Pakistan

| Islamic Republic of Pakistan اسلامی جمہوریۂ پاكستان (Urdu) Islāmī Jumhūriyah-yi Pākistān |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: Īmān, Ittiḥād, Naẓm ایمان، اتحاد، نظم (Urdu) "Faith, Unity, Discipline" [1] |

||||||

| Anthem: Qaumī Tarānah قومی ترانہ |

||||||

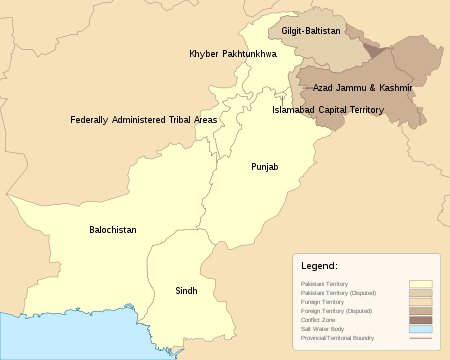

.svg.png) Area controlled by Pakistan shown in dark green; claimed but uncontrolled territory shown in light green.

|

||||||

| Capital | Islamabad 33°40′N 73°10′E / 33.667°N 73.167°E | |||||

| Largest city | ||||||

| Official languages | ||||||

| Regional languages | Punjabi, Pashto, Sindhi, Saraiki, Balochi, Kashmiri, Brahui, Hindko, Shina, Balti, Khowar, Burushaski Yidgha, Dameli, Kalasha, Gawar-Bati, Domaaki[4][5] | |||||

| Religion | Islam | |||||

| Demonym | Pakistani | |||||

| Government | Federal parliamentary republic | |||||

| - | President | Mamnoon Hussain (PML-N) | ||||

| - | Prime Minister | Nawaz Sharif (PML-N) | ||||

| - | Chief Justice | Nasir-ul-Mulk | ||||

| - | Chairman Senate | Raza Rabbani (PPP) | ||||

| - | Speaker National Assembly | Ayaz Sadiq (PML-N) | ||||

| Legislature | Majlis-e-Shoora | |||||

| - | Upper house | Senate | ||||

| - | Lower house | National Assembly | ||||

| Independence from the British Empire | ||||||

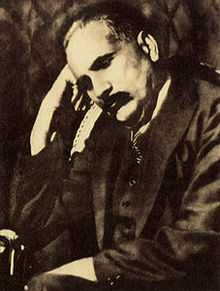

| - | Conception[6] | 29 December 1930 | ||||

| - | Declaration | 28 January 1933 | ||||

| - | Resolution | 23 March 1940 | ||||

| - | Dominion | 14 August 1947 | ||||

| - | Islamic Republic | 23 March 1956 | ||||

| - | Fall of Dhaka | 16 December 1971 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 803,940 km2[lower-alpha 1] (36th) 310,403 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | 3.1 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2014 estimate | 196,174,380 [8] (6th) | ||||

| - | Density | 234.4/km2 (55th) 607.4/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2015 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $928.433 billion[9] (26th) | ||||

| - | Per capita | $4,886[9] (136th) | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2015 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $249.477 billion[10] (42nd) | ||||

| - | Per capita | $1,313[10] (153rd) | ||||

| Gini (2008) | 30.0[11] medium |

|||||

| HDI (2013) | low · 146th |

|||||

| Currency | Pakistani rupee (₨) (PKR) | |||||

| Time zone | PKT (UTC+5) | |||||

| - | Summer (DST) | (UTC+6b) | ||||

| Drives on the | left[13] | |||||

| Calling code | +92 | |||||

| ISO 3166 code | PK | |||||

| Internet TLD | .pk | |||||

| a. | See also Pakistani English. | |||||

| b. | Not always observed; see Daylight saving time in Pakistan. | |||||

Pakistan (![]() i/ˈpækɨstæn/ or

i/ˈpækɨstæn/ or ![]() i/pɑːkiˈstɑːn/; Urdu: پاكستان ALA-LC: Pākistān, pronounced [pɑːkɪst̪ɑːn]), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan (Urdu: اسلامی جمہوریۂ پاكستان ALA-LC: Islāmī Jumhūriyah-yi Pākistān IPA: [ɪslɑːmiː d͡ʒʊmɦuːriəɪh pɑːkɪst̪ɑːn]), is a sovereign country in South Asia. With a population exceeding 180 million people, it is the sixth most populous country and with an area covering 796,095 km2 (307,374 sq mi), it is the 36th largest country in the world in terms of area. Pakistan has a 1,046-kilometre (650 mi) coastline along the Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Oman in the south and is bordered by the nations of India to the east, Afghanistan to the west, Iran to the southwest and China in the far northeast respectively. It is separated from Tajikistan by Afghanistan's narrow Wakhan Corridor in the north, and also shares a marine border with Oman.

i/pɑːkiˈstɑːn/; Urdu: پاكستان ALA-LC: Pākistān, pronounced [pɑːkɪst̪ɑːn]), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan (Urdu: اسلامی جمہوریۂ پاكستان ALA-LC: Islāmī Jumhūriyah-yi Pākistān IPA: [ɪslɑːmiː d͡ʒʊmɦuːriəɪh pɑːkɪst̪ɑːn]), is a sovereign country in South Asia. With a population exceeding 180 million people, it is the sixth most populous country and with an area covering 796,095 km2 (307,374 sq mi), it is the 36th largest country in the world in terms of area. Pakistan has a 1,046-kilometre (650 mi) coastline along the Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Oman in the south and is bordered by the nations of India to the east, Afghanistan to the west, Iran to the southwest and China in the far northeast respectively. It is separated from Tajikistan by Afghanistan's narrow Wakhan Corridor in the north, and also shares a marine border with Oman.

The territory that now constitutes Pakistan was previously home to several ancient cultures, including the Mehrgarh of the Neolithic and the Bronze Age Indus Valley Civilisation, and was later home to kingdoms ruled by people of different faiths and cultures, including Hindus, Indo-Greeks, Muslims, Turco-Mongols, Afghans and Sikhs. The area has been ruled by numerous empires and dynasties, including the Indian Mauryan Empire, the Persian Achaemenid Empire, Alexander of Macedonia, the Arab Umayyad Caliphate, the Mongol Empire, the Mughal Empire, the Durrani Empire, the Sikh Empire and the British Empire. As a result of the Pakistan Movement led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah and the subcontinent's struggle for independence, Pakistan was created in 1947 as an independent nation for Muslims from the regions in the east and west of Subcontinent where there was a Muslim majority. Initially a dominion, Pakistan adopted a new constitution in 1956, becoming an Islamic republic. A civil war in 1971 resulted in the secession of East Pakistan as the new country of Bangladesh.

Pakistan is a federal parliamentary republic consisting of four provinces and four federal territories. It is an ethnically and linguistically diverse country, with a similar variation in its geography and wildlife. A regional and middle power,[14][15] Pakistan has the seventh largest standing armed forces in the world and is also a nuclear power as well as a declared nuclear-weapons state, being the only nation in the Muslim world, and the second in South Asia, to have that status. It has a semi-industrialised economy with a well-integrated agriculture sector, its economy is the 26th largest in the world in terms of purchasing power and 45th largest in terms of nominal GDP and is also characterized among the emerging and growth-leading economies of the world.

The post-independence history of Pakistan has been characterised by periods of military rule, political instability and conflicts with neighbouring India. The country continues to face challenging problems, including overpopulation, terrorism, poverty, illiteracy, and corruption. Despite these factors it ranked 16th on the 2012 Happy Planet Index.[16] It is a member of the United Nations, the Commonwealth of Nations, the Next Eleven Economies, ECO, UfC, D8, Cairns Group, Kyoto Protocol, ICCPR, RCD, UNCHR, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, Group of Eleven, CPFTA, Group of 24, the G20 developing nations, ECOSOC, founding member of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, SAARC and CERN.[17]

Etymology

The name Pakistan literally means "Land of the Pure" in Urdu and Persian. It comes from the word Pāk meaning pure in Persian and Pashto[18] while the word istān is a Persian word meaning place of; it is a cognate of the Sanskrit word sthān'' (Devanagari: स्थान [st̪ʰaːn]).[19]

It was coined in 1933 as Pakstan by Choudhry Rahmat Ali, a Pakistan Movement activist, who published it in his pamphlet Now or Never,[20] using it as an acronym ("thirty million Muslim brethren who live in PAKSTAN") referring to the names of the five northern regions of the British Raj: Punjab, Afghania, Kashmir, Sindh, and Baluchistan".[21][22][23] The letter i was incorporated to ease pronunciation and form the linguistically correct and meaningful name.[24]

History

Early and medieval age

Some of the earliest ancient human civilisations in South Asia originated from areas encompassing present-day Pakistan.[25] The earliest known inhabitants in the region were Soanian during the Lower Paleolithic, of whom stone tools have been found in the Soan Valley of Punjab.[26] The Indus region, which covers most of Pakistan, was the site of several successive ancient cultures including the Neolithic Mehrgarh[27] and the Bronze Age Indus Valley Civilisation (2800–1800 BCE) at Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro.[28][29]

The Vedic Civilization (1500–500 BCE), characterised by Indo-Aryan culture, laid the foundations of Hinduism, which would become well established in the region.[30][31] Multan was an important Hindu pilgrimage centre.[32] The Vedic civilisation flourished in the ancient Gandhāran city of Takṣaśilā, now Taxila in Punjab.[27] Successive ancient empires and kingdoms ruled the region: the Persian Achaemenid Empire around 519 BCE, Alexander the Great's empire in 326 BCE[33] and the Maurya Empire founded by Chandragupta Maurya and extended by Ashoka the Great until 185 BCE.[27] The Indo-Greek Kingdom founded by Demetrius of Bactria (180–165 BCE) included Gandhara and Punjab and reached its greatest extent under Menander (165–150 BCE), prospering the Greco-Buddhist culture in the region.[27][34] Taxila had one of the earliest universities and centres of higher education in the world.[35][36][37][38]

The Medieval period (642–1219 CE) is defined by the spread of Islam in the region. During this period, Sufi missionaries played a pivotal role in converting a majority of the regional Buddhist and Hindu population to Islam.[39] The Rai Dynasty (489–632 CE) of Sindh, at its zenith, ruled this region and the surrounding territories.[40] The Pala Dynasty was the last Buddhist empire that under Dharampala and Devapala stretched across South Asia from what is now Bangladesh through Northern India to Pakistan and later to Kamboj region in Afghanistan.

The Arab conqueror Muhammad bin Qasim conquered Indus valley from Sindh to Multan in southern Punjab in 711 CE.[41][42][43][44] The Pakistan government's official chronology identifies this as the point where the "foundation" of Pakistan was laid.[41][45][46] This conquest set the stage for the rule of several successive Muslim empires in the region, including the Ghaznavid Empire (975–1187 CE), the Ghorid Kingdom and the Delhi Sultanate (1206–1526 CE). The Lodi dynasty, the last of the Delhi Sultanate, was replaced by the Mughal Empire (1526–1857 CE). The Mughals introduced Persian literature and high culture, establishing the roots of Indo-Persian culture in the region.[47] In the early 16th century, the region remained under the Mughal Empire ruled by Muslim emperors.[48] By the early 18th century, the increasing European influence caused to slowly disintegrate the empire with the lines between commercial and political dominance being increasingly blurred.[48]

During this time, the English East India Company, had established coastal outposts.[48] Control over the seas, greater resources, technology, and military force projection by East India Company of British Empire led it to increasingly flex its military muscle; a factor that was crucial in allowing the Company to gain control over subcontinent by 1765 and sidelining the European competitors.[49] Expanding access beyond Bengal and the subsequent increased strength and size of its army enabled it to annex or subdue most of region by the 1820s.[48] To many historians, this marked the starting of region's colonial period.[48] By this time, with its economic power severely curtailed by the British parliament and itself effectively made an arm of British administration, the Company began to more consciously enter non-economic arenas such as education, social reform, and culture.[48] Such reforms included the enforcement of English Education Act in 1835 and the introduction of the Indian Civil Service (ICS).[50] Tradition Madrasahs– a primary institutions of higher learning for Muslims in subcontinent– were no longer supported by the English Crown, and nearly all of the Madrasahs lost their financial endowment.[51]

Colonial period

The gradual decline of the Mughal Empire in the early 18th century enabled Sikh Empire's influence to control larger areas until the British East-India Company gained ascendancy over the Indian subcontinent.[52] The rebellion in 1857 (or Sepoy mutiny) was the region's major armed and serious struggle against the British Empire and Queen Victoria.[53] Divergence in the relationship between Hinduism and Islam created a major rift in British India; thus instigating racially-motivated religious violence in India.[54] The language controversy further escalated the tensions between Hindus and Muslims.[55] The Hindu renaissance witnessed the awakening of intellectualism in traditional Hinduism and saw the emergence of more assertive influence in social and political sphere in British India.[56][57] Intellectual movement to counter the Hindu renaissance was led by Sir Syed Ahmad Khan who help founded the All-India Muslim League in 1901 and envisioned as well as advocated for the Two-nation theory.[52] In contrast to Indian Congress's anti-British efforts, the Muslim League was a pro-British whose political program inherited the British values that would shape the Pakistan's future civil society.[58][59] In the events during the World War I, the British Intelligence foiled an anti-English conspiracy involving the nexus of Congress and the German Empire.[60] The largely non-violent independence struggle led by the Indian Congress engaged millions of protesters in mass campaigns of civil disobedience in the 1920s and 1930s against the British Empire.[61][62][63]

The Muslim League slowly rose to mass popularity in the 1930s amid fears of under-representation and neglect of Muslims in politics. In his presidential address of 29 December 1930, Allama Iqbal called for "the amalgamation of North-West Muslim-majority Indian states" consisting of Punjab, North-West Frontier Province, Sind and Baluchistan.[65] Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan, greatly espoused the two-nation theory and led the Muslim League to adopt the Lahore Resolution of 1940, popularly known as the Pakistan Resolution.[52] Events leading to the World War II, Jinnah and British educated founding fathers in the Muslim League supported the United Kingdom's war efforts, countering opposition against it whilst worked towards Sir Syed's vision.[66]

As cabinet mission failed in India, the Great Britain announced the intentions to end its raj in India in 1946–47.[67] Nationalists in British India– including Jawaharlal Nehru and Abul Kalam Azad of Congress, Jinnah of Muslim League, and Master Tara Singh representing the Sikhs—agreed to the proposed terms of transfer of power and independence in June 1947.[68] As the United Kingdom agreed upon partitioning of India in 1947, the modern state of Pakistan was established on 14 August 1947 (27th of Ramadan in 1366 of the Islamic Calendar) in amalgamating the Muslim-majority eastern and northwestern regions of British India.[63] It comprised the provinces of Balochistan, East Bengal, the North-West Frontier Province, West Punjab and Sindh; thus forming Pakistan.[52][68] The partitioning of Punjab and Bengal led to the series of violent communal riots across India and Pakistan; millions of Muslims moved to Pakistan and millions of Hindus and Sikhs moved to India.[69] Dispute over Jammu and Kashmir led to the First Kashmir War in 1948.[70][71]

Independence and modern Pakistan

After independence from the partition of India in 1947, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the President of Muslim League, became nation's first Governor-General as well as first President-Speaker of the Parliament.[72] Meanwhile, Pakistan's founding fathers agreed upon appointing Liaquat Ali Khan, the secretary-general of the party, nation's first Prime Minister. A dominion status in the Commonwealth of Nations, Pakistan was under two British monarch when George VI relinquished the title of Emperor of India to become King of Pakistan in 1947.[72] After George VI's death on 6 February 1952, Elizabeth II became the Queen of Pakistan who retained the title until Pakistan becoming the Islamic republic in 1956,[73] but democracy was stalled by the martial law enforced by President Iskander Mirza who was replaced by army chief, General Ayub Khan. Forming presidential system in 1962, the country experienced exceptional growth until a second war with India in 1965 which led to economic downfall and wide-scale public disapproval in 1967.[74][75] Consolidating the control from Ayub Khan in 1969, President Yahya Khan had to deal with a devastating cyclone which caused 500,000 deaths in East Pakistan.[76]

In 1970, Pakistan held its first democratic elections since independence, that were meant to mark a transition from military rule to democracy, but after the East Pakistani Awami League won against Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP); Yahya Khan and military establishment refused to hand over power.[77][78] Instigated civil unrest invited the military launched an operation on 25 March 1971, aiming to regain control of the province.[77][78] The genocide carried out during this operation led to a declaration of independence and to the waging of a war of liberation by the Bengali Mukti Bahini forces in East Pakistan, with support from India.[78][79] However, in West Pakistan the conflict was described as a civil war as opposed to War of Liberation.[80]

Independent estimates of civilian deaths during this period range from 300,000 to 3 million.[81] Preemptive strikes on India by the Pakistan's air force, navy, and marines sparked the conventional war in 1971, which witnessed the Indian victory and East Pakistan gaining independence as Bangladesh.[78]

With Pakistan surrendering in the war, Yahya Khan was replaced by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto as President; the country worked towards promulgating constitution and putting the country on roads of democracy. Democratic rule resumed from 1972 to 1977– an era of self-consciousness, intellectual leftism, nationalism, and nationwide reconstruction.[82] During this period, Pakistan embarked on ambitiously developing the nuclear deterrence in 1972 in a view to prevent any foreign invasion; the country's first nuclear power plant was inaugurated, also the same year.[83][84] Accelerated in response to first nuclear test by India in 1974, this crash program completed in 1979.[84] Democracy ended with a military coup in 1977 against the leftist PPP, which saw General Zia-ul-Haq becoming the president in 1978. From 1977–88, President Zia's corporatisation and economic Islamisation initiatives led to Pakistan becoming one of the fastest-growing economies in South Asia.[85] While consolidating the nuclear development, increasing Islamization,[86] and the rise homegrown conservative philosophy, Pakistan helped subsidize and distribute U.S. resources to factions of the mujahideen against the USSR's intervention in communist Afghanistan.[87][88]

President Zia died in a plane crash in 1988, and Benazir Bhutto, daughter of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, was elected as country's first female Prime Minister. The Pakistan Peoples Party followed by conservative Pakistan Muslim League (N), and over the next decade whose two leaders fought for power, alternating in office while the country's situation worsened; economic indicators fell sharply, in contrast to the 1980s. This period is marked by prolonged stagflation, instability, corruption, nationalism, geopolitical rivalry with India, and the clash of left wing-right wing ideologies.[89][90] As PML(N) securing supermajority in elections in 1997, Sharif authorised the nuclear testings (See:Chagai-I and Chagai-II), as a retaliation to second nuclear tests ordered by India, led by Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee in May 1998.[91]

Military tension between the two countries in the Kargil district led to the Kargil War of 1999, and a turbulence in civic-military relations allowed General Pervez Musharraf took over through a bloodless coup d'état.[92][93] Musharraf governed Pakistan as chief executive from 1999 to 2001 and as President from 2001 to 2008— a period of enlightenment, social liberalism, extensive economic reforms,[94] and direct involvement in the U.S.-led war on terrorism. When the National Assembly historically completed its first full five-year term on 15 November 2007, the new elections were called by Election Commission.[95] After the assassination of Benazir Bhutto in 2007, the PPP secured largest votes in the elections of 2008, appointing party member Yousaf Raza Gillani as Prime Minister.[96] Threatened to face impeachment, President Musharraf resigned on 18 August 2008, and was succeeded by Asif Ali Zardari.[97][98][99] Clashes with the judicature prompted Gillani's disqualification from the Parliament and as the Prime Minister in June 2012.[100] By its own financial calculations, Pakistan's involvement in the war on terrorism has cost up to ~$67.93 billion,[101][102] thousands of casualties and nearly 3 million displaced civilians.[103] The general election held in 2013 saw the PML(N) achieved almost supermajority, following which Nawaz Sharif became elected as the Prime Minister, returning to the post for the third time after fourteen years, in a democratic transition.[104]

Government and politics

Pakistan is a democratic parliamentary federal republic with Islam as the state religion.[105] The first set was adopted in 1956 but suspended by Ayub Khan in 1958 who replaced it with second set in 1962.[63] Complete and comprehensive Constitution was adopted in 1973—suspended by Zia-ul-Haq in 1977 but reinstated in 1985—is the country's most important document, laying the foundations of the current government.[106] The Pakistani military establishment has played an influential role in mainstream politics throughout Pakistan's political history.[63] Presidents are brought in by military coups who imposed in martial law in 1958–1971, 1977–1988, and 1999–2008.[107] As of current, Pakistan has a multi-party parliamentary system with clear division of powers and responsibilities between branches of government. The first successful demonstrative transaction was held in May 2013. Politics in Pakistan is centered and dominated by the homegrown conceive social philosophy, consisting the ideas of socialism, conservatism, and the third way. As of general elections held in 2013, the three main dominated political parties in the country: the centre-right conservative Pakistan Muslim League-N (PML-N); the centre-left socialist Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP); and the centrist and third-way Pakistan Movement for Justice (PTI) led by cricketer Imran Khan.

- Head of State: The President who is elected by an Electoral College is the ceremonial head of the state and is the civilian commander-in-chief of the Pakistan Armed Forces (with Chairman Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee as its principal military adviser), but military appointments and key confirmations in the armed forces are made by the Prime Minister after reviewing the reports on their merit and performances. Almost all appointed officers in the judicature, military, chairman joint chiefs and joint staff, and legislatures require the executive confirmation from the Prime Minister, whom the President must consult, by law. However, the powers to pardon and grant clemency vest with the President of Pakistan.

- Legislative: The bicameral legislature comprises a 100-member Senate (upper house) and a 342-member National Assembly (lower house). Members of the National Assembly are elected through the first-past-the-post system under universal adult suffrage, representing electoral districts known as National Assembly constituencies. According to the constitution, the 70 seats reserved for women and religious minorities are allocated to the political parties according to their proportional representation. Senate members are elected by provincial legislators, with all of provinces have equal representation.

- Executive: The Prime Minister is usually the leader of the majority rule party or a coalition in the National Assembly— the lower house. The Prime Minister serves as the head of government and is designated to exercise as the country's chief executive. The Prime Minister is responsible for appointing a cabinet consisting of ministers and advisors as well as running the government operations, taking and authorizing executive decisions, appointments and recommendations that require executive confirmation of the Prime Minister.

- Provincial governments: Each of the four province has a similar system of government, with a directly elected Provincial Assembly in which the leader of the largest party or coalition is elected Chief Minister. Chief Ministers oversees the provincial governments and head the provincial cabinet, it is common in Pakistan to have different ruling parties or coalitions in each provinces. The provincial assemblies have power to make laws and approve provincial budget which is commonly presented by the provincial finance minister every fiscal year. Provincial governors who play role as the ceremonial head of province are appointed by the President.[106]

- Judicature: The judiciary of Pakistan is a hierarchical system with two classes of courts: the superior (or higher) judiciary and the subordinate (or lower) judiciary. The Chief Justice of Pakistan is the chief judge who oversees the judicature's court system at all levels of command. The superior judiciary is composed of the Supreme Court of Pakistan, the Federal Shariat Court and five High Courts, with the Supreme Court at the apex. The Constitution of Pakistan entrusts the superior judiciary with the obligation to preserve, protect and defend the constitution. Neither the Supreme Court nor a High Court may exercise jurisdiction in relation to Tribal Areas, except otherwise provided for. The disputed regions of Azad Kashmir and Gilgit–Baltistan have separate court systems.

Foreign relations of Pakistan

.jpg)

A second most populous nation-state (after Indonesia) and being the singular nuclear power state in the Muslim world, enabled the country to play a important role in the international community.[108][109] With semi-agriculture and semi-industrialized economy, it foreign policy interacts with foreign nations and to determine its standard of interactions for its organizations, corporations and individual citizens.[110][111] Its clear geostrategic intentions were explained by Jinnah who described the principles and objectives of Pakistan's foreign policy in a broadcast message:[112] The objectives of foreign policy of Pakistan:

| “ | The foundation of our foreign policy is friendship with all nations across the globe. | ” |

| —Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Founder of Pakistan, 1947, source[112] | ||

Since then, Pakistan have tried maintaining balance relations with the foreign nations as part of its determined policy.[113][114][115] A non-signatory party of the Treaty on the Nuclear Non-Proliferation, Pakistan is a good and influential member of the IAEA.[116] In recent event, Pakistan has successfully blocked international initiatives to limit fissile material, as justifying that "treaty would target Pakistan specifically."[117] In most of its 20th century history, Pakistan's nuclear deterrence program focused on countering India's nuclear ambitions in the region, and nuclear tests by India eventually led Pakistan to reciprocate the event to maintain geopolitical balance as becoming nuclear power.[118] As of current, Pakistan now maintains a policy of credible minimum deterrence, terming its program as vital nuclear deterrence against any foreign aggression.[119][120]

Located in strategic and geopolitical corridor of the world's major maritime oil supply lines, communication fiber optics, Pakistan has proximity to the natural resources of Central Asian countries.[121] Pakistan is an influential and founding member of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) and is a major non-NATO ally of the United States in the war against terrorism— a status achieved in 2004.[122] Pakistan's foreign policy and geostrategy mainly focuses on economy and security against threats to its national identity and territorial integrity, and on the cultivation of close relations with Muslim countries.[123] Briefing on country's foreign policy in 2004, the Pakistani senator reportedly explains: "Pakistan highlights sovereign equality of states, bilateralism, mutuality of interests, and non-interference in each other's domestic affairs as the cardinal features of its foreign policy."[124] Pakistan is an active member of the United Nations and has a Permanent Representative to represent Pakistan's policy in international politics.[125] Recently, Pakistan has previously lobbied for the concept of "Enlightened Moderation" in the Muslim world.[126][127] Pakistan is also a member of Commonwealth of Nations,[128] the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), the Economic Cooperation Organisation (ECO)[129][130] and the G20 developing nations.[131] Pakistan does not have diplomatic relations with Israel;[132] nonetheless some Israeli citizens have visited the country on a tourist visas.[133] Based on mutual cooperation, the security exchange have taken place between two countries using Turkey as a communication conduit.[134] Despite Pakistan being the only country in the world that has not established a diplomatic relations with Armenia, the Armenian community still resides in Pakistan.[135]

Maintaining cultural, political, social, and economic relations with the Arab world and other countries in Muslim World is vital factor in Pakistan's foreign policy.[137] Pakistan was the first country to have established diplomatic relations with China and relations continues to be warm since China's war with India in 1962.[138] In the 1960s–1980s, Pakistan greatly helped China in reaching out to the world's major countries and helped facilitate U.S. President Nixon's state visit to China.[138] Despite the change of governments in Pakistan, variations in the regional and global situation, China policy in Pakistan continues to be dominant factor at all time.[138] In return, China is Pakistan's largest trading partner and economic cooperation have reached high points, with substantial Chinese investment in Pakistan's infrastructural expansion including the Pakistani deep-water port at Gwadar.[139][140][141] Both countries have signed the Free Trade Agreement in 2000s, and Pakistan continues to serve as China's communication bridge in the Muslim World.[142]

Difficulties in relations and geopolitical rivalry with India, Pakistan maintains close cultural and political relations with Turkey and Iran.[143] Pakistan has a second largest Shia Islam follower, after Iran, and has maintains close cultural, political, economic, and military relations with Iran.[144] Iran was the first country to establish relations with Pakistan, and since then, Iran has occupied influential place in Pakistan's foreign policy.[144] Turkey and Saudi Arabia also maintains respected position in Pakistan's foreign policy, and both countries has been a focal point in Pakistan's foreign policy.[143] The Kashmir conflict remains the major point of rift; three of their four wars were over this territory.[145] Due to ideological differences, Pakistan opposed the Soviet Union in 1950s and during Soviet-Afghan War in the 1980s, Pakistan was one of the closest allies of the United States.[124][146] Relations with Russia has greatly improved since 1999 and cooperation with various sectors have increased between Russia and Pakistan.[147] Pakistan has had "on-and-off" relations with the United States. A close ally of the United States in the Cold war, Pakistan's relation with the United States relations soured in the 1990s when the U.S. imposed sanctions because of Pakistan's secretive nuclear development.[148]

The United States-led war on terrorism led initially to an improvement in the relationship, but it was strained by a divergence of interests and resulting mistrust during the war in Afghanistan and by issues related to terrorism.[149][150][151][152] Since 1948, there has been an ongoing, and at times fluctuating, violent conflict in the southwestern province of Balochistan between various Baloch separatist groups, who seek greater political autonomy, and the central government of Pakistan.[153]

Administrative divisions

| Administrative Division | Capital | Population | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Balochistan | Quetta | 7,914,000 | |

| Punjab | Lahore | 101,000,000 | |

| Sindh | Karachi | 42,400,000 | |

| Khyber Pakhtunkhwa | Peshawar | 28,000,000 | |

| Gilgit–Baltistan | Gilgit | 1,800,000 | |

| FATA | 3,176,331 | ||

| Azad Kashmir | Muzaffarabad | 4,567,982 | |

| Islamabad Capital Territory | Islamabad | 1,151,868 |

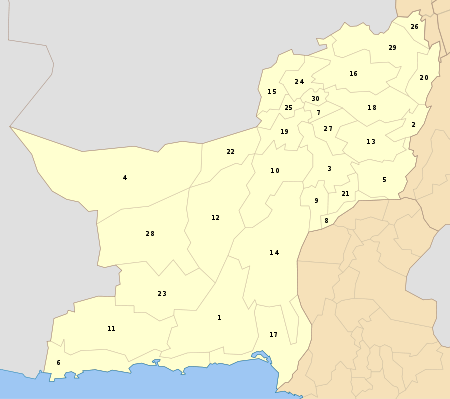

A federal parliamentary republic state, Pakistan is a federation that comprises four provinces: Punjab, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, Sindh, and Balochistan.[154] and four territories: the Tribal belt, Gilgit–Baltistan, Islamabad Capital Territory, and Kashmir. The Government of Pakistan exercises the de facto jurisdiction over the Frontier Regions and the western parts of the Kashmir Regions, which are organised into the separate political entities Azad Kashmir and Gilgit–Baltistan (formerly Northern Areas). In 2009, the constitutional assignment (the Gilgit–Baltistan Empowerment and Self-Governance Order) awarded the Gilgit–Baltistan a semi-provincial status, giving it self-government.[155]

The local government system consists of a three-tier system of districts, tehsils and union councils, with an elected body at each tier.[156] There are about 130 districts altogether, of which Azad Kashmir has ten[157] and Gilgit–Baltistan seven.[158] The Tribal Areas comprise seven tribal agencies and six small frontier regions detached from neighbouring districts.[159]

The law enforcement is carried out by a joint network of intelligence community with jurisdiction limited to the relevant province or territory. The National Intelligence Directorate coordinates the information intelligence at both federal and provincial level; including the FIA, IB, Motorway Police, and paramilitary forces such as the Pakistan Rangers and the Frontier Corps.[160]

The court system is organised as a hierarchy, with the Supreme Court at the apex, below which are High Courts, Federal Shariat Courts (one in each province and one in the federal capital), District Courts (one in each district), Judicial Magistrate Courts (in every town and city), Executive Magistrate Courts and civil courts. The Penal code has limited jurisdiction in the Tribal Areas, where law is largely derived from tribal customs.[160][161]

Military

The armed forces of Pakistan are the eighth largest in the world in terms of numbers in full-time service, with about 617,000 personnel on active duty and 513,000 reservists, as of tentative estimates in 2010.[162] They came into existence after independence in 1947, and the military establishment has frequently influenced in the national politics ever since.[107] Chain of command of the military is kept under the control of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee; all of the branches joint works, coordination, military logistics, and joint missions are under the Joint Staff HQ.[163] The Joint Staff HQ is composed of the Air HQ, Navy HQ, and Army GHQ in the vicinity of the Rawalpindi Military District.[164]

The Chairman Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee is the highest principle staff officer in the armed forces, and the chief military adviser to the civilian government though the chairman has no authority over the three branches of armed forces.[163] The Chairman joint chiefs controls the military from the JS HQ and maintains strategic communications between the military and the civilian government.[163] As of current, the Chairman joint chiefs is General Rashid Mahmood alongside with chief of army staff General Raheel Sharif,[165] chief of naval staff Admiral Muhammad Zaka,[166] and chief of air staff Air Chief Marshal Suhail Aman.[167] The main branches are the Army–Air Force–Navy–Marines, which are supported by the number of paramilitary forces in the country.[168] Control over the strategic arsenals, deployment, employment, development, military computers and command and control is a responsibility vested under the National Command Authority which oversaw the work on the nuclear policy as part of the credible minimum deterrence.[91]

The United States, Turkey, and China maintain close military relations and regularly export military equipment and technology transfer to Pakistan.[169] Joint logistics and major war games are occasionally carried out by the militaries of China and Turkey.[168][170][171] Philosophical basis for the military draft is introduced by the Constitution in times of emergency, but it has never been imposed.[172] Since 1947, Pakistan has been involved in four conventional wars, the first war occurred in Kashmir with Pakistan gaining control of Western Kashmir, (Azad Kashmir and Gilgit–Baltistan), and India capturing Eastern Kashmir (Jammu and Kashmir). Territorial problems eventually led to another conventional war in 1965; over the issue of Bengali refugees that led to another war in 1971 which resulted in Pakistan's unconditional surrender of East Pakistan.[173] Tensions in Kargil brought the two countries at the brink of war.[92] Since 1947, the unresolved territorial problems with Afghanistan saw border skirmishes which was kept mostly at the mountainous border. In 1961, the military and intelligence community repelled the Afghan incursion in the Bajaur Agency near the Durand Line border.[174][175] Rising tensions with neighboring USSR in their involvement in Afghanistan, Pakistani intelligence community, mostly the ISI, systematically coordinated the U.S. resources to the Afghan mujahideen and foreign fighters against the Soviet Union's presence in the region. Military reports indicated that the PAF was in engagement with the Soviet Air Force, supported by the Afghan Air Force during the course of the conflict;[176] one of which belonged to Alexander Rutskoy.[176]

Apart from its own conflicts, Pakistan has been an active participant in United Nations peacekeeping missions. It played a major role in rescuing trapped American soldiers from Mogadishu, Somalia, in 1993 in Operation Gothic Serpent.[177][178][179] According to UN reports, the Pakistani military are the largest troop contributors to UN peacekeeping missions.[180]

Pakistan has deployed its military in some Arab countries, providing defence, training, and playing advisory roles.[181][182] The PAF and Navy's fighter pilots have voluntarily served in Arab nations military against Israel in Six-Day War (1967) and the Yom Kippur War (1973), of which, the Pakistan's fighter pilots shot down ten Israeli planes in the Six-Day War.[177] Requested by the Saudi monarchy in 1979, the special forces units, operatives, and commandos were rushed to assist Saudi forces in Mecca to lead the operation of the Grand Mosque.[183] In 1991 Pakistan got involved with the Gulf War and sent 5,000 troops as part of a US-led coalition, specifically for the defence of Saudi Arabia.[184]

Since 2004, the military has been engaged in a war in North-West Pakistan, mainly against the homegrown Taliban factions.[185][186] Major operations undertaken by the Army include Operation Black Thunderstorm and Operation Rah-e-Nijat.[187][188]

Kashmir conflict

The Kashmir– the most northwesterly region of South Asia– is a primary territorial dispute that hindered the relations between India and Pakistan. Two nations have fought at least three large-scale conventional wars in successive years of 1947, 1965, and 1971. The conflict in 1971 witnessed Pakistan's unconditional surrender and a treaty that subsequently led to the independence of Bangladesh.[189] Other serious military engagements and skirmishes included the armed contacts in Siachen Glacier (1984) and Kargil (1999).[145] Approximately 45.1% of the Kashmir region is controlled by India while claiming the entire state of Jammu and Kashmir, including most of Jammu, the Kashmir Valley, Ladakh, and the Siachen.[145] The claim is contested by Pakistan, which approximately controls the 38.2% of the Kashmir region, known as the Azad Kashmir and Gilgit–Baltistan.[145][190]

The Kashmir conflict has its roots with the English Crown's decision of partitioning the British India in 1947. As part of the partition process, two nations had agreed that the rulers of princely states would be allowed to opt for either annexing with Pakistan or India, or in special cases to remain independent.[191] India claims the Kashmir on the basis of the Instrument of Accession— a legal agreement with Kashmir's leaders executed by Maharaja Hari Singh who agreed to accede the area to India.[192][193] Pakistan claims Kashmir on the basis of a Muslim majority and of geography, the same principles that were applied for the creation of the two independent states.[194][195] India referred the dispute to the United Nations on 1 January 1948.[196] A resolution passed in 1948, the UN's General Assembly asked Pakistan to remove most of its troops as a plebiscite would then be held. However, Pakistan failed to vacate the region and a ceasefire was reached in 1949 with the Line of Control (LoC) was established, dividing Kashmir between the two nations.[191]

Pakistan claims that its position is for the right of the people of Jammu and Kashmir to determine their future through impartial elections as mandated by the United Nations,[197] while India has stated that Kashmir is an integral part of India, referring to the Simla Agreement(1972) and to the fact that elections take place regularly.[198] In recent developments, certain Kashmiri independence groups believe that Kashmir should be independent of both India and Pakistan.[145]

Law enforcement

The law enforcement in Pakistan is carried out by joint network of several federal and provincial police agencies. The four provinces and the Islamabad Capital Territory each have a civilian police force with jurisdiction extending only to the relevant province or territory.[106] At the federal level, there are a number of civilian intelligence agencies with nationwide jurisdictions including the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA), Intelligence Bureau (IB), and the Motoway Patrol, as well as several paramilitary forces such as the National Guards (Northern Areas), the Rangers (Punjab and Sindh), and the Frontier Corps (Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan).

The most senior officers of all the civilian police forces also form part of the Police Service, which is a component of the civil service of Pakistan. Namely, there are four provincial police service including the Punjab Police, Sindh Police, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa Police, and the Balochistan Police; all headed by the appointed senior Inspector-Generals. The Islamabad has its own police component, the Capital Police, to maintain law and order in the capital. The CID bureaus are the crime investigation unit and forms a vital part in each provincial police service.

The law enforcement in Pakistan also has a Motorway Patrol which is responsible for enforcement of traffic and safety laws, security and recovery on Pakistan's inter-provincial motorway network. In each of provincial Police Service, it also maintains a respective Elite Police units led by the NACTA– a counter-terrorism police unit as well as providing VIP escorts. In Punjab and Sindh, the Pakistan Rangers are an internal security force with the prime objective to provide and maintain security in war zones and areas of conflict as well as maintaining law and order which includes providing assistance to the police.[199] The Frontier Corps serves the similar purpose in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, and the Balochistan.[199]

Geography, environment and climate

The geography and climate of Pakistan are extremely diverse, and the country is home to a wide variety of wildlife.[200] Pakistan covers an area of 796,095 km2 (307,374 sq mi), approximately equal to the combined land areas of France and the United Kingdom. It is the 36th largest nation by total area, although this ranking varies depending on how the disputed territory of Kashmir is counted. Pakistan has a 1,046 km (650 mi) coastline along the Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Oman in the south[201] and land borders of 6,774 km (4,209 mi) in total: 2,430 km (1,510 mi) with Afghanistan, 523 km (325 mi) with China, 2,912 km (1,809 mi) with India and 909 km (565 mi) with Iran.[106] It shares a marine border with Oman,[202] and is separated from Tajikistan by the cold, narrow Wakhan Corridor.[203] Pakistan occupies a geopolitically important location at the crossroads of South Asia, the Middle East and Central Asia.[204]

Geologically, Pakistan overlaps the Indian tectonic plate in its Sindh and Punjab provinces; Balochistan and most of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa are within the Eurasian plate, mainly on the Iranian plateau. Gilgit–Baltistan and Azad Kashmir lie along the edge of the Indian plate and hence are prone to violent earthquakes. Ranging from the coastal areas of the south to the glaciated mountains of the north, Pakistan's landscapes vary from plains to deserts, forests, hills and plateaus .[205]

Pakistan is divided into three major geographic areas: the northern highlands, the Indus River plain and the Balochistan Plateau.[206] The northern highlands contain the Karakoram, Hindu Kush and Pamir mountain ranges (see mountains of Pakistan), which contain some of the world's highest peaks, including five of the fourteen eight-thousanders (mountain peaks over 8,000 metres or 26,250 feet), which attract adventurers and mountaineers from all over the world, notably K2 (8,611 m or 28,251 ft) and Nanga Parbat (8,126 m or 26,660 ft).[207] The Balochistan Plateau lies in the west and the Thar Desert in the east. The 1,609 km (1,000 mi) Indus River and its tributaries flow through the country from the Kashmir region to the Arabian Sea. There is an expanse of alluvial plains along it in Punjab and Sindh.[208]

The climate varies from tropical to temperate, with arid conditions in the coastal south. There is a monsoon season with frequent flooding due to heavy rainfall, and a dry season with significantly less rainfall or none at all. There are four distinct seasons: a cool, dry winter from December through February; a hot, dry spring from March through May; the summer rainy season, or southwest monsoon period, from June through September; and the retreating monsoon period of October and November.[52] Rainfall varies greatly from year to year, and patterns of alternate flooding and drought are common.[209]

-

Shimshal in Northern Pakistan

-

Thar Desert forms a natural boundary between India and Pakistan

-

The Clifton Beach in Karachi

-

View from Skardu Fort towards Indus River

Flora and fauna

The diversity of landscapes and climates in Pakistan allows a wide variety of trees and plants to flourish. The forests range from coniferous alpine and subalpine trees such as spruce, pine and deodar cedar in the extreme northern mountains, through deciduous trees in most of the country (for example the mulberry-like shisham found in the Sulaiman Mountains), to palms such as coconut and date in southern Punjab, southern Balochistan and all of Sindh. The western hills are home to juniper, tamarisk, coarse grasses and scrub plants. Mangrove forests form much of the coastal wetlands along the coast in the south.[210]

Coniferous forests are found at altitudes ranging from 1,000 to 4,000 metres in most of the northern and northwestern highlands. In the xeric regions of Balochistan, date palm and Ephedra are common. In most of Punjab and Sindh, the Indus plains support tropical and subtropical dry and moist broadleaf forestry as well as tropical and xeric shrublands. These forests are mostly of mulberry, acacia, and eucalyptus.[211] About 2.2% or 1,687,000 hectares (16,870 km2) of Pakistan was forested in 2010.[212]

The fauna of Pakistan reflects its varied climates too. Around 668 bird species are found there:[213][214] crows, sparrows, mynas, hawks, falcons and eagles commonly occur. Palas, Kohistan, has a significant population of Western Tragopan.[215] Many birds sighted in Pakistan are migratory, coming from Europe, Central Asia and India.[216]

The southern plains are home to mongooses, civets, hares, the Asiatic jackal, the Indian pangolin, the jungle cat and the desert cat. There are mugger crocodiles in the Indus, and wild boar, deer, porcupines and small rodents are common in the surrounding areas. The sandy scrublands of central Pakistan are home to Asiatic jackals, striped hyenas, wildcats and leopards.[217][218] The lack of vegetative cover, the severe climate and the impact of grazing on the deserts have left wild animals in a precarious position. The chinkara is the only animal that can still be found in significant numbers in Cholistan. A small number of nilgai are found along the Pakistan-India border and in some parts of Cholistan.[217][219] A wide variety of animals live in the mountainous north, including the Marco Polo sheep, the urial (a subspecies of wild sheep), Markhor and Ibex goats, the Asian black bear and the Himalayan brown bear.[217][220][221] Among the rare animals found in the area are the snow leopard,[220] the Asiatic cheetah[222] and the blind Indus river dolphin, of which there are believed to be about 1,100 remaining, protected at the Indus River Dolphin Reserve in Sindh.[220][223] In total, 174 mammals, 177 reptiles, 22 amphibians, 198 freshwater fish species and 5,000 species of invertebrates (including insects) have been recorded in Pakistan.[213][214]

The flora and fauna of Pakistan suffer from a number of problems. Pakistan has the second-highest rate of deforestation in the world. This, along with hunting and pollution, is causing adverse effects on the ecosystem. The government has established a large number of protected areas, wildlife sanctuaries, and game reserves to deal with these issues.[213][214]

National parks and Wildlife sanctuaries

As of present, there are around 157 protected areas in Pakistan that are recognized by IUCN. According to the 'Modern Protected Areas' legislation, a national park is a protected area set aside by the government for the protection and conservation of its outstanding scenery and wildlife in a natural state. The oldest national park is Lal Suhanra in Bahawalpur District, established in 1972.[224] It is also the only biosphere reserve of Pakistan. Lal Suhanra is the only national park established before the independence of the nation in August 1947. Central Karakoram in Gilgit Baltistan is currently the largest national park in the country, spanning over a total approximate area of 1,390,100 hectares (3,435,011.9 acres). The smallest national park is the Ayub, covering a total approximate area of 931 hectares (2,300.6 acres).

Infrastructure

Economy

Pakistan is a rapidly developing country[225][226][227] and is one of the Next Eleven, the eleven countries that, along with the BRICs, have a high potential to become the world's largest economies in the 21st century.[228] However, after decades of social instability, as of 2013, serious deficiencies in macromangament and unbalanced macroeconomics in basic services such as train transportation and electrical energy generation had developed.[229] The economy is semi-industrialized, with centres of growth along the Indus River.[230][231][232] The diversified economies of Karachi and Punjab's urban centres coexist with less developed areas in other parts of the country.[231] Pakistan's estimated nominal GDP as of 2011 is US$202 billion. The GDP by PPP is US$838,164 million.[233] The estimated nominal per capita GDP is US$1,197, GDP (PPP)/capita is US$4,602 (international dollars), and debt-to-GDP ratio is 55.5%.[234][235] According to the World Bank, Pakistan has important strategic endowments and development potential. The increasing proportion of Pakistan’s youth provides the country with a potential demographic dividend and a challenge to provide adequate services and employment.[236]

Pakistan would become the 18th largest economy in the world by 2050 with a GDP of US$ 3.33 trillion.

A 2013 report published by the World Bank positioned Pakistan's economy at 24th largest in the world by purchasing power and 45th largest in absolute dollars.[232] It is South Asia's second largest economy, representing about 15.0% of regional GDP.[238][239] Pakistan's economic growth since its inception has been varied. It has been slow during periods of democratic transition, but excellent during the three periods of martial law, although the foundation for sustainable and equitable growth was not formed.[75] The early to middle 2000s was a period of rapid economic reforms; the government raised development spending, which reduced poverty levels by 10% and increased GDP by 3%.[106][240] The economy cooled again from 2007.[106] Inflation reached 25.0% in 2008[241] and Pakistan had to depend on a fiscal policy backed by the International Monetary Fund to avoid possible bankruptcy.[242][243] A year later, the Asian Development Bank reported that Pakistan's economic crisis was easing.[244] The inflation rate for the fiscal year 2010–11 was 14.1%.[245] On January 2014, a survey conducted by the Japan External Trade Organization placed Pakistan just behind Taiwan in terms of business generated by Japanese companies. Pakistan's data was generated from 27 Japanese firms doing business here. The results found that 74.1% of the Japanese companies estimated operating profit in 2013.[246]

Pakistan is one of the largest producers of natural commodities, and its labour market is the 10th largest in the world. The 7 million strong Pakistani diaspora, contributed US$11.2 billion to the economy in 2011-12.[249] The major source countries of remittances to Pakistan includes in the UAE, United States, Saudi Arabia, Gulf states (Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, and Oman), Australia, Canada, Japan, Untied Kingdom, Norway, and Switzerland .[250][251] According to the World Trade Organization, Pakistan's share of overall world exports is declining; it contributed only 0.128% in 2007.[252] The trade deficit in the fiscal year 2010–11 was US$11.217 billion.[253]

The structure of the Pakistani economy has changed from a mainly agricultural to a strong service base. Agriculture as of 2010 accounts for only 21.2% of the GDP. Even so, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, Pakistan produced 21,591,400 metric tons of wheat in 2005, more than all of Africa (20,304,585 metric tons) and nearly as much as all of South America (24,557,784 metric tons).[254] Between 2002 and 2007 there was substantial foreign investment in Pakistan's banking and energy sectors.[255] Other important industries include clothing and textiles (accounting for nearly 60% of exports), food processing, chemicals manufacture, iron and steel.[256] There is great potential for tourism in Pakistan, but it is severely affected by the country's instability.[257] Pakistan's cement is also fast growing mainly because of demand from Afghanistan and countries boosting real estate sector, In 2013 Pakistan exported 7,708,557 metric tons of cement.[258] Pakistan has an installed capacity of 44,768,250 metric tons of cement and 42,636,428 metric tons of clinker. In the 2012–2013 cement industry in Pakistan became the most profitable sector of economy.[259]

The Foreign direct investment (FDI) in Pakistan soared by 180.6% year-on-year to US$2.22 billion and portfolio investment by 276.1% to US$407.4 million during the first nine months of fiscal year 2006, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) reported on 24 April. During July–March 2005–06, the FDI year-on-year increased to US$2.224 billion from only US$792.6 million and portfolio investment to US$407.4 million, whereas it was US$108.1 million in the corresponding period last year, according to the latest statistics released by the State Bank.[260] Pakistan has achieved FDI of almost US$8.4 billion in the financial year 2006-07, surpassing the government target of $4 billion.[261] Foreign investment had significantly declined by 2010, dropping by 54.6% due to Pakistan's political instability and weak law and order, according to the State Bank.[262]

The textile industry enjoys a pivotal position in the exports of Pakistan. Pakistan is the 8th largest exporter of textile products in Asia. This sector contributes 9.5% to the GDP and provides employment to about 15 million people or roughly 30% of the 49 million workforce of the country. Pakistan is the 4th largest producer of cotton with the third largest spinning capacity in Asia after China and India, and contributes 5% to the global spinning capacity. China is the second largest buyer of Pakistani textiles, importing US$1.527 billion of textiles last fiscal. Unlike U.S. where mostly value added textiles are imported, China buys only cotton yarn and cotton fabric from Pakistan. In 2012, Pakistani textile products accounted for 3.3% or US$1.07bn of total United Kingdom's textile imports, 12.4% or US$4.61bn of total Chinese textile imports, 2.98% or $2.98b of total United States' textile imports, 1.6% or US$0.88bn of total German textile imports and 0.7% or US$0.888bn of total Indian textile imports.[263]

The Pakistan's competitive yet profitable banking industry is continuously improving with a diversified pattern of ownership due to an active participation of foreign and local stakeholders. It has resulted into an increased competition among banks to attract a greater number of customers by the provision of quality services for long-term benefits. Now there are 6 full-fledged Islamic banks and 13 conventional banks offering products and services. Islamic banking and finance in Pakistan has experienced phenomenal growth. Islamic deposits – held by full-fledged Islamic banks and Islamic windows of conventional banks at present stand at 9.7% of total bank deposits in the country.[264] The list includes the largest Pakistani companies by revenue in 2012:

| Pakistan key economic statistics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Pakistan GDP composition by sector | [265] | |

| Agriculture | 25.3% | |

| Industry | 21.6% | |

| Services | 53.1% | |

| Labor force by occupation | [266] | |

| Agriculture | 45.1% | |

| Industry | 20.7% | |

| Services | 34.2% | |

| Employment | [267] | |

| Labour force | 59.7 million | |

| People employed | 56.0 million | |

| Natural Resources | [268][269] | |

| Copper | 12.3 million tonnes | |

| Gold | 20.9 million ounces | |

| Coal | 175 billion tonnes | |

| Shale Gas | 105 trillion cubic feet | |

| Shale Oil | 9 billion barrels | |

| Gas production | 4.2 billion cubic feet/day | |

| Oil production | 70,000 barrels/day | |

| Iron ore | 500 million[270] | |

| Corporations | Headquarters | 2012 revenue (Mil. $)[271] | Services |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pakistan State Oil | Karachi | 11,570 | Petroleum and Gas |

| Pak-Arab Refinery | Qasba Gujrat | 3,000 | Oil and refineries |

| Sui Northern Gas Pipelines | Lahore | 2,520 | Natural gas |

| Shell Pakistan | Karachi | 2,380 | Petroleum |

| Oil and Gas Development Co. | Islamabad | 2,230 | Petroleum and Gas |

| National Refinery | Karachi | 1,970 | Oil refinery |

| Hub Power Co. | Hub, Balochistan | 1,970 | Energy |

| K-Electric | Karachi | 1,840 | Energy |

| Attock Refinery | Rawalpindi | 1,740 | Oil refinery |

| Attock Petroleum | Rawalpindi | 1,740 | Petroleum |

| Lahore Electric Supply Co. | Lahore | 1,490 | Energy |

| Pakistan Refinery | Karachi | 1,440 | Petroleum and Gas |

| Sui Southern Gas Pipelines | Karachi | 1,380 | Natural gas |

| Pakistan International Airlines | Karachi | 1,360 | Aviation |

| Engro Corporation | Karachi | 1,290 | Food and Wholesale |

Nuclear power

Energy from the nuclear power source is provided by three licensed-commercial nuclear power plants, as of 2012 data.[272] Pakistan is the first Muslim country in the world to construct and operate civil nuclear power plants.[273] The Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC), the scientific and nuclear governmental authority, is solely responsible for operating these power plants, while the Pakistan Nuclear Regulatory Authority regulates safe usage of the nuclear energy.[274] The electricity generated by commercial nuclear power plants constitutes roughly ~5.8% of electricity generated in Pakistan, compared to ~62% from fossil fuel (petroleum), ~29.9% from hydroelectric power and ~0.3% from coal.[275][276][277] Pakistan is one of the four nuclear armed states (along with India, Israel, and North Korea) that is not a party to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty but is a member in good standing of the International Atomic Energy Agency.[278][279][280]

For the commercial usage of the nuclear power, China has provided an avid support for commercializing the nuclear power sources in Pakistan from early on, first providing the Chashma-I reactor. The Karachi-I, a Candu-type, was provided by Canada in 1971– the country's first commercial nuclear power plant. In subsequent years, People's Republic of China sold the nuclear power plant for energy and industrial growth of the country. In 2005, both countries reached out towards working on joint energy security plan, calling for a huge increase in generating capacity to more than 160,000 MWe by 2030. Original admissions by Pakistan, the government plans for lifting nuclear capacity to 8800 MWe, 900 MWe of it by 2015 and a further 1500 MWe by 2020.[281]

In June 2008, the nuclear commercial complex was expanded with the ground work of installing and operationalizing the Chashma-III and Chashma–IV nuclear power plants at Chashma, Punjab Province, each with 320–340 MWe and costing ₨. 129 billion,; from which the ₨. 80 billion of this from international sources, principally China.

A further agreement for China's help with the project was signed in October 2008, and given prominence as a counter to the U.S.–India agreement shortly preceding it. Cost quoted then was US$1.7 billion, with a foreign loan component of $1.07 billion. In 2013, the second nuclear commercial complex in Karachi was marginalized and expanded to additional reactors, based on the Chashma complex.[282]

The electrical energy is generated by various energy corporations and evenly distributed by the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (NEPRA) among the four provinces. However, the Karachi-based K-Electric and the Water and Power Development Authority (WAPDA) generates much of the electrical energy as well as gathering revenue nationwide.[283] Capacity to generate ~22,797MWt electricity has been installed in 2014, with the initiation of several energy projects in 2014.[275] Energy from the nuclear sources is provided by three licensed commercial nuclear power plants operated Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC) under licensed by the Nuclear Regulatory Authority.[284] Pakistan is the first Muslim country in the world to embark on a nuclear power program.[285] Commercial nuclear power plants generate roughly 5.8% of Pakistan's electricity, compared with about 64.0% from thermal, 29.9% from hydroelectric power, and ~0.3% from the Coal source.[283]

Tourism

Pakistan, with its diverse cultures, people and landscapes attracted 1 million tourists in 2012.[286] Pakistan's tourism industry was in its heyday during the 1970s when the country received unprecedented amounts of foreign tourists. The main destinations of choice for these tourists were the Khyber Pass, Peshawar, Karachi, Lahore, Swat and Rawalpindi.[287] The country's attraction range from the ruin of civilisation such as Mohenjo-daro, Harappa and Taxila, to the Himalayan hill stations. Pakistan is home to several mountain peaks over 7000 m.[288]

The north part of Pakistan has many old fortresses, ancient architecture and the Hunza and Chitral valley, home to small pre-Islamic Animist Kalasha community claiming descent from Alexander the Great. Other attractions include the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, Punjab province. Pakistan's cultural capital, with many examples of Mughal architecture such as Badshahi Masjid, Shalimar Gardens, Tomb of Jahangir and the Lahore Fort. Before the Global economic crisis Pakistan received more than 500,000 tourists annually.[289] However, this number has now come down to near zero figures since 2008 due to instability in the country and many countries declaring Pakistan as unsafe and dangerous to visit.

In October 2006, just one year after the 2005 Kashmir earthquake, The Guardian released what it described as "The top five tourist sites in Pakistan" in order to help the country's tourism industry.[290] The five sites included Taxila, Lahore, The Karakoram Highway, Karimabad and Lake Saiful Muluk. To promote Pakistan's unique and various cultural heritage.[291][292] In 2009, The World Economic Forum's Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report ranked Pakistan as one of the top 25% tourist destinations for its World Heritage sites. Ranging from mangroves in the South, to the 5,000-year-old cities of the Indus Valley Civilization which included Mohenjo-daro and Harappa.[293]

Transport

The transport industry accounts for ~10.5% of nation's GDP.[294] Pakistan's motorway infrastructure is better than those of India, Bangladesh, and Indonesia, but the train system lags behind those of India and China, and aviation infrastructure also needs improvement.[295] There is scarcely any inland water transportation system, and coastal shipping only meets minor local requirements.[296]

Highways form the backbone of Pakistan's transport system; a total road length of 259,618 km accounts for 91% of passenger and 96% of freight traffic. Road transport services are largely in the hands of the private sector, which handles around 95% of freight traffic. The National Highway Authority is responsible for the maintenance of national highways and motorways. The highway and motorway system depends mainly on north–south links, connecting the southern ports to the populous provinces of Punjab and Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa. Although this network only accounts for 4.2% of total road length, it carries 85% of the country's traffic.[297][298]

The Pakistan Railways, under the Ministry of Railways (MoR), operates the railroad system. From 1947 until 1970s, the train system was the primary means of transport until the nationwide constructions of the national highways and the economic boom of the automotive industry. Since 1990s, there was a marked shift in traffic from rail to highways; dependence grew on roads after the introduction of vehicles in the country. Now the railway's share of inland traffic is only 10% for passengers and 4% for freight traffic. Personal transportation dominated by the automobiles, the total rail track decreased from 8,775 km in 1990–91 to 7,791 km in 2011.[297][299] Pakistan expects to use the rail service to boost foreign trade with China, Iran and Turkey.[300][301]

Rough estimates accounts for 139 airports in Pakistan–both military and civilian airports which are mostly are publicly owned. Though the Jinnah International Airport is the principal international gateway to Pakistan, the international airports in Lahore, Islamabad, Peshawar, Quetta, Faisalabad, Sialkot and Multan also handle significant amounts of traffic. The civil aviation industry is mixed with public and private sectors, which has been deregulated in 1993. While the state-owned Pakistan International Airlines (PIA) is the major and dominated air carrier that carries about 73% of domestic passengers and all domestic freight, the private airlines such as airBlue, Shaheen Air International, and Air Indus, also provide the similar services with low cost expenses. Major seaports are in Karachi, Sindh (the Karachi port and Port Qasim).[297][299] Since 1990s, the seaport operations have been moved to Balochistan with the construction of Gwadar Port and Gadani Port.[297][299]

Science and technology

Development on science and technology plays an influential role in Pakistan's infrastructure and helped the country to reach out to the world.[302] Every year, scientists from around the world are invited by the Pakistan Academy of Sciences and the Pakistan Government to participate in the International Nathiagali Summer College on Physics.[303] Pakistan hosted an international seminar on Physics in Developing Countries for International Year of Physics 2005.[304] Pakistani theoretical physicist Abdus Salam won a Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on the electroweak interaction.[305] Influential publications and the critical scientific works in the advancement of mathematics, biology, economics, computer science, and genetics have been produced by the Pakistani scientists at the domestic and international standings.[306]

In chemistry, Salimuzzaman Siddiqui was the first Pakistani scientist to bring the therapeutic constituents of the Neem tree to the attention of natural products chemists.[307][308][309] Pakistani neurosurgeon Ayub Ommaya invented the Ommaya reservoir, a system for treatment of brain tumours and other brain conditions.[310] Scientific research and development plays a pivotal role in Pakistani universities, collaboration with the government sponsored national laboratories, science parks, and co-operation with the industry.[311] In 2010, Pakistan was ranked 43rd in the world in terms of published scientific papers.[312] The Pakistan Academy of Sciences, a strong scientific community, plays an influential and vital role in formulating the science policies recommendation to the government.[313]

The 1960s era saw the emergence of the active space program led by the SUPARCO that produced advances in domestic rocketry, electronics, and aeronomy.[314] The space program recorded few notable feats and achievements; the successful launch of the first rocket into the space that made Pakistan as first South Asian country to achieve such task.[314] Successfully producing and launching nation's first space satellite in 1990, Pakistan became the first Muslim country and second South Asian country to put a satellite into space.[315]

As an aftermath of the 1971 war with India, the clandestine crash program developed atomic weapons in a fear and to prevent any foreign intervention, while ushering in the atomic age in the post cold war era.[119] Competition with India and tensions eventually led Pakistan's decision of conducting underground nuclear tests in 1998; thus becoming the seventh country in the world to successfully develop nuclear weapons.[316]

After establishing an Antarctic program, Pakistan is one of the small number of countries that have an active research presence in Antarctica. The Antarctic program oversees two summer research stations on the continent and plans to open another base, which will operate all year round.[317] Energy consumption by computers and usage has grown since 1990s when the PCs were introduced; Pakistan has over 20 million internet users and is ranked as one of the top countries that have registered a high growth rate in internet penetration, as of 2011.[318] Key publications has been produced by Pakistan, and domestic software development has gained a lot international praise.[319]

Overall, it has the 27th largest population of internet users in the world. Since 2000s, Pakistan has made significant amount of progress in supercomputing, and various institutions offers research in parallel computing. Pakistan government reportedly spends ₨. 4.6 billion on information technology projects, with emphasis on e-government, human resource and infrastructure development.[320]

| Prominent Pakistani Inventions | Detail |

|---|---|

| Ommaya reservoir | System for the delivery of drugs into the cerebrospinal fluid for treatment of patients with brain tumours. |

| (c)Brain | One of the first computer viruses in history |

| Electroweak interaction | Discovery led Muslim world's first Nobel Prize in Physics. |

| Plastic magnet | World's first workable plastic magnet at room temperature. |

| Non-lethal fertilizer | A formula to make fertilizers that cannot be converted into bomb-making materials. |

| Non-Kink Catheter Mount | A crucial instrument used in anesthesiology. |

| Human Development Index | Devised by Pakistan's former finance minister, Mahbub ul Haq.[321] |

| Standard Model | Particle physics theory devised part by Pakistan scientist Abdus Salam |

Education

The Constitution of Pakistan requires the state to provide free primary and secondary education.[323][324] At the time of establishment of Pakistan as state, the country had only one university, the Punjab University in Lahore.[325] On immediate basis, the Pakistan government established public universities in each four provinices including the Sindh University (1949), Peshawar University (1950), Karachi University (1953), and Balochistan University (1970). As of September 2011, Pakistan has a large network of both public and private universities; a collaboration of public-private universities to provide research and higher education in the country.[326] It is estimated that there are 3193 technical and vocational institutions in Pakistan,[327] and there are also madrassahs that provide free Islamic education and offer free board and lodging to students, who come mainly from the poorer strata of society.[328] Strongly instigated public pressure and popular criticism over the extremists usage of madrassahs for recruitment, the Pakistan government has made repeated efforts to regulate and monitor the quality of education in the madrassahs.[329][330]

Education in Pakistan is divided into six main levels: nursery (preparatory classes); primary (grades one through five); middle (grades six through eight); matriculation (grades nine and ten, leading to the secondary certificate); intermediate (grades eleven and twelve, leading to a higher secondary certificate); and university programmes leading to graduate and postgraduate programs.[327] Network of Pakistani private schools also operate a parallel secondary education system based on the curriculum set and administered by the Cambridge International Examinations of the United Kingdom. Some students choose to take the O-level and A level exams conducted by the British Council.[331]

Initiatives taken in 2007, the English medium education has been made compulsory to all schools across the country.[332][333] Additional reforms taken in 2013, all educational institutions in Sindh began instructions in Chinese language courses, reflecting China's growing role as a superpower and increasing influence in Pakistan.[334] The literacy rate of the population above ten years of age in the country is ~58.5%. Male literacy is ~70.2% while female literacy rate is 46.3%.[245] Literacy rates vary by region and particularly by sex; for instance, female literacy in tribal areas is 3.0%.[335] With the launch of the computer literacy in 1995, the government launched a nationwide initiative in 1998 with the aim of eradicating illiteracy and providing a basic education to all children.[336] Through various educational reforms, by 2015 the MoEd expects to attain 100.00% enrollment levels among children of primary school age and a literacy rate of ~86% among people aged over 10.[337]

After earning their HSC, students may study in a professional college or the university for bachelorate program courses such as science and engineering (BEng, BS/BSc, BTech) surgery and medicine (MBBS, MD), dentistry (BDS), veterinary medicine (DVM), criminal justice and law (LLB, LLM, JD), architecture (BArch), pharmacy (Pharm D.) and nursing (BNurs). Students can also attend a university for a bachelorate degree for business administration, literature, and management including the BA, BCom, BBA, and MBA programs. The higher education mainly supervises by the Higher Education Commission (HEC) that sets out the policies and issues rankings of the nationwide universities. In October 2014, education activist Malala Yousafzai became by far the youngest ever person in the world to receive the Nobel peace prize.[338]

Demographics

Unofficial Pakistan Census estimates the country's population at ~188,144,040 (188.1 million) as of 2015, which is equivalent to 2.57% of the world population.[339] Noted as the sixth most populated country in the world, its growth rate is reported at ~2.03%, which is the highest of the SAARC nations and gives an annual increase of 3.6 million. The population is projected to reach 210.13 million by 2020 and to double by 2045.

At the time of the partition in 1947, Pakistan had a population of 32.5 million,[251][340] but the population increased by ~57.2% between the years 1990 and 2009.[341] By 2030, it is expected to surpass Indonesia as the largest Muslim-majority country in the world.[342][343] Pakistan is classified as a "young nation" with a median age of about 22, and 104 million people under the age of 30 in 2010. Pakistan's fertility rate stands at 3.07, higher than its neighbors India (2.57) and Iran (1.73). Around 35% of the people are under 15.[251]

Vast majority residing in southern skirts lives along the Indus River, with Karachi being its most populous commercial city.[344] In the eastern, western, and northern skirts, most of the population lives in an arc formed by the cities of Lahore, Faisalabad, Rawalpindi, Sargodha, Islamabad, Gujranwala, Sialkot, Gujrat, Jhelum, Sheikhupura, Nowshera, Mardan and Peshawar.[106] During 1990–2008, the city dwellers made up 36% of Pakistan's population, making it the most urbanised nation in South Asia.[106][251] Furthermore, 50% of Pakistanis live in towns of 5,000 people or more.[345]

Expenditure spend on healthcare was ~2.6% of GDP in 2009.[346] Life expectancy at birth was 65.4 years for females and 63.6 years for males in 2010. The private sector accounts for about 80% of outpatient visits. Approximately 19% of the population and 30% of children under five are malnourished.[232] Mortality of the under-fives was 87 per 1,000 live births in 2009.[346] About 20% of the population live below the international poverty line of US$1.25 a day.[347]

| Social groups | Populations in millions (Numerics and % Change) |

|---|---|

| Punjabis | 76.3(+44.15%) |

| Pashtuns | 29.3(+15.42%) |

| Sindhis | 24.8(+14.10%) |

| Balochs | 6.9(+3.57%) |

| Seraikis | 14.8(+10.53%) |

| Muhajirs | 13.3(+7.57 %) |

| Others | 11.1(-4.66%) |