Papaya

Papaya output in 2005, shown as a percentage of the top producer, Brazil (1.7 megatonnes) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The papaya (/pəˈpaɪə/ or US /pəˈpɑːjə/) (from Carib via Spanish), papaw, (/pəˈpɔː/[2]) or pawpaw (/ˈpɔːˌpɔː/[2] is the fruit of the plant Carica papaya, and is one of the 22 accepted species in the genus Carica of the plant family Caricaceae.[3] It is native to the tropics of the Americas, perhaps from southern Mexico and neighbouring Central America.[4] It was first cultivated in Mexico several centuries before the emergence of the Mesoamerican classical civilizations.

The papaya is a large, tree-like plant, with a single stem growing from 5 to 10 m (16 to 33 ft) tall, with spirally arranged leaves confined to the top of the trunk. The lower trunk is conspicuously scarred where leaves and fruit were borne. The leaves are large, 50–70 cm (20–28 in) in diameter, deeply palmately lobed, with seven lobes. Unusually for such large plants, the trees are dioecious. The tree is usually unbranched, unless lopped. The flowers are similar in shape to the flowers of the Plumeria, but are much smaller and wax-like. They appear on the axils of the leaves, maturing into large fruit - 15–45 cm (5.9–17.7 in) long and 10–30 cm (3.9–11.8 in) in diameter. The fruit is ripe when it feels soft (as soft as a ripe avocado or a bit softer) and its skin has attained an amber to orange hue.

Carica papaya was the first transgenic fruit tree to have its genome deciphered.[5]

Distribution

Carica papaya is native to the New World in Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, French Guiana, Guatemala, Guyana, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Suriname, Venezuela, and northern Argentina. C. papaya has become naturalized in the Bahamas, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Grenada, Guadeloupe, Haiti, Jamaica, Martinique, Puerto Rico, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Trinidad and Tobago, the U.S. Virgin Islands, the U.S. state of Florida, and Malawi and Tanzania in Africa. Additional crops of C. papaya are grown in India, Australia, the Philippines, and the U.S. state of Hawaii.[1]

Cultivation

Papaya plants come in three sexes: "male," "female," and "hermaphrodite." The male produces only pollen, never fruit. The female will produce small, inedible fruits unless pollinated. The hermaphrodite can self-pollinate since its flowers contain both male stamens and female ovaries. Almost all commercial papaya orchards contain only hermaphrodites.[6]

Gaining in popularity among tropical fruits worldwide, papaya is now ranked third with 11.22 Mt, or 15.36 percent of the total tropical fruit production,[note 1] behind mango with 38.6 Mt (52.86%) and pineapple with 19.41 Mt (26.58%). Global papaya production has grown significantly over the last few years, mainly as a result of increased production in India.[7] Papaya has become an important agricultural export for developing countries, where export revenues of the fruit provide a livelihood for thousands of people, especially in Asia and Latin America. Papaya exports contribute to the growing supply of healthful food products on international markets. The top three exporting countries accounted for 63.28 percent of the total global exports of papaya between 2007 and 2009, with more than half of those exports going to the United States.

Global papaya production is highly concentrated, with the top ten countries averaging 86.32 percent of the total production for the period 2008–2010. India is the leading papaya producer, with a 38.61 percent share of the world production during 2008–2010, followed by Brazil (17.5%) and Indonesia (6.89%). Other important papaya producing countries and their share of global production include Nigeria (6.79%), Mexico (6.18%), Ethiopia (2.34%), Democratic Republic of the Congo (2.12%), Colombia (2.08%), Thailand (1.95%), and Guatemala (1.85%).

Originally from southern Mexico (particularly Chiapas and Veracruz), Central America, and northern South America, the papaya is now cultivated in most tropical countries. In cultivation, it grows rapidly, fruiting within three years. It is, however, highly frost-sensitive, limiting its production to tropical climates. Temperatures below −2 °C (29 °F) are greatly harmful if not fatal. In Florida and California, growth is generally limited to southern parts of the states. In California, it's generally limited to private gardens in Los Angeles, Orange, and San Diego counties. It also prefers sandy, well-drained soil as standing water will kill the plant within 24 hours.[8]

For cultivation, however, only female plants are used, since they give off a single flower each time, and close to the base of the plant, while the male gives off multiple flowers in long stems, which result in poorer quality fruit.

Diseases and Pests

Viruses

Papaya ringspot virus is a well-known virus within plants in Florida. The first signs of the virus are yellowing and vein-clearing of younger leaves as well as mottling yellow leaves. Infected leaves may obtain blisters, roughen or narrow, with blades sticking upwards from the middle of the leaves. The petioles and stems may develop dark green greasy streaks and in time become shorter. The ringspots are circular, C-shaped markings that are darker green than the fruit itself. In the later stages of the virus, the markings may become gray and crusty. Viral infections impact growth and reduce the fruit's quality. One of the biggest effects that viral infections have on papaya is the taste. As of 2010, the only way to protect papaya from this virus is genetic modification.[9]

The papaya mosaic virus is very destructive because it completely destroys the plant until only a small tuft of leaves are left. The virus affects both the leaves of the plant and also the fruit itself. Leaves show thin, irregular, dark-green lines around the borders and clear areas around the veins. The more severely affected leaves are irregular and linear in shape. The virus can infect the fruit at any stage of its maturity. Fruits as young as 2 weeks old have been spotted with dark-green ringspots about 1 inch in diameter. Rings on the fruit are most likely seen on either the stem end or the blossom end. In the early stages of the ringspots, the rings tend to be many closed circles, but as the disease develops the rings will increase in diameter consisting of one large ring. The difference between the ringspot and the mosaic viruses is the ripe fruit in the ringspot has mottling of colors and mosaic does not.[10]

Fungi

The fungus Anthracnose is known to specifically attack papaya especially the mature fruits. The disease starts out small with very few signs, such as water-soaked spots on ripening fruits. The spots become sunken, turn brown or black and may get bigger. In some of the older spots, the fungus may produce pink spores. The fruit ends up being soft and having an off flavor because the fungus grows into the fruit.[11]

The fungus powdery mildew occurs as a superficial white presence on the surface of the leaf in which it is easily recognized. Tiny, light yellow spots begin on the lower surfaces of the leaf as the disease starts to make its way. The spots enlarge and white powdery growth appears on the leaves. The infection usually appears at the upper leaf surface as white fungal growth. Powdery Mildew is not as severe as other diseases.[12]

The fungus phythphthora blight causes damping-off, root rot, stem rot, stem girdling and fruit rot. Damping-off happens in very young plants by wilting and death in plant. The spots on established plants start out as water-soaked lesions at the fruit and branch scars. These spots can get bigger and cause the death of the plant. The roots can be severely and rapidly infected, causing the plant to rapidly brown and wilt away collapsing within days. The most dangerous feature of the disease is the infection of the fruit because it cause harm to people who consume it. The biggest evidence that the fungus is present are the water-soaked marks that appears first along with the white fungus that grows on the dead fruit. After the fruit dies it shrivels and falls to the ground.[11]

Pests

The papaya fruit fly is mainly yellow with black marks. The female papaya fruit fly has a very long, slender abdomen with an extended ovipositor that exceeds the length of its body. The male papaya fruit fly looks like the female with the differences of a hairy abdomen and no ovipositor. Long slender eggs are laid inside of the fruit by the female papaya fruit fly. The larva are white and look very much like the regular fruit fly larvae. The female is capable of laying up to 100 or more eggs and are laid during the evening or early morning in groups of ten inside young fruit. They usually hatch within 12 days of being in the fruit where they’ll feed on the seeds and interior parts of the fruit. When the larvae matures (usually 16 days after being hatched) they eat their way out of the fruit, drop to the ground, and pupate just below the soil and emerge within one to two weeks as mature flies. The flesh of the papaya must be ripe in order for the fly to migrate towards the surface of the fruit because unripe papaya juice is fatal to them. The papaya will turn yellow and drop to the ground if it is infected by the papaya fruit fly.[11]

The two-spotted spider mite is a 0.5 mm long brown or orange-red but a green, greenish yellow translucent oval pest. They all have needle-like piercing-sucking mouthparts and feed by piercing the plant tissue with their mouth parts usually the underside of the plant. The spider mites spin fine threads of webbing on the host plant and when they remove the sap, the mesophyll tissue collapses and a small chlorotic spot forms at the feeding sites. The leaves of the papaya fruit turn yellow, gray or bronze. If the spider mites aren’t controlled it can cause the death of the fruit.[11]

The papaya whitefly lays yellow oval eggs that appear dusted on the undersides of the leaves. They eat the papaya fruits leaves therefore damaging the fruit. There, the eggs developed into flies in three stages called instars. The first instar has well-developed legs and is the only mobile immature life stage. The crawlers insert their mouthparts in the lower surfaces of the leaf when they find it suitable and usually don’t move again in this stage. The next instars are flattened, oval and scale-like. In the final stage as the pupal the whiteflies are more convex, with large conspicuous red eyes.[11]

Cultivars

Two kinds of papayas are commonly grown. One has sweet, red or orange flesh, and the other has yellow flesh; in Australia, these are called "red papaya" and "yellow papaw", respectively.[13] Either kind, picked green, is called a "green papaya."

The large-fruited, red-fleshed 'Maradol', 'Sunrise', and 'Caribbean Red' papayas often sold in US markets are commonly grown in Mexico and Belize.[14]

In 2011 Philippine researchers reported that by hybridizing papaya with Vasconcellea quercifolia they had developed conventionally bred, nongenetically engineered papaya resistant to PRV.[15]

Genetically engineered cultivars

In response to the papaya ringspot virus (PRV) outbreak in Hawaii, in 1998 genetically altered papaya were approved and brought to market (including 'SunUp' and 'Rainbow' varieties.) Resistant varieties have some PRV DNA incorporated into the DNA of the plant are resistant to PRVs.[16][17] As of 2010, 80% of Hawaiian papaya plants were genetically modified. The modifications were made by University of Hawaii scientists who made the modified seeds available to farmers without charge.[18][19]

Uses

Papayas can be used as a food, a cooking aid and in traditional medicine. The stem and bark may be used in rope production.

Meat tenderizing

Both green papaya fruit and the tree's latex are rich in papain, a protease used for tenderizing meat and other proteins. Its ability to break down tough meat fibers was used for thousands of years by indigenous Americans. It is now included as a component in powdered meat tenderizers.

Nutrients, phytochemicals and culinary practices

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 179 kJ (43 kcal) |

|

10.82 g | |

| Sugars | 7.82 g |

| Dietary fiber | 1.7 g |

|

0.26 g | |

|

0.47 g | |

| Vitamins | |

| Vitamin A equiv. beta-carotene |

(6%) 47 μg (3%) 274 μg89 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) |

(2%) 0.023 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) |

(2%) 0.027 mg |

| Niacin (B3) |

(2%) 0.357 mg |

|

(4%) 0.191 mg | |

| Folate (B9) |

(10%) 38 μg |

| Vitamin C |

(75%) 62 mg |

| Vitamin E |

(2%) 0.3 mg |

| Vitamin K |

(2%) 2.6 μg |

| Trace metals | |

| Calcium |

(2%) 20 mg |

| Iron |

(2%) 0.25 mg |

| Magnesium |

(6%) 21 mg |

| Manganese |

(2%) 0.04 mg |

| Phosphorus |

(1%) 10 mg |

| Potassium |

(4%) 182 mg |

| Sodium |

(1%) 8 mg |

| Zinc |

(1%) 0.08 mg |

| Other constituents | |

| Lycopene | 1828 µg |

|

| |

| |

|

Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

Papaya fruit is a significant source of vitamin C and folate, but otherwise has generally low content of nutrients (right table). Papaya skin, pulp and seeds also contain a variety of phytochemicals, including carotenoids and polyphenols.[20]

The ripe fruit of the papaya is usually eaten raw, without skin or seeds. The unripe green fruit can be eaten cooked, usually in curries, salads, and stews. Green papaya is used in Southeast Asian cooking, both raw and cooked.[21] In Thai cuisine, papaya is used to make Thai salads such as som tam and Thai curries such as kaeng som when still not fully ripe. In Indonesian cuisine, the unripe green fruits and young leaves are boiled for use as part of lalab salad, while the flower buds are sautéed and stir-fried with chillies and green tomatoes as Minahasan papaya flower vegetable dish. Papayas have a relatively high amount of pectin, which can be used to make jellies. The smell of ripe, fresh papaya flesh can strike some people as unpleasant. In Brazil, the unripe fruits are often used to make sweets or preserves.

The black seeds of the papaya are edible and have a sharp, spicy taste. They are sometimes ground and used as a substitute for black pepper.

In some parts of Asia, the young leaves of the papaya are steamed and eaten like spinach.

Traditional medicine

In some parts of the world, papaya leaves are made into tea as a treatment for malaria. Antimalarial and antiplasmodial activity has been noted in some preparations of the plant, but the mechanism is not understood and no treatment method based on these results has been scientifically proven.[22]

In the belief that it can raise platelet levels in blood, papaya may be used as a medicine for dengue fever.[23] Papaya is marketed in tablet form to remedy digestive problems.

Papain is also applied topically for the treatment of cuts, rashes, stings and burns. Papain ointment is commonly made from fermented papaya flesh, and is applied as a gel-like paste. Harrison Ford was treated for a ruptured disc incurred during filming of Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom by papain injections.[24]

Preliminary research

Laboratory studies have shown that papaya seeds have contraceptive effects in adult male langur monkeys, and possibly in adult male humans.[25] Phytochemicals in papaya may suppress the effects of progesterone.[26]

Papaya juice has an in vitro antiproliferative effect on liver cancer cells, possibly due to lycopene[27] or immune system stimulation.[28] Papaya seeds might contain antibacterial properties against Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus or Salmonella typhi.[29]

Allergies and side effects

Papaya releases a latex fluid when not quite ripe, which can cause irritation and provoke allergic reaction in some people.

The latex concentration of unripe papayas is speculated to cause uterine contractions, which may lead to a miscarriage. Papaya seed extracts in large doses have a contraceptive effect on rats and monkeys, but in small doses have no effect on the unborn animals.

Excessive consumption of papaya can cause carotenemia, the yellowing of soles and palms, which is otherwise harmless. However, a very large dose would need to be consumed; papaya contains about 6% of the level of beta carotene found in carrots (the most common cause of carotenemia).[30]

Gallery

-

Female flowers

-

Male flowers

-

Leaf

-

Unripe fruit

-

Ripe fruit

-

Unripe fruit

-

Yellow Papaya

-

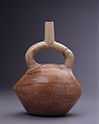

Papaya, Moche culture, Larco Museum Collection The Moche often depicted papayas in their ceramics.[1]

- ^ Berrin, Katherine & Larco Museum. The Spirit of Ancient Peru:Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1997.

See also

- Asimina triloba, pawpaw (of North America)

- Chaenomeles speciosa, flowering quince, which, like Carica papaya, is known as mugua (木瓜) in Chinese

- Papaya salad

- Pseudocydonia, Chinese quince, known as mugua (木瓜) in Chinese

Notes

- ↑ Except bananas and citrus fruits.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Carica papaya was originally described and published in Species Plantarum 2:1036. 1753. GRIN (9 May 2011). "Carica papaya information from NPGS/GRIN". Taxonomy for Plants. National Germplasm Resources Laboratory, Beltsville, Maryland: USDA, ARS, National Genetic Resources Program. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Papaw". Collins Dictionary. n.d. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ↑ "Carica". 2013.

- ↑ "Papaya". purdue.edu.

- ↑ "Scientists decipher fruit tree genome for the first time". ugr.es.

- ↑ C. L. Chia and Richard M. Manshardt, (2001). "Why Some Papaya Plants Fail to Fruit" (PDF). Department of Tropical Plant and Soil Sciences. Retrieved April 2015.

- ↑ "An Overview of Global Papaya Production, Trade, and Consumption". Electronic Data Information Source, University of Florida. Retrieved 2014-02-07.

- ↑ Boning, Charles R. (2006). Florida's Best Fruiting Plants: Native and Exotic Trees, Shrubs, and Vines. Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press, Inc. pp. 166–167.

- ↑ Gonsalves, D., S. Tripathi, J. B. Carr, and J. Y. Suzuki (2010). "Papaya ringspot virus".

- ↑ Hine, B.R.; Holtsmann, O.V.; Raabe, R.D. (July 1965). "Disease of papaya in Hawaii" (PDF).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Mossler, M.A.; Crane, J. date= September 2002. "Florida crop/pest management profile: papaya" (PDF).

- ↑ Cunningham, B. & Nelson, S. (2012, June). "Powdery mildew of papaya in Hawaii" (PDF).

- ↑ "Papaya Vs Papaw". News (15 April 2005). Horticulture Australia. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- ↑ Sagon, Candy (13 October 2004). "Maradol Papaya". Market Watch (13 Oct 2004) (The Washington Post). Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ↑ "Euphytica, Volume 181, Number 2". SpringerLink. doi:10.1007/s10681-011-0388-z. Retrieved 2012-06-29.

- ↑ Genetically Altered Papayas Save the Harvest

- ↑ "Hawaiipapaya.com". Hawaiipapaya.com. Retrieved 2013-06-15.

- ↑ Ronald, Pamela and McWilliams, James (14 May 2010) Genetically Engineered Distortions The New York Times, accessed 1 October 2012

- ↑

- ↑ Rivera-Pastrana DM, Yahia EM, González-Aguilar GA (2010). "Phenolic and carotenoid profiles of papaya fruit (Carica papaya L.) and their contents under low temperature storage". J Sci Food Agric 90 (14): 2358–65. doi:10.1002/jsfa.4092. PMID 20632382.

- ↑ Author: Natty Netsuwan. "Green Papaya Salad Recipe". ThaiTable.com. Retrieved 2013-06-15.

- ↑ Titanji, V.P.; Zofou, D.; Ngemenya, M.N. (2008). "The Antimalarial Potential of Medicinal Plants Used for the Treatment of Malaria in Cameroonian Folk Medicine". African Journal of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicines 5 (3): 302–321. PMC 2816552. PMID 20161952.

- ↑ "Re:Papaya leaves for speedy rise of platelet count in Dengue". BMJ. Retrieved 2013-06-15.

- ↑ Harrison Ford: The Films. McFarland & Company. 2005. pp. 113–. ISBN 978-0-7864-2016-2.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - ↑ Lohiya, N. K.; B. Manivannan; P. K. Mishra; N. Pathak; S. Sriram; S. S. Bhande; S. Panneerdoss (March 2002). "Chloroform extract of Carica papaya seeds induces long-term reversible azoospermia in langur monkey". Asian Journal of Andrology 4 (1): 17–26. PMID 11907624. Retrieved 2006-11-18.

- ↑ Oderinde, O; Noronha, C; Oremosu, A; Kusemiju, T; Okanlawon, OA (2002). "Abortifacient properties of Carica papaya (Linn) seeds in female Sprague-Dawley rats". Niger Postgrad Medical Journal 9 (2): 95–8. PMID 12163882.

- ↑ Rahmat, Asmah et al. "Antiproliferative activity of pure lycopene compared to both extracted lycopene and juices from watermelon (Citrullus vulgaris) and papaya (Carica papaya) on human breast and liver cancer cell lines".

- ↑ "Papaya extract thwarts growth of cancer cells in lab tests". Retrieved 3 March 2010.

- ↑ "The in vitro assessment of antibacterial effect of papaya seed extract against bacterial pathogens isolated from urine, wound and stool.". Retrieved 14 October 2009.

- ↑ "Search the USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference". Nal.usda.gov. Retrieved 2010-08-18.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carica papaya. |

| Look up Papaya in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikibooks Cookbook has a recipe/module on |

- Fruits of Warm Climates: Papaya and Related Species

- California Rare Fruit Growers: Papaya Fruit Facts

- Purdue: Carica papaya

- Papaya Nutrition Data

- Papaya production statistics worldwide

- Treating Livestock with Medicinal Plants: "Beneficial or Toxic? Carica papaya"