Outlaw

In historical legal systems, an outlaw is declared as outside the protection of the law. In pre-modern societies, the criminal is withdrawn all legal protection, so that anyone is legally empowered to persecute or kill them. Outlawry was thus one of the harshest penalties in the legal system. In early Germanic law, the death penalty is conspicuously absent, and outlawing is the most extreme punishment, presumably amounting to a death sentence in practice. The concept is known from Roman law, as the status of homo sacer, and persisted throughout the Middle Ages.

In the common law of England, a "Writ of Outlawry" made the pronouncement Caput gerat lupinum ("Let his be a wolf's head", literally "May he bear a wolfish head") with respect to its subject, using "head" to refer to the entire person (cf. "per capita") and equating that person with a wolf in the eyes of the law: Not only was the subject deprived of all legal rights of the law being outside of the "law", but others could kill him on sight as if he were a wolf or other wild animal. Women were declared "waived" rather than outlawed but it was effectively the same punishment.[1]

Legal history

Ancient Rome

Among other forms of exile, Roman law included the penalty of interdicere aquae et ignis ("to forbid fire and water"). People so penalized were required to leave Roman territory and forfeit their property. If they returned, they were effectively outlaws; providing them the use of fire or water was illegal, and they could be killed at will without legal penalty.[2]

Interdicere aquae et ignis was traditionally imposed by the tribune of the plebs, and is attested to have been in use during the First Punic War of the third century BCE by Cato the Elder.[3] It was later also applied by many other officials, such as the Senate, magistrates,[2] and Julius Caesar as a general and provincial governor during the Gallic Wars.[4] It fell out of use during the early Empire.[2]

In England

In English common law, an outlaw was a person who had defied the laws of the realm, by such acts as ignoring a summons to court, or fleeing instead of appearing to plead when charged with a crime.[1] In the earlier law of Anglo-Saxon England, outlawry was also declared when a person committed a homicide and could not pay the weregild, the blood-money, that was due to the victim's kin.

Outlawry was a principally pre-Magna Carta phenomenon. It was by virtue of Magna Carta that the legal precepts due process and habeas corpus were concurrently established in 1214 thus commencing with their eventual enshrinement in judicial procedures, which required that persons suspected of crimes are required to be judged in a court of law before punishment can be legally rendered. The most famous English outlaw was Robin Hood, even if his historical existence is not proved.

Criminal

The term outlawry referred to the formal procedure of declaring someone an outlaw, i.e. putting him outside of the sphere of legal protection.[1] In the common law of England, a judgment of (criminal) outlawry was one of the harshest penalties in the legal system, since the outlaw could not use the legal system for protection, e.g. from mob justice. To be declared an outlaw was to suffer a form of civil or social[5] death. The outlaw was debarred from all civilized society. No one was allowed to give him food, shelter, or any other sort of support – to do so was to commit the crime of aiding and abetting, and to be in danger of the ban oneself. In effect, (criminal) outlaws were criminals on the run who were "wanted dead or alive".

An outlaw might be killed with impunity; and it was not only lawful but meritorious to kill a thief flying from justice — to do so was not murder. A man who slew a thief was expected to declare the fact without delay, otherwise the dead man’s kindred might clear his name by their oath and require the slayer to pay weregild as for a true man.[6]

By the rules of common law, a criminal outlaw did not need to be guilty of the crime he was outlawed for. If a man was accused of a treason or felony and, instead of appearing in court and defending himself from accusations, fled from justice, he was deemed to be convicted of the offence he had been accused of.[7] If he was accused of a misdemeanour, then he was guilty of a serious contempt of court which was itself a capital crime.

In the context of criminal law, outlawry faded not so much by legal changes as by the greater population density of the country, which made it harder for wanted fugitives to evade capture; and by the international adoption of extradition pacts. It was obsolete by the time it was abolished in 1938.[8][9][10]

Civil

There was also civil outlawry. Civil outlawry did not carry capital punishment with it, and it was imposed on defendants who fled or evaded justice when sued for civil actions like debts or torts. The punishments for civil outlawry were nevertheless harsh, including confiscation of chattels (movable property) left behind by the outlaw.[11]

In the civil context, outlawry became obsolescent in civil procedure by reforms that no longer required summoned defendants to appear and plead. Still, the possibility of being declared an outlaw for derelictions of civil duty continued to exist in English law until 1879 and in Scots law until the late 1940s. Since then, failure to find the defendant and serve process is usually interpreted in favour of the defendant, and harsh penalties for mere nonappearance (merely presumed flight to escape justice) no longer apply.

In other countries

Outlawry also existed in other ancient legal codes, such as the ancient Norse and Icelandic legal code. These societies did not have any police force or prisons and criminal sentences were therefore restricted to either fines or outlawry.

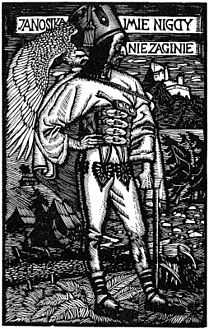

In early modern times, the term Vogelfrei and its cognates came to be used in Germany, the Low Countries and Scandinavia, referring to a person stripped of his civil rights being "free" for the taking like a bird.[12] In Germany and Slavic countries in 15th- 19th centuries groups of outlaws composed from former prisoners, soldiers etc. became an important social phenomenon. They lived from robbery and their activity was often supported by local inhabitants from lower classes (as a form of a social people resistance against oppressive political and economic systems). The best known are Juraj Jánošík and Jakub Surovec in Slovakia, Oleksa Dovbush in Ukraine, Rózsa Sándor in Hungary, Schinderhannes and Hans Kohlhase in Germany etc.

The concept of outlawry was reintroduced to British law by several Australian colonial governments in the late 19th century to deal with the menace of bushranging. The Felons Apprehension Act (1865)[13] of New South Wales provided that a judge could, upon proof of sufficiently notorious conduct, issue a special bench warrant requiring a person to submit themselves to police custody before a given date, or be declared an outlaw. An outlawed person could be apprehended "alive or dead" by any of the Queen's subjects, "whether a constable or not", and without "being accountable for using of any deadly weapon in aid of such apprehension." Similar provisions were passed in Victoria and Queensland.[14] Although the provisions of the New South Wales Felons Apprehension Act were not exercised after the end of the bushranging era, they remained on the statute book until 1976.[15]

The Third Reich made extensive use of outlawry in the persecution of Jews or other persons deemed undesirable to the state.[16]

In post-World War II Europe, prior to the Nuremberg Trials, the British jurist and Lord Chancellor Lord Simon attempted to resurrect the concept of outlawry in order to provide for summary executions of captured Nazi war criminals. Although Simon's point of view was supported by Churchill, American and Soviet attorneys insisted on a trial in each case, and Simon was thus overruled.

Outlawing as political weapon

There have been many instances in military and/or political conflicts throughout History whereby one side declares the other as being "illegal", notorious cases being the use of Proscription in Republican Rome's civil wars. In later times there was the notable case of Napoleon Bonaparte whom the Congress of Vienna, in 13 March 1815, declared to be "outside the law".[17]

In modern times, the government of the First Spanish Republic, unable to reduce the Cantonalist rebellion centered in Cartagena, Spain, declared the Cartagena fleet to be "piratic", which allowed any nation to prey on it.

Taking the opposite road, some outlaws became political leaders, such as Ethiopia's Kassa Hailu who became Emperor Tewodros II of Ethiopia.

Popular usage

Though the judgment of outlawry is now obsolete (even though it inspired the pro forma Outlawries Bill which is still to this day introduced in the British House of Commons during the State Opening of Parliament), romanticised outlaws became stock characters in several fictional settings. This was particularly so in the United States, where outlaws were popular subjects of newspaper coverage and stories in the 19th century, and 20th century fiction and Western movies. Thus, "outlaw" is still commonly used to mean those violating the law[18] or, by extension, those living that lifestyle, whether actual criminals evading the law or those merely opposed to "law-and-order" notions of conformity and authority (such as the "outlaw country" music movement in the 1970s).

See also

|

|

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 National Archives staff (26 January 2012). "The outlaw in medieval and early modern England". British National Archives. Retrieved June 2012. Check date values in:

|year= / |date= mismatch(help) - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Berger, p. 507.

- ↑ Kelly 2006, p. 28.

- ↑ Caesar, Julius. De Bello Gallico, book VI, section XLIV.

- ↑ Bauman, Zygmunt (n.d.). Modernity and Holocaust. p. .

- ↑ Pollock & Maitland 1968, p. 53.

- ↑ Archbold Criminal Pleading, Evidence and Practice (30th ed., 1938) page 71

- ↑ Archbold (30th ed., 1938) page 71

- ↑ Archbold (31st ed., 1943) page 98

- ↑ Administration of Justice (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1938, section 12

- ↑ William Blackstone (1753), Commentaries on the Laws of England, Book 3, Chapter XIX "Of Process"

- ↑ Schmidt–Wiegand, Ruth (1998). "Vogelfrei". Handwörterbuch der Deutschen Rechtsgeschichte [Dictionary of the History of German Law]. 5: Straftheorie [Penal theory]. Berlin: Schmidt. pp. 930–932. ISBN 3-503-00015-1

- ↑ New South Wales government website. "Text of the Felons Apprehension Act (1865)" (PDF). Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ↑ ANZLH E-Journal. "Outlawry in Colonial Australia: The Felons Apprehension Acts 1865-1899" (PDF). Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ↑ ANZLH E-Journal. "Outlawry in Colonial Australia: The Felons Apprehension Acts 1865-1899" (PDF). Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ↑ Shirer, William L. (2011). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany. pp. 233, 439.

- ↑ Timeline: The Congress of Vienna, the Hundred Days, and Napoleon's Exile on St Helena, Center of Digital Initiatives, Brown University Library

- ↑ Black's Law Dictionary at 1255 (4th ed. 1951), citing Oliveros v. Henderson, 116 S.C. 77, 106 S.E. 855, 859.

References

- Berger, Adolf. "Interdicere aqua et igni". Encyclopedic Dictionary of Roman Law. p. 507.

- Kelly, Gordon P. (2006). A history of exile in the Roman republic. Cambridge University Press. p. 28.

- McLoughlin, Denis (1977). The Encyclopedia of the Old West. Taylor & Francisb. ISBN 9780710009630.

- Pollock, F.; Maitland, F. W. (1968) [1895]. The History of English Law Before the Time of Edward I (2nd (1898), reprint ed.). Cambridge.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||