Owain Gwynedd

| Owain Gwynedd | |

|---|---|

| Prince of Gwynedd | |

|

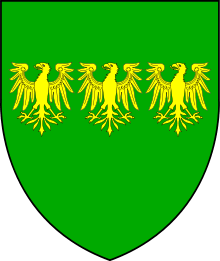

The coat of arms retroactively attributed to Owain Gwynedd were: Vert, three eagles displayed in fess Or | |

| King of All Wales | |

| Predecessor | Gruffudd ap Cynan |

| Successor | Rhys ap Gruffydd |

| King of Gwynedd | |

| Reign | 1137-1170 |

| Predecessor | Gruffudd ap Cynan |

| Successor | Hywel ab Owain Gwynedd |

| Spouse | Gwladus ferch Llywarch, Cristin ferch Goronwy |

| Issue |

Rhun ab Owain Gwynedd Hywel ab Owain Gwynedd Iorwerth "Drwyndwn" ab Owain Gwynedd Maelgwn ab Owain Gwynedd Gwenllian ferch Owain Gwynedd Dafydd ab Owain Gwynedd Rhodri ab Owain Gwynedd Angharad ferch Owain Gwynedd Margaret ferch Owain Gwynedd Iefan ferch Owain Gwynedd Cynan ab Owain Gwynedd Rhirid ab Owain Gwynedd Rhirid ab Owain Gwynedd Madoc ab Owain Gwynedd Cynwrig ab Owain Gwynedd Gwenllian ferch Owain Gwynedd Einion ab Owain Gwynedd Iago ab Owain Gwynedd Ffilip ab Owain Gwynedd Cadell ab Owain Gwynedd Rotpert ab Owain Gwynedd Idwal ab Owain Gwynedd |

| House | House of Aberffraw |

| Father | Gruffudd ap Cynan |

| Mother | Angharad ferch Owain |

| Born |

c. 1100 Gwynedd, Wales? |

| Died | 23 or 28 November 1170 (aged 69–70) |

| Burial | Bangor Cathedral |

Owain ap Gruffudd (c. 1100 – 23 or 28 November 1170) was King of Gwynedd, north Wales, from 1137 until his death in 1170, succeeding his father Gruffudd ap Cynan. He was called "Owain the Great" (Welsh: Owain Fawr) [1] and the first to be styled "Prince of Wales".[2] He is considered to be the most successful of all the North Welsh princes prior to his grandson, Llywelyn the Great. He became known as Owain Gwynedd (Middle Welsh: Owain Gwyned, "Owain of Gwynedd") to distinguish him from the contemporary king of southern Powys, Owain ap Gruffydd ap Maredudd, who became known as "Owain Cyfeiliog".[3]

Early life

Gwynedd was a member of the House of Aberffraw, the senior branch of the dynasty of Rhodri the Great. His father, Gruffudd ap Cynan, was a strong and long-lived ruler who had made the principality of Gwynedd the most influential in Wales during the sixty-two years of his reign, using the island of Anglesey as his power base. His mother, Angharad ferch Owain, was the daughter of Owain ab Edwin of Tegeingl. Gwynedd was the first son of Gruffydd and Angharad.

Owain is thought to have been born on Anglesey about the year 1100. By about 1120 Gruffydd had grown too old to lead his forces in battle and Owain and his brothers Cadwallon and later Cadwaladr led the forces of Gwynedd against the Normans and against other Welsh princes with great success. His elder brother Cadwallon was killed in a battle against the forces of Powys in 1132, leaving Owain as his father's heir. Owain and Cadwaladr, in alliance with Gruffydd ap Rhys of Deheubarth, won a major victory over the Normans at Crug Mawr near Cardigan in 1136 and annexed Ceredigion to their father's realm.

Accession to the throne and early campaigns

On Gruffydd's death in 1137, therefore, Owain inherited a portion of a well-established kingdom, but had to share it with Cadwaladr. In 1143 Cadwaladr was implicated in the murder of Anarawd ap Gruffydd of Deheubarth, and Owain responded by sending his son Hywel ab Owain Gwynedd to strip him of his lands in the north of Ceredigion. Though Owain was later reconciled with Cadwaladr, from 1143, Owain ruled alone over most of north Wales. In 1155 Cadwaladr was driven into exile.

Owain took advantage of the civil war in England between King Stephen and the Empress Matilda to push Gwynedd's boundaries further east than ever before.[4] In 1146 he captured the castle of Mold and about 1150 captured Rhuddlan and encroached on the borders of Powys. The prince of Powys, Madog ap Maredudd, with assistance from Earl Ranulf of Chester, gave battle at Coleshill, but Owain was victorious.

War with King Henry II

All went well until the accession of King Henry II of England in 1154. Henry invaded Gwynedd in 1157 with the support of Madog ap Maredudd of Powys and Owain's brother Cadwaladr. The invasion met with mixed fortunes. Henry's forces ravaged eastern Gwynedd and destroyed many churches thus enraging the local population. The two armies met at Ewloe. Owain's men ambushed the royal army in a narrow, wooded valley, routing it completely with King Henry himself narrowly avoiding capture.[5] The fleet accompanying the invasion made a landing on Anglesey where it was defeated. Ultimately, at the end of the campaign, Owain was forced to come to terms with Henry, being obliged to surrender Rhuddlan and other conquests in the east.

Forty years after these events, the scholar, Gerald of Wales, in a rare quote from these times, wrote what Owain Gwynedd said to his troops on the eve of battle:

"My opinion, indeed, by no means agrees with yours, for we ought to rejoice at this conduct of our adversary; for, unless supported by divine assistance, we are far inferior to the English; and they, by their behaviour, have made God their enemy, who is able most powerfully to avenge both himself and us. We therefore most devoutly promise God that we will henceforth pay greater reverence than ever to churches and holy places."[5]

Madog ap Maredudd died in 1160, enabling Owain to regain territory in the east. In 1163 he formed an alliance with Rhys ap Gruffydd of Deheubarth to challenge English rule. King Henry again invaded Gwynedd in 1165, but instead of taking the usual route along the northern coastal plain, the king's army invaded from Oswestry and took a route over the Berwyn hills. The invasion was met by an alliance of all the Welsh princes, with Owain as the undisputed leader. However, apart from a small melee at the Battle of Crogen there was little fighting, for the Welsh weather came to Owain's assistance as torrential rain forced Henry to retreat in disorder. The infuriated Henry mutilated a number of Welsh hostages, including two of Owain's sons.

Henry did not invade Gwynedd again and Owain was able to regain his eastern conquests, recapturing Rhuddlan castle in 1167 after a siege of three months.

Disputes with the church and succession

The last years of Owain's life were spent in disputes with the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket, over the appointment of a new Bishop of Bangor. When the see became vacant Owain had his nominee, Arthur of Bardsey, elected. The archbishop refused to accept this, so Owain had Arthur consecrated in Ireland. The dispute continued, and the see remained officially vacant until well after Owain's death. He was also put under pressure by the Archbishop and the Pope to put aside his second wife, Cristin, who was his first cousin, this relationship making the marriage invalid under church law. Despite being excommunicated for his defiance, Owain steadfastly refused to put Cristin aside. Owain died in 1169, and despite having been excommunicated was buried in Bangor Cathedral by the local clergy. The annalist writing Brut y Tywysogion recorded his death "after innumerable victories, and unconquered from his youth".

He is believed to have commissioned the propaganda text, The Life of Gruffydd ap Cynan, an account of his father's life. Following his death, civil war broke out between his sons. Owain was married twice, first to Gwladus ferch Llywarch ap Trahaearn, by whom he had two sons, Maelgwn ab Owain Gwynedd and Iorwerth Drwyndwn, the father of Llywelyn the Great, then to Cristin, by whom he had three sons including Dafydd ab Owain Gwynedd and Rhodri ab Owain Gwynedd. He also had a number of illegitimate sons, who by Welsh law had an equal claim on the inheritance if acknowledged by their father.

Heirs and successors

Owain had originally designated Rhun ab Owain Gwynedd as his successor. Rhun was Owain's favourite son, and his premature death in 1147 plunged his father into a deep melancholy, from which he was only roused by the news that his forces had captured Mold castle. Owain then designated Hywel ab Owain Gwynedd as his successor, but after his death Hywel was first driven to seek refuge in Ireland by Cristina's sons, Dafydd and Rhodri, then killed at the battle of Pentraeth when he returned with an Irish army. Dafydd and Rhodri split Gwynedd between them, but a generation passed before Gwynedd was restored to its former glory under Owain's grandson Llywelyn the Great.

According to legend, one of Owain's sons was Prince Madoc, who is popularly supposed to have fled across the Atlantic and colonised America.

Altogether, the prolific Owain Gwynedd is said to have had the following children from two wives and at least four mistresses:

- Rhun ab Owain Gwynedd (illegitimate in Catholic custom, but legitimate successor in Welsh law)

- Hywel ab Owain Gwynedd (illegitimate in Catholic custom, but legitimate successor in Welsh law)

- Iorwerth ab Owain Gwynedd (the "flat nose", also called Edward in some sources, from first wife Gwladys (Gladys) ferch Llywarch)

- Maelgwn ab Owain Gwynedd,(from first wife Gwladys (Gladys) ferch Llywarch) Lord of Môn (1169–1173)

- Gwenllian ferch Owain Gwynedd

- Dafydd ab Owain Gwynedd (from second wife Cristina (Christina) ferch Gronw)

- Rhodri ab Owain Gwynedd, Lord of Môn (1175–1193)

- Angharad ferch Owain Gwynedd

- Margaret ferch Owain Gwynedd

- Iefan ab Owain Gwynedd

- Cynan ab Owain Gwynedd, Lord of Meirionnydd (illegitimate)

- Rhirid ab Owain Gwynedd (illegitimate)

- Madoc ab Owain Gwynedd (illegitimate) (speculative/legendary)

- Cynwrig ab Owain Gwynedd (illegitimate)

- Gwenllian II ferch Owain Gwynedd (also shared the same name with a sister)

- Einion ab Owain Gwynedd (illegitimate)

- Iago ab Owain Gwynedd (illegitimate)

- Ffilip ab Owain Gwynedd (illegitimate)

- Cadell ab Owain Gwynedd (illegitimate)

- Rotpert ab Owain Gwynedd (illegitimate)

- Idwal ab Owain Gwynedd (illegitimate)

- Other daughters

Ancestry

| 16. Idwal ap Meurig ap Idwal Foel | ||||||||||||||||

| 8. Iago ab Idwal ap Meurig | ||||||||||||||||

| 4. Cynan ab Iago | ||||||||||||||||

| 2. Gruffudd ap Cynan | ||||||||||||||||

| 20. Sigtrygg Silkbeard | ||||||||||||||||

| 10. Amlaíb mac Sitriuc | ||||||||||||||||

| 21. Sláine daughter of Brian Boru | ||||||||||||||||

| 5. Ragnhilda of Ireland | ||||||||||||||||

| 1. Owain Gwynedd | ||||||||||||||||

| 24. Einion ab Owain | ||||||||||||||||

| 12. Edwin ab Einion | ||||||||||||||||

| 6. Owain ab Edwin | ||||||||||||||||

| 3. Angharad ferch Owain | ||||||||||||||||

Fiction

Owain is a recurring character in the Brother Cadfael series of novels by Ellis Peters, often referred to, and appearing in the novels Dead Man's Ransom and The Summer of the Danes. He acts shrewdly to keep Wales's borders secure, and sometimes to expand them, during the civil war between King Stephen and Matilda, and sometimes acts as an ally to Cadfael and his friend, Sheriff Hugh Beringar. Cadwaladr also appears in both these novels as a source of grief for his brother. Owain appears as a minor character in novels of Sharon Kay Penman concerning Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine ("When Christ and His Saints Slept" and "Time and Chance"). Her focus with respect to Owain is on the fluctuating and factious relationship between England and Wales.

He also appears in the Sarah Woodbury 'Gareth and Gwen Medieval Mystery Series' of books.

Titles

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Gruffudd ap Cynan |

Prince of Gwynedd 1137–1169 |

Succeeded by Hywel ab Owain Gwynedd |

References

- ↑ Lloyd 2004, p. 94.

- ↑ Davies, John; Jenkins, Nigel; Baines, Menna; Lynch, Peredur I., eds. (2008). The Welsh Academy Encyclopaedia of Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. p. 636. ISBN 978-0-7083-1953-6.

- ↑ Lloyd 2004, p. 93.

- ↑ R. R. Davies, Conquest, Coexistence and Change. Wales 1063-1415 (Oxford, 1987), p. 229.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Gerald of Wales, Itinirum Cambrae". Buildinghistory.org. 2010-03-16. Retrieved 2013-03-01.

Sources

- Lloyd, John Edward (2004). A History of Wales: From the Norman Invasion to the Edwardian Conquest. Banes & Noble. ISBN 978-0-7607-5241-8.