Paraguayan War

| Paraguayan War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Allies

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ca. 300,000 soldiers and civilians |

71,000 Brazilian imperial soldiers 20,000 Argentine soldiers 3,200 Uruguayan soldiers Total: +100,000 soldiers and civilians | ||||||

| ||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Paraguay |

|

| Paraguay portal |

The Paraguayan War (Spanish: Guerra del Paraguay; Portuguese: Guerra do Paraguai), also known as the War of the Triple Alliance (Spanish: Guerra de la Triple Alianza; Portuguese: Guerra da Tríplice Aliança), and in Paraguay as the "Great War" (Spanish: Guerra Grande, Guarani: Ñorairõ Guazú),[1][2] was an international military conflict in South America fought from 1864 to 1870 between Paraguay and the Triple Alliance of Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay. It caused approximately 400,000 deaths, one of the highest ratios of fatalities to combatants of any war in South America in modern history. It particularly devastated Paraguay, which suffered catastrophic losses in population--almost 70% of its adult male population died--and was forced to cede territory to Argentina and Brazil.

There are several theories regarding the origins of the war. The traditional view emphasizes the aggressive policy of Paraguayan president Francisco Solano López to gain control in the Platine basin. See also Fortress of Humaitá. Conversely, popular belief in Paraguay, and Argentine revisionism since the 1960s, blames the influence of the British Empire (though the academic consensus shows little evidence for this theory).[3] The war has also been attributed to the after-effects of colonialism in South America; the struggle for physical power among neighboring nations over the strategic Río de la Plata region; Brazilian and Argentine meddling in internal Uruguayan politics; Solano López's efforts to help allies in Uruguay (previously defeated by Brazilians), as well as his presumed expansionist ambitions.[4] Paraguay had recurring boundary disputes and tariff issues with Argentina and Brazil for many years; its aid to allies in Uruguay in the period before the war worsened its relations with those countries.

The war began in late 1864 with combat operations between Brazil and Paraguay. Argentina and Uruguay entered in 1865, and it became the "War of the Triple Alliance."

The outcome of the war was the utter defeat of Paraguay. After it lost in conventional warfare, Paraguay conducted a drawn-out guerrilla-style resistance, a disaster that resulted in the destruction of the Paraguayan military and much of the civilian population. The guerrilla war lasted until López was killed by Brazilian forces on 1 March 1870. Estimates of total Paraguayan losses range from 300,000 to 1,200,000. It took decades for Paraguay to recover from the chaos and demographic imbalance.

In Brazil the war helped bring about the end of slavery, moved the military into a key role in the public sphere and caused a ruinous increase of public debt, which took a decade to pay off, seriously reducing the country's growth. It has been argued the war played a key role in the consolidation of Argentina as a nation-state.[5] That country became South America's wealthiest nation, and one of the wealthiest in the world, by the early 20th century.[6] It was the last time that Brazil and Argentina took such an interventionist role in Uruguay's internal politics.[7]

Background

Paraguay

Paraguay under José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia (1813–1840) and Carlos Antonio López (1841–1862) developed quite differently from other South American nations. These two leaders encouraged self-sufficient economic development, imposing a high level of isolation from neighboring countries.[8]

The regime of the López family was characterized by pervasive and rigid centralism in production and distribution. There was no distinction between the public and the private sphere, and the López family ruled the country as it would a large estate.[9]

The government exerted control on all exports. The export of yerba mate and valuable wood products maintained the balance of trade between Paraguay and the outside world.[10] The Paraguayan government was extremely protectionist, never accepted loans from abroad and levied high tariffs against imported foreign products. This protectionism made the society self-sufficient, and it also avoided the debt suffered by Argentina and Brazil. Francisco Solano López, the son of Carlos Antonio López, replaced his father as the President-Dictator in 1862, and he generally continued the political policies of his father.

Militarily, Solano López modernized and expanded industry and the Paraguayan Army.[11] The government hired more than 200 foreign technicians, who installed telegraph lines and railroads to aid the expanding steel, textile, paper and ink, naval construction, weapons and gunpowder industries. The Ybycuí foundry, completed in 1850, manufactured cannons, mortars and bullets of all calibers. River warships were built in the shipyards of Asunción. Fortifications were built, especially along the Apa River and in Gran Chaco.[12]:22

After the Cruzada Libertadora started by Venancio Flores in Uruguay, López sent a demand on 6 Sept. 1863 to the Argentine government asking for an explanation.[12]:24 Though mandatory military service was already in effect in Paraguay, in Feb. 1864 an additional 64,000 men were drafted into the army.[12]:24 On 12 Nov. The Brazilian Minister in Asuncion received a letter stating Paraguay was severing diplomatic relations, and the Paraná River and Paraguay River were closed to Brazilian shipping.[12]:24

Brazil

Since Brazil and Argentina had become independent, their struggle for hegemony in the Río de la Plata profoundly marked the diplomatic and political relations among the countries of the region.[13]

Brazil, under the rule of the Portuguese, was the first country to recognize the independence of Paraguay, in 1811. While Argentina was ruled by Juan Manuel Rosas (1829–1852), a common enemy of both Brazil and Paraguay, Brazil contributed to the improvement of the fortifications and development of the Paraguayan army, sending officials and technical help to Asunción. As no roads linked the province of Mato Grosso to Rio de Janeiro, Brazilian ships needed to travel through Paraguayan territory, going up the Río Paraguay to arrive at Cuiabá. Many times, however, Brazil had difficulty obtaining permission from the government in Asunción to sail those waterways.

Brazil carried out three political and military interventions in Uruguay: in 1851, against Manuel Oribe to fight Argentine influence in the country; in 1855, at the request of the Uruguayan government and Venancio Flores, leader of the Colorados, who were traditionally supported by the Brazilian empire; and in 1864, against Atanasio Aguirre. This last intervention would light the fuse for the Paraguayan War.

Uruguay

On 19 April 1863 former Colorado President of Uruguay Venancio Flores returned his refuge in Argentina, at the head of army in the Cruzada Libertadora, intending to depose the Blanco President of Uruguay, Bernardo Berro.[12]:24

In April 1864 Brazil sent a diplomatic mission to Uruguay, led by José Antônio Saraiva, to demand payment for damages caused to gaucho farmers in border conflicts with Uruguayan farmers. Uruguayan President Atanasio Aguirre, of the National Party (Blanco Party), refused the Brazilian demands.

Solano López offered himself as mediator, but was turned down by Brazil. Diplomatically, Solano López was allied with Uruguay's ruling party. After the Colorado Party in Uruguay became allied with Brazil and Argentina.,[14] López thought the balance of power was threatened by Brazil's involvement in Uruguay's internal politics and struggle for leadership. López broke diplomatic relations with Brazil in August 1864 and declared that the occupation of Uruguay by Brazilian troops would be an attack on the equilibrium of the Río de la Plata region.

On October 12 1864 Brazilian troops under the command of Gen. João Propício Mena Barreto invaded Uruguay.[12]:24 The followers of Colorado party leader Venancio Flores, who had the support of Argentina, united with the Brazilian troops and deposed Aguirre.[15] On 28 Jan. 1865 Flores signed a formal alliance with Brazil against Paraguay.[12]:30

Argentina

When war first broke out between Paraguay and Brazil, Argentina stayed neutral. Solano López doubted Argentina's neutrality, because it gave Brazilian ships permission to navigate in the Argentine rivers of the Plate region--the same rights it gave to Paraguay, which shared the river. When Lopez asked to move his troops through Argentine territory, to fight in Uruguay against Brazil, Argentina rejected the request. Paraguay sent its forces into the Corrientes Province of Argentina on 13 April 1865, declaring war on Argentina, after which Argentina declared war on Paraguay on 9 May.[12]:30-31 The Treaty of the Triple Alliance was signed on 1 May 1865.[12]:31

Britain

Some historians (of the 1960s and 1970s) claimed the Paraguayan War was caused by the pseudo-colonial influence of the British,[16][17] who needed a new source of cotton during the United States Civil War (as the blockaded southern states had been their main cotton supplier).[18] But other historians dispute this claim of British influence, saying there is no documentary evidence for it.[19][3] They note that, although the British economy and commercial interests benefited from the war, the UK government opposed it from the start. It believed that war damaged international commerce, and disapproved of the secret clauses in the Treaty of the Triple Alliance. Britain already was increasing imports of Egyptian cotton and did not need Paraguayan products.[20] Sir Edward Thornton, the British Minister to the Argentine Republic, personally supported the Triple Alliance; he was present at the signing of a treaty of alliance between Brazil and Argentina on 18 June 1864 in Puntas del Rosario. Journalist Jose Antonio Saraiva later declared this to be the real start of the alliance, suggesting that the British interest catalyzed the other two nations to mobilize against Paraguay.[20][21] William Doria (the UK Chargé d'Affairs for Paraguay who briefly acted for Thornton) joined French and Italian diplomats in condemning Argentina's President Bartolomé Mitre's involvement in Uruguay. But when Thornton returned to the job in December 1863, he threw his full backing behind Mitre.[20]

Course of the war

War is declared

When the Uruguayan Blancos were attacked by Brazil, they asked for help from Paraguay. On 12 November 1864 the Paraguayan ship Tacuarí captured the Brazilian ship Marquês de Olinda, which had sailed up the Río Paraguay to the province of Mato Grosso.[22] On 13 December Paraguay declared war on Brazil. Three months later, on 18 March 1865, Paraguay declared war on Argentina. By then the Uruguayan War was over, with Venancio Flores ruling and Uruguay now aligned with Brazil and Argentina.

According to some historians, Paraguay began the war with over 60,000 well-trained men--38,000 of whom were currently under arms--400 cannons, a naval squadron of 23 steamboats (vapores) and five river-navigating ships (among them the Tacuarí gunboat).[23] However, recent studies suggest many problems. Although the Paraguayan army had between 70,000 and 100,000 men at the beginning of the conflict, they were badly equipped. Most infantry armaments consisted of inaccurate smooth-bore muskets and carbines, slow to reload and short-ranged. The artillery was similarly poor. Military officers had no training or experience, and there was no command system, as all decisions were made by López. Food, ammunition and armaments were scarce, with logistics and hospital care deficient or nonexistent.[24]

At the beginning of the war the military forces of Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay were far smaller than Paraguay's. Argentina had approximately 8,500 regular troops and a naval squadron of four vapores and one goleta. Uruguay entered the war with fewer than 2,000 men and no navy. Many of Brazil's 16,000 troops were located in its southern garrisons.[25] The Brazilian advantage, though, was in its navy, comprising 42 ships with 239 cannons and about 4,000 well-trained crew. A great part of the squadron had already met in the Rio de la Plata basin, where it had acted under the Marquis of Tamandaré in the intervention against Aguirre.

Brazil, however, was unprepared to fight a war. Its army was disorganized. The troops it used in Uruguay were mostly armed contingents of gauchos and National Guard. While some Brazilian accounts of the war described their infantry as volunteers (Voluntários da Pátria), other Argentinian revisionist and Paraguayan accounts disparaged the Brazilian infantry as mainly recruited from slaves and the landless (largely black) underclass, promised free land for enlisting.[26] The cavalry was formed from the National Guard of Rio Grande do Sul. (Ultimately, a total of about 146,000 Brazilians fought from 1864 to 1870, consisting of 10,025 army soldiers stationed in Uruguayan territory in 1864, 2,047 that were in the province of Mato Grosso, 55,985 Fatherland Volunteers, 60,009 National Guards, 8,570 ex-slaves who had been freed to be sent to war, and 9,177 navy personnel. Another 18,000 National Guard troops stayed behind to defend Brazilian territory.[27])

On 1 May 1865 Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay signed the secret Treaty of the Triple Alliance in Buenos Aires. They named Bartolomé Mitre, president of Argentina, as supreme commander of the allied forces.[28]

Paraguayan offensive

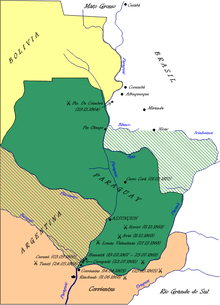

Paraguay took the initiative during the first phase of the war, invading Mato Grosso in the north on 14 December 1864,[12]:25 Rio Grande do Sul in the south in early 1865 and the Argentine province of Corrientes.

Two separate Paraguayan forces invaded Mato Grosso simultaneously. An expedition of 3,248 troops, commanded by Col. Vicente Barrios, was transported by a naval squadron under the command of Capitan de Fragata Pedro Ignacio Meza, up the Río Paraguay to the town of Concepcion.[12]:25 They attacked the Nova Coimbra fort on 27 Dec.[12]:26 The Brazilian garrison of 154 men resisted for three days, under the command of Lt. Col. Hermenegildo de Albuquerque Porto Carrero (later Baron of Fort Coimbra). When their munitions were exhausted, the defenders abandoned the fort and withdrew up the river towards Corumbá on board the gunship Anhambaí.[12]:26 After occupying the fort, the Paraguayans advanced north, taking the cities of Albuquerque, Tage and Corumbá in January 1865.[12]:26 López then sent a detachment to attack the military frontier post of Dourados. This detachment, led by Maj. Martín Urbieta, encountered tough resistance on 29 December 1864 from Lt. Antonio João Ribeiro and his 16 men, who were all eventually killed. The Paraguayans continued to Nioaque and Miranda, defeating the troops of Col. José Dias da Silva. Coxim was taken in April 1865. The second Paraguayan column, formed from some of the 4,650 men led by Col. Francisco Isidoro Resquín at Concepcion, penetrated into Mato Grosso with 1500 troops.[12]:26

Despite these victories, the Paraguayan forces did not continue to Cuiabá, the capital of the province, where Augusto Leverger had fortified the camp of Melgaço to protect Cuiabá. Their main objective was the capture of the gold and diamond mines, disrupting the flow into Brazil until 1869.[12]:27

The invasion of Corrientes and Rio Grande do Sul was the second phase of the Paraguayan offensive. To raise the support of the Uruguayan Blancos, the Paraguayans had to travel through Argentine territory. In Jan. 1865 López asked the Argentine government's permission for an army of 20,000 men (led by Gen. Wenceslao Robles) to travel through the province of Corrientes.[12]:29-30 Argentine President—Bartolomé Mitre refused Paraguay's request and a similar one from Brazil.[12]:29

On 13 April 1865 a Paraguayan squadron sailed down the Río Paraná and attacked two Argentine ships in the port of Corrientes. Immediately Gen. Robles' troops took the city with 3,000 men, and a cavalry force of 800 arrived the same day. Leaving a force of 1,500 men in the city, Robles advanced southwards along the eastern bank.[12]:30

By invading Corrientes López had hoped to gain the support of the powerful Argentine caudillo Justo José de Urquiza, governor of the provinces of Corrientes and Entre Ríos, who was known to be the chief federalist hostile to Mitre and the government in Buenos Aires.[28] However, Urquiza gave his full support to an Argentine offensive.[12]:31 The forces advanced approximately 200 kilometres (120 mi) south before ultimately ending the offensive in failure.

Along with Robles' troops, a force of 12,000 soldiers under Col. Antonio de la Cruz Estigarriba crossed the Argentine border south of Encarnación in May 1865, driving for Rio Grande do Sul. They traveled down Río Uruguay and took the town of São Borja on June 12. Uruguaiana, to the south, was taken on 6 August with little resistance. The Brazilian reaction was yet to come.[12]:36-37

Brazilian counterattack

Brazil sent an expedition to fight the invaders in Mato Grosso. A column of 2,780 men led by Col. Manuel Pedro Drago left Uberaba in Minas Gerais in April 1865 and arrived at Coxim in December after a difficult march of more than 2,000 kilometres (1,200 mi) through four provinces. However, Paraguay had abandoned Coxim by December. Drago arrived at Miranda in September 1866, and Paraguay had left once again. In January 1867 Col. Carlos de Morais Camisão assumed command of the column, now with only 1,680 men, and decided to invade Paraguayan territory, which he penetrated as far as Laguna. Paraguayan cavalry forced the expedition to retreat.

Despite the efforts of Camisão's troops and the resistance in the region, which succeeded in liberating Corumbá in June 1867, Mato Grosso remained under Paraguayan control. The Brazilians withdrew in April 1868, moving their troops to the main theatre of operations, in the south of Paraguay. Communications in the Río de la Plata basin were solely by river; few roads existed. Whoever controlled the rivers would win the war, so Paraguay had built fortifications on the banks of the lower end of Río Paraguay.

The naval battle of Riachuelo occurred on June 11, 1865. The Brazilian fleet commanded by Adm. Francisco Manoel Barroso da Silva won, destroying the powerful Paraguayan navy and preventing the Paraguayans from permanently occupying Argentine territory. For all practical purposes, the battle decided the outcome of the war in favor of the Triple Alliance; from that point on it controlled the waters of the Río de la Plata basin up to the entrance to Paraguay.[29]

While López ordered the retreat of the forces that occupied Corrientes, the Paraguayan troops that invaded São Borja advanced, taking Itaqui and Uruguaiana. A separate division (3,200 men) that continued towards Uruguay, under the command of Maj. Pedro Duarte, was defeated by Flores in the bloody Battle of Jataí on the banks of the Río Uruguay.

The allied troops united under Pedro II of Brazil, the Count d'Eu and President Mitre in the camp of Concordia, in the Argentine province of Entre Ríos.[12]:39 Field Marshal Manuel Luís Osório was at the front of the Brazilian troops. Some of the troops, commanded by Lt. Gen. Manuel Marques de Sousa, baron of Porto Alegre, left to reinforce Uruguaiana. The Paraguayans yielded and the Siege of Uruguaiana ended on September 18, 1865.[12]:40

In subsequent months the Paraguayans were driven out of the cities of Corrientes and San Cosme, the only Argentine territory still in Paraguayan possession. By the end of 1865 the Triple Alliance was on the offensive. Its armies numbered 42,000 infantry and 15,000 cavalry as they invaded Paraguay in April.[12]:51-52

On September 12, 1866, López invited Mitre and Flores to a conference in Yatayty Cora, which resulted in a "heated argument".[12]:62 He had realized that the war was lost and was ready to sign a peace treaty with the Allies.[30] No agreement was reached, though, since Mitre's conditions for signing the treaty were that every article of the secret Treaty of the Triple Alliance was to be carried out, a condition that López refused.[30] Article 6 of the treaty made truce or peace nearly impossible, as it stipulated that the war was to continue until the then government ceased to be, which meant the death or removal of López.

After the conference the allies marched into Paraguayan territory, reaching the defensive line of Curupayty. Trusting in their numerical superiority and the possibility of attacking the flank of the defensive line through the Paraguay River by using the Brazilian ships, the Allies made a frontal assault on the defensive line, supported by the flank fire of the battleships. However, the Paraguayans, commanded by Gen. José E. Díaz, stood strong in their positions, set up for a defensive battle. They inflicted tremendous damage on the Allied troops. The Battle of Curupayty resulted in an almost catastrophic defeat for the Allied forces, ending their offensive for ten months, until July 1867.[12]:65

Caxias in command

Assuming command on 18 Nov. 1866 of the Brazilian army, Field Marshal Luís Alves de Lima e Silva, Marquis and, later, Duke of Caxias, had landed Corrientes in early November.[12]:68 He found the Brazilian army practically paralyzed, devastated by disease. Gen. Flores had left for Uruguay in Sept. 1866. With the departure of President Mitre in Feb. 1867, Caxias assumed overall command of the Allied force.[12]:65 Tamandaré was replaced in December by Adm. Joaquim José Inácio, future Viscount of Inhaúma. Osório organized a 5,000-strong third corps of the Brazilian army in Rio Grande do Sul.[12]:68

Between November 1866 and July 1867 Caxias organized a health corps (to give aid to the endless number of injured soldiers and to fight the epidemic of cholera) and a system of supply for the troops. Military operations were limited to skirmishing with the Paraguayans and bombarding Curupaity. López took advantage of the disorganization of the enemy to reinforce his stronghold in Humaitá.[12]:70

The march to outflank the left wing of the Paraguayan fortifications constituted the basis of Caxias' tactics. He wanted to bypass the Paraguayan strongholds, cut the connections between Asunción and Humaitá and finally encircle the Paraguayans. To this end he marched to Tuyucê on 22 July 1867. President Mitre returned and assumed overall command on 27 July. The Allied force advanced to San Solano on the 29th and Tayi on 2 Nov., isolating Humaitá from Asunción. López reacted by attacking the rearguard of the allies in the Battle of Tuyutí, but suffered further defeat.[12]:73-78

By December 1867 there were 45,791 Brazilians, 6,000 Argentinians and 500 Uruguayans at the front. President Mitre returned to Argentina on 13 Jan. 1868, following the death by cholera of Vice President Dr. Marcos Paz.[12]:79 Humaitá fell on 25 July 1868, after a long siege.[12]:86

En route to Asunción, Caxias' army went 200 kilometres (120 mi) north to Palmas, stopping at the Piquissiri River. There López had concentrated 12,000 Paraguayans in a fortified line that exploited the terrain and supported the forts of Angostura and Itá-Ibaté. Resigned to frontal combat, Caxias ordered the so-called Piquissiri maneuver. While a squadron attacked Angostura, Caxias made the army cross to the west side of the river. He ordered the construction of a road in the swamps of the Chaco along which the troops advanced to the northeast. At Villeta the army crossed the river again, between Asunción and Piquissiri, behind the fortified Paraguayan line. Instead of advancing to the capital, already evacuated and bombarded, Caxias went south and attacked the Paraguayans from the rear.[12]:89-91

Caxias had won a series of victories in December 1868, capturing Itororó, Lomas Valentinas and Angostura. On 24 December he sent a note to Solano López asking for surrender, but López refused and fled to Cerro Leon.[12]:90-100 Asunción was occupied on January 1, 1869, by Gen. Juan da Souza da Fonseca Costa, father of the future Marshal Hermes da Fonseca. On January 5th Caxias entered the city with the rest of the army, and on the 12th asked to be relieved of his command.[12]:99

End of the war

Command of Count d'Eu

The son-in-law of the Emperor Pedro II, Luís Filipe Gastão de Orléans, Count d'Eu, was nominated to direct the final phase of the military operations in Paraguay. He sought not just a total rout of Paraguay but also the strengthening of the Brazilian Empire. In August 1869 the Triple Alliance installed a provisional government in Asunción headed by Paraguayan Cirilo Antonio Rivarola.

President Solano López organized the resistance in the mountain range northeast of Asunción. At the head of 21,000 men, Count d'Eu led the campaign against the Paraguayan resistance, the Campaign of the Mountain Range, which lasted over a year. The most important battles were the battles of Piribebuy and of Acosta Ñu, in which more than 5,000 Paraguayans died.

Death of López

Two detachments were sent in pursuit of Solano López, who was accompanied by 200 men in the forests in the north. On March 1, 1870, the troops of Gen. José Antônio Correia da Câmara surprised the last Paraguayan camp in Cerro Corá. During the ensuing battle, López was wounded and separated from the remainder of his army. Too weak to walk, he was escorted by his aide and a pair of officers, who led him to the banks of the Aquidaban-nigui River. The officers left López and his aide there while they looked for reinforcements. Before they returned, Gen. Câmara arrived with a small number of soldiers. Though he offered to permit López to surrender and guaranteed his life, López refused. Shouting "¡Muero con mi patria!" ("I die with my homeland!"), he tried to attack Câmara with his sword. He was quickly killed by Câmara's men, bringing an end to the long conflict.[31]

Casualties

At the end of the war, with Paraguay suffering severe shortages of weapons and supplies, López reacted with draconian attempts to keep order, ordering troops to kill any of their colleagues, including officers, who talked of surrender.[32] Paranoia prevailed in the army, and soldiers fought to the bitter end in a resistance movement, resulting in more destruction in the country.[32]

Paraguay suffered massive casualties, and the war's disruption and disease also cost civilian lives. Some historians estimate the nation lost the majority of its population. The specific numbers are hotly disputed and range widely. A survey of 14 estimates of Paraguay's pre-war population varied between 300,000 and 1,337,000.[33] Because of the local situation, all casualty figures are a very rough estimate; accurate casualty numbers may never be determined.

The worst reports are that up to 90% of the male population was killed, though this figure is without support.[32] One estimate places total Paraguayan losses--through both war and disease--as high as 1.2 million people, or 90% of its pre-war population.[34] A different estimate places Paraguayan deaths at approximately 300,000 people out of 500,000 to 525,000 pre-war inhabitants.[35] During the war, many men and boys fled to the countryside and forests. After the war an 1871 census recorded 221,079 inhabitants, of which 106,254 were female, 28,746 were male, and 86,079 were children (with no indication of sex or upper age limit).[36]

A 1999 study by Thomas Whigham from the University of Georgia (published in the Latin American Research Review under the title "The Paraguayan Rosetta Stone: New Evidence on the Demographics of the Paraguayan War, 1864–1870", and later expanded in the 2002 essay titled "Refining the Numbers: A Response to Reber and Kleinpenning") has a methodology to yield more accurate figures. To establish the population before the war, Whigham used an 1846 census and calculated, based on a population growth rate of 1.7% to 2.5% annually (which was the standard rate at that time), that the immediately pre-war Paraguayan population in 1864 was approximately 420,000–450,000. Based on a census carried out after the war ended, in 1870-1871, Whigham concluded that 150,000–160,000 Paraguayan people had survived, of whom only 28,000 were adult males. In total, 60%-70% of the population died as a result of the war,[37] leaving a woman/man ratio of 4 to 1 (as high as 20 to 1, in the most devastated areas).[37]

Of approximately 123,000 Brazilians who fought in the Paraguayan War, the best estimates are around 50,000 men died. Uruguay had about 5,600 men under arms (including some foreigners), of whom about 3,100 died.

The high rates of mortality were not all due to combat. As was common before antibiotics were developed, disease caused more deaths than war wounds. Bad food and poor sanitation contributed to disease among troops and civilians. Many deaths are believed to have been caused by cholera. Among the Brazilians, two-thirds of the dead died either in a hospital or on the march. At the beginning of the conflict, most Brazilian soldiers came from the north and northeast regions; the change from a hot to a colder climate, combined with restricted food rations, may have weakened their resistance. Entire battalions of Brazilians were recorded as dying after drinking water from rivers. Therefore, some historians believe cholera, transmitted in the water, was a leading cause of death during the war.

A death of over 60% of the Paraguayan population makes this war proportionally one of the most destructive in modern times for a nation state.[38]

Consequences of the war

During the war the Brazilian army took complete control of Paraguayan territory and occupied the country for six years after the final defeat in 1870. In part this was to prevent the annexation of even more territory by Argentina, which had wanted to seize the entire Chaco region. During this time, Brazil and Argentina had strong tensions, with the threat of armed conflict between them.

During the wartime sacking of Asunción, Brazilian soldiers carried off war trophies. Among the spoils taken was the "Christian" cannon, named because it was cast from church bells of Asunción melted down for the war. In addition, officials ordered that the Paraguayan national archives be packed up and transferred to the National library in Rio de Janeiro. They have been held virtually unavailable to research by scholars.[39]

Results:[40]

- Paraguay suffered the downfall of its government, loss of territories and huge population losses and property damage. These resulted in an economic crisis. For years after the war, Paraguayan development was slow. Some sources claim it lost nearly 69% of the population, but recent study claims it was nearer 30%.

- In Brazil the war exposed the fragility of the Empire, and dissociated the monarchy with the army. The Brazilian army became a new and influential force in national life. It developed as a strong national institution that, with the war, gained tradition and internal cohesion. The Army would take a significant role in the later development of the history of the country. Nearly 50,000 deaths resulted, most by sickness and the harsh climate.

As in other countries, "wartime recruitment of slaves in the Americas rarely implied a complete rejection of slavery and usually acknowledged masters' rights over their property." [41] Brazil compensated owners who freed slaves for the purpose of fighting in the war, on the condition that the freedmen immediately enlist. It also impressed slaves from owners when needing manpower, and paid compensation. In areas near the conflict, slaves took advantage of wartime conditions to escape, and some fugitive slaves volunteered for the army. Together these effects undermined the institution of slavery. But, the military also upheld owners' property rights, as it returned at least 36 fugitive slaves to owners who could satisfy its requirement for legal proof. Significantly, slavery was not officially ended until the early 1880s.[41]

The economic depression and the strengthening of the army later played a large role in the deposition of the emperor Pedro II and the republican proclamation in 1889. Gen. Deodoro da Fonseca became the first Brazilian president.

Brazil spent close to 614 thousand réis (the Brazilian currency at the time), which were gained from the following sources:

| réis, thousands | source |

|---|---|

| 49 | Foreign loans |

| 27 | Domestic loans |

| 102 | Paper emission |

| 171 | Title emission |

| 265 | Taxes |

Due to the war, Brazil ran a deficit between 1870 and 1880, which was finally paid off. At the time foreign loans were not significant sources of funds.[40]

- Following the war, Argentina faced many federalist revolts against the national government. Economically it benefitted from having sold supplies to the Brazilian army, but the war overall decreased the national treasure. The national action contributed to the consolidation of the centralized government after revolutions were put down, and the growth in influence of Army leadership. It resulted in nearly 30,000 deaths.

- Uruguay had lesser effects, although it suffered the deaths of nearly 5,000 soldiers.

Interpretation of the causes of the war and its aftermath has been a controversial topic in the histories of participating countries, especially in Paraguay. There it has been considered either a fearless struggle for the rights of a smaller nation against the aggressions of more powerful neighbors, or a foolish attempt to fight an unwinnable war that almost destroyed the nation. People of Argentina have their own internal disputes over interpretations of the war: many Argentinians think the conflict was Mitre's war of conquest, and not a response to aggression. They note that Mitre used the Argentine Navy to deny access to the Río de la Plata to Brazilian ships in early 1865, thus starting the war. People in Argentina note that Solano López, mistakenly believing he would have Mitre's support, had seized the chance to attack Brazil at that time.

In Brazil many have believed that the United Kingdom financed the allies against Paraguay, and that British imperialism was the catalyst for the war. The academic consensus is that no evidence supports this thesis. From 1863-65 Brazil and the UK had an extended diplomatic crisis and, five months after the war started, cut off relations. In 1864 a British diplomat sent a letter to Solano López asking him to avoid hostilities in the region. There is no evidence that Britain forced the allies to attack Paraguay.

In December 1975, after presidents Ernesto Geisel and Alfredo Stroessner signed a treaty of friendship and co-operation[42] in Asunción, the Brazilian government returned some of its spoils of war to Paraguay, but has kept others. In April 2013 Paraguay renewed demands for the return of the "Christian" cannon. Brasil has had this on display at the former military garrison, now used as the National History Museum, and says that it is part of its history as well.[39]

Territorial changes and treaties

Following Paraguay's defeat in 1870, Argentina sought to enforce one of the secret clauses of the Triple Alliance Treaty, which would have permitted it to annex a large portion of the Gran Chaco region. This area was rich in quebracho wood (a product used in the tanning of leather). The Argentine negotiators proposed to Brazil that Paraguay be divided in two, with each of the victors incorporating half into its territory. The Brazilian government, however, wanted to maintain Paraguay as a buffer with Argentina. Accordingly, it rejected the Argentine proposal to annex Paraguay in its entirety.

Eventually the post-war border between Paraguay and Argentina was resolved through long negotiations, completed February 3, 1876. This treaty granted Argentina roughly a third of the area it had originally desired. Argentina became the strongest of the River Plate countries. During the campaign, the provinces of Entre Ríos and Corrientes had supplied Brazilian troops with cattle, foodstuffs, and other products.

When the two parties could not reach consensus on the fate of the area between the Río Verde and the main branch of Río Pilcomayo, US President Rutherford B. Hayes was asked to arbitrate. He declared it should remain part of Paraguay, for which the Paraguayan department Presidente Hayes was named in his honour.[43]

Brazil signed a separate peace treaty with Paraguay on January 9, 1872, in which it obtained freedom of navigation on the Río Paraguay. Brazil also retained the borders it had claimed before the war.[44]

In total, Argentina and Brazil annexed about 140,000 square kilometers (54,054 sq mi) of Paraguayan territory: Argentina took much of the Misiones region and part of the Chaco between the Bermejo and Pilcomayo rivers, an area that today constitutes the province of Formosa. Brazil enlarged its Mato Grosso province by claiming territories whose control had been disputed with Paraguay before the war. Both demanded a large indemnity, which Paraguay paid for the next century. This hobbled its development. In 1943, after Paraguay had paid nearly all of the indemnity to Brazil, the latter's president Getúlio Vargas cancelled the remainder of the debt.

Meanwhile, the Colorados gained political control of Uruguay and retained it until 1958.

Effects on yerba mate industry

Since colonial times, yerba mate had been a major cash crop for Paraguay. Until the war, it had generated significant revenues for the country. The war caused a sharp drop in harvesting of yerba mate in Paraguay, reportedly by as much as 95% between 1865 and 1867.[45] Soldiers from all sides used yerba mate to diminish hunger pains and alleviate combat anxiety.[46]

After the war concluded in 1870, Paraguay was ruined economically and by population losses. Much of the 156,415 square kilometers (60,392 sq mi) lost by Paraguay to Argentina and Brazil was rich in yerba mate, so by the end of the 19th century, Brazil became the leading producer of the crop.[46] Foreign entrepreneurs entered the Paraguayan market and took control of its remaining yerba mate production and industry.[45]

Media depictions

Novels

- Carlos de Oliveira Gomes, A Solidão Segundo Solano López, Civilização Brasileira, 1980;[47] Círculo do Livro, 1982.

- Joseph Eskenazi Pernidji and Mauricio Eskenazi e Pernidji. Homens e Mulheres na Guerra do Paraguai. Imago, 2003.

- Lily Tuck. The News From Paraguay. Harper Perennial, 2004.

- DORATIOTO, Francisco. Maldita guerra. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2002.

Films

- Argentino hasta la muerte, by Fernando Ayala, Argentina (1971).

- Cerro Cora, by Guillermo Vera, Paraguay (1978).

- Netto perde sua alma, by Beto Souza and Tabajara Ruas, Brazil (2001).

- Guerra do Brasil, documentary by Sylvio Back, Brazil (1987).

- Cándido López - Los campos de batalla, documentary by José Luis García, Argentina (2005).

- The Paraguayan War, documentary by Denis Wright, Brazil (2009).

See also

- List of Wars involving Brazil

- List of battles of the Paraguayan War

- Paraguayan War casualties

- Treaty of the Triple Alliance

- Fortress of Humaitá

- Women in the Paraguayan War

Endnotes

Footnotes

- ↑ Testimonios de la Guerra Grande y Muerte del Mariscal López by Julio César Frutos

- ↑ Ñorairõ Guasu, 1864 guive 1870 peve by Guido Rodríguez Alcalá. Secretaría Nacional de Cultura, 28 May 2011 (Spanish)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Kraay, Hendrik; Whigham, Thomas L. (2004). "I die with my country:" Perspectives on the Paraguayan War, 1864–1870. Dexter, Michigan: Thomson-Shore. ISBN 978-0-8032-2762-0, p. 16 Quote: "During the 1960s, revisionists influenced by both left-wing dependency theory and, paradoxically, an older, right-wing nationalism (especially in Argentina) focused on Britain’s role in the region. They saw the war as a plot hatched in London to open up a supposedly wealthy Paraguay to the international economy. With more enthusiasm than evidence revisionists presented the loans contracted in London by Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil as proof of the insidious role of foreign capital... Little evidence for these allegations about Britain’s role has emerged, and the one serious study to analyze this question has found nothing in the documentary base to confirm the revisionist claim."

- ↑ Miguel Angel Centeno, Blood and Debt: War and the Nation-State in Latin America, University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1957. Page 55.

- ↑ Historia de las relaciones exteriores de la República Argentina (notes from CEMA University, in Spanish, and references therein)

- ↑ Historical Statistics of the World Economy: 1-2008 AD by Angus Maddison

- ↑ Scheina 2003, p. 331.

- ↑ PJ O'Rourke, Give War a Chance, New York: Vintage Books, 1992. Page 47.

- ↑ "Carlos Antonio López", Library of Congress Country Studies, December 1988. URL accessed December 30, 2005.

- ↑ Page 630 from The Encyclopedia of World History Sixth Edition, Peter N. Stearns (general editor), © 2001 The Houghton Mifflin Company, at Bartleby.com.

- ↑ Robert Cowley, The Reader's Encyclopedia to Military History. New York, New York: Houston Mifflin, 1996. Page 479.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 12.8 12.9 12.10 12.11 12.12 12.13 12.14 12.15 12.16 12.17 12.18 12.19 12.20 12.21 12.22 12.23 12.24 12.25 12.26 12.27 12.28 12.29 12.30 12.31 12.32 12.33 12.34 12.35 Hooker, T.D., 2008, The Paraguayan War, Nottingham: Foundry Books, ISBN 1901543153

- ↑ Whigham 2002, p. 118.

- ↑ Scheina 2003, pp. 313–4.

- ↑ Scheina 2003, p. 314.

- ↑ Galeano, Eduardo. "Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent," Monthly Review Press, 1997

- ↑ Chiavenatto,Julio José. Genocídio Americano: A Guerra do Paraguai, Editora Brasiliense, SP. Brasil, 1979

- ↑ Historia General de las relaciones internacionales de la República Argentina (Spanish)

- ↑ Salles 2003, p. 14.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Historia General de las relaciones internacionales de la República Argentina(Spanish)

- ↑ "TRATADO DE LAS PUNTAS DEL ROSARIO (Guerra del Paraguay)", La Gazeta (Spanish)

- ↑ Scheina 2003, p. 313.

- ↑ Scheina 2003, pp. 315–7.

- ↑ Salles 2003, p. 18.

- ↑ Scheina 2003, p. 318.

- ↑ Wilson 2004, p. .

- ↑ Salles 2003, p. 38.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Scheina 2003, p. 319.

- ↑ Scheina 2003, p. 320.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Vasconsellos 1970, p. 108.

- ↑ Bareiro, p. 90.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Shaw 2005, p. 30.

- ↑ see F. Chartrain : "L'Eglise et les partis dans la vie politique du Paraguay depuis l'Indépendance", Paris I University, "Doctorat d'Etat", 1972, pp. 134–135

- ↑ Byron Farwell, The Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Land Warfare: An Illustrated World View, New York: WW Norton, 2001. p. 824.

- ↑ Jürg Meister, Francisco Solano López Nationalheld oder Kriegsverbrecher?, Osnabrück: Biblio Verlag, 1987. 345, 355, 454–5. ISBN 3-7648-1491-8

- ↑ An early 20th-century estimate is that from a prewar population of 1,337,437, the population fell to 221,709 (28,746 men, 106,254 women, 86,079 children) by the end of the war (War and the Breed, David Starr Jordan, p. 164. Boston, 1915; Applied Genetics, Paul Popenoe, New York: Macmillan Company, 1918)

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 "Holocausto paraguayo en Guerra del ’70". abc accessdate=2009-10-26.

- ↑ Pinker, Steven (2011). Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-312201-2. Steven Pinker

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Isabel Fleck, "Paraguai exige do Brasil a volta do "Cristão", trazido como troféu de guerra" (Paraguay has demanded Brazil return the "Christian", taken as a war trophy), Folha de S. Paulo, 18 April 2013, accessed 1 July 2013

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 DORATIOTO, Francisco, Maldita Guerra, Companhia das Letras, 2002

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Kraay, Hendrik (1996). "'The Shelter of the Uniform': The Brazilian Army and Runaway Slaves, 1800–1888". Journal of Social History 29 (3): 637–657. doi:10.1353/jsh/29.3.637. JSTOR 3788949.

- ↑ "Treaty of friendship and co-operation 4 December 1975" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-05-10.

- ↑ http://www.npr.org/blogs/parallels/2014/10/30/360126710/the-place-where-rutherford-b-hayes-is-a-really-big-deal

- ↑ Vasconsellos 1970, pp. 78, 110–114.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Blinn Reber, Vera. Yerba Mate in Nineteenth Century Paraguay, 1985.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Folch, Christine (2010). "Stimulating Consumption: Yerba Mate Myths, Markets, and Meanings from Conquest to Present". Comparative Studies in Society and History 52 (1): 6–36. doi:10.1017/S0010417509990314.

- ↑ gojaba.com

References

- Hooker, Terry D. (2008). The Paraguayan War. Nottingham: Foundry Books. ISBN 1-901543-15-3.

- Kolinski, Charles J. (1965). Independence or Death! The story of the Paraguayan War. Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida Press.

- Kraay, Hendrik; Whigham, Thomas L. (2004). I Die with My Country: Perspectives on the Paraguayan War, 1864–1870. Dexter, Michigan: Thomson-Shore. ISBN 978-0-8032-2762-0.

- Leuchars, Chris (2002). To the Bitter End: Paraguay and the War of the Triple Alliance. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-32365-8.

- Whigham, Thomas L. (2002). The Paraguayan War: Causes and Early Conduct 1. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-4786-4.

- Box, Pelham Horton (1967). The origins of the Paraguayan War. New York: Russel & Russel.

- Abente, Diego (1987). "The War of the Triple Alliance". Latin American Research Review 22 (2): 47–69.

- Bareiro, Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Encyclopædia Britannica. http://search.eb.com/eb/article-9058388

- Hardy, Osgood (Oct 1919). "South American Alliances: Some Political and Geographical Considerations". Geographical Review 8 (4/5): 259–265. doi:10.2307/207840.

- Leuchars, Chris (2002). To the Bitter End: Paraguay and the War of the Triple Alliance. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press.

- Peñalba, José Alfredo Fornos (Apr 1982). "Draft Dodgers, War Resisters and Turbulent Gauchos: The War of the Triple Alliance against Paraguay". The Americas 38 (4): 463–479. doi:10.2307/981208. JSTOR 981208.

- Salles, Ricardo (2003). Guerra do Paraguai: Memórias & Imagens (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Bibilioteca Nacional.

- Scheina, Robert (2003). Latin America's Wars: The Age of the Caudillo, 1791–1899. Dulles, Virginia: Brassey's.

- Shaw, Karl (2005) [2004]. Power Mad! [Šílenství mocných] (in Czech). Praha: Metafora. ISBN 978-80-7359-002-4.

- Vasconsellos, Victor N. (1970). Resumen de Historia del Paraguay. Delimitaciones Territoriales. Asunción, Paraguay: Industria Grafica Comuneros.

- Whigham, Thomas (2002). The Paraguayan War. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press.

- Williams, John Hoyt (April 2000). "The Battle of Tuyuti". Military History 17 (1): 58.

- Wilson, Peter (May 2004). "Latin America's Total War". History Today 54 (5). ISSN 0018-2753.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paraguayan War. |

- Campanha do Paraguay : commando em chefe de S. A. o Sr. Marechal de Exercito, Conde d'Eu – Official Report of the Empire of Brazil 1869 -(Portuguese)

- Paraguay: War of the Triple Alliance, 1988, Country Studies, US Library of Congress

- The War of Paraguay, Brasil Escola website (Portuguese)

- "The War of Paraguay", História do Brasil, 2004-2011, Sua Pesquisa.com website (Portuguese)

- 'Paraguay de Antes' (old photos & pics) (Spanish)

- Cerro Corá in Google Maps

- Gary Brecher, "Paraguay: A Brief History Of National Suicide", The Exile, 26 December 2007

- Timeline of the War of the Triple Alliance, Website on the war

- Ulysses Narciso, "War of the Triple Alliance", The South American Military History Webpage, personal website at GeoCities

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Library of Congress Country Studies.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Library of Congress Country Studies.

.svg.png)