Pan-nationalism

| Part of a series on |

| Nationalism |

|---|

|

|

Core values |

|

Organizations |

| Politics portal |

Pan-nationalism is a form of nationalism distinguished by being associated with a claimed national territory which does not correspond to existing political boundaries. It often defines the nation as a ‘‘cluster’’ of supposedly related ethnic or cultural groups. It shares the general nationalist premises that the nation is a fundamental unit of human social life, and that it is the only legitimate basis for the state.

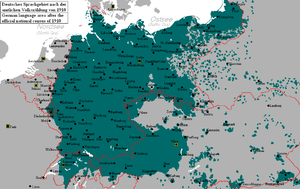

Some pan-nationalisms, such as pan-Germanism, were mono-ethnic, like standard nationalism. The prefix ‘pan-’ was used because the ethnic Germans were dispersed over much of Central Europe. In other cases pan-nationalists speak of the ‘peoples’ (for instance ‘the Turkic peoples’), whereas classic nation-states have one ethnicity, culture and language.

History and outcomes

Pan-nationalism implies that the ‘national group’ is dispersed over several existing states. It is not identical to irredentism - nationalist claims on adjoining territories on the grounds that they form part of the national homeland. Scale is a factor here, however. Greater Albania, even in the largest version, would still be a small country. An irredentist Greater Germany, even if it is limited to contiguous German-speaking regions, would have about 100 million inhabitants. Pan-nationalism is not the same as diaspora nationalism, such as Zionism, which implies the concentration of a dispersed group on an ancestral homeland. Colonies (other than settler colonies) fall outside most definitions of a nation, since both coloniser and colonised recognise that they share no ethnicity, culture, and language.

Nationalist movements in large nations, such as the German and Russian nations, are therefore difficult to distinguish from pan-nationalist movements, and often there are explicitly pan-nationalist elements. Aside from these cases, however, most pan-nationalist movements failed. Specifically pan-national states are rare. Yugoslavia attempted to unify a category of South Slavs, the prefix "jugo" means "south". After 1945, it did recognise separate internal nations, with their own governments.

Other large states are difficult to classify as pan-national. Around 1942 Nazi Germany controlled a vast collection of annexed territories, German-administered civilian entities, puppet states, collaborationist states, and front-line areas run by the military. The conquests were partly inspired by the idea of Lebensraum, but that is not in itself a pan-nationalist concept. The Soviet Union had a Soviet identity, but no ‘Soviet’ ethnicity, culture, or language. It was influenced by pan-Russian ideas, but also by other geopolitical ideals which implied a large territory. China has a long tradition of cultural and administrative unity. (The fact that both China and India annexed territories, does not necessarily make the state pan-national in character).

The general failure of the pan-nationalist movements is illustrated by several examples, which had a clear idea of their ideal state, but never got anywhere near achieving it. Modern Turkey is the former core area of the Ottoman Empire. The present state is closely modelled on the classic European nation state, and was a deliberate break with that empire. Beside the very strong Turkish nationalism there are three pan-nationalisms. In ascending order of scale: pan-Turkism, a sometimes distinct pan-Turkic ideology referring to the Turkic peoples, and pan-Turanism, which covers most of central Asia and even Finland and Hungary. As in Turkey, pan-nationalist movements often operate on the margin of a more limited ‘standard-nationalist’ movement, in the existing core area of the claimed mega-state.

Pan-Slavism is another notable example of an influential ideal that never resulted in the corresponding mega-state - if Russian territory was included, it would extend from the Baltic to the Pacific (west to east) and right down to central Asia and the Caucasus/Black Sea/Mediterranean in the south.

Pan-Americanism as an ideal was influential around the time of the independence movements in Latin America. However, the new nation-states soon diverged in policy and interests, and no federation emerged. The term acquired another meaning, namely U.S.-led co-operation among the separate nation-states, with a connotation of U.S. hegemony. That is why there is a pan-Latin-Americanism which proposes inter-Americanism with the United States. An important exponent of this philosophy is Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre, from Peru, while Bolivarianism represents a current variation on the theme.

Pan-Arabism favors the unification of the countries of the Arab world, from the Atlantic Ocean to the Arabian Sea.

Recent developments

Thomas Hegghammer of the Norwegian Defence Research Establishment has outlined the emergence of "macro-nationalism" in the late Cold War era, which kept a low profile until the September 11 attacks. Hegghammer traces the origins of modern macro-nationalism to both the Western counter-jihad movement and Islamic terrorist organisations such as al-Qaeda. In the aftermath of the 2011 Norway attacks, he described the ideologies of perpetrator Anders Behring Breivik as "not fitting the established categories of right-wing ideology, like white supremacism, ultranationalism or Christian fundamentalism", but more akin to a "doctrine of civilisational war that represents the closest thing yet to a Christian version of Al-Qaeda".[1]

Other definitions

Over the past few years, pan-nationalism has also been used by organizations such as the Pan-Nationalist Movement, to describe a political ideal which seeks to give every nation, described as an amalgamation of ethnicity and culture their own state. This is more popularly and historically known as self-determination.

See also

- Pan-Africanism

- Pan-Asianism

- Pan-Southeast Asianism

- Pan-Celticism

- Pan-European nationalism

- Pan-Iranism

- Pan-Islamism

- Pan-Scandinavianism

- Pan-Slavism

- Pan-Somalism

- Pan-Turkism

- Expansionist nationalism

- Irredentism

- Atlanticism

- Caliphate

- Colonialism

- Diaspora

- Empire

- Imperialism

- Ummah

- Megali Idea

- Civic nationalism and ethnic diversity - which when combined (as in Canada or United States ) also results in a multi-ethnic version of nationalism

References

- ↑ Thomas Hegghammer (30 July 2011), The Rise of the Macro-Nationalists

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||