Palmyra

| Palmyra | |

|---|---|

|

ܬܕܡܘܪܬܐ (Aramaic) تدمر (Arabic) | |

|

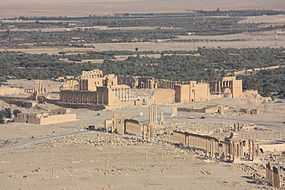

Overview of Palmyra's historic site. | |

Shown within Syria | |

| Alternate name | Tadmur |

| Location | Tadmur, Homs Governorate, Syria |

| Region | Syrian Desert |

| Coordinates | 34°33′36″N 38°16′2″E / 34.56000°N 38.26722°ECoordinates: 34°33′36″N 38°16′2″E / 34.56000°N 38.26722°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Area | 50 ha (120 acres) |

| History | |

| Founded | 2nd millennium BC |

| Abandoned | 1932 AD |

| Periods | Bronze Age to Modern Age |

| Cultures | Aramaic, Arabic, Greco-Roman |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Ownership | Public |

| Public access | Yes |

| Official name | Site of Palmyra |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iv |

| Designated | 1980 (4th session) |

| Reference no. | 23 |

| State Party |

|

| Region | Arab States |

Palmyra /ˌpælˈmaɪərə/, (Aramaic: ܬܕܡܘܪܬܐ; Arabic: تدمر; Hebrew: תַּדְמוֹר; Ancient Greek: Παλμύρα), was an ancient Semitic city, located in Homs Governorate, Syria. Dating back to the Neolithic, Palmyra was first attested in the early second millennium BC, as a caravan stop for travelers crossing the Syrian Desert. The city is mentioned in the Hebrew Bible and in the annals of the Assyrian kings, then it was incorporated into the Seleucid Empire, followed by the Roman Empire which brought great prosperity.

Palmyra's wealth allowed the construction of many monumental projects. By the third century, Palmyra was turned into a prosperous metropolis, with a strong army capable of defeating the Sassanid empire in 260. Following the victory, Palmyra's chief Odaenathus was proclaimed king but was assassinated in 267. He was succeeded by his minor son, under the regency of queen Zenobia, who started invading the Roman eastern provinces in 269. The rebellion was masked by a nominal subordination to Rome. However, the situation escalated and the Palmyrene rulers adopted the imperial titles in 271. Roman emperor Aurelian defeated Palmyra in 272, and destroyed it in 273 after a failed second rebellion. Palmyra became a minor city under the rule of the Byzantines, Rashiduns, Ummayads, Abbassids, Mamluks, and their vassals. After being destroyed by the Timurids in 1400, Palmyra remained a small village under the rule of the Ottomans until 1918, then the Syrian kingdom, followed by the French mandate. In 1929 the French started evacuating the villagers into the newly built village of Tadmur. The evacuation was completed in 1932 and the site became abandoned and available for excavations.

The Palmyrenes were mainly a mix of Amorites, Arameans and Arabs,[1] in addition to a Jewish minority. The society was tribal and the inhabitants spoke their own dialect of Aramaic, in addition to Greek. Both of the languages were replaced by Arabic following the Arab conquest in 634. Palmyra's local culture was influenced by the Greco-Roman and Persian cultures, which produced a distinctive art and architecture. The city's inhabitants worshiped local deities, in addition to Mesopotamian and Arab gods. They later converted to Christianity in the fourth century, followed by Islam in the second half of the first millennium.

The Palmyrene political organization was based on the Greek city-state model, it was governed by a senate responsible for the public works and the military. After gaining the status of a Colonia in the third century, Palmyra's incorporated Roman institutions to its system before adopting a monarchical system in 260. Palmyra gained its wealth from caravan trade. The Palmyrenes were renowned merchants who established colonies along the Silk Road, and conducted their operations all around the Roman empire.

Location and etymology

Palmyra is located 215 km (134 mi) to the northeast of the Syrian capital Damascus,[2] in an oasis,[3] surrounded by palms of which twenty varieties were reported.[4] A small Wadi named al-Qubur, crosses the area,[5] it flows from the hills in the west and passes the city, before disappearing in the eastern gardens of the oasis.[6] To the south of the Wadi, a spring named Efqa is located.[7] Pliny the Elder described the town in the 70s AD,[note 1] as famous for its location, the richness of its soil,[9] and the water springs that surrounded it, making the agricultural and herding activities possible.[9]

Tadmor is the Semitic and earliest attested native name of the city, it appeared in the first half of the second millennium BC.[10] The etymology of Tadmor is vague, Albert Schultens considered it to be derived from the Semitic word for dates (Tamar),[note 2][12] in reference to the Palm trees that surround the city.[note 3][4] The name Palmyra appeared during the early first century AD,[10] in the works of Pliny the Elder,[13] and was used throughout the Greco-Roman world.[12] The general view holds that Palmyra is derived from Tadmor either as an alteration, which was supported by Schultens,[note 4][12] or as a translation using the Greek word for palm (Palame),[note 5][4] which is supported by Jean Starcky.[10]

Michael Patrick O'Connor argued for a Hurrian origin of both Palmyra and Tadmor,[10] citing the incapability of explaining the alterations to the theorized roots of both names, which are represented in the adding of a -d- to Tamar and a -ra- to palame.[4] According to this theory, Tadmor is derived from the Hurrian word Tad, meaning to love, + a mid vowel rising (mVr) formant Mar. Palmyra is derived from the word Pal, meaning to know, + the same mVr formant Mar.[15]

History

The site of Palmyra provided evidence for a neolithic settlement near Efqa,[17] with stone tools discovered and dated to 7500 BC.[18] The use of archaeoacoustics in the Tell beneath the Temple of Bel revealed traces of a cultic activity dated to 2300 BC.[19][20][21]

Early period

Palmyra entered the historic records in c. 2000 BC, when a certain Puzur-Ishtar the Tadmorean made a contract at an Assyrian trading colony in Kultepe.[18][22] Palmyra was next mentioned in the Tablets of Mari as a station for trade caravans, and the halting place for many nomadic tribes such as the Suteans.[23] King Shamshi-Adad I of Assyria passed the area on his way to the Mediterranean, at the beginning of the 18th century BC.[24] By then, Palmyra was the kingdom of Qatna's most eastern point.[25] The town was mentioned in a tablet discovered at Emar dated to the 13th century BC, and records the names of two Tadmorean witnesses.[23] At the beginning of the 11th century BC, king Tiglath-Pileser I of Assyria recorded in his annals the defeat he inflicted upon the Arameans of Tadmar.[23]

The Hebrew Bible (Second Book of Chronicles 8:4) records Tadmor as a desert city built or fortified by King Solomon of Israel,[26] it is likewise mentioned in Talmud (Yebamot 17a-b).[27] Flavius Josephus' mention the Greek name Palmyra and also attribute the founding of Tadmor to Solomon in his Antiquities of the Jews (Book VIII).[28] Later Islamic traditions attributes the founding of the city to the Jinn of Solomon.[29] The association of Palmyra with Solomon could be a confusion between Palmyra (Tadmor), and a city built by Solomon in the land of Judea, mentioned in the Books of Kings (9:18) as Tamar.[30] The description of Tadmor and its buildings in the Bible, does not fit the known archaeological findings of Palmyra, which was a mere settlement during the days of Solomon in the 10th century BC.[30]

Hellenistic and Roman periods

The Hellenistic period under the Seleucids saw Palmyra turning into a prosperous settlement,[30] that owed allegiance to the Seleucid monarch.[31] In 217 BC, a Palmyrene force led by a Sheikh named Zabdibel,[note 6] joined the army of king Antiochus III in the Battle of Raphia.[33] Toward the middle of the Hellenistic era, Palmyra, formerly restricted in the south of al-Qubur's wadi, started to expand beyond the northern bank.[34] By the late second century BC, the tower tombs in the Palmyrene Valley of Tombs began to be constructed,[33] in addition to the city temples, most importantly the temples of Baalshamin, Al-lāt and the Hellenistic temple.[30][35]

In 64 BC, the Roman Republic annexed the Seleucid kingdom, and the Roman general Pompey established the province of Syria, but Palmyra was left independent,[33] trading with both Rome and Parthia but belonging to neither.[36] The earliest known Palmyrene inscription is dated to c. 44 BC,[37] and by then, Palmyra was still a minor Sheikhdom, offering water to caravans that occasionally took the desert route, along which Palmyra was situated.[38] However, according to Appian, Palmyra was wealthy enough for Mark Antony to send a force aimed at conquering it in 41 BC.[36] The Palmyrenes evacuated and headed into Parthia's lands beyond the Euphrates eastern bank,[36] which they prepared to be defended.[37]

Palmyra became part of the Roman Empire when it paid tribute in the early years of emperor Tiberius' reign c. 14 AD.[33] The Roman imperial period brought a great prosperity to Palmyra, which enjoyed a privileged status under the empire and retained much of its internal autonomy.[33] The Romans defined the boundaries of Palmyra's region, a boundary marker established by Roman governor Silanus was found 75 kilometers to the northwest of Palmyra at Khirbet el-Bilaas.[39] Another marker that defined Palmyra's southwestern borders was found at Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi,[40] while the borders in the east extended to the Euphrates valley.[40]

The earliest Palmyrene text that attests the Roman existence in the city is dated to 18 AD, when the Roman general Germanicus sought to establish a friendly relation with Parthia, and sent a Palmyrene named Alexandros to Mesene, a Parthian vassal kingdom.[note 7][42] This was followed in 19 AD, by the arrival of Legio X Fretensis.[note 8][44] The Roman authority was minimal during the first century, they had tax collectors in the city,[45] and built a road that connected Palmyra with Sura in 75 AD.[note 9][46] The Romans also made use of Palmyrene soldiers,[47] however, no local magistrates or prefects are recorded in the city as it was the case for typical Roman cities.[46] Palmyra witnessed an intense construction movement during the first century, which included the city's first walled fortifications,[44] and the Temple of Bel, which was finished and dedicated in 32 AD.[48] The first century saw Palmyra's transformation from a minor desert station for caravans into a leading trading center,[note 10][38] with the Palmyrene merchants establishing colonies in many of the surrounding important trade centers.[42]

Prosperity

.jpg)

The Palmyrene trade reached its apex during the second century.[50] Two factors helped Palmyra achieving its status, the first was the trade route that the Palmyrenes built,[9] and protected by maintaining garrisons along the important locations, including a garrison in Dura-Europos which was stationed by 117.[51] The second factor was the Roman annexation of the Nabataean capital Petra in 106,[33] which led to the collapse of Nabataean control over the southern trade routes from Arabia, and their shifting to Palmyra.[note 11][33]

.jpg)

In 129, Palmyra was visited by emperor Hadrian, who named it Hadriane Palmyra and granted it the status of a free city,[53][54] Hadrian promoted Hellenism throughout the empire,[55] and Palmyra's urban expansion was modeled on the Greek fashion,[55] leading to many new projects, including the theatre, the colonnade and the temple of Nabu.[55] The Roman authority in the city was reinforced in 167, when the garrison Ala I Thracum Herculiana was moved to Palmyra.[56]

During the third century, Palmyra started a steady transition toward a monarchical system instead of a traditional Greek city-state model,[57] and the urban development diminished,[58] as the city had reached the apogee of its building projects.[58] The ascendance of the Severan dynasty to the imperial throne in Rome played a major part in Palmyra's transition.[58] Firstly, the new dynasty favored the city,[59] and stationed the Cohors I Flavia Chalcidenorum as a garrison by 206.[60] Palmyrene militias were given a prominent role in the protection of the Roman frontiers in eastern Syria,[61] and emperor Caracalla elevated Palmyra into a Colonia between 213 and 216, which brought new constitutional institutions that replaced many of the Greek ones.[57] Secondly, the Severan led Roman-Parthian war which lasted from 194 to 217 influenced the regional security and affected the trade of the city.[59][62] Bandits started to attack the caravans by 199, leading Palmyra to strengthen its military abilities,[59] and the Palmyrene forces started to get more engaged in the protection of the Roman east instead of protecting the trade,[61] leading to an increase in the importance of the city,[61] which was visited by emperor Alexander Severus before his death in 235.[59]

Palmyrene kingdom and Persian wars

The rise of the Sassanid dynasty in Persia damaged the Palmyrene trade considerably.[63] The Sassanids disbanded the Palmyrene colonies in their lands,[63] and started a full scale war against the Roman empire.[64] Around 251, Odaenathus appeared in a document with the titles exarchos and senator of Palmyra, sharing these titles with his son Hairan.[note 12][57][66] Odaenathus approached Shapur I of Persia to guarantee the Palmyrene interests in Persia but was rebuffed,[67] and soon had to fight Shapur after the disastrous Roman defeat at the Battle of Edessa in 260.[64] The aforementioned battle ended with emperor Valerian's capture and soon —Macrianus Major, his sons Quietus and Macrianus, and Balista the prefect— rebelled against Valerian's son Gallienus and usurped the imperial power in Syria.[68]

Odaenathus remained loyal to Gallienus and formed an army of Palmyrenes, peasants and what remained of the Roman soldiers in the region to resist Shapur.[64] The Palmyrene leader won a decisive victory over Shapur in a battle near the banks of the Euphrates in 260.[68] This was followed by reclaiming the Roman Mesopotamia,[68] and besieging the Persian capital Ctesiphon.[69] As a reward, the victorious Palmyrene received the title Imperator Totius Orientis (Governor of the East) from Gallienus,[70] ruling Syria as the imperial representative.[71] Personally, Odaenathus declared himself king or King of Kings,[note 13][73] and in 261, he marched against the remaining usurpers in Syria, defeating and killing Quietus and Balista.[68] This was followed by a new war against Persia in 262.[74][75]

After defeating a Persian army in 263 or 264, Odaenathus crowned his son Hairan as co-king near Antioch,[76] then marched in 264 and besieged Ctesiphon for the second time.[77] Although not successful in taking the Persians' capital, Odaenathus drove them out of all the Roman lands they conquered since the beginning of Shapur's wars in 252.[77] The Persians unsuccessfully campaigned against Palmyra but were repelled,[78] and then defeated by Odaenathus in 266 near Ctesiphon.[68] The Palmyrene monarch then headed north to repel the Goth's attacks on Asia Minor in 267,[68] but was assassinated along with Hairan on their returning way.[68] According to the Augustan History and John Zonaras, Odaenathus was killed by his cousin whose name in the Augustan History is Maeonius.[79] The Augustan History also claims that Maeonius was proclaimed emperor for a very brief period, before being trialed and executed by Odaenathus' widow Zenobia.[79][80][81] However, no inscriptions or other evidence exist for Maeonius reign, and he was probably killed immediately after assassinating Odaenathus.[82][83]

Palmyrene empire

Odaenathus was succeeded by his ten-year-old son Vaballathus under the regency of Zenobia, the mother of the new king.[84] Zenobia was the real ruler of Palmyra, and Vaballathus remained in the shadow while his mother consolidated her power.[84] The queen was careful not to provoke Rome and claimed for herself and her son the titles that her husband had, while working on guaranteeing the safety of the borders with Persia, and pacifying the dangerous Tanukhid tribes in Hauran.[84]

Zenobia started her military career in the spring of 270, during the reign of emperor Claudius II.[85] Under the cover of attacking the Tanukhids, Zenobia annexed the Roman Arabia.[85] This was followed in October of 270 by an invasion of Egypt,[86][87] that ended with a Palmyrene victory and Zenobia's proclamation as queen of Egypt.[88] Afterward, Palmyra invaded Asia Minor in 271 and reached Ankara, marking the greatest extent of the Palmyrene expansion.[89]

Those conquests were conducted under the mask of subordination to Rome,[90] Zenobia issued the coinage in the name of Claudius' successor Aurelian as emperor, with Vaballathus depicted as king,[note 14] while Aurelian allowed the Palmyrene coinage and conferred the Palmyrene royal titles, as he was occupied in repelling numerous insurgencies in Europe.[91] Toward the end of 271, Vaballathus took the title of Augustus (emperor) along with his mother.[note 15][90]

In 272, Aurelian crossed the Bosphorus and advanced quickly through Anatolia.[95] According to one account, Roman general Marcus Aurelius Probus regained Egypt from Palmyra,[note 16][96] while Aurelian continued his march entering Issus and heading to Antioch, where he defeated Zenobia in the Battle of Immae.[97] Zenobia was defeated again at the Battle of Emesa and took refuge in the city, but evacuated quickly back to her capital.[98] The Romans besieged Palmyra and tried to negotiate with Zenobia, on the condition that she surrender herself in person to the emperor, to which she answered with refusal.[89] The empress escaped the city and headed east to ask the Persians for help, but was captured and soon after, the city capitulated.[99][100]

Later Roman and Byzantine periods

Aurelian spared the city and stationed a garrison of 600 archers led by a certain Sandarion, as a peacekeeping force.[101] However, in 273, Palmyra rebelled under the leadership of a citizen named Septimius Apsaios,[94] and declared a relative of Zenobia named Antiochus as Augustus.[102] Aurelian marched against Palmyra and this time razed it to the ground,[103] the most valuable monuments were taken by the emperor to decorate his Temple of Sol,[99] while Palmyrene buildings were smashed, people were clubbed and cudgeled and the temple of Bel pillaged.[99]

Palmyra was reduced to a village with no territory to rule, Aurelian repaired the temple of Bel, and the Legio I Illyricorum was stationed in the city.[104] Shortly before 303, the Camp of Diocletian, a Castra in the western side of the city was built.[104] The camp enclosed an area of four hectares as a military base for the Legio I Illyricorum,[104] which guarded the trade routes around the city.[105]

Palmyra became a Christian city in the decades following the destruction by Aurelian.[106] In late 527, Justinian I ordered the fortification of Palmyra, and the restoring of its churches and public buildings.[107] This was a step to protect the empire against the raids of the Lakhmid king Al-Mundhir III ibn al-Nu'man.[107]

Arab caliphate

Palmyra was captured by the Rashidun Caliphate under Khalid ibn al-Walid in 634, and by then, it was limited to the Diocletian camp.[108] Palmyra witnessed some prosperity during the Ummayad era,[109] but had its walls demolished by caliph Marwan II in 745 due to a local revolt.[108][110] In 750, a revolt against the newly established Abbasid dynasty, led by Majza'a ibn al-Kawthar and an Ummayad pretender named Abu-Muhammad al-Sufyani, swept across Syria,[111] and the tribes of Palmyra supported the rebels.[112] After being defeated, Abu-Muhammad took refuge in the Palmyra, which withstand the Abbasid attack long enough, giving the rebel a chance to escape.[112]

Decentralized caliphate

Abbasid power dwindled in the 10th century, the empire disintegrated and was divided between different vassals.[113] Most of the new rulers acknowledged the caliph as their nominal sovereign, a situation that continued until the Mongol destruction of the Abbasid caliphate in 1258.[114]

In 955, Sayf al-Dawla, the Hamdanid prince of Aleppo, defeated the nomads near the city,[115] and built a Kasbah (fortress) in response to the campaigns of the Byzantine emperors Nikephoros II Phokas and John I Tzimiskes.[116] Following the Hamdanids demise in the beginning of the 11th century, Palmyra was controlled by their successors the Mirdasids.[117] Earthquakes devastated the city in 1068 and 1089.[108][118] The Mirdasids were followed in the second half of the 11th century, by prince Khalaf of the Mala'ib tribe centered in Homs.[119] However, in the 1070's, the whole of Syria came under the authority of the Seljuks,[120] whose sultan Malik-Shah I expelled the Mala'ib and imprisoned Khalaf in 1090.[121] Khalaf's lands were rewarded to Malik-Shah's brother Tutush I,[121] who gained his independence following his brother's death in 1092, establishing a cadet branch of the Seljuq dynasty in Syria.[122]

.jpg)

In the early 12th century, Palmyra came under the authority of Toghtekin, the Burid Atabeg of Damascus, who appointed his nephew as a governor.[123] Toghtekin's nephew was killed, causing the Atabeg to march and retake the city in 1126.[123] Then Palmyra was given to Toghtekin's grandson, Shihab-ud-din Mahmud,[123] who was replaced by a governor named Yusuf ibn Firuz,[124] after the former went back to Damascus following his father Taj al-Muluk Buri's succession.[124] The Burids turned the temple of Bel into a citadel in 1132 and fortified the city,[125][126] then transferred it to the Bin Qaraja family in 1135 in exchange for Homs.[126]

In the middle of the 12th century, the city was incorporated to the realm of the Zengid king Nur ad-Din Mahmud.[127] It became part of Homs district,[128] which was given as a fiefdom to the Ayyubid general Shirkuh in 1167,[129] but confiscated following his death in 1169.[130] Homs district was annexed by the Ayyubid sultanate in 1174,[131] and in 1175, Sultan Saladin gave Homs including Palmyra as a fiefdom to his cousin Nasir al-Din Muhammad.[132] Following Saladin death, the Ayyubid realm was divided and the city was conferred upon Nasir al-Din Muhammad's son Al-Mujahid Shirkuh II,[133] who built the castle of Palmyra commonly known as Fakhr-al-Din al-Maani Castle in c. 1230.[134]

Mamluk period

Palmyra was used as a refuge by Sherkoh II's grandson Al-Ashraf Musa, who allied himself with the Mongol king Hulagu Khan, but fled after the Mongols defeat in Ain Jalut 1260.[135] Al-Ashraf Musa asked the Mamluk sultan Qutuz for pardon and was accepted by the latter as a vassal, bringing Palmyra to the realm of the Mamluks.[135]

Al-Fadl principality

Al-Fadl clan, a branch of the Tayy tribe, declared its loyalty to the Mamluks,[136][137] and in 1284, Muhanna bin Issa, the prince of the tribe, was appointed by sultan Qalawun as the lord of Palmyra.[136] However, he was imprisoned by sultan Al-Ashraf Khalil in 1293, then restored in 1295 by sultan Al-Adil Kitbugha.[136] Muhanna declared his loyalty to Öljaitü of the Ilkhanate in 1312 and was dismissed by sultan Al-Nasir Muhammad, who replaced him by his brother Fadl.[136] Muhanna asked Al-Nasir forgiveness and was restored in 1317, only to be expelled with his whole tribe and be replaced by another tribal chief named Muhammad ibn Abi Bakr, for his continuing relations with the Ilkhanate.[136][138]

Muhanna was forgiven and restored by Al-Nasir in 1330, he remained loyal to the sultan, dying in 1333, and was succeeded by his son.[139] Historian Ibn Fadlallah al-Omari described the city as boasting "vast gardens, flourishing trades and bizarre monuments".[140] The Fadl family protected the trade routes and the villages from Bedouin raids,[141] but conducted raids against other cities themselves, and fought between each others, causing the Mamluks to interfere militarily, dismissing, imprisoning or expelling the leaders on several occasions.[139] In 1400, Palmyra was attacked by Timur,[142] who took 200,000 sheep,[143] and destroyed the city.[144] The Fadl prince, Nu'air, escaped the fight with Timur, then fought against Jakam, the sultan of Aleppo.[145] Nu'air was captured, taken to Aleppo and executed in 1406, which according to Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani, broke the Fadl family power.[145]

Ottoman and later periods

Syria became part of the Ottoman empire in 1516,[146] and Palmyra was incorporated into the Eyalet of Damascus, and made the center of a Salyane Sanjak.[note 17][147] During the Ottoman period, Palmyra was a small village restricted to the court of Bel's temple.[148] After 1568, the Ottomans appointed the Lebanese prince Ali bin Musa Harfush as governor of Palmyra's Sanjak,[149] then dismissed him in 1584 for treason.[150]

In 1630, the city came under the authority of another Lebanese prince, Fakhr-al-Din II,[151] who renovated Sherkoh II's castle,[152] which became known as Fakhr-al-Din al-Maani Castle.[134] The prince fell from grace with the Ottomans in 1633 and lost control over Palmyra,[151] which remained a Sanjak until incorporated to Deir ez-Zor Sanjak in 1857.[153] Palmyra became the center of an Ottoman garrison to control the Bedouins in 1867.[154]

Palmyra regained some of its importance in the beginning of the 20th century, as a station for caravans whose revival was helped by the arrival of the motorized vehicles.[148] In 1918, as the World War I was coming to an end, the Royal Air Force established an airfield that served two airplanes,[note 18][155][156] and in November 1918, the Ottomans retreated from Zor Sanjak without a fight.[note 19][157] The Syrian Emirate's army entered Deir ez-Zor in 4 December 1918, and the Sanjak became part of Syria.[158] Following the war In 1919, as the British and French argued over the borders of the planned Mandates,[155] Henry Wilson, the British Permanent Military Representative at the Supreme War Council, suggested adding Palmyra to the British mandate.[155] However, British general Allenby persuaded his government to abandon this plan,[155] and Syria along with Palmyra became part of the French Mandate, following the Syrian defeat at the Battle of Maysalun in 24 July 1920.[159]

As Palmyra gained importance in the French efforts to pacify the Syrian Desert, a base was built in the village near the temple of Bel in 1921.[160] In 1929, Henri Arnold Seyrig, the general director of antiquities in Syria, started excavating the ruins and convinced the villagers to relocate into a newly French built village, adjacent to the ancient site.[161] The relocation was completed in 1932,[162] making the ancient Palmyra ready for excavations,[161] while the villagers settled in the new village that retained the name Tadmur.[163]

People, language and society

At its height during the reign of Zenobia, Palmyra had more than 200,000 resident.[164] The earliest known inhabitants of Palmyra were the Amorites from the early second millennium BC,[165] and by the end of that millennium, the Arameans were mentioned as the inhabitants of the area.[166][167] Arabs arrived in the city in the late first millennium BC; Zabdibel's soldiers who aided the Seleucids in the battle of Raphia (217 BC), were described as Arabs.[33] The newcomers were assimilated by the earlier inhabitants, spoke their language,[37] and formed an important part of the aristocracy.[168][169] The city also included a Jewish minority, inscriptions written in Palmyrene from the necropolis of Beit She'arim in Lower Galilee, confirms the burial of some Palmyrene Jews in it.[170]

By the time of the Rashidun conquest in 634, the city was inhabited by Christian Arabs.[171][172] In the twelfth century, Benjamin of Tudela recorded the existence of 2000 Jews in the city,[173] which after the invasion by Timur, remained a small Arab village,[174] of thirty or forty families,[175] until the relocation of the inhabitants in 1932.[162]

The pre 272 AD Palmyrenes spoke their own dialect of the Aramaic language and wrote using the Palmyrene alphabet.[176][177] Greek was used by the wealthier parts of the society for commercial and diplomatic reasons, while the use of Latin was minimal.[1] Greek became the dominant language during the era of the Byzantine empire, then, after the Arab conquest, it was replaced by Arabic,[21] from which a Palmyrene dialect evolved.[178]

The society of pre 272 AD was the result of mixture between the different peoples that inhabited the city,[23][179] which is manifested in the Aramaic,[note 20] Arabic,[note 21] and Amorite names of the clans.[note 22][180][181] Palmyra was a tribal community,[182] however, the tribal character is not to be understood in a nomadic sense, but as a social grouping for people who have a common patrilineal descent with no political role, hence a tribe in Palmyra was mostly an extended family instead of political organization.[183] In total, fourteen clans are attested,[183] five of them were identified as tribes (Phyle (φυλή)),[note 23] comprising several sub-clans.[183] By the time of Nero, Palmyra was split into four tribes residing in four quarters, each quarter was named after the tribe that resided in it, those were the Komare, the Mattabol and the Ma'zin,[184] while the fourth tribe's name is unknown with certainty but most probably it was the Mita.[184][185] As the time passed, the four tribes became highly superficial and civic,[note 24][184] while the rest of the clans might have gathered under the name of the four tribes, for by the second century, any notion of a clan lost its importance and disappeared in the following third century.[184] Later periods saw Palmyra's decline and transformation into a small village numbering 6000 at the beginning of the 20th century, and although surround by Bedouins, the villagers managed to preserve their own dialect,[178] and maintain an urban life of a small settlement.[108]

Culture

Palmyra had a distinctive culture,[187] which was influenced by the Greco-Roman culture.[188] However, beneath the foreign influence, a local Semitic tradition defined the culture of the city,[note 25][190] and according to Fergus Millar, Palmyra's culture is the result of fusion between the local and Greco-Roman traditions.[191] In addition to the western influence, the culture of Persia manifested its influence in the Palmyrene upper classes fondness of hunting,[192] and in the Palmyrene art, military tactics, dress and court ceremonials.[192] Palmyra lacked the intellectual movement that characterized other eastern cities such as Edessa or Antioch, as it contained no large libraries or publishing facilities.[193] Zenobia opened her court to academics, however, the only notable scholar attested at the Palmyrene court was Cassius Longinus.[193]

The city included a large Agora.[note 26] However, unlike the Greek Agoras which served as a place for public gatherings and a square shared by the civic public buildings, Palmyra's Agora belonged to the eastern tradition, and was closer to a Caravanserai and a marketplace than to a hub of public life.[195][196] The Palmyrenes buried their dead in elaborate family mausoleums,[197] that had its interior walls constructed to form rows of burial compartments, in which the deceased, laid at full length, were placed.[198][199] Reliefs that represented the person interred formed part of the walls' decoration and functioned as a headstone.[199] Some of the tombs contained mummies in full dress and jewelry,[200] and the embalming methods used were similar to the methods used in Egypt.[201]

Art and architecture

The Palmyrene art was related to the Hellenistic art, but had its own distinctive style, local to the wider middle Euphrates region.[202] Palmyrene art is best represented by the iconography of the deities, and the human bust reliefs that sealed the openings of the burial compartments.[202] It was characteristic for focusing on the clothing, the attention for details such as jewelry,[203] and the frontal representation of the person it depicted.[202] Those characters could be seen as a forerunner for the later Byzantine art.[202]

Similar to its art, Palmyra's architecture was influenced by the Greco-Roman style,[204] but preserved local elements, which are best represented in the Temple of Bel.[205] Although inclosed by a massive wall flanked with traditional Roman columns,[205][206] Bel's sanctuary was mostly Semitic in its general plan.[205] Similar to the Second Temple, Bel's sanctuary consisted of a large courtyard, with the deity's main shrine located non centrally against the entrance of the sanctuary,[205] in a plan that preserve elements found in the temples of Ebla and Ugarit.[207]

Government

From the beginning of its history until the first century AD, Palmyra was a petty sheikhdom,[208] but by the first century BC, a concept of Palmyrene identity started to develop.[209] In the first half of the first century, the city adopted the institutions of a Greek city (polis).[210] The concept of citizenship (demos) appears in an inscription dated to 10 AD, describing the Palmyrenes as a community.[211] In 74 AD, another inscription mentions the boule (senate) of the city.[210] The military units of Palmyra were headed by the strategoi (generals),[212] while the boule managed the civic responsibilities,[213] and appointed two archons (lords) annually.[214][215] The boule consisted out of approximately six hundred members,[note 27] hailing from the local elite, such as the elders or heads of the wealthy families or clans,[213] who represented the four quarters of the city.[185] The Palmyrene boule was headed by a president,[215] and supervised the public works (e.g. the construction of public buildings), approved the expenditures and managed the collection of taxes.[213]

With the elevation of Palmyra into a colonia (c. 213-216), the city incorporated Roman institutions to its system, but kept most of its Greek institutions.[216] The boule remained and the strategos title came to designate one of two annually elected magistrates,[216] who constituted the duumviri which managed the new colonial constitution,[216] and replaced the archons.[214] The political scene in Palmyra changed with the rise of Odaenathus, who was attested as senator and exarch (chief) of Palmyra along with his son Hairan in 251.[66] The exact meaning of Odaenathus' title, whether it indicated a military or a priestly position, is unknown.[66] By 257, Odaenathus was referred to as consularis, which might indicate that he became the legatus of the Syria Phoenice province.[66] Starting in 258, Odaenathus extended his political influence taking advantage of the instability in the region, caused by the Sassanid aggressions,[66] which culminated with the Battle of Edessa,[64] Odaenathus' mobilization of troops, his war with the Persians, and his subsequent royal elevation that turned Palmyra into a kingdom.[64]

The royal authority maintained the council,[217] most of the civic institutions,[66] and allowed the magistrates to be elected until 264.[214] Provincial governors continued to be appointed by Rome during Odaenathus' reign, but Palmyrene officials were appointed in the provinces to represent the king.[218] However, during the rebellion of Zenobia, the governors were appointed by the queen directly.[219] Not all Palmyrenes accepted the dominance of the royal family, a man with a senatorial rank named Septimius Haddudan, appears in one of the latest Palmyrene inscriptions as having aided the armies of Aurelian during the 273 rebellion.[220][221] Following the Roman destruction of the city, Palmyra lost its statehood and was ruled directly by the Romans,[222] and the following states (e.g. the Burids and Ayyubids),[123][223] or by subordinate Bedouin chiefs, mainly the Fadl family who ruled as governors for the Mamluks.[224]

Palmyrene military

The army was an important institution for Palmyra's protection and economy, it helped extend the Palmyrene authority beyond the city walls, and protected the countrysides, specially the desert trade routes.[225] Palmyra was able to amass substantial forces,[40] in the 3rd century BC, Zabdibel commanded a force of 10000,[33] and in the Battle of Emesa, Zenobia led an army of 70000 soldiers.[226] Those forces were recruited mostly from the city inhabitants, and the inhabitants of the Palmyrene territories, that spanned several thousand square kilometers stretching from the outskirts of Homs to the Euphrates valley.[40] Palmyra also recruited non Palmyrene soldiers, a Nabatean cavalryman is recorded in 132 as serving in a Palmyrene unit stationed at Anah.[226] The recruiting system is unknown, it is possible that the city selected and equipped the troops, while the many military generals (strategoi) led, trained and disciplined them.[227] The strategoi were appointed by the boule with the approval of Rome,[228] while the royal army was under the leadership of the monarch and the generals,[229][230] and modeled on the Sassanid style in regard to arms and tactics.[192] The Palmyrenes were famed as archers,[231] they utilized infantry,[232] and counted on the heavily armored cavalry (cataphract) as the main attack force.[233] Palmyrene infantry were armed with swords,[47] lances and small round shields, while the cataphract were fully armored including the horses, and used heavy spears (kontos) 3.65 centimeter in length without a shield.[234]

Relation with Rome

Citing their combating skills in large and sparsely populated areas, the Romans formed Palmyrene auxilia to serve in the Imperial Roman army.[47] Vaspasian reputedly had 8000 Palmyrene archers serving in Judea,[47] and Trajan established the first official Palmyrene auxilia in 116 (the camel cavalry unit, Ala I Ulpia dromedariorum Palmyrenorum).[47][235][236] Palmyrene units were deployed all around the Roman empire,[note 28] late in Hadrian's reign, Palmyrenes were serving in Dacia,[238] and during Antoninus Pius' reign, they served at El Kantara in Numidia and at Moesia.[238][239] Toward the end of the second century, Rome formed the Cohors XX Palmyrenorum, which was stationed in Dura-Europus.[238]

Rulers

.jpg)

| Ruler | Reigned | Title | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Odaenathus dynasty | ||||

| Odaenathus | 260-267 | King of kings | Posthumously described as king of kings, Odaenathus' inscriptions address him as king.[72] | |

| Hairan | 263-267 | King of kings | Son of Odaenathus, crowned by his father as co-king. Posthumously described as king of kings.[240] | |

| Maeonius | 267 | Emperor | Odaenathus' cousin.[80] | |

| Vaballathus | 267-272 | King of kings Emperor | Declared emperor in 271.[90] | |

| Zenobia | 267-272 | Queen of queens Empress | Declared empress in 271.[90] | |

| Antiochus | 273 | Emperor | According to an inscription, he was a relative and possible son of Zenobia.[221] | |

|

Al-Fadl | ||||

| Muhanna bin Issa | 1284-1293 | Prince | First reign, imprisoned by the Mamluks.[136] | |

| Muhanna bin Issa | 1295-1312 | Prince | Second reign.[136] | |

| Fadl bin Issa | 1312-1317 | Prince | Brother of Muhanna.[136] | |

| Muhanna bin Issa | 1317-1320 | Prince | Third reign, expelled with the whole tribe.[136] | |

| Muhanna bin Issa | 1330-1333 | Prince | Fourth reign.[136] | |

| Muzaffar al-Din Musa | 1333-1341 | Prince | Son of Muhanna.[241] | |

| Suleiman I | 1341-1342 | Prince | Son of Muhanna.[139] | |

| Sharaf al-Din Issa | 1342-1343 | Prince | Son of Fadl bin Issa.[139] | |

| Saif | 1343-1345 | Prince | Son of Fadl bin Issa.[139] | |

| Ahmad | 1345-1347 | Prince | Son of Muhanna.[242] | |

| Saif | 1347-1348 | Prince | Second reign.[242] | |

| Ahmad | 1348 | Prince | Second reign.[242] | |

| Fayad | 1348 | Prince | Son of Muhanna.[243] | |

| Hayar | 1348-1350 | Prince | Son of Muhanna.[243] | |

| Fayad | 1350-1361 | Prince | Second reign.[243] | |

| Hayar | 1361-1364 | Prince | Second reign, rebelled and was dismissed.[243][139] | |

| Zamil | 1364-1366 | Prince | Son of Musa the brother of Muhanna.[139] | |

| Hayar | 1366-1368 | Prince | Third reign, rebelled and was dismissed.[244] | |

| Zamil | 1368 | Prince | Second reign, rebelled and was dismissed.[244] | |

| Mu'ayqil | 1368-1373 | Prince | Son of Fadl bin Issa.[244] | |

| Hayar | 1373-1375 | Prince | Fourth reign.[244] | |

| Malik | 1375-1379 | Prince | Son of Muhanna.[244] | |

| Zamil | 1379-1380 | Prince | Third reign, co ruled with Mu'ayqil.[244] | |

| Mu'ayqil | 1379-1380 | Prince | Second reign, co ruled with Zamil.[244] | |

| Nu'air bin Hayar | 1380- | Prince | Son of Hayar.[244] | |

| Musa | -1396 | Prince | Son of Assaf the brother of Hayar.[244] | |

| Suleiman II | 1396-1398 | Prince | Son of 'Anqa the brother of Hayar.[245] | |

| Muhammad | 1398-1399 | Prince | Brother of Suleiman II.[246] | |

| Nu'air bin Hayar | 1399-1406 | Prince | Second reign.[246] | |

Religion

The Palmyrene deities belonged mostly to the Northwest Semitic pantheon, in addition to the Mesopotamian and Arab pantheons.[247] The city's pre-Hellenistic chief deity was Bol,[248] whose name is an abbreviation of Baal, the Northwest Semitic title for chief deity.[249] Due to the influence of the Babylonian cult of Bel Marduk,[248] Bol's name became Bel, however, the change did not indicate the replacing of Bol with a Mesopotamian deity, but was a mere change in the name.[249] Placed second in importance after the supreme deity, were the ancestral gods of the different Palmyrene clans,[250] and they included more than sixty deities.[251] Palmyra had its unique deities;[252] the justice god and Efqa's guardian Yarhibol,[253][254] the sun god Malakbel,[255] and the moon god Aglibol.[255] In addition, Palmyrenes worshiped regional deities; the wider Syrian Astarte, Baal-hamon, Baalshamin and Atargatis,[252] the Babylonian Nabu and Nergal,[252] and the Arab Azizos, Arsu, Šams and Al-lāt.[253][252]

The Palmyrene pantheon included a group of lesser deities named the ginnaye, that were prominent in the countrysides,[256] and had similarities with both the Arab jinn and the Roman genius.[257] ginnaye were believed to have the appearance and behavior of humans which is similar to the Arab jinn.[257] However, the ginnaye unlike the jinn, did not possess or hurt the humans,[257] but had a role similar to the genius, they were Tutelary deities who guarded the people, their caravans, cattle and villages.[257][250]

The Palmyrenes worshiped each deity individually, but also associated some of them with other gods.[258] Bel had Astarte-Belti as his consort, and formed a triad with Aglibol and Yarhibol who became a sun god in his association with Bel.[253][259] Malakbel was present in many of the associations,[258] he formed a pair with Aglibol,[260] a pair with Gad Taimi,[260] and a triad with Baalshamin and Aglibol.[261] Palmyra held the Akitu (spring) festival every Nisan.[262] Each of the four quarters of the city included a sanctuary for a deity that is considered ancestral to the tribe that resided in it, the pair Malakbel and Aglibol had their sanctuary in the Komare's quarter.[263] Baalshamin sanctuary was located in the he Ma'zin's quarter, Arsu in the Mattabol's quarter,[263] and Atargatis in the fourth tribe's quarter.[note 29][261]

With the spreading of Christianity across the Roman empire, Palmyra's pagan religion was replaced and a bishop is attested in the city by 325.[106] Most of the temples were turned into churches, while the temple of Al-lāt was destroyed in 385, by the orders of Maternus Cynegius, the Praetorian prefect of the East.[106] Following the Arab conquest in 634, Islam gradually replaced Christianity and the last attested bishop of Palmyra was consecrated in 818.[172]

Economy

Palmyra's economy before and at the beginning of the Roman period was based on agriculture, pastoralism, minor trade,[9] and acting as a rest station for caravans that sporadically crossed the desert road.[38] By the end of the first century BC, Palmyra had a mixed economy based on agriculture, pastoralism,[264] taxation,[265] and most importantly, caravan trade.[266]

Taxation provided an important source of income for the city.[265] Caravaneers paid the taxes in a building named the Tariff Court,[267] where the Palmyrene tax law dated to 137 was discovered.[268] The law regulated the different tariffs that the merchants had to pay in regard to the articles meant for the internal market.[267] Most of the lands were possessed by the city, which collected grazing taxes on its lands.[264] The oasis had approximately 1000 hectares of irrigable land,[269] in addition to the lands of the countrysides. However, the agriculture was not enough to support the population and food had to be imported.[270]

Following the destruction of 273, Palmyra became a market for villagers and nomads from the surrounding areas,[271] and the city regained some of its old prosperity during the Ummayad era, evident by the discovering of a big Ummayad Souq located in the colonnade street.[272] Palmyra continued as a minor trading center,[140] until the Timurid destruction,[144] which reduced it into a settlement on the borders of the desert, with the inhabitants living off herding and cultivating a small area to acquire vegetables and corn.[273]

Palmyrene caravan trade

The main trade route started in Palmyra and headed east to the Euphrates, where it connected to the Silk Road.[274] Then the route descended south along the river toward the port of Charax Spasinu on the Persian Gulf, where Palmyrene ships made the journey to India and back.[275] The merchandise were imported from India, China and Transoxiana,[276] then exported west to Emesa or Antioch, and afterward to the Mediterranean ports,[277] where they were transported to the different regions of the Roman empire.[275] In addition to the traditional route, some Palmyrene merchants used the Red Sea route,[276] probably as a result of the insecurities caused by the Parthian-Roman wars.[278] The merchandise would be carried from the Sea ports by land to one of the Nile ports, and then taken to the Egyptian Mediterranean ports to be exported.[278] Inscriptions that attests the Palmyrene existence in Egypt goes back as early as Hadrian's reign.[279]

As Palmyra was not situated on the traditional Silk Road, which followed the Euphrates,[9] the Palmyrenes secured the desert route that passed their city and connected it to the Euphrates valley, and provided it with watering and sheltering points.[9] The Palmyrene route was used almost exclusively by Palmyrene merchants,[9] who expanded and maintained a presence in many cities, including Dura-Europos in 33 BC,[49] Babylon (by 19 AD), Seleucia (by 24 AD),[42] and afterward in Dendera, Coptos,[280] Bahrain, the Indus River Delta, Merv and Rome among others.[281]

The caravan trade counted on patrons and merchants, the patrons were the owners of the lands on which the animals for the caravans were raised, and they provided the animals and guards for the merchants.[282] The merchants used the service of the patrons to conduct their business, however, the role of a merchant and a patron often overlapped, as the patron himself would sometimes lead the caravans.[282] The trade turned the city into one of the richest in the region,[266] and made the Palmyrene merchants extremely wealthy, some caravans were financed by a single merchant,[267] such as Male' Agrippa who paid the entire cost of emperor Hadrian's visit in 129, and financed the rebuilding of Bel's temple in 139.[53] The main income generating article of trade was silk, which was brought from the east and exported to the west.[283] Other goods transited and exported includes jade, muslin, spices, ebony, ivory and precious stones.[281] For its internal markets,[265] Palmyra imported slaves, prostitutes, olive oil, dyed goods, myrrh and perfumes.[265][281]

Scheme and excavation

Palmyra started as a small settlement near the Efqa spring on the southern bank of Wadi al-Qubur.[284] This settlement is named the Hellenistic settlement, and it contained residence quarters that expanded to the northern bank of the Wadi in the first century.[6] The walls of the city enclosed an extensive area on both banks of the wadi, while the walls rebuilt during Diocletian's era surrounded only the northern bank's sections.[6]

Most of the city's monumental projects were built on the northern bank of the wadi.[285] The temple of Bel is also located on the northern bank, on a tell which was the site of an earlier temple named the Hellenistic temple.[35] However, excavations support the theory that the temple was originally located on the southern bank, and that the wadi's bed was diverted, in order to incorporate Bel's temple into the new urban organization of the city, which started with the prosperity of the late first century and early second century.[34]

Also located north of the wadi, was the Great Colonnade, Palmyra's 1.1 km (0.68 mi) long main street,[286] that extended from Bel's temple in the east,[287] to the Funerary temple in the western end of the city.[288] It has a monumental arch in its eastern section,[289] and in the middle of it stands a Tetrapylon.[18]

On the left side of the colonnade, the so called Diocletian baths were located,[290] and they were built on the ruins of an earlier building which might have served as the royal palace.[180] Also built on the left side of the colonnade were the temple of Baalshamin,[291] residential quarters,[292] and the Byzantine churches which includes a 1,500-year-old church, the fourth in the city and believed to be the largest ever discovered in Syria.[2] The church columns were estimated to be 6 meters tall, and the base measured 12 meters by 24 meters.[2] A small Amphitheatre was found in the church's courtyard.[2]

On the southern side of the colonnade, the temple of Nabu and the Roman theater were built.[293] Behind the theater were located a small senate building and the large Agora, with remains of a banquet room (Triclinium) and the Tariff Court.[294] A transverse colonnade street at the western end of the colonnade leads to Diocletian's Camp,[286][295] which was built by the Roman governor of Syria, Sosianus Hierocles.[296] Nearby are the temple of Al-lāt (2nd century AD) and the Damascus Gate.[297]

Outside the ancient walls, to the west, the Palmyrenes constructed a series of large-scale funerary monuments which now form the so-called Valley of Tombs,[298] a 1 km (0.62 mi) long necropolis.[299] The monuments numbered more than 50 and were mostly in the shape of towers reaching up to four levels.[300] The city included other cemeteries in the north, southwest and southeast, where the tombs are mostly in the shape of a Hypogeum (underground tombs).[301][302]

Excavations

During the Middle Ages, the city was largely forgotten in the West.[148] It was sporadically visited by travelers such as Pietro Della Valle (between 1616-1625), Jean-Baptiste Tavernier (in 1638), in addition to many Swedish and German explorers.[303] In 1678, a group of English merchants visited the city, while the first scholarly description of it appeared in a book by Abednego Seller (1705).[303] In 1751, an expedition led by Robert Wood and James Dawkins studied the architecture of the city,[303] and visits by different travelers and antiquarians continued, including one by Lady Hester Stanhope in 1813.[303]

The first excavations were conducted in 1902 by Otto Puchstein, followed in 1917 by Theodor Wiegand.[162] In 1929, the French general director of antiquities of Syria and Lebanon Henri Arnold Seyrig, started a wide scale excavation in the site,[162] which was halted by the WW2, but resumed soon after its end.[162] Between 1954 and 1956, the temple of Baalshamin was excavated by a Swiss expedition organized by the UNESCO.[162] Since 1958, the site was excavated by the Syrian Directorate-General of Antiquities,[161] in addition to Polish expeditions led by Kazimierz Michałowski (until 1980) and Michael Gawlikowski (until 1984).[162]

In November 2010, Austrian media manager Helmut Thoma admitted to looting a Palmyrene grave in 1980, where he had stolen architectural pieces, today presented in his private living room.[304] German and Austrian archaeologists protested against this crime.[305]

Current situation

As a result of the Syrian Civil War, the site was subjected to wide scale looting and damaged by the clashes between the combatants.[306] In the summer of 2012, there was an increasing concern of looting of the museum and the site, when an amateur video was posted, showing Syrian soldiers carrying funerary stones.[307] However, according to France 24's report; "from the information gathered, it is impossible to determine whether pillaging was taking place."[307] In 2013, Bel's temple facade had a large circle caused by a mortar bomb, and the columns of colonnade have been damaged by shrapnel.[306] According to Maamoun Abdulkarim, the director of antiquities and museums at the Syrian Ministry of Culture, the Syrian Army positioned its troops in some of the archaeological site's areas,[306] while the Syrian opposition soldiers are stationed in the gardens around the city.[306]

See also

- Zabdas

- Aureliano in Palmira

- Palmyrene (Unicode block)

- Thirty Tyrants (Roman)

- Crisis of the Third Century

Notes

- ↑ Pliny mentioned that Palmyra was independent, but by 70 AD, Palmyra was part of the Roman empire and Pliny's account over Palmyra's political situation is dismissed by modern scholars, as it is considered to rely on older accounts, dating to the period of Octavian, when Palmyra was independent.[8]

- ↑ The Semitic word T.M.R is the common root for the words that designate palm dates in Arabic, Hebrew, Ge'ez and other Semitic languages.[11]

- ↑ The Hebrew Bible mentions Tadmor as a city built by Solomon, Schultens' argued that it is written Tamor, and in the margin Tadmor.[12] Schultens considered Tamor to be derived from Tamar,[12] however, the inclusion of a -d- in Tamar can not be explained.[4]

- ↑ According to Schultens, the Romans altered the name from Tadmor to Talmura, and afterward to Palmura (from the Latin word palma, meaning palm),[10] in reference to the palm trees. Then the name reached its final form Palmyra.[14]

- ↑ The name could be a translation of Tadmor (assuming that it meant palm), and derived from the Greek word (Palame).[4]

- ↑ Zabdibel is not explicitly identified as a Palmyrene, however, this name is only attested in Palmyra.[32]

- ↑ No evidence for Germanicus visiting Palmyra exist.[41]

- ↑ The legion was part of Germanicus' eastern campaign and was not stationed in the city as a garrison.[43]

- ↑ Commissioned by Traianus.[46]

- ↑ The transformation already began in the first century BC.[49]

- ↑ Although a mainstream view that Palmyra benefited from Petra's annexation, it should be noted that Palmyra's trade was mostly with the east, while Petra's trade counted on southern Arabia. In addition to the fact that Palmyra's articles of trade were different from Petra, hence the annexation of Petra might have not had a real effect on Palmyra's trade.[52]

- ↑ Odaenathus' rise process is ambiguous, he belonged to the mercantile elite, and might have been elected as chief by the council of the city.[65]

- ↑ The first decisive evidence for the use of this title is an inscription dated to 271, posthumously describing Odaenathus as king of kings.[72][67] However, Odaenathus' own inscriptions address him as king, and it is not certain that he used the king of kings title.[72]

- ↑ Claudius died in August 270, shortly before Zenobia's invasion of Egypt.[86]

- ↑ Scholarly is divided whether this was an act of independence declaration, or a usurpation of the Roman throne.[92][93][94]

- ↑ All other accounts indicate that a military action was not necessary, as it seems that Zenobia's withdrawn her forces in order to defend Syria.[96]

- ↑ The Salyane Sanjak had an annual allowance from the government, in contrast to the Khas Sanjaks, which yielded a land revenue.[147]

- ↑ The British did not occupy the area and the local Bedouins agreed to protect the field.[155]

- ↑ Neither the British, French or Arab armies attacked the Sanjak.[157]

- ↑ E.g. Gaddibol and Yedi'bel.[180]

- ↑ E.g. Bene Ma'zin.[180]

- ↑ E.g. for Amorite: Zmr' and Kohen-Nadu.[180]

- ↑ The Bene Mita, Komare, Mattabol, Ma'zin and Claudia.[183]

- ↑ In general, a civic tribe (Phyle) is a collection of people chosen from the collective population and ascribed a deity as a tribal ancestor, then assigned a territory for them to reside in. The Phyles were united by their citizenship instead of origin.[186]

- ↑ E.g. by the second century, Palmyrene goddess Al-lāt was portrayed in the style of the Greek goddess Athena, and named Athena-Al-lāt. However, this assimilation of Al-lāt to Athena did not extend beyond iconography.[189]

- ↑ In the Hellenistic tradition, The Agora was the center of athletic, artistic, spiritual and political life of the city.[194]

- ↑ The number is hypothetical.[213]

- ↑ A Palmyrene monument was discovered near Newcastle in England, it was set by a Palmyrene named Baratas, who was either a soldier or a camp follower.[237]

- ↑ The fourth tribe's name is not certain but most likely the Mita.[261]

References

Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Trevor Bryce (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. p. 280.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "Syria uncovers 'largest church'". BBC News. 2008. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ↑ Richard Stoneman (1994). Palmyra and Its Empire: Zenobia's Revolt Against Rome. p. 56.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Yoël L. Arbeitman (1988). A Linguistic Happening in Memory of Ben Schwartz: Studies in Anatolian, Italic, and Other Indo-European Languages. p. 235.

- ↑ Direction générale des antiquités et des musées, République arabe syrienne (1996). Annales archéologiques Arabes Syriennes, Volume 42 (in Arabic). p. 246.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Hartmut Kühne, Rainer Maria Czichon, Florian Janoscha Kreppner (2008). Proceedings of the 4th International Congress of the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, 29 March - 3 April 2004, Freie Universität Berlin: The reconstruction of environment : natural resources and human interrelations through time ; art history : visual communication. p. 229.

- ↑ Lucinda Dirven (1999). The Palmyrenes of Dura-Europos: A Study of Religious Interaction in Roman Syria. p. 17.

- ↑ Peter Edwell (2007). Between Rome and Persia: The Middle Euphrates, Mesopotamia and Palmyra under Roman control. p. 73.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 Gary K. Young (2003). Rome's Eastern Trade: International Commerce and Imperial Policy 31 BC - AD 305. p. 124.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Yoël L. Arbeitman (1988). A Linguistic Happening in Memory of Ben Schwartz: Studies in Anatolian, Italic, and Other Indo-European Languages. p. 238.

- ↑ A. Murtonen (1989). Hebrew in Its West Semitic Setting: A Comparative Survey of Non-Masoretic Hebrew Dialects and Traditions, Deel 1. p. 445.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Richard Stephen Charnock (1859). Local Etymology: A Derivative Dictionary of Geographical Names. p. 200.

- ↑ Yoël L. Arbeitman (1988). A Linguistic Happening in Memory of Ben Schwartz: Studies in Anatolian, Italic, and Other Indo-European Languages. p. 248.

- ↑ Richard Stephen Charnock (1859). Local Etymology: A Derivative Dictionary of Geographical Names. p. 201.

- ↑ Yoël L. Arbeitman (1988). A Linguistic Happening in Memory of Ben Schwartz: Studies in Anatolian, Italic, and Other Indo-European Languages. p. 236.

- ↑ Pat Southern (2008). Empress Zenobia: Palmyra s Rebel Queen. p. 18.

- ↑ Trudy Ring,Robert M. Salkin,Sharon La Boda (1996). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Middle East and Africa, Volume 4. p. 565.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Simon Hornblower, Antony Spawforth, Esther Eidinow (2014). The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization. p. 566.

- ↑ Shiruku Rōdo-gaku Kenkyū Sentā (1995). Space archaeology. p. 19.

- ↑ Malcolm A. R. Colledge (1976). The Art of Palmyra. p. 11.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Michael Dumper,Bruce E. Stanley (2007). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. p. 293.

- ↑ Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies (1998). The Journal of Roman Studies, Volumes 40-42. p. 1.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Lucinda Dirven (1999). The Palmyrenes of Dura-Europos: A Study of Religious Interaction in Roman Syria. p. 18.

- ↑ Mario Liverani (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. p. 234.

- ↑ Michelle Makdesi, Ma'mun Abd al-Karim (2002). al-Jazīrah al-Sūrīyah, al-turāth al-ḥaḍārī wa-al-ṣilāt al-mutabādalah: waqāʼiʻ al-muʼtamar al-duwalī, Dayr al-Zūr 22-25 Nīsān 1996. p. 325.

- ↑ Charles Knight (1840). The Penny Cyclopaedia of the Society for the Difussion of Useful Knowledge, Volume 17. p. 175.

- ↑ Isidore Epstein (1984). Hebrew-English Edition of the Babylonian Talmud: Yebamoth. p. 194.

- ↑ Fergus Millar (1993). The Roman Near East, 31 B.C.-A.D. 337. p. 320.

- ↑ Phillip K. Hitti (2004). History of Syria, Including Lebanon and Palestine. p. 389.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 Trevor Bryce (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. p. 276.

- ↑ Richard Stoneman (1994). Palmyra and Its Empire: Zenobia's Revolt Against Rome. p. 52.

- ↑ Trevor Bryce (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. p. 359.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 33.5 33.6 33.7 33.8 Trevor Bryce (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. p. 278.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Hartmut Kühne, Rainer Maria Czichon, Florian Janoscha Kreppner (2008). Proceedings of the 4th International Congress of the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, 29 March - 3 April 2004, Freie Universität Berlin: The reconstruction of environment : natural resources and human interrelations through time ; art history : visual communication. p. 231.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Andrew M. Smith II (2013). Roman Palmyra: Identity, Community, and State Formation. p. 63.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Hugh Elton (2013). Frontiers of the Roman Empire. p. 90.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 Lucinda Dirven (1999). The Palmyrenes of Dura-Europos: A Study of Religious Interaction in Roman Syria. p. 19.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Warwick Ball (2002). Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire. p. 74.

- ↑ Peter Edwell (2007). Between Rome and Persia: The Middle Euphrates, Mesopotamia and Palmyra under Roman control. p. 70.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 Trevor Bryce (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. p. 284.

- ↑ Andrew M. Smith II (2013). Roman Palmyra: Identity, Community, and State Formation. p. 24.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 Lucinda Dirven (1999). The Palmyrenes of Dura-Europos: A Study of Religious Interaction in Roman Syria. p. 20.

- ↑ Edward Dąbrowa (1993). Legio X Fretensis. p. 12.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Hildegard Temporini (1978). Politische Geschichte: (Provinzien und Randvölker: Mesopotamien, Armenien, Iran, Südarabien, Rom und der Ferne Osten), Deel 2,Volume 9. p. 769.

- ↑ Hugh Elton (2013). Frontiers of the Roman Empire. p. 91.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 Hugh Elton (2013). Frontiers of the Roman Empire. p. 92.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 47.3 47.4 Pat Southern (2008). Empress Zenobia: Palmyra's Rebel Queen. p. 25.

- ↑ Fergus Millar (1993). The Roman Near East, 31 B.C.-A.D. 337. p. 323.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Peter Edwell (2007). Between Rome and Persia: The Middle Euphrates, Mesopotamia and Palmyra under Roman control. p. 64.

- ↑ Lucinda Dirven (1999). The Palmyrenes of Dura-Europos: A Study of Religious Interaction in Roman Syria. p. 22.

- ↑ Andrew M. Smith II (2013). Roman Palmyra: Identity, Community, and State Formation. p. 145.

- ↑ Gary K. Young (2003). Rome's Eastern Trade: International Commerce and Imperial Policy 31 BC - AD 305. p. 125.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Trevor Bryce (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. p. 279.

- ↑ Lucinda Dirven (1999). The Palmyrenes of Dura-Europos: A Study of Religious Interaction in Roman Syria. p. 21.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 Andrew M. Smith II (2013). Roman Palmyra: Identity, Community, and State Formation. p. 25.

- ↑ Hildegard Temporini (1978). Politische Geschichte: (Provinzien und Randvölker: Mesopotamien, Armenien, Iran, Südarabien, Rom und der Ferne Osten), Part 2,Volume 9. p. 881.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 Alan Bowman,Peter Garnsey,Averil Cameron (2005). The Cambridge Ancient History: Volume 12, The Crisis of Empire, AD 193-337. p. 512.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 58.2 Andrew M. Smith II (2013). Roman Palmyra: Identity, Community, and State Formation. p. 26.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 59.2 59.3 Andrew M. Smith II (2013). Roman Palmyra: Identity, Community, and State Formation. p. 28.

- ↑ Peter Edwell (2007). Between Rome and Persia: The Middle Euphrates, Mesopotamia and Palmyra Under Roman Control. p. 60.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 61.2 Peter Edwell (2007). Between Rome and Persia: The Middle Euphrates, Mesopotamia and Palmyra Under Roman Control. p. 62.

- ↑ Peter Edwell (2007). Between Rome and Persia: The Middle Euphrates, Mesopotamia and Palmyra Under Roman Control. p. 61.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Andrew M. Smith II (2013). Roman Palmyra: Identity, Community, and State Formation. p. 176.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.2 64.3 64.4 Andrew M. Smith II (2013). Roman Palmyra: Identity, Community, and State Formation. p. 29.

- ↑ Warwick Ball (2002). Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire. p. 77.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 66.2 66.3 66.4 66.5 Andrew M. Smith II (2013). Roman Palmyra: Identity, Community, and State Formation. p. 131.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Andrew M. Smith II (2013). Roman Palmyra: Identity, Community, and State Formation. p. 177.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 68.2 68.3 68.4 68.5 68.6 David L. Vagi (2000). Coinage and History of the Roman Empire, C. 82 B.C.--A.D. 480: History. p. 398.

- ↑ Trevor Bryce (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. p. 287.

- ↑ Trevor Bryce (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. p. 290.

- ↑ Nathanael J. Andrade (2013). Syrian Identity in the Greco-Roman World. p. 333.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 72.2 Richard Stoneman (1994). Palmyra and Its Empire: Zenobia's Revolt Against Rome. p. 78.

- ↑ Maurice Sartre (2005). The Middle East Under Rome. p. 354.

- ↑ Edward Gibbon (2004). The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. p. 501.

- ↑ Clifford Ando (2012). Imperial Rome AD 193 to 284: The Critical Century. p. 237.

- ↑ Nathanael John Andrade (2009). "Imitation Greeks": Being Syrian in the Greco-Roman World (175 BCE--275 CE). p. 404.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Lukas De Blois (1976). The Policy of the Emperor Gallienus. p. 3.

- ↑ Kaveh Farrokh,Angus McBride (2012). Sassanian Elite Cavalry AD 224-642. p. 46.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 Pat Southern (2008). Empress Zenobia: Palmyra s Rebel Queen. p. 78.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 Trevor Bryce (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. p. 292.

- ↑ Richard Stoneman (1994). Palmyra and Its Empire: Zenobia's Revolt Against Rome. p. 108.

- ↑ Edward Gibbon, Thomas Bowdler (1826). History of the decline and fall of the Roman empire for the use of families and young persons: reprinted from the original text, with the careful omission of all passagers of an irreligious tendency, Volume 1. p. 321.

- ↑ George C. Brauer (1975). The Age of the Soldier Emperors: Imperial Rome, A.D. 244-284. p. 163.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 84.2 Trevor Bryce (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. p. 299.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 Trevor Bryce (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. p. 302.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 Alaric Watson (2014). Aurelian and the Third Century. p. 62.

- ↑ Trevor Bryce (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. p. 303.

- ↑ Trevor Bryce (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. p. 304.

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 Warwick Ball (2002). Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire. p. 80.

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 90.2 90.3 Andrew M. Smith II (2013). Roman Palmyra: Identity, Community, and State Formation. p. 179.

- ↑ David L. Vagi (2000). Coinage and History of the Roman Empire, C. 82 B.C.--A.D. 480: History. p. 365.

- ↑ Warwick Ball (2002). Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire. p. 82.

- ↑ Chase F. Robinson (2010). The New Cambridge History of Islam: Volume 1, The Formation of the Islamic World, Sixth to Eleventh Centuries. p. 154.

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 Andrew M. Smith II (2013). Roman Palmyra: Identity, Community, and State Formation. p. 180.

- ↑ Trevor Bryce (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. p. 307.

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 Trevor Bryce (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. p. 308.

- ↑ Trevor Bryce (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. p. 309.

- ↑ Trevor Bryce (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. p. 310.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 99.2 Warwick Ball (2002). Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire. p. 81.

- ↑ Alan Bowman,Peter Garnsey,Averil Cameron (2005). The Cambridge Ancient History: Volume 12, The Crisis of Empire, AD 193-337. p. 52.

- ↑ Trevor Bryce (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. p. 313.

- ↑ Andrew M. Smith II (2013). Roman Palmyra: Identity, Community, and State Formation. p. 181.

- ↑ Alan Bowman,Peter Garnsey,Averil Cameron (2005). The Cambridge Ancient History: Volume 12, The Crisis of Empire, AD 193-337. p. 515.

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 104.2 Nigel Pollard (2000). Soldiers, Cities, and Civilians in Roman Syria. p. 298.

- ↑ Nigel Pollard (2000). Soldiers, Cities, and Civilians in Roman Syria. p. 299.

- ↑ 106.0 106.1 106.2 Richard Stoneman (1994). Palmyra and Its Empire: Zenobia's Revolt Against Rome. p. 190.

- ↑ 107.0 107.1 Geoffrey Greatrex,Samuel N. C. Lieu (2005). The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars AD 363-628. p. 85.

- ↑ 108.0 108.1 108.2 108.3 Trudy Ring,Noelle Watson,Paul Schellinger (2014). Middle East and Africa: International Dictionary of Historic Places. p. 568.

- ↑ Gian Pietro Brogiolo,Bryan Ward Perkins (1999). The Idea and Ideal of the Town Between Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. p. 87.

- ↑ Paul M. Cobb (2001). White Banners: Contention in 'Abbasid Syria, 750-880. p. 73.

- ↑ Paul M. Cobb (2001). White Banners: Contention in 'Abbasid Syria, 750-880. p. 47.

- ↑ 112.0 112.1 Paul M. Cobb (2001). White Banners: Contention in 'Abbasid Syria, 750-880. p. 48.

- ↑ P.M. Holt (2014). The Age of the Crusades: The Near East from the Eleventh Century to 1517. p. 13.

- ↑ J.B. Bury (2011). The Cambridge Medieval History Series volumes 1-5. p. 1531.

- ↑ Oleg Grabar,Reneta Holod,James Knustad,William Trousdale (1978). City in the Desert. p. 11.

- ↑ Oleg Grabar,Reneta Holod,James Knustad,William Trousdale (1978). City in the Desert. p. 158.

- ↑ ʻImād al-Dīn Mawṣīlī (1981). Rubu' Muḥafazet ḥoms (in Arabic). p. 221.

- ↑ Elizabeth Key Fowden (1999). The Barbarian Plain: Saint Sergius Between Rome and Iran. p. 184.

- ↑ Mahmud Hussein Amin (1998). Banu Mala'ib fel-Tarikh (in Arabic). p. 50.

- ↑ Youssef M. Choueiri (2008). A Companion to the History of the Middle East. p. 148.

- ↑ 121.0 121.1 Ibn al-ʻAdim (1261). Bughyat al-ṭalab fī tārīkh Ḥalab. Volume 3 (in Arabic). p. 365.

- ↑ Eric J. Hanne (2007). Putting the Caliph in His Place: Power, Authority, and the Late Abbasid Caliphate. p. 135.

- ↑ 123.0 123.1 123.2 123.3 H. A. R. Gibb (2012). The Damascus Chronicle of the Crusades: Extracted and Translated from the Chronicle of Ibn Al-Qalanisi. p. 178.

- ↑ 124.0 124.1 Abu Yala Hazma ibn Asad al-Tamini Ibn al-Qalanisi, H. F. Amedroz (1908). Tarikh Abu Yala Hamza Ibn al-Qalanisi al-maruf Bi-Dhail tarikh Dimashq: tatluh nukhab min tawarikh Ibn al-Azraq al-Fariqi wa-Sibt ibn al-Giawzi wa-l-Hafiz al-Dhahbi (in Arabic). p. 73.

- ↑ Oleg Grabar,Reneta Holod,James Knustad,William Trousdale (1978). City in the Desert. p. 161.

- ↑ 126.0 126.1 H. A. R. Gibb (2012). The Damascus Chronicle of the Crusades: Extracted and Translated from the Chronicle of Ibn Al-Qalanisi. p. 237.

- ↑ Muḥammad Ibn-Aḥmad ad̲- D̲ahabī (1338). Siyar aʻlām an-nubalā·, Volume 20 (in Arabic). p. 533.

- ↑ Institut français de Damas (1999). Bulletin d'études orientales, Volume 51. p. 161.

- ↑ Muḥammad Ibn-Aḥmad ad̲- D̲ahabī (1338). Siyar aʻlām an-nubalā·, Volume 20 (in Arabic). p. 430.

- ↑ Andrew S. Ehrenkreutz (1972). Saladin. p. 72.

- ↑ Abū al-Fidāʼ Ismāʻīl ibn ʻAlī (1331). Al-mukhtaṣar fī akhbār al-bashar, Volumes 1-2 (in Arabic). p. 349.

- ↑ R. Stephen Humphreys (1977). From Saladin to the Mongols: The Ayyubids of Damascus, 1193-1260. p. 51.

- ↑ Zsolt Hunyadi, József Laszlovszky (2001). The Crusades and the Military Orders: Expanding the Frontiers of Medieval Latin Christianity. p. 62.

- ↑ 134.0 134.1 Ross Burns (2009). Monuments of Syria: A Guide. p. 243.

- ↑ 135.0 135.1 R. Stephen Humphreys (1977). From Saladin to the Mongols: The Ayyubids of Damascus, 1193-1260. p. 360.

- ↑ 136.0 136.1 136.2 136.3 136.4 136.5 136.6 136.7 136.8 136.9 Khayr al-Dīn Ziriklī (1926). al-Aʻlām,: qāmūs tarājim al-ashʾhur al-rijāl wa-al-nisāʾ min al-ʻArab wa-al-mustaʻrabīn wa-al-mustashriqīn, Volume 7 (in Arabic). p. 73.

- ↑ David Nicolle (2005). Acre 1291: Bloody Sunset of the Crusader States. p. 30.

- ↑ Ibn Khaldūn (1375). Kitāb al-ʻibar wa-dīwān al-mubtadaʾ wa-al-khabar f̣ī ayyām al-ʻArab wa-al-ʻAjam ẉa-al-Barbar wa-man ʻāṣarahum min dhawī al-sulṭān al-al-akbar wa-huwa tarīkh waḥīd ʻaṣrih, Volume 5 (in Arabic). p. 104.

- ↑ 139.0 139.1 139.2 139.3 139.4 139.5 139.6 Ibn Khaldūn (1375). Kitāb al-ʻibar wa-dīwān al-mubtadaʾ wa-al-khabar f̣ī ayyām al-ʻArab wa-al-ʻAjam ẉa-al-Barbar wa-man ʻāṣarahum min dhawī al-sulṭān al-al-akbar wa-huwa tarīkh waḥīd ʻaṣrih, Volume 5 - Part 30 (in Arabic). p. 105.

- ↑ 140.0 140.1 Commission of the Arabic Encyclopedia (1998). al-Mawsūʻah al-ʻArabīyah (in Arabic). p. 230.

- ↑ Ibn Batuta (1355). Kitāb riḥlat Ibn Baṭūṭah al-musammāh Tuḥfat al-nuẓẓār fī gharāʾib al-amṣār wa-ʻajāʾib al-asfār (in Arabic). p. 79.

- ↑ Thomas Stewart Traill (1859). The Encyclopaedia Britannica: Or, Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and General Literature, Volume 17. p. 222.

- ↑ Henry Burgess (1856). A cyclopaedia of Biblical literature. p. 817.

- ↑ 144.0 144.1 David Moore Robinson (1946). Baalbek, Palmyra. p. 10.

- ↑ 145.0 145.1 Aḥmad ibn ʻAlī Ibn Ḥajar al-ʻAsqalānī (1446). Inbāʼ al-ghumr bi-abnāʼ al-ʻumr, Volume 5 (in Arabic). p. 349.

- ↑ Andrew Petersen (2002). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. p. 272.

- ↑ 147.0 147.1 Evliya Çelebi, Joseph Freiherr von Hammer-Purgstall (1834). Narrative of Travels in Europe, Asia, and Africa in the Seventeenth Century, Volume 1. p. 93.

- ↑ 148.0 148.1 148.2 M. Th.Houtsma, T.W.Arnold, R.Basset and R.Hartmann (1993). First Encyclopaedia of Islam: 1913-1936. p. 1021.

- ↑ Stefan Winter (2010). The Shiites of Lebanon under Ottoman Rule, 1516–1788. p. 43.

- ↑ Stefan Winter (2010). The Shiites of Lebanon under Ottoman Rule, 1516–1788. p. 48.

- ↑ 151.0 151.1 William Harris (2012). Lebanon: A History, 600-2011. p. 103.

- ↑ Michal Gawlikowski and Wiktor A. Daszewski (1995). Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean, Volume 7. p. 146.

- ↑ Hugh Chisholm (1910). The Encyclopædia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information, Volume 7. p. 933.

- ↑ David Kennedy,Derrick Riley (2012). Romes Desert Frontiers. p. 143.

- ↑ 155.0 155.1 155.2 155.3 155.4 John D. Grainger (2013). The Battle for Syria, 1918-1920. p. 228.

- ↑ Alan Warwick Palmer (2000). Victory 1918. p. 235.

- ↑ 157.0 157.1 Zubair Sultan Qadduri (2000). Athawra al-Manseya (in Arabic). p. 50.

- ↑ Zubair Sultan Qadduri (2000). Athawra al-Manseya (in Arabic). p. 51.

- ↑ Daniel Neep (2012). Occupying Syria Under the French Mandate: Insurgency, Space and State Formation. p. 28.

- ↑ Daniel Neep (2012). Occupying Syria Under the French Mandate: Insurgency, Space and State Formation. p. 142.

- ↑ 161.0 161.1 161.2 Diana Darke (2010). Syria. p. 257.

- ↑ 162.0 162.1 162.2 162.3 162.4 162.5 162.6 Richard Stoneman (1994). Palmyra and Its Empire: Zenobia's Revolt Against Rome. p. 12.

- ↑ H. T. Bakker (1987). Iconography of Religions. p. 4.

- ↑ William W. Cotterman (2013). Improbable Women: Five who Explored the Middle East. p. 5.

- ↑ Jules Janick (2012). Horticultural Reviews, Horticultural Reviews. p. 26.

- ↑ Bruce Manning Metzger,Michael D. Coogan,Michael David Coogan (2004). The Oxford Guide to People & Places of the Bible. p. 17.

- ↑ William W. Cotterman (2013). Improbable Women: Five who Explored the Middle East. p. 4.

- ↑ C. H. M. Versteegh,Kees Versteegh (2001). The Arabic Language. p. 29.

- ↑ Christoph Luxenberg (2007). The Syro-Aramaic Reading of the Koran: A Contribution to the Decoding of the Language of the Koran. p. 11.

- ↑ Delbert R. Hillers,Eleonora Cussini (2005). A Journey to Palmyra: Collected Essays to Remember Delbert R. Hillers. p. 209.

- ↑ Irfan Shahid (1995). Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, Volume 1. p. 438.

- ↑ 172.0 172.1 Irfan Shahid (1995). Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, Volume 1. p. 439.

- ↑ Richard Stoneman (1994). Palmyra and Its Empire: Zenobia's Revolt Against Rome. p. 192.

- ↑ John Kitto (1837). The Pictorial Bible, Being the Old and New Testaments, Volume 2. p. 341.

- ↑ F. P. Lock (2012). The Rhetoric of Numbers in Gibbon's History. p. 86.

- ↑ Klaus Beyer (1986). The Aramaic Language, Its Distribution and Subdivisions. p. 28.

- ↑ John F. Healey (1990). The Early Alphabet. p. 46.

- ↑ 178.0 178.1 Charles Albert Ferguson (1997). Structuralist Studies in Arabic Linguistics: Charles A. Ferguson's Papers, 1954-1994. p. 21.

- ↑ Javier Teixidor (1979). The Pantheon of Palmyra. p. 9.

- ↑ 180.0 180.1 180.2 180.3 180.4 Richard Stoneman (1994). Palmyra and Its Empire: Zenobia's Revolt Against Rome. p. 67.

- ↑ Delbert R. Hillers,Eleonora Cussini (2005). A Journey to Palmyra: Collected Essays to Remember Delbert R. Hillers. p. 195.

- ↑ Andrew M. Smith II (2013). Roman Palmyra: Identity, Community, and State Formation. p. 38.