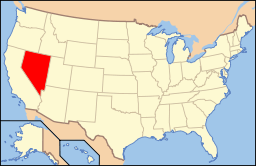

Paleontology in Nevada

Paleontology in Nevada refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Nevada. Nevada has a rich fossil record of plants as well as both invertebrate and vertebrate animal life.[1] During the Late Precambrian eastern and southern Nevada was being gradually covered by a shallow sea that was home to blue-green bacteria. During the early Paleozoic a variety of local aquatic invertebrates inhabited both freshwater (molluscs) and salt water (graptolites). By the Carboniferous reefs formed despite a drop in local sea levels and a variety of plants flourished on land.

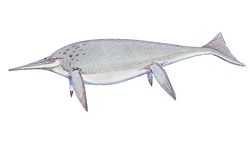

Sea levels continued to drop into the early Mesozoic although ammonites and ichthyosaurs inhabited regions still submerged by the sea. Sea levels continued to drop through the Jurassic. An island chain where Sequoia trees grew emerged during the Cretaceous, but little else is known. Woodlands covered the state during the early part of the Cenozoic era. The state would come to be home to camels, horses, mammoths, and giant ground sloths. Local Native Americans devised myths to explain fossils. By the late 19th century local fossils had attracted the attention of formally trained scientists. Nevertheless, very little organized paleontology has been done within Nevada, and much of that has been carried on by out of state researchers. Consequently, there are few fossils displayed within Nevada. Among the institutions that do house fossils within the state is the Nevada State Museum, Las Vegas.[2] The Triassic ichthyosaur Shonisaurus popularis is the Nevada state fossil.[3]

Prehistory

During the Late Precambrian eastern and southern Nevada was being gradually covered by a shallow sea. Blue-green bacteria from this time period were preserved in those areas of the state.[4] More than 500 kinds of Paleozoic invertebrates are known to have inhabited Nevada during the Cambrian, Devonian, and Carboniferous periods of the Paleozoic era. Most of the invertebrates known from this time were freshwater mollusks.[1] The sea continued to expand into the state through the Devonian. During that period northwestern Nevada's sea began to get deeper, gradually becoming an ocean basin. These deeper water areas of Devonian Nevada were home to drifting animals like graptolites. The shallower water regions were home to reefs. Near the end of the Devonian an interval of mountain building called the Antler Orogeny began.[4] The Antler Orogeny continued into the Early Carboniferous. Dropping sea levels exposed regions of Nevada as dry land. Environments of eastern Nevada included lagoons and beaches. Local plant life were preserved in rocks formed by these deposits. Northern and northeastern Nevada were still home to reef habitats. Northwestern Nevada was still a deep ocean. Its abundant plankton left behind many fossils.[4]

Nevada's sea level continued to drop during the Triassic period. However, the western part of the state was still relatively deep. It was home to a rich ammonite and ichthyosaur fauna.[4] During the Triassic, many invertebrates lived and died in the area now occupied by the Shoshone Mountains. Their fossils are scientifically significant as many are now used as index fossils or were completely unknown to science before their discovery here.[5] By the Jurassic, the only deep marine habitats of Nevada were in the northwestern part of the state. Central Nevada was only under shallow water and the eastern and southern parts of the state were characterized by other types of environment.[4] During the Cretaceous, a volcanic island chain formed in far western Nevada. Contemporary plant fossils from Nevada include "twigs" of petrified wood preserved in Eureka County. These may be the remnants of ancient Sequoia trees.[4] Local dinosaurs included armored dinosaurs, possible duck-billed dinosaurs and relatives of the horned dinosaurs.[6]

During the Cenozoic geologic upheaval created the state's basin and range physiographic province. Woodlands harboring trees like oak, redwood, and willow formed in Nevada. Local wildlife included creatures like horses, mammoths, and rhinos. Volcanic eruptions regularly shook the state during the Cenozoic.[4] Some of Nevada's Miocene life was preserved in the sediments composing what are now known as the Truckie Beds of the Kawich Mountains northeast of modern Reno. Local bodies of fresh water were inhabited by mollusks at the time. On land Nevada was home to a variety of mammals including both mastodons and rhinoceroses.[7] As the Cenozoic continued, Nevada's Sierra Nevada Mountains were raised. Volcanic activity was still ongoing. Local wildlife included camels, horses, mammoths, and giant ground sloths.[4] Nevada's trace fossil record from the Pleistocene is very rich. One site preserved the footprints of a diverse menagerie of creatures including birds, giant sloths, horses, lions, mastodons, and wolves.[8]

History

Indigenous interpretations

The Paiute people of northwestern Nevada believe that the region around Lovelock was once home to a race of red haired cannibals they called the Si-Teh-Cahs.[9] The ancestral Paiutes supposedly killed the Si-Teh-Cahs by trapping them in Lovelock Cave and lighting a huge fire to smother them with the smoke. When the Paiutes returned to the cave, it smelt of their burnt remains. Some of the details in the story correspond with the physical details of Lovelock cave. The cave does preserve evidence for ancient fires and the cave's deep bat guano smells comparable to burnt human remains. Red-haired human mummies were also found in the cave. These were wildly promoted by some white people as being giants, but at least some versions of the story of the Si-Teh-Cahs portray them as normal sized. The mummies, of course, were not actually giants. Nevertheless, it's possible that some versions of the Paiute legend of the Si-Teh-Cahs described them as giants based on the limb bones of cave bears and mammoths, which are both human-like and common in the Black Rock Desert Area.[10] The depiction of the Si-Teh-Cahs as red-haired likely derives from the red hair of the mummies, however it should be noted that darkly colored hair contains unstable pigments that break down over time leaving the hair a reddish color.[11] This belief may have been influenced by the 2,000 year old human mummies in the cave and the cave bear and mammoth fossils found north of Lovelock Cave.[9]

There is additional evidence for knowledge of fossils among local indigenous peoples. The Paiute and Ute people of Nevada were aware of dinosaur footprints in addition to their fossil-derived myths about the Si-Teh-Cahs.[12] Fossil teratorn remains found in Nevada may have helped inspire other local beliefs in monstrous birds.[13]

Scientific research

The first serious paleontological field work in Nevada prospected for fossils in the Eureka area. Their field site was perched at an altitude of 6,000 feet and lay between the basins of Lake Bonneville and Lake Lahontan. Excavators discovered more than 500 kinds of Paleozoic invertebrates from the Cambrian, Devonian, and Carboniferous periods. Most of the animals uncovered were freshwater mollusks. A significant proportion were previously unknown to science.[1] Another significant early fossil discovery in Nevada happened entirely serendipitously. Around the time of the Gold Rush, the gaol in Carson City needed more room. The sandstone walls were blasted to create material for constructing a workshop. The blasting revealed a variety of fossil footprints. In 1882 paleontologists from the National Academy of Sciences identified the tracks as belonging to Pleistocene creatures like birds, horses, lions, mastodons, giant sloths, and wolves.[8]

Early in 1900 a new Nevada fossil site was discovered in the Virgin Valley. The site bore three fossil rich horizons. The lower and upper layers were rich in animal remains like two relatives of modern camels, a large cat, two different kinds of horse, remains likely belonging to a rhinoceros, and mastodons. Between the animal-bearing layer was a deposit rich in plant material like leaves, logs, and stems. In 1908 more discoveries were made in the Virgin Valley area in beds being exploited for opal. There naturally occurring casts of twigs, limbs, and cracks of petrified wood were found.[1] In 1912 a slab of rock preserving fish, a primitive horse, mollusks, and plants, near Esmeralda Field.[14] In 1914, Miocene fossils of creatures like freshwater mollusks, mastodons, and rhinoceros were found in the Kawich Mountains northeast of Reno. The site is now known as the Truckie Beds. In 1930 M. R. Harrington was searching for Pueblo Indian pottery when he serendipitously discovered the skull of a ground sloth in Gypsum Cave in southern Nevada. Harrington later returned to the site and uncovered more of the sloth's bones.[7]

In 1933, the Tule Springs Expedition, led by Fenley Hunter, was the first major effort to explore the archaeological importance of the area surrounding Tule Springs. The Tule Springs Archaeological Site contains ground sloths, mammoths, prehistoric horses and American camels and the first giant condors in Nevada.[15][16]

Natural history museums

- Las Vegas Natural History Museum, Las Vegas[17]

- Marjorie Barrick Museum of Natural History, Las Vegas[18]

- Nevada State Museum, Las Vegas,[19]

- Nevada State Museum, Carson City,[20]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Murray (1974); "Nevada", page 193.

- ↑ Murray (1974); "Nevada", pages 192-193.

- ↑ Nevada Facts and Emblems; "State Fossil".

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Noble, Scotchmoor, Springer (2005); "Paleontology and geology".

- ↑ Murray (1974); "Nevada", page 195.

- ↑ Weishampel, et al. (2004); "3.9 Nevada, United States", page 582.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Murray (1974); "Nevada", page 194.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Murray (1974); "Nevada", page 192.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Mayor (2005); "Paiute and Ute Fossil Knowledge in the Great Basin", page 151.

- ↑ Mayor (2005); "Red-Haired Cannibal Giants of Lovelock Cave, Nevada", page 342.

- ↑ Mayor (2005); "Red-Haired Cannibal Giants of Lovelock Cave, Nevada", page 343.

- ↑ Mayor (2005); "Paiute and Ute Fossil Knowledge in the Great Basin", page 152.

- ↑ Mayor (2005); "Apache Fossil Legends", pages 162-163.

- ↑ Murray (1974); "Nevada", pages 193-194.

- ↑ Margaret Lyneis (2007-07-17). "Tule Springs Archaeology and Paleontology". ONLINE NEVADA ENCYCLOPEDIA. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- ↑ "Tule Springs". Nevada State Historic Preservation Office. Retrieved 2010-06-30.

- ↑ Las Vegas Museum of Natural History; "Home".

- ↑ Barrick Museum; "Visit Us".

- ↑ Nevada State Museum, Las Vegas; "NSMLV".

- ↑ Nevada State Museum, Carson City; "NSMCC".

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paleontology in Nevada. |

- Home. Las Vegas Museum of Natural History. Accessed 12-31-12.

- Mayor, Adrienne. Fossil Legends of the First Americans. Princeton University Press. 2005. ISBN 0-691-11345-9.

- Murray, Marian. 1974. Hunting for Fossils: A Guide to Finding and Collecting Fossils in All 50 States. Collier Books. 348 pp.

- Nevada Facts and State Emblems. Nevada Legislature. Accessed 01-03-13.

- Noble, Paula, Judy Scotchmoor, Dale Springer. July 1, 2005. "Nevada, US." The Paleontology Portal. Accessed September 21, 2012.

- Visit Us. Marjorie Barrick Museum. Accessed 12-31-12.

- Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. 861 pp. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

External links

- Geologic units in Nevada

- Paleoportal: Nevada

- Late Triassic Ichthyosaur And Invertebrate Fossils In Nevada Includes: detailed text; on-site photographs; and images of fossils.

- A Visit To Ammonite Canyon, Nevada Includes: detailed text; on-site photographs; and images of fossils.