Partition function (mathematics)

The partition function or configuration integral, as used in probability theory, information theory and dynamical systems, is a generalization of the definition of a partition function in statistical mechanics. It is a special case of a normalizing constant in probability theory, for the Boltzmann distribution. The partition function occurs in many problems of probability theory because, in situations where there is a natural symmetry, its associated probability measure, the Gibbs measure, has the Markov property. This means that the partition function occurs not only in physical systems with translation symmetry, but also in such varied settings as neural networks (the Hopfield network), and applications such as genomics, corpus linguistics and artificial intelligence, which employ Markov networks, and Markov logic networks. The Gibbs measure is also the unique measure that has the property of maximizing the entropy for a fixed expectation value of the energy; this underlies the appearance of the partition function in maximum entropy methods and the algorithms derived therefrom.

The partition function ties together many different concepts, and thus offers a general framework in which many different kinds of quantities may be calculated. In particular, it shows how to calculate expectation values and Green's functions, forming a bridge to Fredholm theory. It also provides a natural setting for the information geometry approach to information theory, where the Fisher information metric can be understood to be a correlation function derived from the partition function; it happens to define a Riemannian manifold.

When the setting for random variables is on complex projective space or projective Hilbert space, geometrized with the Fubini–Study metric, the theory of quantum mechanics and more generally quantum field theory results. In these theories, the partition function is heavily exploited in the path integral formulation, with great success, leading to many formulas nearly identical to those reviewed here. However, because the underlying measure space is complex-valued, as opposed to the real-valued simplex of probability theory, an extra factor of i appears in many formulas. Tracking this factor is troublesome, and is not done here. This article focuses primarily on classical probability theory, where the sum of probabilities total to one.

Definition

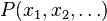

Given a set of random variables  taking on values

taking on values  , and some sort of potential function or Hamiltonian

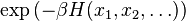

, and some sort of potential function or Hamiltonian  , the partition function is defined as

, the partition function is defined as

The function H is understood to be a real-valued function on the space of states  , while

, while  is a real-valued free parameter (conventionally, the inverse temperature). The sum over the

is a real-valued free parameter (conventionally, the inverse temperature). The sum over the  is understood to be a sum over all possible values that each of the random variables

is understood to be a sum over all possible values that each of the random variables  may take. Thus, the sum is to be replaced by an integral when the

may take. Thus, the sum is to be replaced by an integral when the  are continuous, rather than discrete. Thus, one writes

are continuous, rather than discrete. Thus, one writes

for the case of continuously-varying  .

.

When H is an observable, such as a finite-dimensional matrix or an infinite-dimensional Hilbert space operator or element of a C-star algebra, it is common to express the summation as a trace, so that

When H is infinite-dimensional, then, for the above notation to be valid, the argument must be trace class, that is, of a form such that the summation exists and is bounded.

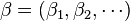

The number of variables  need not be countable, in which case the sums are to be replaced by functional integrals. Although there are many notations for functional integrals, a common one would be

need not be countable, in which case the sums are to be replaced by functional integrals. Although there are many notations for functional integrals, a common one would be

Such is the case for the partition function in quantum field theory.

A common, useful modification to the partition function is to introduce auxiliary functions. This allows, for example, the partition function to be used as a generating function for correlation functions. This is discussed in greater detail below.

The parameter β

The role or meaning of the parameter  can be understood in a variety of different ways. In classical thermodynamics, it is an inverse temperature. More generally, one would say that it is the variable that is conjugate to some (arbitrary) function

can be understood in a variety of different ways. In classical thermodynamics, it is an inverse temperature. More generally, one would say that it is the variable that is conjugate to some (arbitrary) function  of the random variables

of the random variables  . The word conjugate here is used in the sense of conjugate generalized coordinates in Lagrangian mechanics, thus, properly

. The word conjugate here is used in the sense of conjugate generalized coordinates in Lagrangian mechanics, thus, properly  is a Lagrange multiplier. It is not uncommonly called the generalized force. All of these concepts have in common the idea that one value is meant to be kept fixed, as others, interconnected in some complicated way, are allowed to vary. In the current case, the value to be kept fixed is the expectation value of

is a Lagrange multiplier. It is not uncommonly called the generalized force. All of these concepts have in common the idea that one value is meant to be kept fixed, as others, interconnected in some complicated way, are allowed to vary. In the current case, the value to be kept fixed is the expectation value of  , even as many different probability distributions can give rise to exactly this same (fixed) value.

, even as many different probability distributions can give rise to exactly this same (fixed) value.

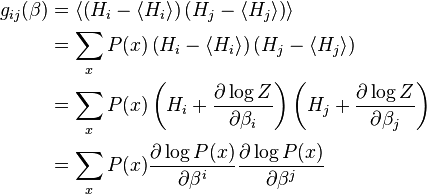

For the general case, one considers a set of functions  that each depend on the random variables

that each depend on the random variables  . These functions are chosen because one wants to hold their expectation values constant, for one reason or another. To constrain the expectation values in this way, one applies the method of Lagrange multipliers. In the general case, maximum entropy methods illustrate the manner in which this is done.

. These functions are chosen because one wants to hold their expectation values constant, for one reason or another. To constrain the expectation values in this way, one applies the method of Lagrange multipliers. In the general case, maximum entropy methods illustrate the manner in which this is done.

Some specific examples are in order. In basic thermodynamics problems, when using the canonical ensemble, the use of just one parameter  reflects the fact that there is only one expectation value that must be held constant: the free energy (due to conservation of energy). For chemistry problems involving chemical reactions, the grand canonical ensemble provides the appropriate foundation, and there are two Lagrange multipliers. One is to hold the energy constant, and another, the fugacity, is to hold the particle count constant (as chemical reactions involve the recombination of a fixed number of atoms).

reflects the fact that there is only one expectation value that must be held constant: the free energy (due to conservation of energy). For chemistry problems involving chemical reactions, the grand canonical ensemble provides the appropriate foundation, and there are two Lagrange multipliers. One is to hold the energy constant, and another, the fugacity, is to hold the particle count constant (as chemical reactions involve the recombination of a fixed number of atoms).

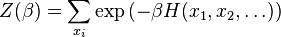

For the general case, one has

with  a point in a space.

a point in a space.

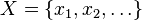

For a collection of observables  , one would write

, one would write

As before, it is presumed that the argument of tr is trace class.

The corresponding Gibbs measure then provides a probability distribution such that the expectation value of each  is a fixed value. More precisely, one has

is a fixed value. More precisely, one has

with the angle brackets  denoting the expected value of

denoting the expected value of  , and

, and ![\mathrm{E}[\;]](../I/m/00e7404bb29bf5d8f3bb4aab76319906.png) being a common alternative notation. A precise definition of this expectation value is given below.

being a common alternative notation. A precise definition of this expectation value is given below.

Although the value of  is commonly taken to be real, it need not be, in general; this is discussed in the section Normalization below. The values of

is commonly taken to be real, it need not be, in general; this is discussed in the section Normalization below. The values of  can be understood to be the coordinates of points in a space; this space is in fact a manifold, as sketched below. The study of these spaces as manifolds constitutes the field of information geometry.

can be understood to be the coordinates of points in a space; this space is in fact a manifold, as sketched below. The study of these spaces as manifolds constitutes the field of information geometry.

Symmetry

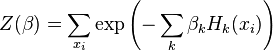

The potential function itself commonly takes the form of a sum:

where the sum over s is a sum over some subset of the power set P(X) of the set  . For example, in statistical mechanics, such as the Ising model, the sum is over pairs of nearest neighbors. In probability theory, such as Markov networks, the sum might be over the cliques of a graph; so, for the Ising model and other lattice models, the maximal cliques are edges.

. For example, in statistical mechanics, such as the Ising model, the sum is over pairs of nearest neighbors. In probability theory, such as Markov networks, the sum might be over the cliques of a graph; so, for the Ising model and other lattice models, the maximal cliques are edges.

The fact that the potential function can be written as a sum usually reflects the fact that it is invariant under the action of a group symmetry, such as translational invariance. Such symmetries can be discrete or continuous; they materialize in the correlation functions for the random variables (discussed below). Thus a symmetry in the Hamiltonian becomes a symmetry of the correlation function (and vice versa).

This symmetry has a critically important interpretation in probability theory: it implies that the Gibbs measure has the Markov property; that is, it is independent of the random variables in a certain way, or, equivalently, the measure is identical on the equivalence classes of the symmetry. This leads to the widespread appearance of the partition function in problems with the Markov property, such as Hopfield networks.

As a measure

The value of the expression

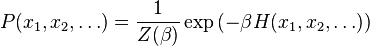

can be interpreted as a likelihood that a specific configuration of values  occurs in the system. Thus, given a specific configuration

occurs in the system. Thus, given a specific configuration  ,

,

is the probability of the configuration  occurring in the system, which is now properly normalized so that

occurring in the system, which is now properly normalized so that  , and such that the sum over all configurations totals to one. As such, the partition function can be understood to provide a measure (a probability measure) on the probability space; formally, it is called the Gibbs measure. It generalizes the narrower concepts of the grand canonical ensemble and canonical ensemble in statistical mechanics.

, and such that the sum over all configurations totals to one. As such, the partition function can be understood to provide a measure (a probability measure) on the probability space; formally, it is called the Gibbs measure. It generalizes the narrower concepts of the grand canonical ensemble and canonical ensemble in statistical mechanics.

There exists at least one configuration  for which the probability is maximized; this configuration is conventionally called the ground state. If the configuration is unique, the ground state is said to be non-degenerate, and the system is said to be ergodic; otherwise the ground state is degenerate. The ground state may or may not commute with the generators of the symmetry; if commutes, it is said to be an invariant measure. When it does not commute, the symmetry is said to be spontaneously broken.

for which the probability is maximized; this configuration is conventionally called the ground state. If the configuration is unique, the ground state is said to be non-degenerate, and the system is said to be ergodic; otherwise the ground state is degenerate. The ground state may or may not commute with the generators of the symmetry; if commutes, it is said to be an invariant measure. When it does not commute, the symmetry is said to be spontaneously broken.

Conditions under which a ground state exists and is unique are given by the Karush–Kuhn–Tucker conditions; these conditions are commonly used to justify the use of the Gibbs measure in maximum-entropy problems.

Normalization

The values taken by  depend on the mathematical space over which the random field varies. Thus, real-valued random fields take values on a simplex: this is the geometrical way of saying that the sum of probabilities must total to one. For quantum mechanics, the random variables range over complex projective space (or complex-valued projective Hilbert space), where the random variables are interpreted as probability amplitudes. The emphasis here is on the word projective, as the amplitudes are still normalized to one. The normalization for the potential function is the Jacobian for the appropriate mathematical space: it is 1 for ordinary probabilities, and i for Hilbert space; thus, in quantum field theory, one sees

depend on the mathematical space over which the random field varies. Thus, real-valued random fields take values on a simplex: this is the geometrical way of saying that the sum of probabilities must total to one. For quantum mechanics, the random variables range over complex projective space (or complex-valued projective Hilbert space), where the random variables are interpreted as probability amplitudes. The emphasis here is on the word projective, as the amplitudes are still normalized to one. The normalization for the potential function is the Jacobian for the appropriate mathematical space: it is 1 for ordinary probabilities, and i for Hilbert space; thus, in quantum field theory, one sees  in the exponential, rather than

in the exponential, rather than  . The partition function is very heavily exploited in the path integral formulation of quantum field theory, to great effect. The theory there is very nearly identical to that presented here, aside from this difference, and the fact that it is usually formulated on four-dimensional space-time, rather than in a general way.

. The partition function is very heavily exploited in the path integral formulation of quantum field theory, to great effect. The theory there is very nearly identical to that presented here, aside from this difference, and the fact that it is usually formulated on four-dimensional space-time, rather than in a general way.

Expectation values

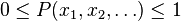

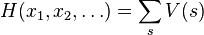

The partition function is commonly used as a generating function for expectation values of various functions of the random variables. So, for example, taking  as an adjustable parameter, then the derivative of

as an adjustable parameter, then the derivative of  with respect to

with respect to

gives the average (expectation value) of H. In physics, this would be called the average energy of the system.

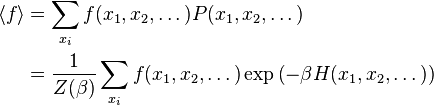

Given the definition of the probability measure above, the expectation value of any function f of the random variables X may now be written as expected: so, for discrete-valued X, one writes

The above notation is strictly correct for a finite number of discrete random variables, but should be seen to be somewhat 'informal' for continuous variables; properly, the summations above should be replaced with the notations of the underlying sigma algebra used to define a probability space. That said, the identities continue to hold, when properly formulated on a measure space.

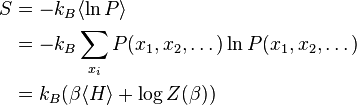

Thus, for example, the entropy is given by

The Gibbs measure is the unique statistical distribution that maximizes the entropy for a fixed expectation value of the energy; this underlies its use in maximum entropy methods.

Information geometry

The points  can be understood to form a space, and specifically, a manifold. Thus, it is reasonable to ask about the structure of this manifold; this is the task of information geometry.

can be understood to form a space, and specifically, a manifold. Thus, it is reasonable to ask about the structure of this manifold; this is the task of information geometry.

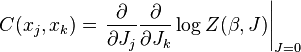

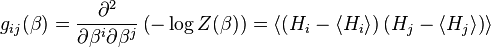

Multiple derivatives with regard to the Lagrange multipliers gives rise to a positive semi-definite covariance matrix

This matrix is positive semi-definite, and may be interpreted as a metric tensor, specifically, a Riemannian metric. Equipping the space of lagrange multipliers with a metric in this way turns it into a Riemannian manifold.[1] The study of such manifolds is referred to as information geometry; the metric above is the Fisher information metric. Here,  serves as a coordinate on the manifold. It is interesting to compare the above definition to the simpler Fisher information, from which it is inspired.

serves as a coordinate on the manifold. It is interesting to compare the above definition to the simpler Fisher information, from which it is inspired.

That the above defines the Fisher information metric can be readily seen by explicitly substituting for the expectation value:

where we've written  for

for  and the summation is understood to be over all values of all random variables

and the summation is understood to be over all values of all random variables  . For continuous-valued random variables, the summations are replaced by integrals, of course.

. For continuous-valued random variables, the summations are replaced by integrals, of course.

Curiously, the Fisher information metric can also be understood as the flat-space Euclidean metric, after appropriate change of variables, as described in the main article on it. When the  are complex-valued, the resulting metric is the Fubini–Study metric. When written in terms of mixed states, instead of pure states, it is known as the Bures metric.

are complex-valued, the resulting metric is the Fubini–Study metric. When written in terms of mixed states, instead of pure states, it is known as the Bures metric.

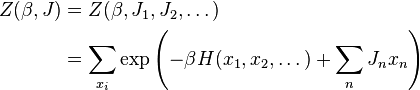

Correlation functions

By introducing artificial auxiliary functions  into the partition function, it can then be used to obtain the expectation value of the random variables. Thus, for example, by writing

into the partition function, it can then be used to obtain the expectation value of the random variables. Thus, for example, by writing

one then has

as the expectation value of  . In the path integral formulation of quantum field theory, these auxiliary functions are commonly referred to as source fields.

. In the path integral formulation of quantum field theory, these auxiliary functions are commonly referred to as source fields.

Multiple differentiations lead to the connected correlation functions of the random variables. Thus the correlation function  between variables

between variables  and

and  is given by:

is given by:

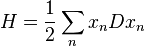

For the case where H can be written as a quadratic form involving a differential operator, that is, as

then the correlation function  can be understood to be the Green's function for the differential operator (and generally giving rise to Fredholm theory). In the quantum field theory setting, such functions are referred to as propagators; higher order correlators are called n-point functions; working with them defines the effective action of a theory.

can be understood to be the Green's function for the differential operator (and generally giving rise to Fredholm theory). In the quantum field theory setting, such functions are referred to as propagators; higher order correlators are called n-point functions; working with them defines the effective action of a theory.

General properties

Partition functions are used to discuss critical scaling, universality and are subject to the renormalization group.

See also

References

- ↑ Gavin E. Crooks, "Measuring thermodynamic length" (2007), ArXiv 0706.0559

![Z = \int \mathcal{D} \phi \exp \left(- \beta H[\phi] \right)](../I/m/a754ce2156da0ed081f4e1efaea74091.png)

![Z(\beta) = \mbox{tr}\left[\,\exp \left(-\sum_k\beta_k H_k\right)\right]](../I/m/b4d7f7fad3b3afd5803173464618091e.png)

![\frac{\partial}{\partial \beta_k} \left(- \log Z \right) = \langle H_k\rangle = \mathrm{E}\left[H_k\right]](../I/m/f80aed7b9f44b9144f842b538f9081e3.png)

![\bold{E}[H] = \langle H \rangle = -\frac {\partial \log(Z(\beta))} {\partial \beta}](../I/m/fa11d5b9c468396b50734d7980224233.png)

![\bold{E}[x_k] = \langle x_k \rangle = \left.

\frac{\partial}{\partial J_k}

\log Z(\beta,J)\right|_{J=0}](../I/m/6901329023a9b52d744390748c6053d4.png)