Paixhans gun

| Paixhans gun (Canon Paixhans) | |

|---|---|

|

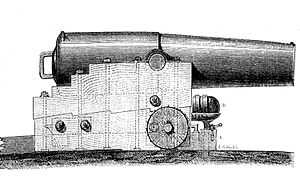

Paixhans naval shell gun. Musée de la Marine. | |

| Type | Naval artillery |

| Place of origin | France |

| Service history | |

| Used by | France, United States, Russia |

| Wars | Second Opium War, Anglo-French blockade of the Río de la Plata, Mexican-American War, Danish-Prussian War, Crimean War, American Civil War |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Henri-Joseph Paixhans |

| Designed | 1823 |

| Specifications | |

| Weight | 7,400 lbs |

| Length | 9 feet 4 inches[1] |

|

| |

| Shell | 30 kg (59 lb.) shell |

| Caliber | 22 cm (8.7-inch)[1] |

| Muzzle velocity | 400 m/s (1,200 ft/s) |

The Paixhans gun (French: Canon Paixhans) was the first naval gun designed to fire explosive shells. It was developed by the French general Henri-Joseph Paixhans in 1822-1823.

Background

Explosive shells had long been in use in ground warfare (in howitzers and mortars), but they were only fired at high angles and with relatively low velocities. Shells are inherently dangerous to handle, and no method had been found to combine the explosive character of the shells with the high power and flatter trajectory of a high velocity gun.

However, before the advent of radar and modern optical controlled firing, high trajectories were not practical for marine combat. Naval combat essentially required flat-trajectory guns in order to have some decent odds of hitting the target. Therefore naval warfare had consisted for centuries of encounters between flat-trajectory cannons using inert cannonballs, which could inflict only local damage even on wooden hulls.[2]

Mechanism

Paixhans advocated using flat-trajectory shell guns against warships in 1822 in his Nouvelle force maritime et artillerie.[3]

Paixhans developed a delaying mechanism which, for the first time, allowed shells to be fired safely in high-powered flat-trajectory guns. The effect of explosive shells lodging into wooden hulls and then detonating, was potentially devastating. This was first demonstrated by Henri-Joseph Paixhans in trials against the two-decker Pacificateur in 1824, in which he successfully broke up the ship.[2] Two prototype Paixhans guns had been founded in 1823 and 1824 for this test. Paixhans reported the results in Experiences faites sur une arme nouvelle.[3] The shells were equipped with a fuse which ignited automatically when the gun was fired. The shell would then lodge itself in the wooden hull of the target, before exploding a moment later:

The shells which produced those very extensive ravages upon the Pacificator hulk in the experiments made at Brest, in 1821 and 1824, upon the evidences of which the French naval shell system was founded, were loaded shells, having fuzes attached, which, ignited by the explosion of the discharge in the gun, continued to burn for a time somewhat greater than that of the estimated flight, and then exploded; thus producing the maximum effect which any shell is capable of producing on a ship.—A treatise on naval gunnery by Sir Howard Douglas.[4]

The first Paixhans guns for the French Navy were founded in 1841. The barrel of the guns weighed about 10,000 lbs. (4.5 metric tons), and proved accurate to about two miles. In the 1840s, France, England, Russia and the United States adopted the new naval guns.

The effect of the guns in an operational context was first demonstrated during the actions at Veracruz in 1838, Eckernförde in 1849 during the Danish-Prussian War, and especially at the Battle of Sinop in 1853 during the Crimean War.

According to the Penny Cyclopaedia (1858):

General Paixhans made important improvements in the construction of heavy ordnance, and also in the projectiles, in the carriages, and in the mode of working the guns. The Paixhans-guns are especially adapted for the projection of shells and hollow shot, and were first adopted in France about the year 1824. Similar pieces of ordnance have since been introduced into the British service. They are suitable either for ships of war, or for fortresses which defend coasts. The original Paixhans-gun was 9 feet 4 inches long [2.84 m], and weighed nearly 74 cwts [3,800 kg]. The bore was 22 centimetres (8 inches nearly). By judicious distribution of the metal it was so much strengthened about the chamber, or place of charge, that it could bear firing with solid shot weighing from 86 to 88 lbs [39-40 kg], or with hollow shot weighing about 60 lbs [27 kg]. The charge varied from 10 lbs. 12 oz to 18 lbs [4.9-8.2 kg] of powder. General Paixhans was one of the first to recommend cylindro-conical projectiles, as having the advantage of encountering less resistance from the air than round balls, having a more direct flight, and striking the object aimed at with much greater force, when discharged from a piece of equal calibre, whether musket or great gun. As large ships of war, particularly three-decked ships, offer a mark which can hardly be missed, even at considerable distances, and as their wooden walls are so thick and strong that a shell projected horizontally could not pass through them, an explosion taking place would produce the destructive effects of springing a mine, and far exceeding those of a shell projected vertically, and acting by concussion or percussion.—Penny Cyclopedia[1]

Adoption

France

In 1827 the French navy ordered fifty large guns on the Paixhans model from the arsenals at Ruelle and at Indret near Nantes. The gun chosen, the canon-obusier de 80, was so called because it was of the 22 cm bore diameter which would have fired an 80 pound solid shot. The gun barrel weighed 3600 kg and the bore was of 223 mm diameter and 2.8 m long, firing a shell weighing 23.12 kg. The guns were produced slowly and were tested afloat through the 1830s. They formed a small part of the armament on larger ships, with two or four guns only being carried, although on smaller, experimental steam vessels they, and the much larger canon-obusier de 150, of 27 cm bore, were proportionately more important, the paddle steamer Météore, for example, carrying three canon-obusier de 80 pieces and six small carronades in 1833. Alongside the large guns which Paixhans had called for, the French navy also used a smaller shell gun, of the same 164 mm bore as its standard solid shot-firing 30 pounder guns and carronades, in larger numbers with first rate ships carrying over 30 of these guns.[5][6]

United States

The United States Navy adopted the design, and equipped several ships with 8-inch guns of 63 and 55 cwt. In 1845, and later a 10-inch shell gun of 86 cwt. Paixhans guns were used on USS Constitution (4 Paixhans guns) in 1842, under the command of Foxhall A. Parker, Sr., and were also present on board the USS Mississippi (10 Paixhans guns), and USS Susquehanna (6 Paixhans guns) during Commodore Perry's mission to open Japan in 1853.[7][8]

The Dahlgren gun was developed by John A. Dahlgren in 1849 to supersede Paixhans guns:

Paixhans had so far satisfied naval men of the power of shell guns as to obtain their admission on shipboard; but by unduly developing the explosive element, he had sacrificed accuracy and range.... The difference between the system of Paixhans and my own was simply that Paixhans guns were strictly shell guns, and were not designed for shot, nor for great penetration or accuracy at long ranges. They were, therefore, auxiliary to, or associates of, the shot-guns. This made a mixed armament, was objectionable as such, and never was adopted to any extent in France... My idea was, to have a gun that should generally throw shells far and accurately, with the capacity to fire solid shot when needed. Also to compose the whole battery entirely of such guns.—Admiral John A. Dahlgren.[9]

Russia

The Russian Navy was the first to use the guns extensively in combat. At the Battle of Sinop in 1853, Russian ships attacked and annihilated a Turkish fleet with their Paixhans explosive shell guns.[10] The shell penetrated deep inside the wooden planking of Turkish ships, exploding and igniting the hulls.[2] The defeat was instrumental in convincing the naval powers of the shell's efficacy, and hastened the development of the ironclad to counter it.[10]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Penny cyclopaedia of the Society for the diffusion of useful knowledge, p.487

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Of arms and men Robert L. O'Connell p.193

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Artillery Jeff Kinards , Spencer C. (INT) Tucker p.235-236

- ↑ A treatise on naval gunnery by Sir Howard Douglas p.297

- ↑ Boudriot, Jean (1988), "Vaisseaux et frégates sous la Restauration et la Monarchie de Juillet", Marine et technique au XIXe siècle, Service historique de la Marine/Institut d'histoire des conflits contemporains, pp. 65 83

- ↑ Adams, Thomas (1988), "Artillerie et obus", Marine et technique au XIXe siècle, Service historique de la Marine/Institut d'histoire des conflits contemporains, pp. 191 200

- ↑ Arms and men: a study in American military history Walter Millis p.88

- ↑ Black Ships Off Japan - The Story of Commodore Perry's Expedition Arthur Walworth p.21

- ↑ Admiral John A. Dahlgren: Father of United States Naval Ordance - Page 26 by Clarence Stewart Peterson, John Adolphus Bernard Dahlgren, 1945

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Sea Power: A Naval History, 2nd Edition E.B. Potter (INT) p.157

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||