Overpopulation

Overpopulation occurs when a population of a species exceeds the carrying capacity of its ecological niche. Overpopulation is a function of the number of individuals compared to the relevant resources, such as the water and essential nutrients they need to survive. It can result from an increase in births, a decline in mortality rates, an increase in immigration, or an unsustainable biome and depletion of resources. [1]

Animal overpopulation

In the wilderness, the problem of overpopulation of species is often solved by growth in the population of predators. Predators tend to look for signs of weakness in their prey, and therefore usually first eat the old or sick animals. This has the side effects of controlling the prey population and ensuring its evolution in favor of genetic characteristics that enhance escape from predation (and the predator may co-evolve, in response).[2]

In the absence of predators, species are bound by the resources they can find in their environment, but this does not necessarily control overpopulation, at least in the short term. An abundant supply of resources can produce a population boom that ends up with more individuals than the environment can support. In this case, starvation, thirst and sometimes violent competition for scarce resources may affect a sharp reduction in population in a very short lapse (a population crash). Lemmings, as well as other species of rodents, are known to have such cycles of rapid population growth and subsequent decrease.

Some species seem to have a measure of self-control, by which individuals refrain from mating when they find themselves in a crowded environment. This voluntary abstinence may be induced by stress or by pheromones.

In an ideal setting, when animal populations grow, so do the number of predators that feed on that particular animal. Animals that have birth defects or weak genes (such as the runt of the litter) are unable to compete over food with stronger, healthier animals.

In reality, an animal that is not native to an environment may have advantages over the native ones, such being unsuitable for the local predators. If left uncontrolled, such an animal can quickly overpopulate and ultimately destroy its environment.

Examples

Examples of overpopulation caused by introduction of a foreign species abound:

- In the Argentine Patagonia, for example, European species such as the trout and the deer were introduced into the local streams and forests, respectively, and quickly became a plague, competing with and sometimes driving away the local species of fish and ruminants.[3]

- In Australia, when rabbits were introduced by European immigrants, they bred out of control and ate the farm crops and food that both native and farm animals needed. Farmers hunted the rabbits, and also brought cats in to guard against rabbits and rats. These introduced cats created another problem, becoming predators of local species.[4]

Examples of overpopulation caused by natural cyclic variations include:

- the 2004 Locust Outbreak in West and North Africa.

- the Australian locust plagues.

- Palestine's eight-month-long 1915 locust plague.

Human overpopulation

The human population has been growing continuously since the end of the Black Death, around the year 1400, although the most significant increase has been in the last 50 years, mainly due to medical advancements, increases in agricultural productivity and the historically-unique availability of abundant cheap energy. The rate of population growth has been declining since the 1980s. Most contemporary estimates for the carrying capacity of the Earth under existing conditions are between 4 billion and 16 billion. In 2013 the human population was 7 billion. By 2025 the world population is expected to grow by an additional 1 billion.[5] Depending on which estimate of overpopulation is used, human overpopulation may or may not have already occurred.

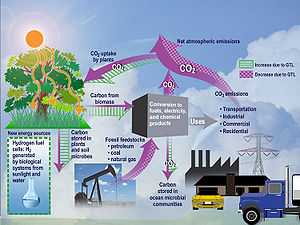

The InterAcademy Panel Statement on Population Growth, circa 1994, has stated that many environmental problems, such as rising levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide, global warming, and pollution, are aggravated by the population expansion.[6] Other problems associated with overpopulation include the increased demand for resources such as fresh water and food, starvation and malnutrition, consumption of natural resources (such as fossil fuels) faster than the rate of regeneration, and a deterioration in living conditions.[7] However, some believe that waste and over-consumption, especially by wealthy nations, is putting more strain on the environment than overpopulation.[8]

Overpopulation in domestic animals

Ethical issues of humaneness arise also from the unintended population growth of dogs, cats, and other domestic animals. Outcomes include euthanization of former pets and release of former pets to the wild.

See also

- Animal population control

- Culling

- Cascade effect

- Overexploitation

References

- ↑ "Dhirubhai Ambani International Model United Nations 2013" (PDF). Daimun. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ↑ Scott, Joe. "Predators and their prey - why we need them both". Conservation Northwest. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ↑ Speziale, Karina; Sergio, Lambertucci; Jose´, Tella; Martina, Carrete. "Dealing with Non-native Species: what makes the Difference in South America?" (PDF). Digital.CSIC Open Science. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ↑ Zukerman, Wendy (2009). "Australia's Battle with the Bunny". ABC Science.

- ↑ "What’s Next for Our Increasingly Overpopulated World?". Norwich University. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ↑ Joint statement by fifty-eight of the world's scientific academies. interacademies.net

- ↑ Zinkina J., Korotayev A. Explosive Population Growth in Tropical Africa: Crucial Omission in Development Forecasts (Emerging Risks and Way Out). World Futures 70/2 (2014): 120–139.

- ↑ Fred Pearce (2009-04-13). "Consumption Dwarfs Population as Main Environmental Threat". Yale University. Retrieved 2012-11-12.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||