Parischnogaster jacobsoni

| Parischnogaster jacobsoni | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

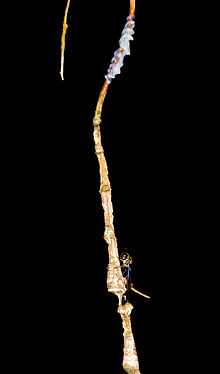

| A colony of Parischnogaster jacobsoni | |

| Conservation status | |

| Not evaluated (IUCN 3.1) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Vespidae |

| Genus: | Parischnogaster |

| Species: | P. jacobsoni |

| Binomial name | |

| Parischnogaster jacobsoni (Robert du Buysson, 1913) | |

Parischnogaster jacobsoni is a species of social wasp within Parischnogaster, the largest and least known genus of Stenogastrinae. It is distinguished mainly by its tendency to construct ant guards on its nests.[1] Natural selection has led this wasp to have a thick substance emitted from its abdominal glands that allows it to protect its nest from invasions. Parischnogaster as a genus has been relatively unstudied; P. jacobsoni is one of the few investigated species because it has sufficient durability to live near human populations and it has demonstrated unusual resilience to pollution. While P. jacobsoni is a more complex organism than other wasps in Parischnogaster, the genus overall is relatively primitive with respect to social wasps as a whole.[2]

Taxonomy and phylogeny

The French entomologist Robert du Buysson described Parischnogaster jacobsoni in 1913. The species has no common name. Most common in Malaysia, stenogastrine wasps like P. jacobsoni wasps are generally found in South-East Asian rainforests.[1] P. jacobsoni falls within the genus Parischnogaster, which is one subset of the hover wasps, or Stenogastrinae. Its relatively primitive traits are key to describing the evolution of social behavior in wasps.[3]

Description and identification

P. jacobsoni, like all Parischnogaster wasps, has a wide, short head, though the width of its head is smaller than other Parischnogaster wasps. The larvae also present with much smaller salivary glands than larvae belonging to Polistes and Vespula species, indicating that trophallaxis does not occur with P. jacobsoni wasp offspring.[4] Parischnogaster females present with shiny black or dark brown coloration, whereas males have gastral terga striped with white to mark them out during aerial patrols.[2] Males of the species can be identified as distinct from P. nigricans serrei, their closest cousin, because of a knife-like spine in the center of the clypeus.[5]

The nests of P. jacobsoni generally reach their maximum size at 48 cells, and can house up to 6 females and 6 males, as well as a total of 33 larvae in a brood.[6] P. jacobsoni wasps always use plant matter to construct their nests. They are composed of one or two linear rows anchored on a slim support or scattered across a flat surface. According to the theory that conserving material by utilizing wall-sharing cells and constructing structures to protect the nest are evidence of evolved wasp characters, P. jacobsoni constructs nests that are perhaps the most primitive of all wasp nests. It has almost no wall-sharing whatsoever, with cells scattered across the underside of a leaf.[2] The nest, similar to that of P. nigricans serrei, differs particularly because the alveolar walls are adjoined to the neighboring cells and because pupal cells, instead of being sealed, are simply narrowed.[5]

Habitat

Like all Parischnogaster wasps, P. jacobsoni builds nests rather than living in open habitats.[2] However, P. jacobsoni generally has been found to build nests mostly in open spaces and even on or near man-made structures.[5] The species is scattered throughout Southeast Asian rainforests and is most commonly found in Malaysia.[3] Like all Stenogastrinae, wasps of P. jacobsoni prefer to nest in very humid environments in the rainforest, near streams or waterfalls, or on the surfaces of caves. They also can live near human settlements, which may explain, at least in part, why this species of Parischnogaster is one of relatively few that has been discovered.[6]

Colony cycle

The foundation of each nest is generally by a single female founder haplometrotically. It is possible, rarely, for two females to cohabit a colony at its founding, but this scenario does not represent the norm. There are a limited number of females per colony, suggesting that the females tend to abandon the colony once they achieve a certain level of ovarian development. Nevertheless, because satisfactory sites for nidification are rare, there is a large number of females without colonies that are looking for a good region on which to found a nest, or a nest that they could strategically usurp. As a result, the rare cases where there are two females at foundation are more likely to be a form of usurpation rather than cooperation.[5] Researchers have yet to perform long-term studies on P. jacobsoni; like most hover wasps, P. jacobsoni has not undergone long-term observation so there is only limited information on their colony cycles. Similar Parischnogaster species, however, demonstrate a five stage colony cycle, with a pre-emergence period divided into foundation and initial nest segments, and a post-emergence period divided into young colony, middle-age colony and mature colony segments.[6]

Behavior

Dominance hierarchy

The behavior of female P. jacobsoni include various interactions with other wasps including begging, dominance hierarchies, pursuit, avoidance, and aggression. As a result, the behavior of the wasp is to a large extent social.[5] Dominant individuals in P. jacobsoni nests, for example, will cow subordinate wasps into submission as they crawl through their nests. Subordinates, in turn, attempt to avoid the dominant; however, when avoidance is impossible, they halt completely, turn their head to the side and, after being inspected by the antennae of the dominant individual (often considered to be a form of solicitation), emit fluid that the dominant often sucks up.[7] Subordinate wasps often will flee interactions with the dominant wasp. Potential egg laying (PEL) females are less likely than other females to leave the nest and are also more dominant. Otherwise, they behave similarly to other females. Dominance in females is usually correlated with the size of their ovaries. Interactions between nestmates are relatively rare when compared to other wasp species; as a result, only the first ranks of dominance hierarchies are actually established and the females with low ovarian development do not participate in dominance at all.[5]

Division of labor

Relative to the other species of Parischnogaster, P. jacobsoni seems to demonstrate a higher relative level of complexity because it has relatively larger colonies, defined social hierarchies, and labor division schemes. In all Stenogastrinae wasps, division of labor is determined by dominance hierarchies based on some defining physical characteristic of the wasps in question. Particularly for the P. jacobsoni wasp, the reproductive capacity of the females in a colony determines the structured division of labor observed in their nests.[5] The alpha female with the largest ovaries will remain in the nest for most of her day, limiting herself to patrolling the nest and asserting her dominance over the other wasps or resting. The females with very low levels of ovarian development will generally avoid the nest altogether.[6] Rarely, this division of labor is reversed and females with developed ovaries are subordinate to those with less reproductive potential. This type of system occurs when old alpha females are ousted by younger ones. In addition, after the emergence of the first daughter, the original foundress may become a primary forager for the colony.[5]

Reproductive suppression

Domination acts by alpha females are often directed toward wasps with nearly as developed ovaries. Those females in turn act dominantly over other females in the colony, other than the alpha female. The females with poorly developed ovaries, on the other hand, almost never act in a dominant way. Undeveloped ovaries of those least dominant females appear white and thread-like with no sign of egg reabsorption, demonstrating the young age of a female wasp. Dominant females’ acts of aggression can likely inhibit ovarian development for other females, which would explain why alpha females center their dominance interactions on females with the second most developed ovaries, so that those second most developed females cannot establish themselves enough to usurp the alpha wasp's position. This process of ovarian development suppression is common to other species of the family Vespidae.[5]

Communication

Adult recognition

P. jacobsoni wasps have a sophisticated system of nestmate recognition that has high fidelity. They attack conspecific strangers and allow nestmates to pass. In an experiment using corpses of nestmates and other conspecific wasps, the nestmate recognition system held, suggesting that the recognition system is a passive component of the wasp. P. jacobsoni is capable of recognizing immature broods as well, killing/eliminating the eggs and younger larvae of alien wasps selectively.[8]

Nest and brood recognition

P. jacobsoni females are able to recognize and reject conspecific females of foreign colonies; however, they will accept alien nests located in the same place as their own was. The exact location of the new nest in the position of the true nest might be a deceiving factor, but they still seem able to recognize a different brood within the nest, evidenced by higher activity of behavior in experimentally switched nests versus control nests. Nevertheless, P. jacobsoni will potentially completely accept an alien nest and an unrelated immature brood (the likelihood of this increases with the relative immaturity of the brood). This adoption of an unrelated brood may stem from a heavier investment in offspring of Stenogastrinae wasps versus other social wasps. Polistines, for example, completely destroy immature broods of alien wasps. Stenogastrinae wasps, on the other hand invest heavily with the deposition and provision of an abdominal substance, an allocation that is greater than the simple food and liquid allocation of other wasp species. As such, there is a greater investment in larval rearing for the Stenogastrinae wasp versus other wasp species. It is also possible that the female keeps the unrelated brood long enough for her to need to lay her own eggs, at which point she will eat the brood to give her an energetic boost for establishing her own brood.[3]

Abdominal secretion

The Dufour's gland of wasps in P. jacobsoni is relatively enlarged when compared to other social wasps and secretes a substance similar to the abdominal substance secreted by those wasps. However, in addition to its conserved uses, the abdominal substance from the Dufour’s gland can be used in a different context as an ant guard.[9] In addition to its role in nest protection, the substance secreted via the Dufour’s gland is vital to brood rearing as well as oviposition and self-grooming.[5] P. jacobsoni also produces richer secretions from its Dufour’s gland than various species that do not produce ant guards including L. flavolineata and P. mellyi. The contents of that gland, then, may have been naturally selected for their efficiency in defense and protection of the nest, via differential success of substances that do and do not produce ant guards.[2] The ability of Parischnogaster species to excrete a white, gelatinous substance that they use for various functions distinguishes them from other wasp species.[9]

Reproduction and child-rearing

P. jacobsoni wasps reproduce via oviposition. Egg laying is divided into three stages. First, the female produces a substance from the Dufour’s gland and collects a patch of it in her mouth. Then, after stretching the gaster, the wasp brings it back toward her mouth and collects the eggs as they emerge, adhering them to the original secretion. The egg is then affixed to the nest cell via another patch of secretion. Finally, another deposition of the abdominal secretion is placed on the original secretion on the concave surface of the egg.[10] The various functions of the abdominal substance in child-rearing include serving as the substratum to protect young larva, as a dish for larval food, and as a place to store reserves of liquid food. It is not, however, used as a larval food itself. Instead it is used to protect sugary and protein heavy foods collected from the environment by adults.[9]

The secretion expelled onto the eggs as well as the secretion used as an ant guard contain similar rations of the same hydrocarbons. The egg secretion is a mixture of the Dufour's gland secretion and nectar consisting of fructose and water, using palmitic acid salt as an emulsifying agent.[9]

Self-grooming

Self-grooming among P. jacobsoni wasps is similar to the use of Dufour’s gland secretion to establish the ant guard for the nest because the fundamental movements that the wasp uses are the same for both behaviors. The key difference lies in the fact that during self-grooming, the secretion is spread all over the wasp's body, while when establishing the ant guard, it is not. This process of rubbing the secretion all over the wasp's own body is known to confer a certain level of protection from pathogens because it constitutes a physical barrier that prevents dust and small particles from entering the wasp. The conservation in behavior is reflected in a conservation of chemicals; the cuticular hydrocarbons are similar in composition to the chemicals in the Dufour’s gland.[7]

Daily activity

The species P. jacobsoni is most likely to be present on its nest during dawn and dusk while it is most likely to be absent from its nest during midday.[7] For the foundresses in particular, each day their distribution of behavior is codified by time. Major periods of activity occur in the morning (specifically for nest building) and the evening (for ant guard construction).[5]

When adult P. jacobsoni wasps rest, they tend to rest in specific patterns on the nest with respect to the locations of the young brood. When they go to meet returning P. jacobsoni foragers, they will attempt to snag the lumps of food carried by the foragers. They will begin to chew the food, using their heads to leverage against the forager’s head. Unlike with food requests, fluid requests involve more solicitation, as the beggar will tap its partner slowly and lightly with its antennae until the forager emits fluid that will be sucked up by the beggar.[7]

Strategic nest position

P. jacobsoni builds nests in isolation. The nests are usually long and consist of several cells that are attached to a thread-like substrata and protected using ant-guards.[3] What these nests lack in structural rigor they make up in camouflage; they are generally nearly invisible among their surroundings. Some wasps of this species, for example, implant cells on the bottoms of leaves.[2] Another significant benefit of building nests on the underside of leaves is that they are sheltered from the rain.[9] Furthermore, while P. jacobsoni does not generally nest in clusters, associative foundations are occasionally found where a high density of wasps protects against various terrestrial predators.[6]

Nest defense

Against small intruders

The main physical defense to the nest is the ant guard. Wasps that build their nests on the underside of leaves will add an ant guard to the stem to prevent ants from attacking the nest.[2] Ant guard construction is a behavior peculiar to P. jacobsoni among its genus, although it does occur in some wasps in the genera Eustenogaster and Liostenogaster via a radically different behavioral mechanism.[7] In P. jacobsoni, the ant guard construction is simply a smear of secretion from the Dufour’s gland on the nest that forms a sticky obstacle to ants attempting to invade the cells; this prevent ants from attacking, which differs from other social wasps that actually construct physical impediments to ants.[2][9] The ant guard is always added to protect the nest, however, and immediately following the building of the first cell, the ant guard is laid down by the wasp.[5]

The wasp will defend the nest from conspecific intruders as well.[5] When defending the nest from other flying objects, as soon as some flying movement is detected, the resident wasps begin to follow the object. If the object is small enough to be a conspecific wasp intruder, resident females will begin to buzz their wings and batter it in midair.[7]

Against large intruders

P. jacobsoni wasps tend to be resistant to pollution, including areas heavily populated by humans. As a result, they are more prone to disturbance by humans than other Parischnogaster species.[2] In fact, the wasp generally flees when the nest is disturbed; rather than attacking disturbances larger than a conspecific wasp or an ant, it will drop away from it passively. As a result, size is key to differentiation of the disturbances that it will attack or avoid. This tactic also may confuse a predator, masking the location of the nest and defending it against the predator.[11]

Sting and venom

While the wasp has both the ability to sting and a functional venom apparatus, rarely does it demonstrate aggression against predators. With respect to humans, the sting is far less painful than those of other social wasps. Nevertheless, the proteins in the venom of Stenogastrinae remain unstudied and so its exact properties are unknown.[11]

Venom composition

The volatile compound in venom sacs of P. jacobsoni wasps consists of a mixture of chains of alkanes and alkenes ranging from eleven to seventeen carbons in length. The venom sacs of P. jacobsoni hold relatively little venom, on average around 1500 ng; however, that value varies greatly from wasp to wasp. For P. jacobsoni, the venom is characterized by the major compound tridecane and by the presence of large amounts of undecane and pentadecane. There are also some spiroacetals that are not found in other Parischnogaster wasps that are found in P. jacobsoni venom. Some studies have shown that dead wasps treated with some spiroacetal compounds including those found in P. jacobsoni were less attacked by conspecifics than untreated ones. The spiroacetals also played a role in repelling or attracting wasps, depending on the concentration.[11]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Turillazzi, Stefano. "The Hover Wasps." The Biology of Hover Wasps. Dordrecht: Springer, 2012. 1–25. Springer Link. Web. 13 Oct. 2014. <http://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-3-642-32680-6_1.pdf>.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 Turillazzi, Stefano. "The Nest of Hover Wasps." The Biology of Hover Wasps. Dordrecht: Springer, 2012. 149–231. Springer Link. Web. 13 Oct. 2014. <http://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-3-642-32680-6_6.pdf>.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Cervo, R., Francesca R. Dani, and Stefano Turillazzi. "Nestmate Recognition in Three Species of Stenogastrine Wasps (Hymenoptera, Vespidae)." Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 39.5 (1996): 311–16. Springer. Web. 13 Oct. 2014. <http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs002650050294#page-1>.

- ↑ Turillazzi, Stefano. "Morphology and Anatomy." The Biology of Hover Wasps. Dordrecht: Springer, 2012. 27–60. Springer Link. Web. 13 Oct. 2014. <http://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-3-642-32680-6_2.pdf>.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 5.9 5.10 5.11 5.12 Turillazzi, Stefano. "Social Biology of Parischnogaster Jacobsoni (Du Buysson) (Hymenoptera Stenogastrinae)." Insectes Sociaux 35.2 (1988): 133–43. Springer Link. 17 Oct. 1988. Web. 17 Oct. 2014. <http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2FBF02223927>.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Turillazzi, Stefano. "Colonial Dynamics." The Biology of Hover Wasps. Dordrecht: Springer, 2012. 89–127. Springer Link. Web. 13 Oct. 2014. <http://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-3-642-32680-6_4.pdf>.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Turillazzi, Stefano. "Behaviour." The Biology of Hover Wasps. Dordrecht: Springer, 2012. 61–87. Springer Link. Web. 13 Oct. 2014. <http://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-3-642-32680-6_3.pdf>.

- ↑ Turillazzi, Stefano. "Social Communication in Hover Wasps." The Biology of Hover Wasps. Dordrecht: Springer, 2012. 129–148. Springer Link. Web. 13 Oct. 2014. <http://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-3-642-32680-6_5.pdf>.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Keegans, Sarah J., E. David Morgan, Stefano Turillazzi, Brian D. Jackson, and Johan Billen. "The Dufour Gland and the Secretion Placed on Eggs of Two Species of Social Wasps,Liostenogaster Flavolineata and Parischnogaster Jacobsoni (Vespidae: Stenogastrinae)." Journal of Chemical Ecology 19.2 (1993): 279–90. Springer Link. Web. 12 Oct. 2014. <http://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2FBF00993695.pdf>.

- ↑ Turillazzi, Stefano. "Egg Deposition in the Genus Parischnogaster (Hymenoptera: Stenogastrinae)." Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 58.4 (1985): 749–52. JSTOR. Web. 14 Oct. 2014. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdfplus/25084724.pdf>.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Dani, Francesco R., E. D. Morgan, Graeme R. Jones, Stefano Turillazzi, Rita Cervo, and Wittko Francke. "Species-Specific Volatile Substances in the Venom Sac of Hover Wasps." Journal of Chemical Ecology 24.6 (1998): 1091–104. Springer Link. Web. 15 Oct. 2014. <http://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1023%2FA%3A1022358604352.pdf>.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Parischnogaster jacobsoni. |