Palaestina Salutaris

| Palaestina III Salutaris εξοικονόμησης Παλαιστίνη | |||||

| Province of the Byzantine Empire, Diocese of the East | |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| Capital | Petra | ||||

| Historical era | Late Antiquity | ||||

| - | Established | c.390 | |||

| - | Persian occupation | 612–628 | |||

| - | Muslim conquest of Syria | 636 | |||

| Today part of | | ||||

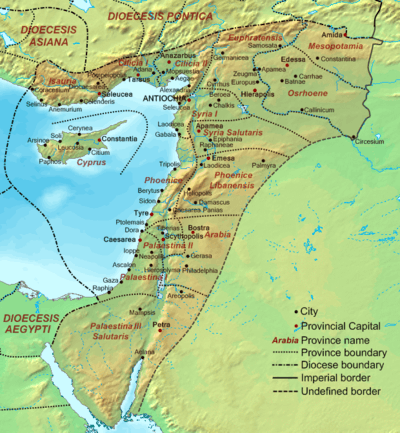

Palaestina Salutaris or Palaestina Tertia was a Byzantine (Eastern Roman) province, which covered the area of the Negev (or Edom), Sinai (except the north western coast) and south-west of Transjordan, south of the Dead Sea. The province, a part of the Diocese of the East, was split from Arabia Petraea in the 6th century and existed until the Muslim Arab conquests of the 7th century.

Background

In 105, the territories east of Damascus and south to the Red Sea were annexed from the Nabatean kingdom and reformed into the province of Arabia with a capital Petra and Bostra (north and south). The province was enlarged by Septimius Severus in 195, and is believed to have split into two provinces: Arabia Minor or Arabia Petraea and Arabia Major, both subject to imperial legates called consularis, each with a legion.

By the 3rd century, the Nabataeans had stopped writing in Aramaic and begun writing in Greek instead, and by the 4th century they had partially converted to Christianity, a process completed in the 5th century.[1]

Petra declined rapidly under late Roman rule, in large part from the revision of sea-based trade routes. In 363 an earthquake destroyed many buildings, and crippled the vital water management system.[2]

The area became organized under late Roman Empire as part of the Diocese of the East (314), in which it was included together with the provinces of Isauria, Cilicia, Cyprus (until 536), Euphratensis, Mesopotamia, Osroene, Phoenice and Arabia Petraea.

Byzantine rule in the 4th century introduced Christianity to the population.[3] Agricultural-based cities were established and the population grew exponentially.[3] Under Byzantium (since 390), a new subdivision did further split the province of Cilicia into Cilicia Prima, Cilicia Secunda; Syria Palaestina was split into Syria Prima, Syria Salutaris, Phoenice Lebanensis, Palaestina Prima, Palaestina Secunda and eventually also Palaestina Salutaris (in 6th century).

History

Palaestina Tertia included the Negev, southern Transjordan, once part of Arabia Petraea, and most of Sinai with Petra as the usual residence of the governor. Palestina Tertia was also known as Palaestina Salutaris.[4][5] According to historian H.H. Ben-Sasson,[6]

Trading relations existed between the cities of Palaestina Salutaris and the Arab tribes of the Hejaz (Arabia Major), particularly with the southern Tertian cities of Petra and Gaza. Muhammed, his father (Abd Allah) and his great-grandfather (Hashim, who died in Gaza) all traveled on trading routes through the region in the 6th century,[7] and in 583 Muhammed is said to have met with Nestorian monk Bahira at Bosra.

The Muslim Arab invaders found the remnants of the Nabataeans of Transjordan and Negev transformed into peasants. Their lands were divided between the new Qahtanite Arab tribal kingdoms of the Byzantine vassals the Ghassanid Arabs and the Himyarite vassals the Kindah Arab Kingdom in North Arabia, forming parts of the Bilad al-Sham province in early Chalifates.

Episcopal sees

Ancient episcopal sees of Palaestina Salutaris or Palaestina III (metropolitan see: Petra) listed in the Annuario Pontificio as titular sees:[8]

- Aela

- Arad

- Areopolis (Rabba)

- Arindela

- Augustopolis in Palaestina

- Bacatha in Palaestina

- Carac-Moba

- Elusa

- Iotapa in Palaestina

- Petra in Palaestina

- Pharan (Uâdi-Feiran)

See also

References

- ↑ Rimon, Ofra. "The Nabateans in the Negev". Hecht Museum. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- ↑ Glueck, Grace (2003-10-17). "ART REVIEW; Rose-Red City Carved From the Rock". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Mariam Shahin. Palestine: A Guide: P459 (2005) Interlink Books. ISBN 156656557

- ↑ Mariam Shahin. Palestine: A Guide: P8. (2005) Interlink Books. ISBN 156656557

- ↑ "Roman Arabia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ↑ H.H. Ben-Sasson, A History of the Jewish People, Harvard University Press, 1976, ISBN 0-674-39731-2, p. 351

- ↑ A History of Palestine, 634–1099, Moshe Gil, pp. 16–17

- ↑ Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), "Sedi titolari", pp. 819-1013

- From Provincia Arabia to Palaestina Tertia: The Impact of Geography, Economy, and Religion on Sedentary and Nomadic Communities in the Later Roman Province of Third Palestine, by Walter David Ward, 2008

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||