judd, Dennis, The Lion and the Tiger: The rise and Fall of the British Raj,1600–1947. Oxford University Press: New York. (2010) p. 138.

- ↑ One history, two narratives, Beena Sarwar, The News

- ↑ http://thehistory-project.org/

- ↑ Cleary, Joseph N. (3 January 2002). Literature, Partition and the Nation-State: Culture and Conflict in Ireland, Israel and Palestine. Cambridge University Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-521-65732-7. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

The partition of India figures in a goo deal of imaginative writing...

- ↑ http://www.artnewsnviews.com/view-article.php?article=progressive-artists-group-of-bombay-an-overview&iid=29&articleid=800

- ↑ Bhatia, Nandi (1996). "Twentieth Century Hindi Literature". In Natarajan, Nalini. Handbook of Twentieth-Century Literatures of India. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 146–147. ISBN 978-0-313-28778-7. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Roy, Rituparna (15 July 2011). South Asian Partition Fiction in English: From Khushwant Singh to Amitav Ghosh. Amsterdam University Press. pp. 24–29. ISBN 978-90-8964-245-5. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 69.2 Mandal, Somdatta (2008). "Constructing Post-partition Bengali Cultural Identity through Films". In Bhatia, Nandi; Roy, Anjali Gera. Partitioned Lives: Narratives of Home, Displacement, and Resettlement. Pearson Education India. pp. 66–69. ISBN 978-81-317-1416-4. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ↑ Dwyer, R. (2010). "Bollywood's India: Hindi Cinema as a Guide to Modern India". Asian Affairs 41 (3): 381–398. doi:10.1080/03068374.2010.508231. (subscription required)

- ↑ Sarkar, Bhaskar (29 April 2009). Mourning the Nation: Indian Cinema in the Wake of Partition. Duke University Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-8223-4411-7. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 72.2 Vishwanath, Gita; Malik, Salma (2009). "Revisiting 1947 through Popular Cinema: a Comparative Study of India and Pakistan" (PDF). Economic and Political Weekly XLIV (36): 61–69. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ↑ Raychaudhuri, Anindya (2009). "Resisting the Resistible: Re-writing Myths of Partition in the Works of Ritwik Ghatak". Social Semiotics 19 (4): 469–481. doi:10.1080/10350330903361158.(subscription required)

- ↑ Naqvi, Sibtain (19 November 2013). "Google can envision Pakistan-India harmony in less than 4 minutes…can we?". The Express Tribune.

- ↑ PTI (15 November 2013). "Google reunion ad reignites hope for easier Indo-Pak visas". Deccan Chronicle.

- ↑ Chatterjee, Rhitu (20 November 2013). "This ad from Google India brought me to tears". Public Radio International,.

- ↑ Peter, Sunny (15 November 2013). "Google Search: Reunion Video Touches Emotions in India, Pakistan; Goes Viral [Watch VIDEO]". International Business Times.

- ↑ "Google's India-Pak reunion ad strikes emotional chord". The Times of India. 14 November 2013.

- ↑ Johnson, Kay (15 November 2013). "Google ad an unlikely hit in both India, Pakistan by referring to traumatic 1947 partition". ABC News/Associated Press.

Further reading

- Textbook histories

- Bandyopādhyāẏa, Śekhara (2004). From Plassey to partition: a history of modern India. Delhi: Orient Blackswan. ISBN 978-81-250-2596-2. Retrieved 5 November 2011

- Bose, Sugata; Jalal, Ayesha (2004). Modern South Asia: History, Culture, Political economy: second edition. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-39715-0. Retrieved 5 November 2011

- Brown, Judith Margaret (1994). Modern India: the origins of an Asian democracy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-873112-2. Retrieved 5 November 2011

- Ayub, Muhammad (2005). An army, Its Role and Rule: A History of the Pakistan Army from Independence to Kargil, 1947–1999. RoseDog Books. ISBN 9780805995947.

- Judd, Denis (2010). The lion and the tiger: the rise and fall of the British Raj, 1600–1947. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280579-9. Retrieved 5 November 2011

- Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2004). A history of India. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-32920-0. Retrieved 5 November 2011

- Ludden, David (2002). India and South Asia: a short history. Oneworld. ISBN 978-1-85168-237-9. Retrieved 5 November 2011

- Markovits, Claude (2004). A history of modern India, 1480–1950. Anthem Press. ISBN 978-1-84331-152-2. Retrieved 5 November 2011

- Metcalf, Barbara Daly; Metcalf, Thomas R. (2006). A concise history of modern India. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86362-9. Retrieved 5 November 2011

- Peers, Douglas M. (2006). India under colonial rule: 1700–1885. Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0-582-31738-3. Retrieved 5 November 2011

- Robb, Peter (2011). A History of India. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-34549-2. Retrieved 5 November 2011

- Spear, Percival (1990). A history of India, Volume 2. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-013836-8. Retrieved 5 November 2011

- Stein, Burton; Arnold, David (2010). A History of India. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-9509-6. Retrieved 5 November 2011

- Wolpert, Stanley (2008). A new history of India. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533756-3. Retrieved 5 November 2011

- Monographs

- Ishtiaq Ahmed, Ahmed, Ishtiaq. 2011. The Punjab Bloodied, Partitioned and Cleansed: Unravelling the 1947 Tragedy through Secret British Reports and First Person Account. New Delhi: RUPA Publications. 808 pages. ISBN 978-81-291-1862-2

- Ansari, Sarah. 2005. Life after Partition: Migration, Community and Strife in Sindh: 1947—1962. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. 256 pages. ISBN 0-19-597834-X.

- Butalia, Urvashi. 1998. The Other Side of Silence: Voices from the Partition of India. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. 308 pages. ISBN 0-8223-2494-6

- Butler, Lawrence J. 2002. Britain and Empire: Adjusting to a Post-Imperial World. London: I.B.Tauris. 256 pages. ISBN 1-86064-449-X

- Chakrabarty; Bidyut. 2004. The Partition of Bengal and Assam: Contour of Freedom (RoutledgeCurzon, 2004) online edition

- Chatterji, Joya. 2002. Bengal Divided: Hindu Communalism and Partition, 1932—1947. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. 323 pages. ISBN 0-521-52328-1.

- Chester, Lucy P. 2009. Borders and Conflict in South Asia: The Radcliffe Boundary Commission and the Partition of Punjab. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-7899-6.

- Daiya, Kavita. 2008. Violent Belongings: Partition, Gender, and National Culture in Postcolonial India. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. 274 pages. ISBN 978-1-59213-744-2.

- Gilmartin, David. 1988. Empire and Islam: Punjab and the Making of Pakistan. Berkeley: University of California Press. 258 pages. ISBN 0-520-06249-3.

- Gossman, Partricia. 1999. Riots and Victims: Violence and the Construction of Communal Identity Among Bengali Muslims, 1905–1947. Westview Press. 224 pages. ISBN 0-8133-3625-2

- Gupta, Bal K. 2012 "Forgotten Atrocities: Memoirs of a Survivor of 1947 Partition of India". lulu.com

- Hansen, Anders Bjørn. 2004. "Partition and Genocide: Manifestation of Violence in Punjab 1937–1947", India Research Press. ISBN 978-81-87943-25-9.

- Harris, Kenneth. Attlee (1982) pp 355–87

- Hasan, Mushirul (2001). India's Partition: Process, Strategy and Mobilization. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 444 pages. ISBN 0-19-563504-3.

- Herman, Arthur. Gandhi & Churchill: The Epic Rivalry that Destroyed an Empire and Forged Our Age (2009)

- Ikram, S. M. 1995. Indian Muslims and Partition of India. Delhi: Atlantic. ISBN 81-7156-374-0

- Jain, Jasbir (2007). Reading Partition, Living Partition. Rawat Publications, 338 pages. ISBN 81-316-0045-9

- Jalal, Ayesha (1993). The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League and the Demand for Pakistan. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 334 pages. ISBN 0-521-45850-1

- Kaur, Ravinder. 2007. "Since 1947: Partition Narratives among Punjabi Migrants of Delhi". Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-568377-6.

- Khan, Yasmin (2007). The Great Partition: The Making of India and Pakistan. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12078-3. Retrieved 2 October 2013

- Khosla, G. D. Stern reckoning : a survey of the events leading up to and following the partition of India New Delhi: Oxford University Press:358 pages Published: February 1990 ISBN 0-19-562417-3

- Lamb, Alastair (1991). Kashmir: A Disputed Legacy, 1846–1990. Roxford Books. ISBN 0-907129-06-4

- Metcalf, Barbara; Metcalf, Thomas R. (2006). A Concise History of Modern India (Cambridge Concise Histories). Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. Pp. xxxiii, 372. ISBN 0-521-68225-8

- Moon, Penderel. (1999). The British Conquest and Dominion of India (2 vol. 1256pp)

- Moore, R.J. (1983). Escape from Empire: The Attlee Government and the Indian Problem, the standard history of the British position

- Nair, Neeti. (2010) Changing Homelands: Hindu Politics and the Partition of India

- Page, David, Anita Inder Singh, Penderel Moon, G. D. Khosla, and Mushirul Hasan. 2001. The Partition Omnibus: Prelude to Partition/the Origins of the Partition of India 1936-1947/Divide and Quit/Stern Reckoning. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-565850-7

- Pal, Anadish Kumar. 2010. World Guide to the Partition of INDIA. Kindle Edition: Amazon Digital Services. 282 KB. ASIN B0036OSCAC

- Pandey, Gyanendra. 2002. Remembering Partition:: Violence, Nationalism and History in India. Cambridge University Press. 232 pages. ISBN 0-521-00250-8 online edition

- Panigrahi; D.N. 2004. India's Partition: The Story of Imperialism in Retreat London: Routledge. online edition

- Raja, Masood Ashraf. Constructing Pakistan: Foundational Texts and the Rise of Muslim National Identity, 1857–1947, Oxford 2010, ISBN 978-0-19-547811-2

- Raza, Hashim S. 1989. Mountbatten and the partition of India. New Delhi: Atlantic. ISBN 81-7156-059-8

- Shaikh, Farzana. 1989. Community and Consensus in Islam: Muslim Representation in Colonial India, 1860—1947. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 272 pages. ISBN 0-521-36328-4.

- Singh, Jaswant. (2011) Jinnah: India, Partition, Independence

- Talbot, Ian and Gurharpal Singh (eds). 1999. Region and Partition: Bengal, Punjab and the Partition of the Subcontinent. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. 420 pages. ISBN 0-19-579051-0.

- Talbot, Ian. 2002. Khizr Tiwana: The Punjab Unionist Party and the Partition of India. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. 216 pages. ISBN 0-19-579551-2.

- Talbot, Ian. 2006. Divided Cities: Partition and Its Aftermath in Lahore and Amritsar. Oxford and Karachi: Oxford University Press. 350 pages. ISBN 0-19-547226-8.

- Wolpert, Stanley. 2006. Shameful Flight: The Last Years of the British Empire in India. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. 272 pages. ISBN 0-19-515198-4.

- Talbot, Ian; Singh, Gurharpal (2009). The Partition of India. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85661-4. Retrieved 2 October 2013

- Wolpert, Stanley. 1984. Jinnah of Pakistan

- Articles

- Brass, Paul. 2003. The partition of India and retributive genocide in the Punjab,1946–47: means, methods, and purposes Washington University

- Gilmartin, David. 1998. "Partition, Pakistan, and South Asian History: In Search of a Narrative." The Journal of Asian Studies, 57(4):1068–1095.

- Gupta, Bal K. "Death of Mahatma Gandhi and Alibeg Prisoners" www.dailyexcelsior.com

- Gupta, Bal K. "Train from Pakistan" www.nripulse.com

- Gupta, Bal K. "November 25, 1947, Pakisatni Invasion of Mirpur". www.dailyexcelsior.com

- Jeffrey, Robin. 1974. "The Punjab Boundary Force and the Problem of Order, August 1947" – Modern Asian Studies 8(4):491–520.

- Kaur, Ravinder. 2009. Citizenship: Refugees, Subjects and Postcolonial State in India's Partition', Cultural and Social History.

- Kaur, Ravinder. 2008. 'Narrative Absence: An 'untouchable' account of India's Partition Migration, Contributions to Indian Sociology.

- Kaur Ravinder. 2007. "India and Pakistan: Partition Lessons". Open Democracy.

- Kaur, Ravinder. 2006. "The Last Journey: Social Class in the Partition of India". Economic and Political Weekly, June 2006. epw.org.in

- Khan, Lal (2003). Partition – Can it be undone?. Wellred Publications. p. 228. ISBN 1-900007-15-0.

- Mookerjea-Leonard, Debali. 2005. "Divided Homelands, Hostile Homes: Partition, Women and Homelessness". Journal of Commonwealth Literature, 40(2):141–154.

- Mookerjea-Leonard, Debali. 2004. "Quarantined: Women and the Partition". Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, 24(1): 35–50.

- Morris-Jones. 1983. "Thirty-Six Years Later: The Mixed Legacies of Mountbatten's Transfer of Power". International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs), 59(4):621–628.

- Noorani, A. G. (22 Dec 2001 – 4 Jan 2002). "The Partition of India". Frontline 18 (26). Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- Spate, O. H. K. (1947). "The Partition of the Punjab and of Bengal". The Geographical Journal 110 (4/6): 201–218. doi:10.2307/1789950

- Spear, Percival. 1958. "Britain's Transfer of Power in India." Pacific Affairs, 31(2):173–180.

- Talbot, Ian. 1994. "Planning for Pakistan: The Planning Committee of the All-India Muslim League, 1943–46". Modern Asian Studies, 28(4):875–889.

Visaria, Pravin M. 1969. "Migration Between India and Pakistan, 1951–61" Demography, 6(3):323–334.

- Chopra, R. M., "The Punjab And Bengal", Calcutta, 1999.

- Primary sources

- Mansergh, Nicholas, and Penderel Moon, eds. The Transfer of Power 1942–47 (12 vol., London: HMSO . 1970–83) comprehensive collection of British official and private documents

- Moon, Penderel. (1998) Divide & Quit

- Popularizations

- Collins, Larry and Dominique Lapierre: Freedom at Midnight. London: Collins, 1975. ISBN 0-00-638851-5

- Zubrzycki, John. (2006) The Last Nizam: An Indian Prince in the Australian Outback. Pan Macmillan, Australia. ISBN 978-0-330-42321-2.

- Memoirs and oral history

- Bonney, Richard; Hyde, Colin; Martin, John. "Legacy of Partition, 1947–2009: Creating New Archives from the Memories of Leicestershire People," Midland History, (Sept 2011), Vol. 36 Issue 2, pp 215–224

- Azad, Maulana Abul Kalam: India Wins Freedom, Orient Longman, 1988. ISBN 81-250-0514-5

- Mountbatten, Pamela. (2009) India Remembered: A Personal Account of the Mountbattens During the Transfer of Power

- Historical-Fiction

- Mohammed, Javed: Walk to Freedom, Rumi Bookstore, 2006. ISBN 978-0-9701261-2-2

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Partition of British India. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Partition of India. |

- The Indian Subcontinent Partition Documentation (ISPaD) Project

- The Indian Subcontinent Partition Documentation (ISPaD) Project - YouTube

- 1947 Partition Archive

- 1947 Partition Archive - YouTube

- India Memory Project - 1947 India Pakistan Partition

- The Road to Partition 1939-1947 - The National Archives

- Bibliographies

- Select Research Bibliography on the Partition of India, Compiled by Vinay Lal, Department of History, UCLA; University of California at Los Angeles

- A select list of Indian Publications on the Partition of India (Punjab & Bengal); University of Virginia

- South Asian History: Colonial India — University of California, Berkeley Collection of documents on colonial India, Independence, and Partition

- Indian Nationalism — Fordham University archive of relevant public-domain documents

- Other links

- Clip from 1947 newsreel showing Indian independence ceremony

- Through My Eyes Website Imperial War Museum – Online Exhibition (including images, video and interviews with refugees from the Partition of India)

- A People Partitioned Five radio programmes broadcast on the BBC World Service in 1997 containing the voices of people across South Asia who lived through Partition.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||