Pairwise summation

In numerical analysis, pairwise summation, also called cascade summation, is a technique to sum a sequence of finite-precision floating-point numbers that substantially reduces the accumulated round-off error compared to naively accumulating the sum in sequence.[1] Although there are other techniques such as Kahan summation that typically have even smaller round-off errors, pairwise summation is nearly as good (differing only by a logarithmic factor) while having much lower computational cost—it can be implemented so as to have nearly the same cost (and exactly the same number of arithmetic operations) as naive summation.

In particular, pairwise summation of a sequence of n numbers xn works by recursively breaking the sequence into two halves, summing each half, and adding the two sums: a divide and conquer algorithm. Its worst-case roundoff errors grow asymptotically as at most O(ε log n), where ε is the machine precision (assuming a fixed condition number, as discussed below).[1] In comparison, the naive technique of accumulating the sum in sequence (adding each xi one at a time for i = 1, ..., n) has roundoff errors that grow at worst as O(εn).[1] Kahan summation has a worst-case error of roughly O(ε), independent of n, but requires several times more arithmetic operations.[1] If the roundoff errors are random, and in particular have random signs, then they form a random walk and the error growth is reduced to an average of  for pairwise summation.[2]

for pairwise summation.[2]

A very similar recursive structure of summation is found in many fast Fourier transform (FFT) algorithms, and is responsible for the same slow roundoff accumulation of those FFTs.[2][3]

Pairwise summation is the default summation algorithm in NumPy[4] and the Julia technical-computing language,[5] where in both cases it was found to have comparable speed to naive summation (thanks to the use of a large base case).

The algorithm

In pseudocode, the pairwise summation algorithm for an array x of length n > 0 can be written:

s = pairwise(x[1…n]) if n ≤ N base case: naive summation for a sufficiently small array s = x[1] for i = 2 to n s = s + x[i] else divide and conquer: recursively sum two halves of the array m = floor(n / 2) s = pairwise(x[1…m]) + pairwise(x[m+1…n]) endif

For some sufficiently small N, this algorithm switches to a naive loop-based summation as a base case, whose error bound is O(ε). The entire sum has a worst-case error that grows asymptotically as O(ε log n) for large n, for a given condition number (see below).

In an algorithm of this sort (as for divide and conquer algorithms in general[6]), it is desirable to use a larger base case in order to amortize the overhead of the recursion. If N = 1, then there is roughly one recursive subroutine call for every input, but more generally there is one recursive call for (roughly) every N/2 inputs if the recursion stops at exactly n = N. By making N sufficiently large, the overhead of recursion can be made negligible (precisely this technique of a large base case for recursive summation is employed by high-performance FFT implementations[3]).

Regardless of N, exactly n−1 additions are performed in total, the same as for naive summation, so if the recursion overhead is made negligible then pairwise summation has essentially the same computational cost as for naive summation.

A variation on this idea is to break the sum into b blocks at each recursive stage, summing each block recursively, and then summing the results, which was dubbed a "superblock" algorithm by its proposers.[7] The above pairwise algorithm corresponds to b = 2 for every stage except for the last stage which is b = N.

Accuracy

Suppose that one is summing n values xi, for i = 1, ..., n. The exact sum is:

(computed with infinite precision).

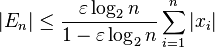

With pairwise summation for a base case N = 1, one instead obtains  , where the error

, where the error  is bounded above by:[1]

is bounded above by:[1]

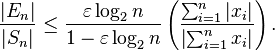

where ε is the machine precision of the arithmetic being employed (e.g. ε ≈ 10−16 for standard double precision floating point). Usually, the quantity of interest is the relative error  , which is therefore bounded above by:

, which is therefore bounded above by:

In the expression for the relative error bound, the fraction (Σ|xi|/|Σxi|) is the condition number of the summation problem. Essentially, the condition number represents the intrinsic sensitivity of the summation problem to errors, regardless of how it is computed.[8] The relative error bound of every (backwards stable) summation method by a fixed algorithm in fixed precision (i.e. not those that use arbitrary-precision arithmetic, nor algorithms whose memory and time requirements change based on the data), is proportional to this condition number.[1] An ill-conditioned summation problem is one in which this ratio is large, and in this case even pairwise summation can have a large relative error. For example, if the summands xi are uncorrelated random numbers with zero mean, the sum is a random walk and the condition number will grow proportional to  . On the other hand, for random inputs with nonzero mean the condition number asymptotes to a finite constant as

. On the other hand, for random inputs with nonzero mean the condition number asymptotes to a finite constant as  . If the inputs are all non-negative, then the condition number is 1.

. If the inputs are all non-negative, then the condition number is 1.

Note that the  denominator is effectively 1 in practice, since

denominator is effectively 1 in practice, since  is much smaller than 1 until n becomes of order 21/ε, which is roughly 101015 in double precision.

is much smaller than 1 until n becomes of order 21/ε, which is roughly 101015 in double precision.

In comparison, the relative error bound for naive summation (simply adding the numbers in sequence, rounding at each step) grows as  multiplied by the condition number.[1] In practice, it is much more likely that the rounding errors have a random sign, with zero mean, so that they form a random walk; in this case, naive summation has a root mean square relative error that grows as

multiplied by the condition number.[1] In practice, it is much more likely that the rounding errors have a random sign, with zero mean, so that they form a random walk; in this case, naive summation has a root mean square relative error that grows as  and pairwise summation as an error that grows as

and pairwise summation as an error that grows as  on average.[2]

on average.[2]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Higham, Nicholas J. (1993), "The accuracy of floating point summation", SIAM Journal on Scientific Computing 14 (4): 783–799, doi:10.1137/0914050

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Manfred Tasche and Hansmartin Zeuner Handbook of Analytic-Computational Methods in Applied Mathematics Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2000).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 S. G. Johnson and M. Frigo, "Implementing FFTs in practice, in Fast Fourier Transforms, edited by C. Sidney Burrus (2008).

- ↑ ENH: implement pairwise summation, github.com/numpy/numpy pull request #3685 (September 2013).

- ↑ RFC: use pairwise summation for sum, cumsum, and cumprod, github.com/JuliaLang/julia pull request #4039 (August 2013).

- ↑ Radu Rugina and Martin Rinard, "Recursion unrolling for divide and conquer programs," in Languages and Compilers for Parallel Computing, chapter 3, pp. 34–48. Lecture Notes in Computer Science vol. 2017 (Berlin: Springer, 2001).

- ↑ Anthony M. Castaldo, R. Clint Whaley, and Anthony T. Chronopoulos, "Reducing floating-point error in dot product using the superblock family of algorithms," SIAM J. Sci. Comput., vol. 32, pp. 1156–1174 (2008).

- ↑ L. N. Trefethen and D. Bau, Numerical Linear Algebra (SIAM: Philadelphia, 1997).