p-adic Hodge theory

In mathematics, p-adic Hodge theory is a theory that provides a way to classify and study p-adic Galois representations of characteristic 0 local fields[1] with residual characteristic p (such as Qp). The theory has its beginnings in Jean-Pierre Serre and John Tate's study of Tate modules of abelian varieties and the notion of Hodge–Tate representation. Hodge–Tate representations are related to certain decompositions of p-adic cohomology theories analogous to the Hodge decomposition, hence the name p-adic Hodge theory. Further developments were inspired by properties of p-adic Galois representations arising from the étale cohomology of varieties. Jean-Marc Fontaine introduced many of the basic concepts of the field.

General classification of p-adic representations

Let K be a local field of residue field k of characteristic p. In this article, a p-adic representation of K (or of GK, the absolute Galois group of K) will be a continuous representation ρ : GK→ GL(V) where V is a finite-dimensional vector space over Qp. The collection of all p-adic representations of K form an abelian category denoted  in this article. p-adic Hodge theory provides subcollections of p-adic representations based on how nice they are, and also provides faithful functors to categories of linear algebraic objects that are easier to study. The basic classification is as follows:[2]

in this article. p-adic Hodge theory provides subcollections of p-adic representations based on how nice they are, and also provides faithful functors to categories of linear algebraic objects that are easier to study. The basic classification is as follows:[2]

where each collection is a full subcategory properly contained in the next. In order, these are the categories of crystalline representations, semistable representations, de Rham representations, Hodge–Tate representations, and all p-adic representations. In addition, two other categories of representations can be introduced, the potentially crystalline representations Reppcris(K) and the potentially semistable representations Reppst(K). The latter strictly contains the former which in turn generally strictly contains Repcris(K); additionally, Reppst(K) generally strictly contains Repst(K), and is contained in RepdR(K) (with equality when the residue field of K is finite, a statement called the p-adic monodromy theorem).

Period rings and comparison isomorphisms in arithmetic geometry

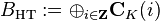

The general strategy of p-adic Hodge theory, introduced by Fontaine, is to construct certain so-called period rings[3] such as BdR, Bst, Bcris, and BHT which have both an action by GK and some linear algebraic structure and to consider so-called Dieudonné modules

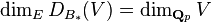

(where B is a period ring, and V is a p-adic representation) which no longer have a GK-action, but are endowed with linear algebraic structures inherited from the ring B. In particular, they are vector spaces over the fixed field  .[4] This construction fits into the formalism of B-admissible representations introduced by Fontaine. For a period ring like the aforementioned ones B∗ (for ∗ = HT, dR, st, cris), the category of p-adic representations Rep∗(K) mentioned above is the category of B∗-admissible ones, i.e. those p-adic representations V for which

.[4] This construction fits into the formalism of B-admissible representations introduced by Fontaine. For a period ring like the aforementioned ones B∗ (for ∗ = HT, dR, st, cris), the category of p-adic representations Rep∗(K) mentioned above is the category of B∗-admissible ones, i.e. those p-adic representations V for which

or, equivalently, the comparison morphism

is an isomorphism.

This formalism (and the name period ring) grew out of a few results and conjectures regarding comparison isomorphisms in arithmetic and complex geometry:

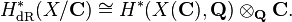

- If X is a proper smooth scheme over C, there is a classical comparison isomorphism between the algebraic de Rham cohomology of X over C and the singular cohomology of X(C)

- This isomorphism can be obtained by considering a pairing obtained by integrating differential forms in the algebraic de Rham cohomology over cycles in the singular cohomology. The result of such an integration is called a period and is generally a complex number. This explains why the singular cohomology must be tensored to C, and from this point of view, C can be said to contain all the periods necessary to compare algebraic de Rham cohomology with singular cohomology, and could hence be called a period ring in this situation.

- In the mid sixties, Tate conjectured[5] that a similar isomorphism should hold for proper smooth schemes X over K between algebraic de Rham cohomology and p-adic étale cohomology (the Hodge–Tate conjecture, also called CHT). Specifically, let CK be the completion of an algebraic closure of K, let CK(i) denote CK where the action of GK is via g·z = χ(g)ig·z (where χ is the p-adic cyclotomic character, and i is an integer), and let

. Then there is a functorial isomorphism

. Then there is a functorial isomorphism

- of graded vector spaces with GK-action (the de Rham cohomology is equipped with the Hodge filtration, and

is its associated graded). This conjecture was proved by Gerd Faltings in the late eighties[6] after partial results by several other mathematicians (including Tate himself).

is its associated graded). This conjecture was proved by Gerd Faltings in the late eighties[6] after partial results by several other mathematicians (including Tate himself).

- For an abelian variety X with good reduction over a p-adic field K, Alexander Grothendieck reformulated a theorem of Tate's to say that the crystalline cohomology H1(X/W(k)) ⊗ Qp of the special fiber (with the Frobenius endomorphism on this group and the Hodge filtration on this group tensored with K) and the p-adic étale cohomology H1(X,Qp) (with the action of the Galois group of K) contained the same information. Both are equivalent to the p-divisible group associated to X, up to isogeny. Grothendieck conjectured that there should be a way to go directly from p-adic étale cohomology to crystalline cohomology (and back), for all varieties with good reduction over p-adic fields.[7] This suggested relation became known as the mysterious functor.

To improve the Hodge–Tate conjecture to one involving the de Rham cohomology (not just its associated graded), Fontaine constructed[8] a filtered ring BdR whose associated graded is BHT and conjectured[9] the following (called CdR) for any smooth proper scheme X over K

as filtered vector spaces with GK-action. In this way, BdR could be said to contain all (p-adic) periods required to compare algebraic de Rham cohomology with p-adic étale cohomology, just as the complex numbers above were used with the comparison with singular cohomology. This is where BdR obtains its name of ring of p-adic periods.

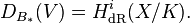

Similarly, to formulate a conjecture explaining Grothendieck's mysterious functor, Fontaine introduced a ring Bcris with GK-action, a "Frobenius" φ, and a filtration after extending scalars from K0 to K. He conjectured[10] the following (called Ccris) for any smooth proper scheme X over K with good reduction

as vector spaces with φ-action, GK-action, and filtration after extending scalars to K (here  is given its structure as a K0-vector space with φ-action given by its comparison with crystalline cohomology). Both the CdR and the Ccris conjectures were proved by Faltings.[11]

is given its structure as a K0-vector space with φ-action given by its comparison with crystalline cohomology). Both the CdR and the Ccris conjectures were proved by Faltings.[11]

Upon comparing these two conjectures with the notion of B∗-admissible representations above, it is seen that if X is a proper smooth scheme over K (with good reduction) and V is the p-adic Galois representation obtained as is its ith p-adic étale cohomology group, then

In other words, the Dieudonné modules should be thought of as giving the other cohomologies related to V.

In the late eighties, Fontaine and Uwe Jannsen formulated another comparison isomorphism conjecture, Cst, this time allowing X to have semi-stable reduction. Fontaine constructed[12] a ring Bst with GK-action, a "Frobenius" φ, a filtration after extending scalars from K0 to K (and fixing an extension of the p-adic logarithm), and a "monodromy operator" N. When X has semi-stable reduction, the de Rham cohomology can be equipped with the φ-action and a monodromy operator by its comparison with the log-crystalline cohomology first introduced by Osamu Hyodo.[13] The conjecture then states that

as vector spaces with φ-action, GK-action, filtration after extending scalars to K, and monodromy operator N. This conjecture was proved in the late nineties by Takeshi Tsuji.[14]

Notes

- ↑ In this article, a local field is complete discrete valuation field whose residue field is perfect.

- ↑ Fontaine 1994, p. 114

- ↑ These rings depend on the local field K in question, but this relation is usually dropped from the notation.

- ↑ For B = BHT, BdR, Bst, and Bcris,

is K, K, K0, and K0, respectively, where K0 = Frac(W(k)), the fraction field of the Witt vectors of k.

is K, K, K0, and K0, respectively, where K0 = Frac(W(k)), the fraction field of the Witt vectors of k. - ↑ See Serre 1967

- ↑ Faltings 1988

- ↑ Grothendieck 1971, p. 435

- ↑ Fontaine 1982

- ↑ Fontaine 1982, Conjecture A.6

- ↑ Fontaine 1982, Conjecture A.11

- ↑ Faltings 1989

- ↑ Fontaine 1994, Exposé II, section 3

- ↑ Hyodo 1991

- ↑ Tsuji 1999

References

Primary sources

- Faltings, Gerd (1988), "p-adic Hodge theory", Journal of the American Mathematical Society 1 (1): 255–299, doi:10.2307/1990970, MR 0924705

- Faltings, Gerd, "Crystalline cohomology and p-adic Galois representations", in Igusa, Jun-Ichi, Algebraic analysis, geometry, and number theory, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 25–80, ISBN 978-0-8018-3841-5, MR 1463696

- Fontaine, Jean-Marc (1982), "Sur certains types de représentations p-adiques du groupe de Galois d'un corps local; construction d'un anneau de Barsotti–Tate", Annals of Mathematics 115 (3): 529–577, doi:10.2307/2007012, MR 0657238

- Grothendieck, Alexander (1971), "Groupes de Barsotti–Tate et cristaux", Actes du Congrès International des Mathématiciens (Nice, 1970) 1, pp. 431–436, MR 0578496

- Hyodo, Osamu (1991), "On the de Rham–Witt complex attached to a semi-stable family", Compositio Mathematica 78 (3): 241–260, MR 1106296

- Serre, Jean-Pierre (1967), "Résumé des cours, 1965–66", Annuaire du Collège de France, Paris, pp. 49–58

- Tsuji, Takeshi (1999), "p-adic étale cohomology and crystalline cohomology in the semi-stable reduction case", Inventiones Mathematicae 137 (2): 233–411, doi:10.1007/s002220050330, MR 1705837

Secondary sources

- Berger, Laurent (2004), "An introduction to the theory of p-adic representations", Geometric aspects of Dwork theory I, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG, arXiv:math/0210184, ISBN 978-3-11-017478-6, MR 2023292

- Brinon, Olivier; Conrad, Brian (2009), CMI Summer School notes on p-adic Hodge theory, retrieved 2010-02-05

- Fontaine, Jean-Marc, ed. (1994), Périodes p-adiques, Astérisque 223, Paris: Société Mathématique de France, MR 1293969

- Illusie, Luc (1990), "Cohomologie de de Rham et cohomologie étale p-adique (d'après G. Faltings, J.-M. Fontaine et al.) Exp. 726", Séminaire Bourbaki. Vol. 1989/90. Exposés 715–729, Astérisque, 189–190, Paris: Société Mathématique de France, pp. 325–374, MR 1099881